Leon Battista Alberti

| Leon Battista Alberti | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Leon Battista Alberti February 14, 1404 Genoa, Italy |

| Died |

April 25, 1472 (aged 68) Rome, Italy |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Known for | Architecture, Linguistics, Poetry |

| Notable work | Tempio Malatestiano, Palazzo Rucellai, Santa Maria Novella |

| Movement | Italian Renaissance |

Leon Battista Alberti (Italian pronunciation: [leˈom batˈtista alˈbɛrti]; February 14, 1404 – April 25, 1472) was an Italian humanist author, artist, architect, poet, priest, linguist, philosopher and cryptographer; he epitomised the Renaissance Man. Although he is often characterized as an "architect" exclusively, as James Beck has observed,[1] "to single out one of Leon Battista's 'fields' over others as somehow functionally independent and self-sufficient is of no help at all to any effort to characterize Alberti's extensive explorations in the fine arts." Alberti's life was described in Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects.

Life

Leon Battista Alberti was born in 1404 in Genoa to a wealthy Florentine father who had been exiled from his own city, but who was allowed to return in 1428. Alberti, whose mother is unknown, and who was probably illegitimate, was sent to boarding school in Padua, then studied Law at Bologna.[2] He lived for a time in Florence, then travelled to Rome in 1431, where he took holy orders and entered the service of the papal court.[3] At this time he studied the ancient ruins, which excited his interest in architecture and strongly influenced the form of the buildings that he designed.[3]

Alberti was gifted in many directions. He was tall, strong and a fine athlete, who could ride the wildest horse and jump over a man's head.[4] He distinguished himself as a writer while he was still a child at school, and by the age of twenty had written a play which was successfully passed off as a genuine piece of Classical literature.[2] In 1435, he began his first major written work, Della pittura, in which, inspired by the burgeoning of pictorial art in Florence in the early 15th century, he analyses the nature of painting and explores the elements of perspective, composition and colour.[3]

In 1438 he began to take a serious interest in architecture, encouraged by the Marchese Leonello d'Este of Ferrara, for whom he built a small triumphal arch to support an equestrian statue of Leonello's father.[2] In 1447 he became the architectural advisor to Pope Nicholas V and was involved with a number of projects at the Vatican.[2]

His first major architectural commission was in 1446 for the facade of the Rucellai Palace in Florence. This was followed in 1450 by a commission from Sigismondo Malatesta to transform the Gothic church of San Francesco in Rimini into a memorial chapel, the Tempio Malatestiano.[3] In Florence, he designed the upper parts of the facade for the Dominican church of Santa Maria Novella, famously bridging the nave and lower aisles with two ornately inlaid scrolls, solving a visual problem and setting a precedent to be followed by architects of churches for four hundred years.[5] In 1452, he completed De re aedificatoria, a treatise on architecture, using as its basis the work of Vitruvius and influenced by the archaeological remains of Rome. The work was not published until 1485. It was followed in 1464 by his less influential work, De statua, in which he examines sculpture.[3] Alberti's only known sculpture is a self-portrait medallion, sometimes attributed to Pisanello.

Alberti was employed to design two churches in Mantua, San Sebastiano, which was never completed, and for which Alberti's intention can only be speculated, and the Basilica of Sant'Andrea. The design for the latter church was completed in 1471, a year before Alberti's death, but was brought to completion and is his most significant work.[5]

As an artist, Alberti distinguished himself from the ordinary craftsman, educated in workshops. He was a humanist, and part of the rapidly expanding entourage of intellectuals and artisans supported by the courts of the princes and lords of the time. Alberti, as a member of noble family and as part of the Roman curia, had special status. He was a welcomed guest at the Este court in Ferrara, and in Urbino he spent part of the hot-weather season with the soldier-prince Federico III da Montefeltro. The Duke of Urbino was a shrewd military commander, who generously spent money on the patronage of art. Alberti planned to dedicate his treatise on architecture to his friend.[4]

Among Alberti's smaller studies, pioneering in their field, were a treatise in cryptography, De componendis cifris, and the first Italian grammar. With the Florentine cosmographer Paolo Toscanelli he collaborated in astronomy, a close science to geography at that time, and produced a small Latin work on geography, Descriptio urbis Romae (The Panorama of the City of Rome). Just a few years before his death, Alberti completed De iciarchia (On Ruling the Household), a dialogue about Florence during the Medici rule.

Alberti, having taken holy orders, remained unmarried all his life. He loved animals and had a pet dog, a mongrel, for whom he wrote a panegyric, Canis).[4] Vasari describes him as "an admirable citizen, a man of culture.... a friend of talented men, open and courteous with everyone. He always lived honourably and like the gentleman he was."[6] Alberti died in Rome on April 25, 1472 at the age of 68.

Publications

Alberti regarded mathematics as the common ground of art and the sciences. "To make clear my exposition in writing this brief commentary on painting," Alberti began his treatise, Della Pittura (On Painting), "I will take first from the mathematicians those things with which my subject is concerned."[7]

Della pittura (also known in Latin as De Pictura) relied in its scientific content on classical optics in determining perspective as a geometric instrument of artistic and architectural representation. Alberti was well-versed in the sciences of his age. His knowledge of optics was connected to the handed-down long-standing tradition of the Kitab al-manazir (The Optics; De aspectibus) of the Arab polymath Alhazen (Ibn al-Haytham, d. c. 1041), which was mediated by Franciscan optical workshops of the 13th-century Perspectivae traditions of scholars such as Roger Bacon, John Peckham and Witelo (similar influences are also traceable in the third commentary of Lorenzo Ghiberti, Commentario terzo).[8]

In both Della pittura and De statua, Alberti stressed that "all steps of learning should be sought from nature."[9] The ultimate aim of an artist is to imitate nature. Painters and sculptors strive "through by different skills, at the same goal, namely that as nearly as possible the work they have undertaken shall appear to the observer to be similar to the real objects of nature."[9] However, Alberti did not mean that artists should imitate nature objectively, as it is, but the artist should be especially attentive to beauty, "for in painting beauty is as pleasing as it is necessary."[9] The work of art is, according to Alberti, so constructed that it is impossible to take anything away from it or add anything to it, without impairing the beauty of the whole. Beauty was for Alberti "the harmony of all parts in relation to one another," and subsequently "this concord is realized in a particular number, proportion, and arrangement demanded by harmony." Alberti's thoughts on harmony were not new—they could be traced back to Pythagoras—but he set them in a fresh context, which fit in well with the contemporary aesthetic discourse.

In Rome, Alberti had plenty of time to study its ancient sites, ruins, and objects. His detailed observations, included in his De Re Aedificatoria (1452, On the Art of Building),[10] were patterned after the De architectura by the Roman architect and engineer Vitruvius (fl. 46–30 BC). The work was the first architectural treatise of the Renaissance. It covered a wide range of subjects, from history to town planning, and engineering to the philosophy of beauty. De re aedificatoria, a large and expensive book, was not fully published until 1485, after which it became a major reference for architects.[11] However, the book was written "not only for craftsmen but also for anyone interested in the noble arts," as Alberti put it.[10] Originally published in Latin, the first Italian edition came out in 1546. and the standard Italian edition by Cosimo Bartoli was published in 1550. Pope Nicholas V, to whom Alberti dedicated the whole work, dreamed of rebuilding the city of Rome, but he managed to realize only a fragment of his visionary plans. Through his book, Alberti opened up his theories and ideals of the Florentine Renaissance to architects, scholars and others.

Alberti wrote I Libri della famiglia—which discussed education, marriage, household management, and money—in the Tuscan dialect. The work was not printed until 1843. Like Erasmus decades later, Alberti stressed the need for a reform in education. He noted that "the care of very young children is women's work, for nurses or the mother," and that at the earliest possible age children should be taught the alphabet.[9] With great hopes, he gave the work to his family to read, but in his autobiography Alberti confesses that "he could hardly avoid feeling rage, moreover, when he saw some of his relatives openly ridiculing both the whole work and the author's futile enterprise along it."[9] Momus, written between 1443 and 1450, was a misogynist comedy about the Olympian gods. It has been considered as a roman à clef—Jupiter has been identified in some sources as Pope Eugenius IV and Pope Nicholas V. Alberti borrowed many of its characters from Lucian, one of his favorite Greek writers. The name of its hero, Momus, refers to the Greek word for blame or criticism. After being expelled from heaven, Momus, the god of mockery, is eventually castrated. Jupiter and the other gods come down to earth also, but they return to heaven after Jupiter breaks his nose in a great storm.

Architectural works

Alberti did not concern himself with the practicalities of building, and very few of his major works were brought to completion. As a designer and a student of Vitruvius and of ancient Roman remains, he grasped the nature of column and lintel architecture, from the visual rather than structural viewpoint, and correctly employed the Classical orders, unlike his contemporary, Brunelleschi, who utilised the Classical column and pilaster in a free interpretation. Among Alberti's concerns was the social effect of architecture, and to this end he was very well aware of the cityscape.[5] This is demonstrated by his inclusion, at the Rucellai Palace, of a continuous bench for seating at the level of the basement.

In Rome he was employed by Pope Nicholas V for the restoration of the Roman aqueduct of Acqua Vergine, which debouched into a simple basin designed by Alberti, which was swept away later by the Baroque Trevi Fountain.

Some studies[12] propose that the Villa Medici in Fiesole might owe its design to Alberti, not to Michelozzo, and that it then became the prototype of the Renaissance villa. This hilltop dwelling, commissioned by Giovanni de' Medici, Cosimo il Vecchio's second son, with its view over the city, may be the very first example of a Renaissance villa: that is to say it follows the Albertian criteria for rendering a country dwelling a "villa suburbana". Under this perspective the Villa Medici in Fiesole could therefore be considered the "muse" for numerous other buildings, not only in the Florence area, which from the end of the 15th century onwards find inspiration and creative innovation here.

Tempio Malatestiano, Rimini

The Tempio Malatestiano in Rimini (1447, 1453–60)[13] is the rebuilding of a Gothic church. The facade, with its dynamic play of forms, was left incomplete.[5]

Façade of Palazzo Rucellai

The design of the façade of the Palazzo Rucellai (1446–51) was one of several commissions for the Rucellai family.[13] The design overlays a grid of shallow pilasters and cornices in the Classical manner onto rusticated masonry, and is surmounted by a heavy cornice. The inner courtyard has Corinthian columns. The palace set a standard in the use of Classical elements that is original in civic buildings in Florence, and greatly influenced later palazzi. The work was executed by Bernardo Rosselino.[5]

Santa Maria Novella

At Santa Maria Novella, Florence, between (1448–70)[13] the upper facade was constructed to the design of Alberti. It was a challenging task, as the lower level already had three doorways and six Gothic niches containing tombs and employing the polychrome marble typical of Florentine churches such as San Miniato al Monte and the Baptistery of Florence. The design also incorporates an ocular window which was already in place. Alberti introduced Classical features around the portico and spread the polychromy over the entire facade in a manner which includes Classical proportions and elements such as pilasters, cornices and a pediment in the Classical style, ornamented with a sunburst in tesserae, rather than sculpture. The best known feature of this typically aisled church is the manner in which Alberti has solved the problem of visually bridging the different levels of the central nave and much lower side aisles. He employed two large scrolls, which were to become a standard feature of Church facades in the later Renaissance, Baroque and Classical Revival buildings.[5]

Pienza

Alberti is considered to have been the consultant for the design of the Piazza Pio II, Pienza. The village, previously called Corsignano, was redesigned beginning around 1459.[13] It was the birthplace of Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini, Pope Pius II, in whose employ Alberti served. Pius II wanted to use the village as a retreat but needed for it to reflect the dignity of his position.

The piazza is a trapezoid shape defined by four buildings, with a focus on Pienza Cathedral and passages on either side opening onto a landscape view. The principal residence, Palazzo Piccolomini, is on the west side. It has three stories, articulated by pilasters and entablature courses, with a twin-lighted cross window set within each bay. This structure is similar to Alberti's Palazzo Rucellai in Florence and other later palaces. Noteworthy is the internal court of the palazzo. The back of the palace, to the south, is defined by loggia on all three floors that overlook an enclosed Italian Renaissance garden with Giardino all'italiana era modifications, and spectacular views into the distant landscape of the Val d'Orcia and Pope Pius's beloved Mount Amiata beyond. Below this garden is a vaulted stable that had stalls for 100 horses. The design, which radically transformed the center of the town, included a palace for the pope, a church, a town hall and a building for the bishops who would accompany the Pope on his trips. Pienza is considered an early example of Renaissance urban planning.

Sant' Andrea, Mantua

The Basilica of Sant'Andrea, Mantua was begun in 1471,[13] the year before Alberti's death. It was brought to completion and is his most significant work employing the triumphal arch motif, both for its facade and interior, and influencing many works that were to follow.[5] Alberti perceived the role of architect as designer. Unlike Brunelleschi, he had no interest in the construction, leaving the practicalities to builders and the oversight to others.[5]

Other buildings

- San Sebastiano, Mantua, (begun 1458)[13] the unfinished facade of which has promoted much speculation as to Alberti's intention[5]

- Sepolcro Rucellai in San Pancrazio, 1467)[13]

- The Tribune for Santissima Annunziata, Florence (1470, completed with alterations, 1477)[13]

Painting

Giorgio Vasari, who argued that historical progress in art reached its peak in Michelangelo, emphasized Alberti's scholarly achievements, not his artistic talents: "He spent his time finding out about the world and studying the proportions of antiquities; but above all, following his natural genius, he concentrated on writing rather than on applied work." [6] Leonardo, who ironically called himself "an uneducated person" (omo senza lettere), followed Alberti in the view that painting is science. However, as a scientist Leonardo was more empirical than Alberti, who was a theorist and did not have similar interest in practice. Alberti believed in ideal beauty, but Leonardo filled his notebooks with observations on human proportions, page after page, ending with his famous drawing of the Vitruvian man, a human figure related to a square and a circle.

In On Painting, Alberti uses the expression "We Painters", but as a painter, or sculptor, he was a dilettante. "In painting Alberti achieved nothing of any great importance or beauty," wrote Vasari.[6] "The very few paintings of his that are extant are far from perfect, but this is not surprising since he devoted himself more to his studies than to draughtsmanship." Jacob Burckhardt portrayed Alberti in The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy as a truly universal genius. "And Leonardo Da Vinci was to Alberti as the finisher to the beginner, as the master to the dilettante. Would only that Vasari's work were here supplemented by a description like that of Alberti! The colossal outlines of Leonardo's nature can never be more than dimly and distantly conceived."[4]

Alberti is said to be in Mantegna's great frescoes in the Camera degli Sposi, the older man dressed in dark red clothes, who whispers in the ear of Ludovico Gonzaga, the ruler of Mantua. In Alberti's self-portrait, a large plaquette, he is clothed as a Roman. To the left of his profile is a winged eye. On the reverse side is the question, Quid tum? (what then), taken from Virgil's Eclogues: "So what, if Amyntas is dark? (quid tum si fuscus Amyntas?) Violets are black, and hyacinths are black."

Contributions

Alberti made a variety of contributions to several fields:

- Alberti was the creator of a theory called "historia". In his treatise De pictura (1435) he explains the theory of the accumulation of people, animals, and buildings, which create harmony amongst each other, and "hold the eye of the learned and unlearned spectator for a long while with a certain sense of pleasure and emotion". De pictura ("On Painting") contained the first scientific study of perspective. An Italian translation of De pictura (Della pittura) was published in 1436, one year after the original Latin version and addressed Filippo Brunelleschi in the preface. The Latin version had been dedicated to Alberti's humanist patron, Gianfrancesco Gonzaga of Mantua. He also wrote works on [sculpture], De Statua.

- Alberti used his artistic treatises to propound a new humanistic theory of art. He drew on his contacts with early Quattrocento artists such as Brunelleschi, Donatello and Ghiberti to provide a practical handbook for the renaissance artist.

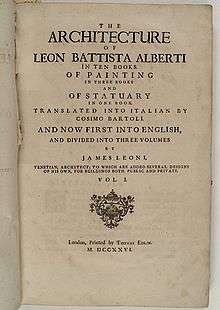

- Alberti wrote an influential work on architecture, De Re Aedificatoria, which by the 16th century had been translated into Italian (by Cosimo Bartoli), French, Spanish and English. An English translation was by Giacomo Leoni in the early 18th century. Newer translations are now available.

- Whilst Alberti's treatises on painting and architecture have been hailed as the founding texts of a new form of art, breaking from the Gothic past, it is impossible to know the extent of their practical impact within his lifetime. His praise of the Calumny of Apelles led to several attempts to emulate it, including paintings by Botticelli and Signorelli. His stylistic ideals have been put into practice in the works of Mantegna, Piero della Francesca and Fra Angelico. But how far Alberti was responsible for these innovations and how far he was simply articulating the trends of the artistic movement, with which his practical experience had made him familiar, is impossible to ascertain.

- He was so skilled in Latin verse that a comedy he wrote in his twentieth year, entitled Philodoxius, would later deceive the younger Aldus Manutius, who edited and published it as the genuine work of 'Lepidus Comicus'.

_-_0851.jpg)

- He has been credited with being the author, or alternatively the designer of the woodcut illustrations, of the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, a strange fantasy novel.[14]

- Apart from his treatises on the arts, Alberti also wrote: Philodoxus ("Lover of Glory", 1424), De commodis litterarum atque incommodis ("On the Advantages and Disadvantages of Literary Studies", 1429), Intercoenales ("Table Talk", c. 1429), Della famiglia ("On the Family", begun 1432) Vita S. Potiti ("Life of St. Potitus", 1433), De iure (On Law, 1437), Theogenius ("The Origin of the Gods", c. 1440), Profugorium ab aerumna ("Refuge from Mental Anguish",), Momus (1450) and De Iciarchia ("On the Prince", 1468). These and other works were translated and printed in Venice by the humanist Cosimo Bartoli in 1586.

- Alberti was an accomplished cryptographer by the standard of his day, and invented the first polyalphabetic cipher, which is now known as the Alberti cipher, and machine-assisted encryption using his Cipher Disk. The polyalphabetic cipher was, at least in principle, for it was not properly used for several hundred years, the most significant advance in cryptography since before Julius Caesar's time. Cryptography historian David Kahn titles him the "Father of Western Cryptography", pointing to three significant advances in the field which can be attributed to Alberti: "the earliest Western exposition of cryptanalysis, the invention of polyalphabetic substitution, and the invention of enciphered code."David Kahn (1967). The codebreakers: the story of secret writing. New York: MacMillan.

- According to Alberti himself, in a short autobiography written c. 1438 in Latin and in the third person, (many but not all scholars consider this work to be an autobiography) he was capable of "standing with his feet together, and springing over a man's head." The autobiography survives thanks to an 18th-century transcription by Antonio Muratori. Alberti also claimed that he "excelled in all bodily exercises; could, with feet tied, leap over a standing man; could in the great cathedral, throw a coin far up to ring against the vault; amused himself by taming wild horses and climbing mountains." Needless to say, many in the Renaissance promoted themselves in various ways and Alberti's eagerness to promote his skills should be understood, to some extent, within that framework. (This advice should be followed in reading the above information, some of which originates in this so-called autobiography.)

- Alberti claimed in his "autobiography" to be an accomplished musician and organist, but there is no hard evidence to support this claim. In fact, musical posers were not uncommon in his day (see the lyrics to the song Musica Son, by Francesco Landini, for complaints to this effect.) He held the appointment of canon in the metropolitan church of Florence, and thus – perhaps – had the leisure to devote himself to this art, but this is only speculation. Vasari also agreed with this.[6]

- He was also interested in the drawing of maps and worked with the astronomer, astrologer, and cartographer Paolo Toscanelli.

- In terms of Aesthetics Alberti is one of the first defining the work of art as imitation of nature, exactly as a selection of its most beautiful parts: "So let's take from nature what we are going to paint, and from nature we choose the most beautiful and worthy things"[15]

Works in print

- De Pictura, 1435. On Painting, in English, De Pictura, in Latin, On Painting. Penguin Classics. 1972. ISBN 978-0-14-043331-9.; Della Pittura, in Italian (1804 [1434]).

- Momus, Latin text and English translation, 2003 ISBN 0-674-00754-9

- De re aedificatoria (1452, Ten Books on Architecture). Alberti, Leon Battista. De re aedificatoria. On the art of building in ten books. (translated by Joseph Rykwert, Robert Tavernor and Neil Leach). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1988. ISBN 0-262-51060-X. ISBN 978-0-262-51060-8. Latin, French and Italian editions

- De Cifris A Treatise on Ciphers (1467), trans. A. Zaccagnini. Foreword by David Kahn, Galimberti, Torino 1997.

- Della tranquillitá dell'animo. 1441.

- "Leon Battista Alberti. On Painting. A New Translation an Critical Edition", Edited and Translated by Rocco Sinisgalli, Cambridge University Press, New York, May 2011, ISBN 978-1-107-00062-9

- I libri della famiglia, Italian edition

- "Dinner pieces". A Translation of the Intercenales by David Marsh. Center for Medieval and Early Renaissance Studies, State University of New York, Binghampton 1987.

- "Descriptio urbis Romae. Leon Battista Alberti's Delineation of the city of Rome". Peter Hicks, Arizona Board of Regents for Arizona State university 2007.

Notes

- ↑ James Beck, "Leon Battista Alberti and the 'Night Sky' at San Lorenzo", Artibus et Historiae 10, No. 19 (1989:9–35), p. 9.

- 1 2 3 4 Melissa Snell, Leon Battsta Alberti, About.com: Medieval History.

- 1 2 3 4 5 The Renaissance:a Illustrated Encyclopedia, Octopus (1979) ISBN 0706408578

- 1 2 3 4 Jacob Burckhardt in The Civilization of the Renaissance Italy, 2.1, 1860.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Joseph Rykwert, ed., Leon Baptiste Alberti, Architectul Design, Vol 49 No 5-6, London

- 1 2 3 4 Vasari, The Lives of the Artists

- ↑ Leone Battista Alberti, On Painting, editor John Richard Spencer, 1956, p. 43.

- ↑ Nader El-Bizri, "A Philosophical Perspective on Alhazen’s Optics," Arabic Sciences and Philosophy, vol. 15, issue 2 (2005), pp. 189–218 (Cambridge University Press).

- 1 2 3 4 5 Liukkonen, Petri. "Leon Battista Alberti". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 10 February 2015.

- 1 2 Alberti,Leon Battista. On the Art of Building in Ten Books. Trans. Leach, N., Rykwert, J., & Tavenor, R. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1988

- ↑ Center for Palladian Studies in America, Inc., Palladio's Literary Predecessors

- ↑ D. Mazzini, S. Simone, Villa Medici a Fiesole. Leon Battista Alberti e il prototipo di villa rinascimentale, Centro Di, Firenze 2004

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Franco Borsi. Leon Battista Alberti. New York: Harper & Row, (1977)

- ↑ Liane Lefaivre, Leon Battista Alberti's Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1997

- ↑ De Pictura, book III: Ergo semper quae picturi sumus, ea a natura sumamus, semperque ex his quaeque pulcherrima et dignissima deligamus.

References

- Gille, Bertrand (1970). "Alberti, Leone Battista". Dictionary of Scientific Biography 1. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 96–98. ISBN 0-684-10114-9.

- Wright, D.R. Edward, "Alberti's De Pictura: Its Literary Structure and Purpose", Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 47, 1984 (1984), pp. 52–71.

- Robert Tavernor, On Alberti and the Art of Building. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0-300-07615-8.

- Mark Jarzombek, “The Structural Problematic of Leon Battista Alberti's De pictura”, Renaissance Studies 4/3 (September 1990): 273–285.

- Anthony Grafton, Leon Battista Alberti. Master Builder of the Italian Renaissance. New York 2000

- Fontana-Giusti, Gordana. 'Walling and the city: the effects of walls and walling within the city space', The Journal of Architecture pp 309–45 Volume 16, Issue 3, London & New York: Routledge, 2011 http://www.tandfonline.com/toc/rjar20/16/3#.UlGA8ChTNUQ

- Korolija Fontana-Giusti, Gordana, 'The Cutting Surface: On Perspective as a Section, Its Relationship to Writing, and Its Role in Understanding Space' AA Files No. 40 (Winter 1999), pp. 56–64 London: Architectural Association School of Architecture Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/29544173

- Günther Fischer, Leon Battista Alberti. Sein Leben und seine Architekturtheorie. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft Darmstadt 2012

- Michel Paoli, Leon Battista Alberti, Torino 2007*

- Francesco Borsi, Leon Battista Alberti. Das Gesamtwerk. Stuttgart 1982

- Manfredo Tafuri, Interpreting the Renaissance: Princes, Cities, Architects, trans. Daniel Sherer. New Haven 2006.

- Les Livres de la famille d'Alberti, Sources, sens et influence, sous la direction de Michel Paoli, avec la collaboration d'Elise Leclerc et Sophie Dutheillet de Lamothe, préface de Françoise Choay, Paris, Classiques Garnier, 2013.

- Vasari, The Lives of the Artists Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-19-283410-X

External links

| Library resources about Leon Battista Alberti |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Leone Battista Alberti. |

- Albertian Bibliography on line

- MS Typ 422.2. Alberti, Leon Battista, 1404–1472. Ex ludis rerum mathematicarum : manuscript, [14--]. Houghton Library, Harvard University.

- Palladio's Literary Predecessors

- "Learning from the City-States? Leon Battista Alberti and the London Riots", Caspar Pearson, Berfrois, 26 September 2011

- Online resources for Alberti's buildings

- Alberti Photogrammetric Drawings

- S. Andrea, Mantua, Italy

- Sta. Maria Novella, Florence, Italy

- Alberti's works online

- De pictura/Della pittura, original Latin and Italian texts (English translation)

- Libri della famiglia – Libro 3 – Dignità del volgare on audio MP3

- Momus, (printed in Rome in 1520), full digital facsimile, CAMENA Project

- The Architecture of Leon Battista Alberti in Ten Books, (printed in London in 1755), full digital facsimile, Linda Hall Library

- Read online "Ten Books on Architecture by Leone Battista Alberti"

- Works of Alberti, book facsimiles via archive.org

|