Lepidurus apus

| Lepidurus apus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Division: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Branchiopoda |

| Order: | Notostraca |

| Family: | Triopsidae |

| Genus: | Lepidurus |

| Species: | L. apus |

| Binomial name | |

| Lepidurus apus (Linnaeus, 1758) | |

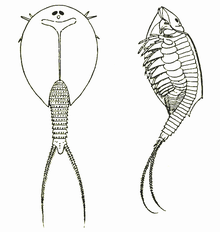

Lepidurus apus, commonly known as tadpole shrimp and belongs to the family triopsidae, which are a lineage of shrimps that have been around in a similar form since the Triassic period and are considered living fossils, and are found in several countries spread throughout the world. They have a long segmented abdomen with a carapace and large numbers of paddle like legs for movement. The species reproduces by a mixture of sexual reproduction and self-fertilisation of females.

Description

Lepidurus apus are known to grow from 42mm-60mm in length and have a long multi segmented abdomen divided up into around 30 ring like sections, with two caudal filaments attached behind the last ring.[1] They have a single pair of compound eyes, a flat carapace with an average length of 19mm that covers up to two thirds of the abdomen that is a mottled dark yellow/brown colour that transitions to a lighter edge. It wraps around most of its body attached only at the front, with its abdomen being multi-segmented with two long protruding tails.[2] At the front of the abdomen are one or more (up to three) sets of feelers. On the bottom of the body are between 41-46 sets of paddle like limbs they use to swim with an average of 44 leg pairs.[3] Males are readily identifiable by the lack of ovisacs found as well as subtle differences in it carapace. Females and hermaphrodites are virtually the same in appearance however the presence of testicular lobes in amongst the ovarian lobes in the hermaphrodites allows them to reproduce in isolation.

Distribution

Natural global range

Lepidurus apus is perhaps the most widespread of all Nostrocata species occurring in several widespread countries including but not limited to New Zealand, Australia, Iran, France, Germany, Italy,[4] Denmark,[5] Morocco[6] and Austria. However Lepidurus apus is split into several sub-species based on slight differences due to geographic dispersion, such as Lepidurus apus viridis the Australasian variant present in parts of Australia, Tasmania and New Zealand.[7]

New Zealand range

Lepidurus apus viridis is not a well-studied or common species in New Zealand with no exact report on its distribution, however Department of Conservation reports it as scattered throughout New Zealand in small ponds and ditches.[7] In 2006 Lepidurus apus was found in Marlborough in a shallow pool near Seddon.

Habitat preferences

Lepidurus apus viridis is found predominantly in temporary freshwater pond and is known to be found in permanent water bodies such as swamps, ditches and ponds but in lesser numbers than in temporary locations due to its life-cycle allowing it to become dormant in areas not suited to its survival. These ponds range in depth of 10–100 cm. These are often filled during autumn and winter, and dry out over spring and summer. The species also can be found in the dry sediment margins of ditches as a cyst form which can survive harsh conditions for many years until they find suitable conditions.[6] Seasonal ponds can be frozen over and covered with snow or dried out and the cysts can still survive, making this species one of the best surviving species in terms of adaptation to variations of climate and location. Due to the increasing modification of wetlands and temporary ponds to grasslands for predominately agriculture, the total land area available for the species is gradually diminishing and certain subspecies such as Lepidurus apus viridis may become threatened in future, or are already under threat, due to the localised nature and limited knowledge of some subspecies.[7][8] Thought to be threatened worldwide due to the decline in habitat, although Lepidurus apus appears to be least sensitive to human pressures across geographical ranges perhaps due to its easily dispersal and highly resilient eggs. Although we cannot confer that this is optimum habitat level for Lepidurus apus we know that the species can tolerate relatively high concentrations of chemicals, as studies found pools Lepidurus apus was living in had levels of total nitrate of 1 mg/L and total phosphate of 0.1 mg/L which are relatively high concentrations and would affect other aquatic species.[1] "Lepidurus apps" prefer's shallow ponds with water depth varied from 0.10 to 0.25m, Ph values of the water were best between 6 and 7.8.

Life cycle/Phenology

Lepidurus apus has an unusual life-cycle in that it is able to produce microbial cysts that can lie dormant for years at a time through varying and extreme conditions that make it effective at surviving in several different areas with vastly different climates such as Morocco and Denmark. The "resting eggs" are so drought resistant, there is an example of a L. apus eggs hatching after being kept dry for 28 years. The species is hermaphroditic with no males are found in New Zealand in the subspecies viridius,[7] though this is not the case worldwide with populations in Italy that have males that are non functional. However some studies have described Lepidurus apus as bisexual.[9] Different subspecies of Lepidurus apus have different methods of fertilisation of the eggs, some by a male of the species, some by hermaphroditic individuals. Lepidurus apus inundation period often happens after rainfall in the cooler months that form temporal ponds.Lepidurus apus larvae feed and rapidly grow to maturity in the temporal pools. When Lepidurus apus lays its cysts, which have been found at concentrations of up to 250 per 100 cm squared,[6] with an average size 0.447 mm in diameter,[8] it tends to place them on gravel in the middle of ditches or ponds which is speculated to be with avoiding large animals such as sheep that will transport the cysts away from the safety of the wet ditch onto land.[6] These cysts can survive harsh conditions including drought and sub zero temperatures,[1] the cysts can also synthesise haemoglobin if there is a lack of oxygen.[7] As the pond dries out in the summer and warmer months, the eggs enter its drought resistance stage of its life cycle where the eggs will lay dormant until immersed in water. Tests done showed that light is an important factor in hatching of Lepidurus apus as no cysts hatched in darkness while some hatched after 10 mins of bright light and all hatched in continuous light.[8] These tests also showed that the optimum range for Lepidurus apus to hatch is between 16 °C and 20 °C though they hatched between 10 °C and 24 °C. When the conditions are right the cysts will break open and the offspring will reach maturity in as little as 4 weeks in optimum conditions in the warmer summer and spring months,[7] however tests by under perceived optimum conditions never got more than a 60% hatch rate.[8] However each individual produces a large number of cysts so the total number of offspring from each animal are high, meaning a high reproductive rate with very little parental input. Because Lepidurus apus has been found in remote geographically isolated areas with no water features to transport the species to areas like Iran it is concluded that migratory birds are a primary means of transport to new areas,[1] which also explains the global scale of Lepidurus apus. As their eggs are resilient to desiccation (a state of extreme dryness), in dry conditions, the resting eggs are also easily distributed in dust by wind, which could explain its wide distribution. Lepidurus apus eggs are also though to be distributed by water, people, wildlife and birds.

Diet and foraging

Lepidurus apus is omnivorous, feeding on both plant matter, mostly floating detritus, and small aquatic invertebrates.[3] A study in Utah analysed the stomach content of L.apus and found that’s as well as eating detritus they eat live Branchinecta and Daphinia making it a predator. L. apus Swims along the bottom of the pond stirring up the substrate foraging for food. As a genera Lepidurus feeds upon algae, myxozoa, bacteria and fungi so local species of such species would be included into the diet of Lepidurus Apus'.[2]

Predators, Parasites, and Diseases

Because Lepidurus apus and its subspecies encompass several countries and no complete study has been made on the genera and it's different geographically isolated populations there is no complete list of predators, but based on the predators of the Lepidurus genera, which include small wading birds such as the sandpiper or stint or larger waterfowl like geese, ducks and swans as well as small salmon in some ponds, it can be assumed that whatever species of fish, waterfowl or wading bird inhabits the area of Lepidurus apus is potentially a predator.[2] Migrating birds feed from these temporal pools as well as itinerant birds already found in the area. The rapid abundance of Lepidurus apus and other small invertebrates in temporal pools often results in an increase in bird numbers in the area.

There is one studied species which parasites on Lepidurus apus, Nosema lepiduri is a microsporidian parasite that affects Lepidurus found in water bodies less than 15 cm deep that internally parasites Lepidurus with spores, in some cases killing the hosts. The infected Lepidurus are able to be recognized by the milky white colouration on the legs and carapace due to the internal infection of Nosema lepiduri spores.[10]

Interesting Fact

L. apus was thought to be virtually unchanged for over 300 million years and they are often referred to as ‘living fossils’. However, a recent study suggests that though the present day L. apus does resemble that of a fossilised specimen possibly as old as 250 million years, there is no molecular support for this. It states it is probably a result of the ‘highly conserved general morphology in this group and of homoplasy’. This study has shown that recent species of L. apus are nearly identical to fossil records in terms of their morphology but may ‘represent very different evolutionary lineages’.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Behroz, Atashbar; Naser, Agh; Lynda, Beladjal; Johan, Mertens (2013). "on the occurrence of Lepidurus apus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Crustacea, notostraca) from Iran". Journal of Biological Research-Thessaloniki: 75–79.

- 1 2 3 "Lepidurus apus". Encyclopedia of Life.

- 1 2 "TADPOLE SHRIMPS ( TRIOPSIDAE : LEPIDURUS )". Landcare Research. 2015.

- ↑ Scanabissi, Franca; Mondini, Corrado (October 2002). "A survey of the reproductive biology in Italian branchiopods". Hydrobiologia 486 (1): 263–272. doi:10.1023/a:1021371306687.

- ↑ Damgaard, Jakob; Olesen, Jørgen (1998). "Distribution, phenology and status for the larger Branchiopoda (Crustacea: Anostraca, Notostraca, Spinicaudata and Laevicaudata) in Denmark". Hydrobiologia 337 (3): 9–13.

- 1 2 3 4 Thiéry, Alain (1997). "Horizontal distribution and abundance of cysts of several large branchiopods in temporary pool and ditch sediments". Hydrobiologia 359: 177–189.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Collier, Kevin (1992). "Freshwater Macroinvertebrates of potenital conservation interest". Department of Conservation. p. 24.

- 1 2 3 4 Kuller, Z; Gasith, A (1996). "Comparison of the hatching process of the tadpole shrimps Triops cancriformis and Lepidurus apus lubbocki (Notosraca) and its relation to their distribution in rain-pools in Israel". Hydrobiologica 335: 147–156. doi:10.1007/bf00015276.

- ↑ Scanabissi, Franca; Mondini, Corrado (October 2002). "A survey of the reproductive biology in Italian branchiopods". Hydrobiologia 486: 263–272. doi:10.1023/a:1021371306687.

- ↑ Vavra, Jiri (1960). "Nosema lepiduri n. sp., a New Microsporidian Parasite in Lepidurus apus". The Journal of Protozoology 7: 36–41. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1960.tb00704.x.