National delimitation in the Soviet Union

National delimitation in the Soviet Union refers to the process of creating well-defined national territorial units (Soviet socialist republics – SSR, autonomous Soviet socialist republics – ASSR, autonomous oblasts (provinces), raions (districts) and okrugs from the ethnic diversity of the Soviet Union and its subregions. The Russian term for this Soviet state policy is razmezhevanie (Russian: национально-территориальное размежевание, natsionalno-territorialnoye razmezhevaniye), which is variously translated in English-language literature as national-territorial delimitation, demarcation, or partition.[1] National delimitation is part of a broader process of changes in administrative-territorial division, which also changes the boundaries of territorial units, but is not necessarily linked to national or ethnic considerations.[2] National delimitation in the Soviet Union is distinct from nation-building (Russian: национальное строительство), which typically refers to the policies and actions implemented by the government of a national territorial unit (a nation state) after delimitation. In most cases National delimitation in the Soviet Union was followed by korenizatsiya.

Policies of national delimitation in the Soviet Union

Pre-1917 Russia was an imperial state, not a nation. In the 1905 Duma elections the nationalist parties received only 9 percent of all votes.[3] The many non-Russian ethnic groups that inhabited the Russian Empire were classified as inorodtsy, or aliens. The Soviet Russia that took over from the Russian Empire in 1917 was not a nation-state, nor was the Soviet leadership committed to turning their country into such a state. In the early Soviet period, even voluntary assimilation was actively discouraged, and the promotion of the national self-consciousness of the non-Russian populations was attempted. Each officially recognized ethnic minority, however small, was granted its own national territory where it enjoyed a certain degree of autonomy, national schools, and national elites.[4] A written national language (if it had been lacking), national language planning, native-language press, and books written in the native language came with the national territory.[5] The attitudes towards many ethnic minorities changed dramatically in the 1930s–1940s under the leadership of Joseph Stalin (despite his own Georgian ethnic roots) with the advent of a repressive policy featuring abolition of the national institutions, ethnic deportations, national terror, and Russification (mostly towards those with cross-border ethnic ties to foreign nation-states in the 1930s or compromised in the view of Stalin during the Great Patriotic War in the 1940s), although nation-building often continued simultaneously for others.[4]

After the establishment of the Soviet Union within the boundaries of the former Russian Empire, the Bolshevik government began the process of national delimitation and nation building, which lasted through the 1920s and most of the 1930s. The project attempted to build nations out of the numerous ethnic groups in the Soviet Union. Defining a nation or politically conscious ethnic group was in itself a politically charged issue in the Soviet Union. In 1913, Stalin, in his work Marxism and the National Question, which subsequently became the cornerstone of the Soviet policy towards nationalities, defined a nation as "a historically constituted, stable community of people, formed on the basis of a common language, territory, economic life, and psychological makeup manifested in a common culture".[6] Many of the subject nationalities or communities in the Russian Empire did not fully meet these criteria. Not only cultural, linguistic, religious and tribal diversities made the process difficult but also the lack of a political consciousness of ethnicity among the people was a major obstacle to this process. Still, the process relied on the Declaration of the Rights of the Peoples of Russia, adopted by the Bolshevik government on 15 November 1917, immediately after the October Revolution, which recognized equality and sovereignty of all the peoples of Russia; their right for free self-determination, up to and including secession and creation of an independent state; freedom of religion; and free development of national minorities and ethnic groups on the territory of Russia.[7]

The Soviet Union (or more formally USSR – the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) was established in 1922 as a federation of nationalities, which eventually came to encompass 15 major national territories, each organized as a Union-level republic (Soviet Socialist Republic or SSR). All 15 national republics, created between 1917 and 1940, had constitutionally equal rights and equal standing in the formal structure of state power. The largest of the 15 republics – Russia – was ethnically the most diverse and from the very beginning it was constituted as the RSFSR – the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, a federation within a federation. The Russian SFSR was divided in the early 1920s into some 30 autonomous ethnic territories (Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republics – ASSR and autonomous oblasts – AO), many of which exist to this day as ethnic republics within the Russian Federation. There was also a very large number of lower-level ethnic territories, such as national districts and national village soviets. The exact number of ASSR and AO varied over the years as new entities were created while old entities switched from one form to another, transformed into Union-level republics (e.g., Kazakh and Kyrgyz SSR created in 1936, Moldovan SSR created in 1940), or were absorbed into larger territories (e.g., Crimean ASSR absorbed into the RSFSR in 1945 and Volga German ASSR absorbed into RSFSR in 1941).

The first population census of the USSR in 1926 listed 176 distinct nationalities.[8] Eliminating excessive detail (e.g., four ethnic groups for Jews and five ethnic groups for Georgians) and omitting very small ethnic groups, the list was condensed into 69 nationalities.[9] These 69 nationalities lived in 45 nationally delimited territories, including 16 Union-level republics (SSR) for the major nationalities, 23 autonomous regions (18 ASSR and 5 autonomous oblasts) for other nationalities within the Russian SFSR, and 6 autonomous regions within other Union-level republics (one in Uzbek SSR, one in Azerbaijan SSR, one in Tajik SSR, and three in Georgian SSR).

Higher-level autonomous national territories in the Soviet Union[9]

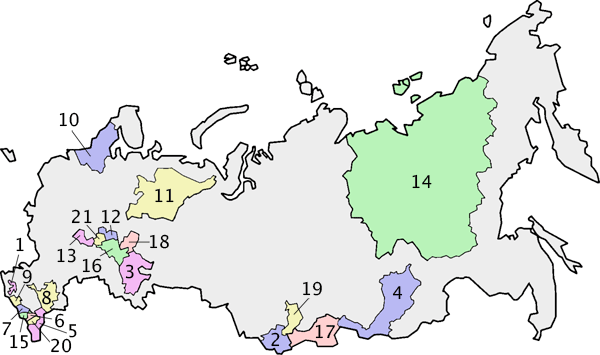

Map showing the ethnic republics of the Russian Federation (2008) that succeeded the national territories of Russian SFSR (pre-1990)

| ||

|

8. Kalmykia |

15. North Ossetia-Alania | |

Despite the general policy of granting national territories to all ethnic groups, several nationalities remained without their own territories in the 1920s and the 1930s. These included Poles, Bulgarians, Greeks, Hungarians, Gypsies, Uigurs, Koreans, and Gagauz (today the Gagauz live in a compact area in the south of Moldova, where they enjoy a measure of autonomy). The Volga Germans lost their national territory with the outbreak of World War II in 1941. The peoples of the North had neither autonomous republics nor autonomous oblasts, but since the 1930s they have been organized in 10 national okrugs, such as the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, the Koryak Autonomous Okrug, the Nenets Autonomous Okrug, and others.[9]

Besides national republics, oblasts, and okrugs, several hundred national districts (with populations between 10,000 and 50,000) and several thousand national townships (population 500 to 5,000) were established. In some cases this policy required voluntary or forced resettlement in both directions to create a compact population. Ethnic left immigration and the return of non-Russian émigrés to the Soviet Union during the New Economic Policy, albeit perceived as an easy cover for espionage, were not discouraged and proceeded quite actively, contributing to nation-building.[4]

Soviet fear of foreign influence gained momentum from sporadic ethnic guerilla uprisings along the entire Soviet frontier throughout the 1920s. The Soviet government was particularly concerned about the loyalty of the Finnish, Polish, and German populations. However, in July 1925 the Soviet authorities felt secure enough and in order to project Soviet influence outwards, exploiting cross-border ethnic ties, granted national minorities in the border regions more privileges and national rights than those in the central regions.[4] This policy was implemented especially successfully in the Ukrainian SSR, which at first indeed succeeded in attracting the population of Polish Kresy. However, some Ukrainian communists claimed neighboring regions even from the Russian SFSR.[4]

National delimitation in Central Asia

After the Russian Revolution, the entire space occupied today by Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and the southern part of Kazakhstan consisted of three administrative territorial units: the Turkestan ASSR, created in April 1918 within the Russian SFSR, and the two successor states of the Emirate of Bukhara and the Khanate of Khiva, which were transformed into Bukhara and Khorezm People's Soviet Republics following the takeover by the Red Army in 1920. North of Turkestan ASSR lay the Kirghiz Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (Kirghiz ASSR, Kirgizistan ASSR on the map), which was created on 26 August 1920 in the territory coinciding with the northern part of today's Kazakhstan (the southern part of Kazakhstan, south of the Aral Sea–Lake Balkhash line, was part of Turkestan ASSR in 1920).

In 1924, Turkestan ASSR, i.e., roughly the southern half of Soviet Central Asia, was partitioned into two Soviet Socialist Republics (SSR), Turkmen SSR and Uzbek SSR. Turkmen SSR matched the borders of today's Turkmenistan and it was created as a home for the Turkmens of Soviet Central Asia. The Bukhara and Khorezm People's Soviet Republics were absorbed into Uzbek SSR, which also included other territories inhabited by Uzbeks as well as those inhabited by ethnic Tajiks. At the same time, Tajik ASSR was created within Uzbek SSR for the Tajik ethnic population and after five years, in 1929, it was separated from Uzbek SSR and upgraded to the status of Soviet Socialist Republic (Tajik SSR). Kirghiz SSR (today's Kyrgyzstan) was created only in 1936; between 1929 and 1936 it existed as the Kara-Kirghiz Autonomous Oblast (province) within the Russian SFSR.[10] Kazakh SSR was also created at that time (5 December 1936), thus completing the process of national delimitation of Soviet Central Asia into five Soviet Socialist Republics that in 1991 would become five independent states.

Bitter debates accompanied the partition of Uzbek SSR and Tajik SSR in 1929, focusing especially on the status of Bukhara, Samarkand, and the Surxondaryo Region, all of which had sizeable, if not dominant, Tajik populations. The final decision negotiated by the Uzbek and Tajik parties, not without strong involvement of the Communist Party, left these three Tajik-populated territories within the Turkic-populated Uzbek SSR. Tajik SSR was created on 5 December 1929 as the home for most of the ethnic Tajiks in Soviet Central Asia within the boundaries of present-day Tajikistan.[11]

Nation-building for ethnic minorities

In the 1920s and the 1930s, the policy of national delimitation, which assigned national territories to ethnic groups and nationalities, was followed by nation-building, attempting to create a full range of national institutions within each national territory. Each officially recognized ethnic minority, however small, was granted its own national territory where it enjoyed a certain degree of autonomy, in addition to, and national elites.[4] A written national language was developed (if it had been lacking), national language planning was implemented, native teachers were trained, and national schools were established. This was always accompanied by native-language press and books written in the native language. National elites were encouraged to develop and take over the leading administrative and Party positions, sometimes in proportions exceeding the proportion of the native population.[5]

With the grain requisition crises, famines, troubled economic conditions, international destabilization and the reversal of the immigration flow in the early 1930s, the Soviet Union became increasingly worried about a possible disloyalty of diaspora ethnic groups with cross-border ties (especially Finns, Germans and Poles), residing along its western borders, which eventually led to the start of Stalin's repressive policy towards them.[4]

Each adult citizen's ethnicity (Russian: национальность) was necessarily recorded in his passport after the introduction of the passport system in the Soviet Union in 1932 and was determined by his choice between his parents' ethnicities (practice that didn't exist in Russian Empire and is abolished in today's Russia).

However, the important question is: why did the communist rulers of the USSR need to create a national consciousness among people, given that it is generally used by the bourgeoisie to curtail the class struggle? The reason lies in both the pre-revolutionary and post-revolutionary policies of the Bolshevik Party. Before the revolution, Vladimir Lenin used demands for national autonomy by the non-Russian communities as a tool for gaining power against the tsarist regime; he promised autonomy to these communities, even the right to secede. After the revolution, reifying national identities was seen as a solution for local administrative problems. Sovietization was the ultimate goal behind the nation-building process. In local administrative units, the "rulers" needed to be natives in order to make the non-Russian populations feel that they had been granted national self-determination, and this was accomplished via the politics dubbed Korenizatsiya ("indigenization"). Autonomous states like Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and others had their own ruling communist parties and native elites, although they were actually under the explicit control of the overall Communist Party of the Soviet Union. There was also another aspect of this project: it was not aimed at the differentiation of nations but at unifying them over time. The implicit assumption was that after a short (10–20 year) period, bourgeois nationalism would be abandoned and support for a worker-state would follow. The Bolsheviks' aim was not a loose federation but a completely unified modern socialist state.[5]

The Bolsheviks’ plan was to identify the total sum of all national, cultural, linguistic, and territorial diversities under their rule and establish scientific criteria to identify which groups of people were entitled to the description of 'nation'. This task relied on the existing work of tsarist-era ethnographers and statisticians, as well as new research conducted under Soviet auspices. Because most people did not know what is meant by a nation, some of them simply gave names when asked about ethnic group. Many groups were thought to be biologically similar, but culturally distinct. In Central Asia, many identified their "nation" as "Muslim." In other cases, geography made the difference, or even whether one lived in a town versus the countryside. Principally, however, dialects or languages formed the basis for distinguishing between various nations. The results were often contradictory and confusing. More than 150 nations were counted in Central Asia alone. Some were quickly subordinated to others, with communities which had hitherto been counted as "nations" now deemed to be simply tribes. As a result, the number of nations shrunk over the decades.[5]

Korean minorities: a failed delimitation

The Korean minority population in the Russian Far East was one of the largest border minorities in the Soviet Union, facing in the 1920s and the 1930s the Japanese-occupied Korea on the other side. This minority had been gradually building up since the second half of the 19th century, as poor Korean peasants migrated across the border in search for land and livelihoods.[12] The Korean immigration increased dramatically during the early 1920s, after Japanese rule. From 1917 to 1926 the Soviet Korean population tripled to nearly 170,000 people, and by 1926 Koreans represented more than a quarter of the rural population of the Vladivostok region. Declared Soviet policy toward national minorities demanded the formation of a Korean autonomous territory for the large Korean community in the Russian Far East. The option of establishing a Korean ASSR in the Far East was seriously debated in Moscow but finally rejected in 1925 because of opposition from the local Russian population who feared competition for land and the political goal of maintaining a peaceful stance toward the Japanese. As a result, a contradictory policy emerged. On the one hand, smaller Korean national territories were authorized, with Korean-language schools and newspapers, and the policy line represented Koreans as a model Soviet national minority contrasted with the Korean population suffering under the yoke of Japanese occupation across the border. On the other hand, the central government confirmed a plan (6 December 1926) to resettle half of the Soviet Koreans (88,000 people) north of Khabarovsk on suspicions of disloyalty to the Soviet Union. However, the northward resettlement plan had not been implemented by 1928 for a variety of political and budgetary reasons. By 1931, when the plan was officially abandoned, only 500 Korean families (2,500 individuals) had been resettled in the north.[4]

The resettlement plans were revived with new vigor in August 1937, ostensibly with the purpose of suppressing "the penetration of the Japanese espionage into the Far Eastern Krai". This time, however, the direction of resettlement was westward, to Soviet Central Asia. From September to October 1937, more than 172,000 of Soviet Koreans were deported from the border regions of the Russian Far East to Kazakh SSR and Uzbek SSR (the latter including Karakalpak ASSR).[13][14] The deportees expected a Korean ASSR to be created in Central Asia, but they never received a national territory, although the deported Koreans were settled in separate Korean collective farms with Korean-language schools, a Korean publishing house, a Korean newspaper for all of Central Asia, and even a Korean teachers' college.[4] A significant population of ethnic Koreans still exists in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

See also

References

- ↑ Hasan Ali Karasar, "The Partition of Khorezm and the Positions of Turkestanis on Razmezhevanie", Europe-Asia Studies, 60(7):1247-1260 (September 2008).

- ↑ Тархов, Сергей. Изменение административно-территориального деления России в XII-XX в.

- ↑ Richard Overy (2004). The Dictators: Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Russia. W.W Norton Company, Inc. p. 545.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Martin, Terry (1998). "The Origins of Soviet Ethnic Cleansing". The Journal of Modern History 70 (4), 813-861.

- 1 2 3 4 Slezkine, Yuri (1994). "The USSR as a Communal Apartment, or How a Socialist State Promoted Ethnic Particularism". Slavic Review 53 (2), 414–52.

- ↑ Definition of a nation in J. Stalin, Marxism and the National Question, March–May 1913; Russian original: J. Stalin, Collected Works in 16 Volumes, volume 2.

- ↑ Declaration of Rights of the Peoples of Russia, 15 November 1917, Big Soviet Encyclopedia, on-line edition. Retrieved 15 November 2008.

- ↑ List of nationalities in the 1926 USSR census on demoscrope.ru

- 1 2 3 Gerhard Simon, Nationalism and Policy Toward the Nationalities in the Soviet Union: From Totalitarian Dictatorship to Post-Stalinist Society, Westview Press, Boulder, CO, 1991.

- ↑ William Fierman, ed., Soviet Central Asia: The Failed Transformation, Westview Press, Boulder, CO, 1991, pp. 16-18.

- ↑ Rahim Masov, The History of the Clumsy Delimitation, Irfon Publ. House, Dushanbe, 1991 (Russian). English translation: The History of a National Catastrophe, transl. Iraj Bashiri, 1996.

- ↑ A.N. Li, Korean diaspora in Kazakhstan: Koryo saram, retrieved 5 November 2008 (Russian)

- ↑ German Kim, "Korean diaspora in Kazakhstan", Slavic Research Center, Hokkaido University, 1989

- ↑ "History of deportation of Far Eastern Koreans to Karakalpakstan (1937-1938)" (Russian)

Further reading

- John Everett-Heath (2003) Central Asia: History, Ethnicity, Modernity, Routledge-Curzon, ISBN 0-7007-0956-8

- Arne Haugen (2004) The Establishment of National Republics in Central Asia, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 1-4039-1571-7

- Terry Martin(2001). The Affirmative Action Empire: Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923-1939, Cornell University Press, ISBN 0-8014-8677-7

- Oliver Roy (2000) The New Central Asia: The Creation of Nations, NYU Press, ISBN 0-8147-7555-1