Leipzig

| Leipzig | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

From top: Skyline of Leipzig centre, Monument to the Battle of the Nations at night, Federal Administrative Court of Germany, New Town Hall, City-Hochhaus Leipzig and the Augusteum of the Leipzig University | |||||||

| |||||||

Leipzig | |||||||

| Coordinates: 51°20′N 12°23′E / 51.333°N 12.383°ECoordinates: 51°20′N 12°23′E / 51.333°N 12.383°E | |||||||

| Country | Germany | ||||||

| State | Saxony | ||||||

| District | Urban districts of Germany | ||||||

| Government | |||||||

| • Lord Mayor | Burkhard Jung (SPD) | ||||||

| Area | |||||||

| • City | 297.36 km2 (114.81 sq mi) | ||||||

| Population (2014-12-31)[1] | |||||||

| • City | 544,479 | ||||||

| • Density | 1,800/km2 (4,700/sq mi) | ||||||

| • Metro | 1,001,220 (LUZ)[2] | ||||||

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) | ||||||

| Postal codes | 04001-04357 | ||||||

| Dialling codes | 0341 | ||||||

| Vehicle registration | L | ||||||

| Website | www.leipzig.de | ||||||

Leipzig (/ˈlaɪpsɪɡ/; German: [ˈlaɪptsɪç]) is the largest city in the federal state of Saxony, Germany. With its population of 544,479 inhabitants[3] (1,001,220 residents in the larger urban zone)[2] Leipzig, one of Germany's top 15 cities by population, is located about 160 kilometers (99 miles) southwest of Berlin at the confluence of the White Elster, Pleisse, and Parthe rivers at the southerly end of the North German Plain.

Leipzig has been a trade city since at least the time of the Holy Roman Empire.[4] The city sits at the intersection of the Via Regia and Via Imperii, two important Medieval trade routes. Leipzig was once one of the major European centers of learning and culture in fields such as music and publishing.[5] Leipzig became a major urban center within the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) after World War II, but its cultural and economic importance declined[5] despite East Germany being the richest economy in the Soviet Bloc.[6]

Leipzig later played a significant role in instigating the fall of communism in Eastern Europe, through events which took place in and around St. Nicholas Church. Since the reunification of Germany, Leipzig has undergone significant change with the restoration of some historical buildings, the demolition of others, and the development of a modern transport infrastructure.[7] Leipzig today is an economic center and the most livable city in Germany, according to the GfK marketing research institution.[8] Oper Leipzig is one of the most prominent opera houses in Germany, and Leipzig Zoological Garden is one of the most modern zoos in Europe and ranks first in Germany and second in Europe according to Anthony Sheridan.[9][10] Leipzig is currently listed as Gamma World City[11] and Germany's "Boomtown".[12]

History

Name

Leipzig is derived from the Slavic word Lipsk, which means "settlement where the linden trees (British English: lime trees; U.S. English: basswood trees) stand".[13] An older spelling of the name in English is Leipsic. The Latin name Lipsia was also used.[14]

In 1937 the Nazi government officially renamed the city Reichsmessestadt Leipzig (Imperial Trade Fair City Leipzig).[15]

More recently, the city is sometimes nicknamed "Boomtown of eastern Germany", "Hypezig" or "The new Berlin" for being celebrated by the media as a hip urban center for the vital lifestyle and creative scene with many startups.[16][17][18][19][20] and is well known as Hero City (Heldenstadt) according to the Heldenstadt blog.[21]

Origins

Leipzig was first documented in 1015 in the chronicles of Bishop Thietmar of Merseburg as 'urbs Libzi' (Chronikon VII, 25), and endowed with city and market privileges in 1165 by Otto the Rich. The Leipzig Trade Fair, started in the Middle Ages, became an event of international importance and is the oldest remaining trade fair in the world.

There are records of commercial fishing operations on the river Pleisse in Leipzig dating back to 1305, when the Margrave Dietrich the Younger granted the fishing rights to the church and convent of St. Thomas.[22]

There were a number of monasteries in and around the city, including a Benedectine monastery after which the Barfußgäßchen (Barefoot Alley) is named and a monastery of Irish monks (Jacobskirche, destroyed in 744) near the present day Ranstädter Steinweg (old Via Regia).

The foundation of the University of Leipzig in 1409 initiated the city's development into a center of German law and the publishing industry, and towards being the location of the Reichsgericht (Imperial Court of Justice), and the German National Library (founded in 1912).

During the Thirty Years' War, two battles took place in Breitenfeld, about five miles outside Leipzig city walls. The first Battle of Breitenfeld took place in 1631 and the second in 1642. Both battles resulted in victories for the Swedish-led side.

On 24 December 1701, an oil-fueled street lighting system was introduced. The city employed light guards who had to follow a specific schedule to ensure the punctual lighting of the 700 lanterns.

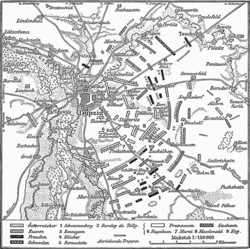

Nineteenth century

The Leipzig region was the arena of the 1813 Battle of Leipzig between Napoleonic France and an allied coalition of Prussia, Russia, Austria, and Sweden. It was the largest battle in Europe prior to World War I and the coalition victory ended Napoleon's presence in Germany and would ultimately lead to his first exile on Elba. In 1913 the Monument to the Battle of the Nations celebrating the centenary of this event was completed.

A terminus of the first German long distance railway to Dresden (the capital of Saxony) in 1839, Leipzig became a hub of Central European railway traffic, with Leipzig Hauptbahnhof the largest terminal station by area in Europe. The train station has two grand entrance halls, the eastern one for the Royal Saxon State Railways and the western one for the Prussian state railways.

Leipzig became a center of the German and Saxon liberal movements. The first German labor party, the General German Workers' Association (Allgemeiner Deutscher Arbeiterverein, ADAV) was founded in Leipzig on 23 May 1863 by Ferdinand Lassalle; about 600 workers from across Germany travelled to the foundation on the new railway line. Leipzig expanded rapidly to more than 700.000 inhabitants. Huge Gründerzeit areas were built, which mostly survived both war and post-war demolition.

Twentieth century

With the opening of a fifth production hall in 1907, the Leipziger Baumwollspinnerei became the largest cotton mill company on the continent, housing over 240,000 spindles. Daily production surpassed 5 million kilograms of yarn.[23]

The city's mayor from 1930 to 1937, Carl Friedrich Goerdeler was a noted opponent of the Nazi regime in Germany. He resigned in 1937 when, in his absence, his Nazi deputy ordered the destruction of the city's statue of Felix Mendelssohn. On Kristallnacht in 1938, one of the city's most architecturally significant buildings, the 1855 Moorish Revival Leipzig synagogue was deliberately destroyed.

Several thousand forced laborers were stationed in Leipzig during World War II.

The city was also heavily damaged by Allied bombing during World War II. Unlike its neighboring city of Dresden this was largely conventional bombing, with high explosives rather than incendiaries. The resultant pattern of loss was a patchwork, rather than wholesale loss of its center, but was nevertheless extensive.

The Allied ground advance into Germany reached Leipzig in late April 1945. The U.S. 2nd Infantry Division and U.S. 69th Infantry Division fought into the city on 18 April and completed its capture after fierce urban combat, in which fighting was often house-to-house and block-to-block, on 19 April 1945.[24] In April 1945 the Deputy Mayor of Leipzig, Ernest Lisso, his wife, daughter and a Volkssturm Major Walter Dönicke committed suicide in the Leipzig City Hall.

The U.S. turned the city over to the Red Army as it pulled back from the line of contact with Soviet forces in July 1945 to the predesignated occupation zone boundaries. Leipzig became one of the major cities of the German Democratic Republic (East Germany).

In the mid-20th century, the city's trade fair assumed renewed importance as a point of contact with the Comecon Eastern Europe economic bloc, of which East Germany was a member. At this time, trade fairs were held at a site in the south of the city, near the Monument to the Battle of the Nations.

In October 1989, after prayers for peace at St. Nicholas Church, established in 1983 as part of the peace movement, the Monday demonstrations started as the most prominent mass protest against the East German regime.[25][26] Since the reunification of Germany, Leipzig has undergone significant change with the restoration of some historical buildings, the demolition of others, and the development of a modern transport infrastructure. Nowadays, Leipzig is an economic center in eastern Germany. Leipzig was the German candidate for the 2012 Summer Olympics, but was unsuccessful. After ten years of construction, the Leipzig City Tunnel opened on 14 December 2013.[27]

Geography

Leipzig lies at the confluence of the rivers White Elster, Pleisse, and Parthe, in the Leipzig Bay, on the most southerly part of the North German Plain, which is the part of the North European Plain in Germany. The site is characterized by swampy areas such as the Leipzig Riverside Forest, though there are also some limestone areas to the north of the city. The landscape is mostly flat though there is also some evidence of moraine and drumlins.

Although there are some forest parks within the city limits, the area surrounding Leipzig is relatively unforested. During the 20th century, there were several open-cast mines in the region, many of which are being converted to use as lakes.[28]

Leipzig is also situated at the intersection of the ancient roads known as the Via Regia (King's highway), which traversed Germanic lands in an east-west direction, and Via Imperii (Imperial Highway), a north-south road.

Leipzig was a walled city in the Middle Ages and the current "ring" road around the historic center of the city corresponds to the old city walls.

Districts and neighboring regions

Leipzig has been divided administratively since 1992 into ten urban districts, which contain 63 subdistricts. Some of these correspond to outlying villages which were annexed by Leipzig.

| District | Pop. | Area km² | Pop. per km² |

|---|---|---|---|

| Center | 49,562 | 13,88 | 3,570 |

| Northeast | 41,186 | 26.29 | 1.566 |

| East | 69,666 | 40.74 | 1,710 |

| Southeast | 51,139 | 34.65 | 1,476 |

| South | 57,434 | 16.92 | 3,394 |

| Southwest | 45,886 | 46.67 | 983 |

| West | 51,276 | 14.69 | 3,491 |

| Old West | 46,009 | 26.09 | 1,764 |

| Northwest | 28,036 | 39.09 | 717 |

| North | 57,559 | 38.35 | 1,501 |

| Delitzsch | Jesewitz | ||

| Schkeuditz | Rackwitz | Taucha | |

.svg.png) |

Borsdorf | Brandis | |

| Markranstädt | Markkleeberg | Naunhof | |

| Kitzen | Zwenkau | Grosspoesna | |

Climate

Leipzig has an oceanic climate (Cfb in the Köppen climate classification). Winters are variably mild to cold, with an average of around 1 °C (34 °F). Summers are generally warm, averaging at 19 °C (66 °F) with daytime temperatures of 24 °C (75 °F). Precipitation is around twice as small in winter than summer, however, winters aren't dry. The amount of sunshine differs quite between winter and summer, with around 51 hours of sunshine in December (1.7 hours a day) on average and 229 hours of sunshine in July (7.4 hours a day).

| Climate data for Leipzig/Halle, Germany for 1981–2010, temperature records for 1973-2013 (Source: DWD) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.9 (60.6) |

18.6 (65.5) |

23.0 (73.4) |

29.5 (85.1) |

31.9 (89.4) |

34.8 (94.6) |

36.6 (97.9) |

37.2 (99) |

32.9 (91.2) |

28.2 (82.8) |

18.7 (65.7) |

16.5 (61.7) |

37.2 (99) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 3.2 (37.8) |

4.3 (39.7) |

8.7 (47.7) |

13.9 (57) |

19.0 (66.2) |

21.7 (71.1) |

24.5 (76.1) |

24.1 (75.4) |

19.3 (66.7) |

14.0 (57.2) |

7.6 (45.7) |

3.6 (38.5) |

13.67 (56.61) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.5 (32.9) |

1.1 (34) |

4.7 (40.5) |

8.9 (48) |

13.8 (56.8) |

16.5 (61.7) |

19.0 (66.2) |

18.6 (65.5) |

14.4 (57.9) |

9.8 (49.6) |

4.7 (40.5) |

1.3 (34.3) |

9.45 (49.01) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −2.2 (28) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

1.1 (34) |

4.1 (39.4) |

8.5 (47.3) |

11.5 (52.7) |

13.8 (56.8) |

13.6 (56.5) |

10.1 (50.2) |

6.2 (43.2) |

2.0 (35.6) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

5.47 (41.85) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −27.6 (−17.7) |

−21.6 (−6.9) |

−16.6 (2.1) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

1.8 (35.2) |

5.7 (42.3) |

5.5 (41.9) |

0.5 (32.9) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−12.9 (8.8) |

−20.2 (−4.4) |

−27.6 (−17.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 31.9 (1.256) |

26.3 (1.035) |

38.8 (1.528) |

39.6 (1.559) |

46.9 (1.846) |

54.8 (2.157) |

68.9 (2.713) |

63.1 (2.484) |

49.9 (1.965) |

31.0 (1.22) |

43.4 (1.709) |

39.8 (1.567) |

534.10 (21.0276) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 62.8 | 77.8 | 124.5 | 181.7 | 227.4 | 224.8 | 229.0 | 213.1 | 160.9 | 122.9 | 61.5 | 51.1 | 1,737.3 |

| Source: Data derived from Deutscher Wetterdienst, note: sunshine hours are from 1991-2013 [30] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

Leipzig has a population of about 540,000.[31] In 1930 the population reached its historical peak of over 700,000. It decreased steadily from 1950 until 1989 to about 530,000. In the 1990s the population decreased rather rapidly to 437,000 in 1998. This reduction was mostly due to outward migration and suburbanization. After almost doubling the city area by incorporation of surrounding towns in 1999, the number stabilized and started to rise again with an increase of 1,000 in 2000.[32] As of 2015, Leipzig is the fastest-growing city in Germany with over 500,000 inhabitants.[33] The growth of the past 10–15 years has mostly been due to inward migration. In recent years inward migration accelerated, reaching +10,800 in 2012.[34]

In the years following German reunification many people of working age took the opportunity to move to the states of the former West Germany to seek work. This was a contributory factor to falling birth rates. Births dropped from 7,000 in 1988 to less than 3,000 in 1994.[35] However, the number of children born in Leipzig has risen since the late 1990s. In 2011 it reached 5,490 newborns resulting in a RNI of -17.7 (-393.7 in 1995).[36]

The unemployment rate decreased from 18.2% in 2003 to 9.8% in 2014.[37][38]

The percentage of the population with an immigrant background is quite low compared with other German cities. As of 2012, only 5.6% of the population were foreigners, compared to the German overall average of 7.7%.[39]

The number of people with an immigrant background (immigrants and their children) grew from ~40,000 in 2010 to ~50,000 in 2012, making it 9.3% of the city's population.[40]

Number of minorities (1st and 2nd generation) in Leipzig by country of origin in 2014[41]

| Rank | Ancestry | Number | Foreigners | Germans |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7,382 | 2,700 | 4,682 | |

| 2 | 3,542 | 2,012 | 1,530 | |

| 3 | 3,196 | 2,242 | 954 | |

| 4 | 3,029 | 2,149 | 880 | |

| 5 | 2,106 | 1,758 | 348 | |

| 6 | 2,026 | 215 | 1,811 | |

| 7 | 1,909 | 1,242 | 667 | |

| 8 | 1,750 | 1,389 | 361 | |

| 9 | 1,564 | 1,169 | 395 | |

| 10 | 1,527 | 998 | 529 | |

| 11 | 1,510 | 1,234 | 276 |

Culture

Architecture

The historic downtown area of Leipzig features a renaissance style ensemble of buildings from the 16th century, including the old city hall in the market place. There are also several baroque period trading houses and former residences of rich merchants. As Leipzig grew considerably during the economic boom of the late 19th century, the town has many buildings in the historicist style representative of the Gründerzeit era. Approximately 35% of Leipzig's apartments are in buildings of this type. The new city hall, completed in 1905, displays the same style.

Some 64,000 apartments were built in Plattenbau buildings during the Communist rule in East Germany.[42] and although some of these have been demolished and the numbers living in this type of accommodation have declined in recent years, at least 10% of Leipzig's population (50,000 people) are still living in Plattenbau accommodation.[43] Grünau, for example, has approximately 40,000 people living in this sort of accommodation.[44]

The building of the St. Paul's Church was destroyed by the communists in 1968 to make room for a new main building of the university. After some debate, the city decided to establish a new, mainly secular building at the same location, called Paulinum, which was completed in 2012. Its architecture alludes to the look of the former church and it includes a room for religious use.

Many commercial buildings were built in the 1990s as a result of tax breaks after German reunification.

Tallest buildings and structures

The tallest structure in Leipzig is the chimney of the Stahl- und Hartgusswerk Bösdorf GmbH with 205 meters (672 ft). With 142 meters (466 ft), the City-Hochhaus Leipzig is the tallest high rise-building in Leipzig. From 1972 to 1973 it was Germanys tallest building.

| Buildings and structures | Image | Height in metres | Year | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chimney of Stahl- und Hartgusswerk Bösdorf GmbH |  |

205 | 1984 | |

| Funkturm Leipzig |  |

191 | 2015 | |

| DVB-T-Sendeturm |  |

190 | 1986 | |

| City-Hochhaus Leipzig | .jpg) |

142 | 1972 | Total height 153 m, tallest building in Germany 1972-1973. Headquarter of European Energy Exchange. |

| Fernmeldeturm Leipzig | |

132 | 1995 | |

| Tower of New Town Hall |  |

115 | 1905 | Tallest Town hall in Germany |

| Wintergartenhochhaus |  |

106,8 | 1972 | Used as residential tower |

| Hotel The Westin Leipzig |  |

95 | 1972 | Hotel with skybar and restaurant |

| Monument to the Battle of the Nations |  |

91 | 1913 | Tallest monument in Europe. |

| St. Peters' | |

88,5 | 1885 | Leipzigs tallest church. |

| MDR-Hochhaus | |

65 | 2000 | MDR is one of Germanys public broadcaster. |

| Hochhaus Löhr’s Carree | |

65 | 1997 | Headquarter of Sachsen Bank and Sparkasse Leipzig. |

Main sights

- St. Thomas Church (Thomaskirche): Most famous as the place where Johann Sebastian Bach worked as a cantor and home to the renowned boys choir Thomanerchor

- Monument to Felix Mendelssohn in front of this church. Destroyed by the Nazis in 1936, it was rebuilt on 18 October 2008.

- St. Nicholas Church (Nikolaikirche), for which Bach was also responsible. The weekly Montagsgebet (Monday prayer) held here became in the 1980s the starting point of peaceful Monday demonstrations against the DDR regime.

- Monument to the Battle of the Nations (Völkerschlachtdenkmal) (Battle of the Nations Monument): one of the largest monuments in Europe, built to commemorate the victorious battle against Napoleonic troops

- Gewandhaus: home to the famous Gewandhaus Orchestra, it is the third building of that name

- Old City Hall: the old city hall was built in 1556 and houses a museum of the city's history

- New City Hall: the city's new administrative building was built upon the remains of the Pleissenburg, a castle that was the site of the 1519 debate between Johann Eck and Martin Luther

- City-Hochhaus Leipzig: built in 1972, the city's tallest building is one of the top 20 tallest buildings in Germany.[45]

- Auerbach's Cellar: a young Goethe ate and drank in this basement-level restaurant while studying in Leipzig; it is the venue of a scene from his play Faust

- Bundesverwaltungsgericht: Germany's federal administrative court was the site of the Reichsgericht, the highest state court between 1888 and 1945

- The Leipzig Botanical Garden is the oldest botanical garden in Germany

Among Leipzig's noteworthy institutions are the Leipzig Opera and the Leipzig Zoological Garden, the latter of which houses the world's largest zoological facilities for primates (monkey house). Leipzig's international trade fair center in the north of the city is home to the world's largest levitated glass hall.[46]

-

The Monument to the Battle of the Nations, one of the biggest monuments in Europe

-

Old town hall at market square

-

The new Augusteum and Paulinum of the University of Leipzig

-

The Gewandhaus

-

Inside Gondwanaland at Leipzig Zoological Garden

-

View over South Cemetery and the chapel complex

-

Russian church in Leipzig

-

Höfe am Brühl, new shopping center near downtown

-

German National Library in Leipzig

-

Old Leipzig bourse at night

-

The new Propstei church in May 2015, New Town Hall in the background

-

Johannapark with City-Hochhaus Leipzig and the tower of the New Town Hall in the background

-

Mädlerpassage

-

The well known Auerbachs Keller in the Mädlerpassage

-

Monument of Johann Sebastian Bach

-

Barthels Hof

Music

Johann Sebastian Bach worked in Leipzig from 1723 to 1750, conducting the St. Thomas Church Choir, at the St. Thomas Church, the St. Nicholas Church and the Paulinerkirche, the university church of Leipzig (destroyed in 1968). The composer Richard Wagner was born in Leipzig in 1813, in the Brühl. Robert Schumann was also active in Leipzig music, having been invited by Felix Mendelssohn when the latter established Germany's first musical conservatoire in the city in 1843. Gustav Mahler was second conductor (working under Artur Nikisch) at the Leipzig Theatre from June 1886 until May 1888, and achieved his first great recognition while there by completing and publishing Carl Maria von Weber's opera Die Drei Pintos, and Mahler also completed his own 1st Symphony while living there.

This conservatory is today the University of Music and Theatre Leipzig[47] A broad range of subjects are taught, including artistic and teacher training in all orchestral instruments, voice, interpretation, coaching, piano chamber music, orchestral conducting, choir conducting and musical composition in various musical styles. The drama departments teach acting and scriptwriting.

The Bach-Archiv for documentation and research of life and work of Bach and also of the Bach family was founded in Leipzig in 1950 by Werner Neumann. The Bach-Archiv organizes the prestigious International Johann Sebastian Bach Competition, initiated in 1950 as part of a music festival marking the bicentennial of Bach's death. The competition is now held every two years in three changing categories. The Bach-Archiv also organizes performances, especially the international festival Bachfest Leipzig (de) and runs the Bach-Museum.

The city's musical tradition is also reflected in the worldwide fame of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra under the baton of chief conductor Riccardo Chailly and the Thomas Church Choir.

The MDR Leipzig Radio Symphony Orchestra is Leipzig's second large symphony orchestra. Its current chief conductor is Kristjan Järvi. Both the Gewandhausorchester and the MDR Leipzig Radio Symphony Orchestra reside in the Gewandhaus concert hall.

For over 60 years Leipzig has been offering a "school concert[48] programme for children in Germany, with over 140 concerts every year in venues such as the Gewandhaus and over 40,000 children attending.

As for contemporary music, Leipzig is known for its independent music scene and subcultural events. Leipzig has for 20 years been home to the world's largest Gothic festival, the annual Wave-Gotik-Treffen (WGT), where thousands of fans of gothic and dark styled music from across Europe gather in the early summer. Leipzig Pop Up is an annual music trade fair for the independent music scene as well as a music festival taking place on Pentecost weekend.[49] Its most famous indie-labels are Moon Harbour Recordings (house) and Kann Records (House/Techno/Psychedelic). Several venues offer live music on a daily basis, including the Moritzbastei [50] which was once part of the city's fortifications, and is one of the oldest student clubs in Europe with concerts in various styles. For over 15 years "Tonelli's"[51] has been offering free weekly concerts every day of the week, though door charges may apply Saturdays.

The cover photo for Beirut's 2005 album Gulag Orkestar was, according to the sleeve notes, stolen from a Leipzig library by Zach Condon.

The city of Leipzig is also known in the metal community as the birthplace of Till Lindemann, best known as the lead vocalist of the band Rammstein, a band formed in 1994.

Arts

The city's contemporary arts highlight was the Neo Rauch retrospective opening in April 2010 at the Leipzig Museum of Fine Arts. This is a show devoted to the father of the New Leipzig School[52][53] of artists. According to The New York Times,[54] this scene "has been the toast of the contemporary art world" in the past decade. Furthermore, there are eleven galleries in the so-called Spinnerei,.[55]

The building complex of the Grassi Museum contains three more of Leipzig's major collections:[56] the Ethnography Museum, Applied Arts Museum, and Musical Instrument Museum (the last of which is run by the University of Leipzig). The university also runs the Museum of Antiquities.[57]

Annual events

- Auto Mobil International (AMI) motor show[58]

- AMITEC, trade fair for vehicle maintenance, care, servicing and repairs in Germany and Central Europe[59]

- A cappella: vocal music festival, organized by the Ensemble amarcord

- Bach-Fest: Johann Sebastian Bach-festival

- Christmas market (since 1767)

- Dok Leipzig: international festival for documentary and animated film

- Jazztage,[60] contemporary jazz festival

- Ladyfest Leipzig[61] (August) Emancipatoric, feminist Punk & Electro Festival

- Leipzig Book Fair: the second largest German book fair after Frankfurt

- Lichtfest Leipzig, festival celebrating the demonstrations leading up to the collapse of the East German regime

- OPER unplugged with Music Dance Theatre by Heike Hennig & Co[62]

- Stadtfest: city festival

- Wave-Gotik-Treffen at Pentecost: world's largest goth or "dark culture" festival

- Leipzig Pop Up[63]

Sports

More than 300 sport clubs in the city represent 78 different disciplines. Over 400 athletic facilities are available to citizens and club members.[64]

The German Football Association (DFB) was founded in Leipzig in 1900. The city was the venue for the 2006 FIFA World Cup draw, and hosted four first-round matches and one match in the round of 16 in the central stadium.

VfB Leipzig, now 1. FC Lokomotive Leipzig, won the first national Association football championship in 1903. The team has had a glorious past in international competition as well, having been champions of the 1965–66 Intertoto Cup, semi-finalists in the 1973–74 UEFA Cup, and runners-up in the 1986–87 European Cup Winners' Cup. In June 2009 Red Bull entered the local market after being denied the right to buy into FC Sachsen Leipzig in 2006. The newly founded RB Leipzig is now attempting to come up through the ranks of German football to bring Bundesliga football back to the region.[65]

Leipzig also hosted the Fencing World Cup in 2005 and hosts a number of international competitions in a variety of sports each year.

Since the beginning of the 20th century Ice hockey gained popularity and several local clubs established departments dedicated to that sport.[66]

From 1950 to 1990 Leipzig was host of the Deutsche Hochschule für Körperkultur (DHfK) (German highschool for physical culture), the national sport university of the GDR.

Handball-Club Leipzig is one of the most successful women's handball clubs in Germany, winning 20 domestic championships since 1956 and 3 Champions League titles. SC DHfK Leipzig Handball is men's handball club in Leipzig were six times (1959, 1960, 1961, 1962, 1965 and 1966) champion of East Germany handball league and was winner of EHF Champions's League in 1966. They finally promoted to Handball-Bundesliga as champions of 2. Bundesliga in 2014-15 season.

Leipzig made a bid to host the 2012 Summer Olympic Games. The bid did not make the shortlist after the International Olympic Committee pared the bids down to 5.

Markkleeberg Lake (Markkleeberger See) is a new lake next to Markkleeberg, a suburb on the south side of Leipzig. A former open-pit coal mine, it was flooded in 1999 with groundwater and developed in 2006 as a tourist area. On its southeastern shore is Germany's only pump-powered artificial whitewater slalom course, Markkleeberg Canoe Park (Kanupark Markkleeberg), a venue which rivals the Eiskanal in Augsburg for training and international canoe/kayak competition.

Leipzig Rugby Club competes in the German Rugby Bundesliga but finished at the bottom of their group in 2013.[67]

Food and drink

- An all-season local dish is Leipziger Allerlei, a stew consisting of seasonal vegetables and crayfish.

- Leipziger Lerche is a shortcrust pastry dish filled with crushed almonds, nuts and strawberry jam; the name ("Leipzig lark") comes from a lark pâté which was a Leipzig speciality until the banning of songbird hunting in Saxony in 1876.

- Gose is a locally brewed top-fermenting sour beer that originated in the Goslar region and in the 18th century became popular in Leipzig.

-

Historical Gose bottle (ca. 1900)

Education

University

Leipzig University, founded 1409, is one of Europe's oldest universities. The philosopher and mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz was born in Leipzig in 1646, and attended the university from 1661 to 1666. Nobel Prize laureate Werner Heisenberg worked here as a physics professor (from 1927 to 1942), as did Nobel Prize laureates Gustav Ludwig Hertz (physics), Wilhelm Ostwald (chemistry) and Theodor Mommsen (Nobel Prize in literature). Other former staff of faculty include mineralogist Georg Agricola, writer Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, philosopher Ernst Bloch, eccentric founder of psychophysics Gustav Theodor Fechner, and psychologist Wilhelm Wundt. Among the university's many noteworthy students were writers Johann Wolfgang Goethe and Erich Kästner, and philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, political activist Karl Liebknecht, and composer Richard Wagner. Germany's chancellor since 2006, Angela Merkel, studied physics at Leipzig University.[68] The university has about 30,000 students.

A part of Leipzig University is the German Institute for Literature which was founded in 1955 under the name "Johannes R. Becher-Institut". Many noted writers have graduated from this school, including Heinz Czechowski, Kurt Drawert, Adolf Endler, Ralph Giordano, Kerstin Hensel, Sarah and Rainer Kirsch, Angela Krauß, Erich Loest, Fred Wander. After its closure in 1990 the institute was refounded in 1995 with new teachers.

Visual arts and theatre

The Academy of Visual Arts (Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst) was established in 1764. Its 530 students (as of 2006) are enrolled in courses in painting and graphics, book design/graphic design, photography and media art. The school also houses an Institute for Theory.

The University of Music and Theatre offers a broad range of subjects ranging from training in orchestral instruments, voice, interpretation, coaching, piano chamber music, orchestral conducting, choir conducting and musical composition to acting and scriptwriting.

University of Applied Science

The Leipzig University of Applied Sciences (HTWK)[69] has approximately 6,200 students (as of 2007) and is (as of 2007) the second biggest institution of higher education in Leipzig. It was founded in 1992, merging several older schools. As a university of applied sciences (German: Fachhochschule) its status is slightly below that of a university, with more emphasis on the practical part of the education. The HTWK offers many engineering courses, as well as courses in computer science, mathematics, business administration, librarianship, museum studies and social work. It is mainly located in the south of the city.

Others

The private Leipzig Graduate School of Management, (in German Handelshochschule Leipzig (HHL)), is the oldest business school in Germany.

Among the research institutes located in Leipzig, three belong to the Max Planck Society. These are the Max Planck Institute for Mathematics in the Sciences, Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences, and Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Two more are Fraunhofer Society institutes. Others are the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research, part of the Helmholtz Association of German Research Centres, and the Leibniz-Institute for Tropospheric Research.

Leipzig is home to one of the world's oldest schools Thomasschule zu Leipzig (St. Thomas' School, Leipzig), which gained fame for its long association with the Bach family of musicians and composers.

The Lutheran Theological Seminary is a seminary of the Evangelical Lutheran Free Church in Leipzig.[70][71] The seminary trains students to become pastors for the Evangelical Lutheran Free Church or for member church bodies of the Confessional Evangelical Lutheran Conference.[72]

Economy

The city is a location for automobile manufacturing by BMW and Porsche in large plants north of the city. In 2011 and 2012 DHL transferred the bulk of its European air operations from Brussels Airport to Leipzig/Halle Airport. Kirow Ardelt AG, the world market leader in breakdown cranes, is based in Leipzig. The city also houses the European Energy Exchange, the leading energy exchange in Central Europe.

Some of the largest employers in the area (outside of manufacturing) include software companies such as Spreadshirt, Unister and the various schools and universities in and around the Leipzig/Halle region. The University of Leipzig attracts millions of euros of investment yearly and is in the middle of a massive construction and refurbishment to celebrate its 600th anniversary.

Leipzig also benefits from world leading medical research (Leipzig Heart Centre) and a growing biotechnology industry.[73]

Many bars, restaurants and stores found in the downtown area are patronized by German and foreign tourists. Leipzig Hauptbahnhof itself is the location of a shopping mall.[74]

In 2010, Leipzig was included in the top 10 cities to visit by the New York Times,[54] and ranked 39th globally out of 289 cities for innovation in the 4th Innovation Cities Index published by Australian agency 2thinknow.[75] In 2015, Leipzig have among the 30 largest German cities the third best prospects for the future.[76] Leipzig is nicknamed as the "Boomtown of eastern Germany" or "Hypezig".[18][19]

Companies with operations in or around Leipzig include:

-

Porsche Diamond, the customer center building of Porsche Leipzig

-

BMW production facility in Leipzig

-

Amazon in Leipzig

-

Leipzig is the hub of DHL

-

Headquarters of the Sparkasse Leipzig bank

Media

- MDR, one of Germany's public broadcasters, has its headquarters and main television studios in the city. It provides programmes to various TV and radio networks and has its own symphony orchestra, choir and a ballet.

- Leipziger Volkszeitung (LVZ) is the city's only daily newspaper. Founded in 1894, it has published under several different forms of government. The monthly magazine Kreuzer specializes in culture, festivities and the arts in Leipzig.Leipzig was also home to the world's first daily newspaper in modern times. The "Einkommende Zeitungen" were first published in 1650.[77]

- Once known for its large number of publishing houses, Leipzig had been called Buch-Stadt (book city).,[78] the most notable of them being branches of Brockhaus and Insel Verlag. Few are left after the years of economic decline during the German Democratic Republic, during which time Frankfurt developed as a much more important publishing center. Reclam, founded in 1828, was one of the large publishing houses to move away. Leipzig still has a book fair, but Frankfurt's is far bigger.

- The German Library (Deutsche Bücherei) in Leipzig is part of Germany's National Library. Its task is to collect a copy of every book published in German.[79]

Quality of Life

In December 2013, according to a study by Marktforschungsinstituts GfK, Leipzig was ranked as the most livable city in Germany[8][80] and is one of the three European cities with the highest quality of living (after Groningen and Kraków).[81]

Transport

Road

Originally founded at the crossing of Via Regia and Via Imperii, Leipzig has been a major interchange of inter-European traffic and commerce since medieval times. After the Reunification of Germany, immense efforts to restore and expand the traffic network have been undertaken and left the city area with an excellent infrastructure.

Since 1936, Leipzig has been connected to the A 9 and A 14 autobahns via the Schkeuditzer Kreuz (Schkeuditz Cross) interchange and several exits. The A 38 completed the autobahn beltway around Leipzig in 2006.

Like most German cities, Leipzig has a traffic layout designed to be bicycle-friendly. There is an extensive cycle network. In most of the one-way central streets, cyclists are explicitly allowed to cycle both ways. A few cycle paths have been built or declared since 1990.

Rail

Leipzig Hauptbahnhof, opened in 1915, is at a junction of important north-to-south and west-to-east railway lines. The ICE train between Berlin and Munich stops in Leipzig and it takes approximately one hour from Berlin Hauptbahnhof and five hours from München Hauptbahnhof.[82]

Air

Leipzig/Halle Airport is the main airport in the vicinity of the city. Leipzig/Halle Airport offers a number of seasonal vacation charter flights as well as regular scheduled services. The former military airport near Altenburg, Thuringia called Leipzig-Altenburg Airport about a half-hour drive from Leipzig was previously (until 2010) served by Ryanair.

Water

In the first half of the 20th century, the construction of the Elster-Saale canal, White Elster and Saale was started in Leipzig in order to connect to the network of waterways. The outbreak of the Second World War stopped most of the work, though some may have continued through the use of forced labor. The Lindenauer port was almost completed but not yet connected to the Elster-Saale and Karl-Heine canal respectively. The Leipzig rivers (White Elster, New Luppe, Pleisse, and Parthe) in the city have largely artificial river beds and are supplemented by some channels. These waterways are suitable only for small leisure boat traffic.

Through the renovation and reconstruction of existing mill races and watercourses in the south of the city and flooded disused open cast mines, the city's navigable water network is being expanded. The city commissioned planning for a link between Karl Heine Canal and the disused Lindenauer port in 2008. Still more work was still scheduled to complete the Elster-Saale canal. Such a move would allow small boats to reach the Elbe from Leipzig. The intended completion date has been postponed because of an unacceptable cost-benefit ratio.

Public transport

Leipzig has an extensive local public transport network. The city's tram and bus network is operated by the Leipziger Verkehrsbetriebe. Leipzig's tram network, at a length of 148.3 km (92 miles), is the second biggest in Germany. Leipzig City Tunnel forms the centerpiece of an extensive S-Bahn network serving 1.2 million people in the Leipzig/Halle metropolitan area. The tunnel links the main station in the north with the Bayrische Bahnhof in the south.

-

Leipzig Hauptbahnhof is the main hub of tram and rail network and the world's largest railway station by floor area

-

Tram of Leipziger Verkehrsbetriebe

-

Tramsystem at the Georg-Schumann-Straße

-

Leipzig City Tunnel, part of Leipzig's new S-Bahn network

-

Train of the S-Bahn Mitteldeutschland in Leipzig-Stötteritz

Quotations

Mein Leipzig lob' ich mir! Es ist ein klein Paris und bildet seine Leute. (I praise my Leipzig! It is a small Paris and educates its people.) - Frosch, a university student in Goethe's Faust, Part One

Ich komme nach Leipzig, an den Ort, wo man die ganze Welt im Kleinen sehen kann. (I'm coming to Leipzig, to the place where one can see the whole world in miniature.) – Gotthold Ephraim Lessing

Extra Lipsiam vivere est miserrime vivere. (To live outside Leipzig is to live miserably.) - Benedikt Carpzov the Younger

Das angenehme Pleis-Athen, Behält den Ruhm vor allen, Auch allen zu gefallen, Denn es ist wunderschön. (The pleasurable Pleiss-Athens, earns its fame above all, appealing to every one, too, for it is mightily beauteous.) - Johann Sigismund Scholze

International relations

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, since 2004

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, since 2004 Birmingham, UK, since 1992[84]

Birmingham, UK, since 1992[84] Bologna, Italy, since 1962, renewed in 1997

Bologna, Italy, since 1962, renewed in 1997 Brno, Czech Republic, since 1973, renewed in 1999[85][86]

Brno, Czech Republic, since 1973, renewed in 1999[85][86] Frankfurt am Main, Germany, since 1990[87]

Frankfurt am Main, Germany, since 1990[87] Hanover, Germany, since 1987[88]

Hanover, Germany, since 1987[88] Herzliya, Israel, since 2010

Herzliya, Israel, since 2010 Houston, United States, since 1993

Houston, United States, since 1993 Kiev, Ukraine, since 1961, renewed in 1992

Kiev, Ukraine, since 1961, renewed in 1992 Kraków, Poland, since 1973, renewed in 1995[83][89][90]

Kraków, Poland, since 1973, renewed in 1995[83][89][90] Lyon, France, since 1981[91]

Lyon, France, since 1981[91] Nanjing, China, since 1988

Nanjing, China, since 1988

Thessaloniki, Greece, since 1984[92]

Thessaloniki, Greece, since 1984[92] Travnik, Bosnia and Herzegovina, since 2003

Travnik, Bosnia and Herzegovina, since 2003

See also

- Ubiquity Theatre Company - English speaking theatre projects in Leipzig.

- Leipzig Human Rights Award

- List of mayors of Leipzig

- Hugo Schneider AG

- Leipzig University Library

- Leipzig Jewish community

- Battle of Breitenfeld (1642)

References

- ↑ "Aktuelle Einwohnerzahlen nach Gemeinden 2014] (Einwohnerzahlen auf Grundlage des Zensus 2011)" (PDF). Statistisches Landesamt des Freistaates Sachsen (in German). 7 September 2015.

- 1 2 http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=urb_lpop1&lang=de

- ↑ http://www.statistik.sachsen.de/download/010_GB-Bev/Bev_Z_Gemeinde_akt.pdf

- ↑ "Shopping Tipps Leipzig :: Passagen :: Innenstadt :: Hauptbahnhof :: Informationen ::Infos :: Hinweise :: Beiträge :: Tipps :: Einkaufen". City-tourist.de. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- 1 2 Archived 3 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Business America. (27 February 1989). German Democratic Republic: long history of sustained economic growth continues. 1989 may have been an advantageous year to consider this market – Business Outlook Abroad: Current Reports from the Foreign Service.". Business America. 1989. Retrieved 2 October 2007.

- ↑ "Infrastruktur". leipzig.de.

- 1 2 FOCUS Online (11 December 2013). "Deutschlands beliebteste Städte: Sicher, sauber, grün: Diese Stadt läuft sogar München den Rang ab". FOCUS Online.

- ↑ "Zoo Leipzig: Auf Entdeckungsreise im Zoo der Zukunft". Zoo-leipzig.de. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ↑ http://www.mdr.de/sachsen/leipzig/zoo-leipzig-zweiter-platz-europa-ranking100.html

- ↑ "GaWC - The World According to GaWC 2012". lboro.ac.uk.

- ↑ http://www.welt.de/print/welt_kompakt/print_wirtschaft/article141518027/Leipzig-ist-die-Boom-Stadt-Deutschlands.html

- ↑ Hanswilhelm Haefs. Das 2. Handbuch des nutzlosen Wissens. ISBN 3-8311-3754-4 (German)

- ↑ Lexicum nominum geographicorum latinorum

- ↑ Rolf Jehke. "Stadtkreis Leipzig". territorial.de.

- ↑ ZEIT - Kann Leipzig Hypezig überleben?, 1 October 2013 (German)

- ↑ Handelsblatt - Hypezig - Leipzig mutiert zur Szenemetropole, 3 October 2013 (German)

- 1 2 http://www.mdr.de/mdr-info/geburten-in-leipzig100.html

- 1 2 dpa (3 October 2013). ""Hypezig": Leipzig mutiert zur Szenemetropole". handelsblatt.com.

- ↑ Marcel Burkhardt,. "Leipzig vs. Berlin: "Natürlich ist Leipzig das bessere Berlin"". berliner-zeitung.de.

- ↑ "Heldenstadt.de – Das Leipzig Blog! - Stadtleben, Netzwelt, Popkultur.". Heldenstadt.de - Das Leipzig Blog!.

- ↑ www.Produktiv-Crew.de. "Pleißemühlgraben: Geschichte der Fischerei". Neue-ufer.de. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ↑ "History of the cotton mill".

- ↑ Stanton, Shelby, World War II Order of Battle: An Encyclopedic Reference to U.S. Army Ground Forces from Battalion through Division, 1939-1946 (Revised Edition, 2006), Stackpole Books, p. 78, 139.

- ↑ David Brebis (ed.), Michelin guide to Germany, Greenville (2006), p. 324.

- ↑ "The day I outflanked the Stasi". BBC. 9 October 2009. + video.

- ↑ "City-Tunnel eröffnet: Leipzig rast durch die Röhre". BILD.de.

- ↑ Haase, Dagmar; Rosenberg, Matthias; Mikutta, Robert (2002-12-01). "Untersuchung zum Landschaftswandel im Südraum Leipzig". Standort (in German) 26 (4): 159–165. doi:10.1007/s00548-002-0103-3. ISSN 0174-3635.

- ↑ Ortsteilkatalog der Stadt Leipzig 2008

- ↑ "Ausgabe der Klimadaten: Monatswerte".

- ↑ LVZ-Online. "Leipzig hat wieder mehr Einwohner als Dresden - Bevölkerung in Sachsens Großstädten wächst". lvz-online.de.

- ↑ de:Einwohnerentwicklung von Leipzig#Von 1945 bis 1989

- ↑ http://www.leipzig.de/news/news/einwohner-entwicklung-uebertrifft-selbst-optimistischste-prognosen/

- ↑ http://www.statistik.sachsen.de/download/010_GB-Bev/02_03_23_tab.pdf

- ↑ "Geburten je Frau im Freistaat Sachsen 1990 2011" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ↑ http://www.statistik.sachsen.de/download/010_GB-Bev/02_03_20_tab.pdf

- ↑ "Leipzig-Informationssystem". Statistik.leipzig.de. 2012-05-18. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ↑ "Leipzig - statistik.arbeitsagentur.de". arbeitsagentur.de.

- ↑ https://www.destatis.de/DE/PresseService/Presse/Pressekonferenzen/2013/Zensus2011/bevoelkerung_zensus2011.pdf?__blob=publicationFile

- ↑ Stadt Leipzig. "Leipzig-Informationssystem > Kleinräumige Daten > Bevölkerungsbestand > Einwohner mit Migrationshintergund". leipzig.de.

- ↑ "Statistisches Jahrbuch - Aktuelle Jahrbuch-Ausgabe". Stadt Leipzig. Retrieved 2015-08-17.

- ↑ de:Liste der Plattenbausiedlungen in Sachsen#Leipzig

- ↑ de:Plattenbauten in Leipzig

- ↑ "Leipzig-Grünau". leipzig.de.

- ↑ Tallest building in Germany

- ↑ Leipzig

- ↑ "Welcome to our University of Music & Theatre". Archived from the original on 19 January 2010. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ↑ "Schulkonzerte". musikschule-leipzig.de.

- ↑ "Pop Up official website".

- ↑ "Moritzbastei homepage".

- ↑ "Tonelli's homepage" (in German). Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ↑ Neue Leipziger Schule (German Wikipedia entry)

- ↑ Lubow, Arthur (8 January 2006). "The New Leipzig School". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- 1 2 "The 31 Places to Go in 2010". The New York Times. 10 January 2010.

- ↑ "Spinnerei official website".

- ↑ "Museen at Grassi" (in German). grassimuseum.de. Archived from the original on 10 May 2015.

- ↑ "Institut für Klassische Archäologie und Antikenmuseum" (in German).

- ↑ "AMI - Auto Mobil International, Leipziger Messe". Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ↑ "AMITEC - Fachmesse für Fahrzeugteile, Werkstatt und Service, Leipziger Messe". Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ↑ "Jazzclug-leipzig.de homepage".

- ↑ "Ladyfest Leipzigerinnen homepage".

- ↑ "Oper Unplugger - Musik Tanz Theater" (in German). Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ↑ "Leipzig Pop Up independent music trade fair and festival". Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ↑ "Das Leipziger Sportangebot aktuell" (in German). leipzig.de. Archived from the original on 28 February 2008. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ↑ Ruf, Christoph (19 June 2009). "Buying Its Way to the Bundesliga - Red Bull Wants to Caffeinate Small football Club". Spiegel Online International. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ↑ Fritz Rudolph. "Was einst mit dem Krummstab begann ... Zur Geschichte des Eishockeysports in der Region Leipzig". sportmuseum-leipzig.de. Archived from the original on 15 January 2010. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ↑ "Rugby Club Leipzig e.V.". leipzig-rugby.de.

- ↑ "Leipzig University homepage".

- ↑ "?". Archived from the original on 21 March 2015.

- ↑ "Lutherisches Theologisches Seminar".

- ↑ "Lutherisches Theologisches Seminar Leipzig".

- ↑ "Evangelical Lutheran Free Church - Germany".

- ↑ Stephan Gasteyger. "Discover Leipzig". Berlin Things to Do.

- ↑ "Promenaden Hauptbahnhof Leipzig".

- ↑ Date: 1 September 2010 (2010-09-01). "Innovation Cities Global Index 2010 " Innovation Cities Program & Index: Creating Innovative Cities: USA, Canada, Europe, Latin America, Asia, Australia". Innovation-cities.com. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ↑ http://www.berliner-zeitung.de/berlin/lebensqualitaet-in-der-hauptstadt-berlin-erobert-platz-2-im-staedteranking,10809148,32229294.html

- ↑ de:Einkommende Zeitungen

- ↑ "Homepage of the City of Leipzig/Buchstadt". Archived from the original on 23 May 2013.

- ↑ German National Library

- ↑ "Deutschlands beliebteste Städte: Leipzig im Ranking ganz vorne - N24.de". N24.de. 9 December 2013.

- ↑ "Lebensqualität: Leipzig ist die beste deutsche Stadt Europas - DIE WELT". DIE WELT. 26 July 2007.

- ↑ "Home" (in German). Deutsche Bahn. Archived from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- 1 2 "Leipzig - International Relations". Referat Internationale Zusammenarbeit, City of Leipzig. Retrieved 2015-01-29.

- ↑ "Partner Cities". Birmingham City Council. Archived from the original on 15 September 2009. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- ↑ "City of Brno Foreign Relations - Statutory city of Brno" (in Czech). 2003 City of Brno. Retrieved 6 September 2011. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Brno - Partnerská města" (in Czech). © 2006-2009 City of Brno. Retrieved 17 July 2009. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Frankfurt -Partner Cities". © 2008 Stadt Frankfurt am Main. Retrieved 5 December 2008. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Hanover - Twin Towns" (in German). © 2007-2009 HANNOVER.de - Offizielles Portal der Landeshauptstadt und der Region Hannover in Zusammenarbeit mit hier.de. Archived from the original on 27 June 2009. Retrieved 17 July 2009. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Leipzig - International Relations". © 2009 Leipzig City Council, Office for European and International Affairs. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- ↑ "Kraków - Miasta Partnerskie" [Kraków -Partnership Cities]. Miejska Platforma Internetowa Magiczny Kraków (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2013-07-02. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- ↑ "Partner Cities of Lyon and Greater Lyon". © 2008 Mairie de Lyon. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- ↑ "Twinning Cities". City of Thessaloniki. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Leipzig. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Leipzig. |

- The city's official website

- Leipzig at DMOZ

- Leipzig as virtual city 408 Points of Interest - English

- Ubiquity Theatre Company, - English language theatre projects in Leipzig

- Leipzig Zeitgeist, an English magazine about Leipzig

- This is Leipzig, an English web site for Leipzig

- Events in Leipzig Music Festivals in Leipzig

Leipzig travel guide from Wikivoyage

Leipzig travel guide from Wikivoyage "Leipsic". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

"Leipsic". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

|

Halle | Delitzsch, Dessau | Berlin |  |

| Kassel | |

Dresden | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Jena, Weimar, Erfurt | Gera, Zwickau | Chemnitz |

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||

|