Le Corbusier

| Le Corbusier | |

|---|---|

|

Le Corbusier in 1933 | |

| Born |

Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris October 6, 1887 La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland |

| Died |

August 27, 1965 (aged 77) Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, France |

| Nationality | Swiss, French |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Awards | AIA Gold Medal (1961) |

| Buildings |

Villa Savoye, Poissy Villa La Roche, Paris Unité d'habitation, Marseille Notre Dame du Haut, Ronchamp Buildings in Chandigarh, India |

| Projects | Ville radieuse |

| Signature | |

|

| |

Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris, who was better known as Le Corbusier (French: [lə kɔʁbyzje]; October 6, 1887 – August 27, 1965), was a Swiss-French architect, designer, painter, urban planner, writer, and one of the pioneers of what is now called modern architecture. He was born in Switzerland and became a French citizen in 1930. His career spanned five decades, with his buildings constructed throughout Europe, India, and the Americas.

Dedicated to providing better living conditions for the residents of crowded cities, Le Corbusier was influential in urban planning, and was a founding member of the Congrès international d'architecture moderne (CIAM). Corbusier prepared the master plan for the city of Chandigarh in India, and contributed specific designs for several buildings there.

Early life and education, 1887–1914

%2C_1920%2C_Still_Life%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_80.9_x_99.7_cm%2C_Museum_of_Modern_Art.jpg)

He was born as Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris in La Chaux-de-Fonds, a small city in Neuchâtel canton in north-western Switzerland, in the Jura mountains, just 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) across the border from France. He attended a kindergarten that used Fröbelian methods.

Young Jeanneret was attracted to the visual arts and studied at the La-Chaux-de-Fonds Art School under Charles L'Eplattenier, who had studied in Budapest and Paris. His architecture teacher in the Art School was the architect René Chapallaz, who had a large influence on Le Corbusier's earliest house designs.

In his early years he would frequently escape the somewhat provincial atmosphere of his hometown by traveling around Europe. In September 1907, he made his first trip outside of Switzerland, going to Italy; then that winter traveling through Budapest to Vienna, where he would stay for four months and meet Gustav Klimt and Josef Hoffman.[1] At around 1908, he traveled to Paris, where he found work in the office of Auguste Perret, the French pioneer of reinforced concrete. It was both his trip to Italy and his employment at Perret's office that began to form his own ideas about architecture. Between October 1910 and March 1911, he worked near Berlin for the renowned architect Peter Behrens, where he may have met Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius. He became fluent in German. More than anything during this period, it was his visit to the Charterhouse of the Valley of Ema that influenced his architectural philosophy profoundly for the rest of his life. He believed that all people should have the opportunity to live as beautifully and peacefully as the monks he witnessed in the sanctuaries at the charterhouse.

%2C_1922%2C_Nature_morte_verticale_(Vertical_Still_Life)%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_146.3_x_89.3_cm%2C_Kunstmuseum%2C_Basel.jpg)

Later in 1911, he journeyed to the Balkans and visited Serbia, Bulgaria, Turkey, and Greece, filling nearly 80 sketchbooks with renderings of what he saw—including many sketches of the Parthenon, whose forms he would later praise in his work Vers une architecture (1923) ("Towards an Architecture", but usually translated into English as "Towards a New Architecture"). A fresh translation of "Toward an Architecture"[2] was published in 2007 by the Getty Research Institute, with an introduction by French architect and architectural historian Jean-Louis Cohen, who spoke about the translation.[3]

Early career: The villas, 1914–1920

During World War I, Le Corbusier taught at his old school in La-Chaux-de-Fonds, not returning to Paris until the war was over. During these four years in Switzerland, he worked on theoretical architectural studies using modern techniques.[4] Among these was his project for the Dom-Ino House (1914–15). This model proposed an open floor plan consisting of concrete slabs supported by a minimal number of thin reinforced concrete columns around the edges, with a stairway providing access to each level on one side of the floor plan.

This design became the foundation for most of his architecture over the next ten years. Soon he began his own architectural practice with his cousin, Pierre Jeanneret (1896–1967), a partnership that would last until the 1950s, with an interruption in the World War II years, because of Le Corbusier's ambivalent position towards the Vichy regime.

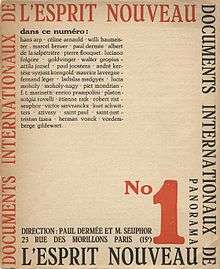

In 1918, Le Corbusier met the Cubist painter Amédée Ozenfant, in whom he recognised a kindred spirit. Ozenfant encouraged him to paint, and the two began a period of collaboration. Rejecting Cubism as irrational and "romantic", the pair jointly published their manifesto, Après le cubisme and established a new artistic movement, Purism. Ozenfant and Le Corbusier established the Purist journal L'Esprit nouveau. He was good friends with the Cubist artist Fernand Léger.

Pseudonym adopted, 1920

%2C_1920%2C_Guitare_verticale_(2%C3%A8me_version)%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_100_x_81_cm%2C_Fondation_Le_Corbusier%2C_Paris.jpg)

In the first issue of the journal, in 1920, Charles-Edouard Jeanneret adopted Le Corbusier (an altered form of his maternal grandfather's name, Lecorbésier) as a pseudonym, reflecting his belief that anyone could reinvent themselves. Adopting a single name to identify oneself was in vogue by artists in many fields during that era, especially in Paris.

Between 1918 and 1922, Le Corbusier did not build anything, concentrating his efforts on Purist theory and painting. In 1922, he and his cousin Pierre Jeanneret opened a studio in Paris at 35 rue de Sèvres.[4]

His theoretical studies soon advanced into several different single-family house models. Among these was the Maison "Citrohan", a pun on the name of the French Citroën automaker, for the modern industrial methods and materials Le Corbusier advocated using for the house. Here, Le Corbusier proposed a three-floor structure, with a double-height living room, bedrooms on the second floor, and a kitchen on the third floor. The roof would be occupied by a sun terrace. On the exterior Le Corbusier installed a stairway to provide second-floor access from ground level. Here, as in other projects from this period, he also designed the facades to include large uninterrupted banks of windows. The house used a rectangular plan, with exterior walls that were not filled by windows but left as white, stuccoed spaces. Le Corbusier and Jeanneret left the interior aesthetically spare, with any movable furniture made of tubular metal frames. Light fixtures usually comprised single, bare bulbs. Interior walls also were left white. Between 1922 and 1927, Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret designed many of these private houses for clients around Paris. In Boulogne-sur-Seine and the 16th arrondissement of Paris, Le Corbusier and Jeanneret designed and built the Villa Lipschitz, Maison Cook, Maison Planeix, and the Maison La Roche/Albert Jeanneret, which now houses the Fondation Le Corbusier.

Relationship with the USSR

Le Corbusier had a short relationship with the Soviet Union, starting with his first trip to Moscow in 1928, and ending with the rejection of his proposal for the Palace of the Soviets in 1932.

Personal life

While returning in 1929 from South America to Europe, Le Corbusier met entertainer and actress Josephine Baker on board the ocean liner Lutétia. Le Corbusier made several nude sketches of Baker. Soon after his return to France, Le Corbusier married Yvonne Gallis, a dressmaker and fashion model. She died in 1957. Le Corbusier also had a long extramarital affair with Swedish-American heiress Marguerite Tjader Harris.

Le Corbusier became a French citizen in 1930.[4]

Urbanism

For a number of years, French officials had been unsuccessful in dealing with the squalor of the growing Parisian slums, and Le Corbusier sought efficient ways to house large numbers of people in response to the urban housing crisis. He believed that his new, modern architectural forms would provide an organizational solution that would raise the quality of life for the lower classes. His Immeubles Villas (1922) was such a project, calling for large blocks of cell-like individual apartments stacked one on top of one another, with plans that included a living room, bedrooms, and kitchen, as well as a garden terrace.

Not merely content with designs for a few housing blocks, Le Corbusier soon moved into studies for entire cities. In 1922 he presented his scheme for a "Contemporary City" for three million inhabitants (Ville Contemporaine). The centerpiece of this plan was the group of sixty-story cruciform skyscrapers, steel-framed office buildings encased in huge curtain walls of glass. Referred to as towers in a park, these skyscrapers were set within large, rectangular, park-like green spaces. At the center was a huge transportation hub that on different levels included depots for buses and trains, as well as highway intersections, and at the top, an airport. Le Corbusier had the fanciful notion that commercial airliners would land between the huge skyscrapers. He segregated pedestrian circulation paths from the roadways and glorified the automobile as a means of transportation. As one moved out from the central skyscrapers, smaller low-story, zig-zag apartment blocks (set far back from the street amid green space) housed the inhabitants. Le Corbusier hoped that politically minded industrialists in France would lead the way with their efficient Taylorist and Fordist strategies adopted from American industrial models to reorganize society. As Norma Evenson has put it, "the proposed city appeared to some an audacious and compelling vision of a brave new world, and to others a frigid megalomaniacally scaled negation of the familiar urban ambient."[5]

In this new industrial spirit, Le Corbusier contributed to a new journal called L'Esprit Nouveau that advocated the use of modern industrial techniques and strategies to transform society into a more efficient environment with a higher standard of living on all socioeconomic levels. He forcefully argued that this transformation was necessary to avoid the spectre of revolution that would otherwise shake society. His dictum "Architecture or Revolution", developed in his articles in this journal, became his rallying cry for the book Vers une architecture (Toward an Architecture, previously mistranslated into English as Towards a New Architecture), which comprised selected articles he contributed to L'Esprit Nouveau between 1920 and 1923. In this book, Le Corbusier followed the influence of Walter Gropius and reprinted several photographs of North American factories and grain elevators.[6]

Theoretical urban schemes continued to occupy Le Corbusier. He exhibited his "Plan Voisin", sponsored by an automobile manufacturer, in 1925. In it, he proposed to bulldoze most of central Paris north of the Seine and replace it with his sixty-story cruciform towers from the Contemporary City, placed within an orthogonal street grid and park-like green space. His scheme was met with criticism and scorn from French politicians and industrialists, although they were favorable to the ideas of Taylorism and Fordism underlying his designs. Nonetheless, it did provoke discussion concerning how to deal with the cramped, dirty conditions that enveloped much of the city.

In the 1930s, Le Corbusier expanded and reformulated his ideas on urbanism, eventually publishing them in La Ville radieuse (The Radiant City) in 1935. Perhaps the most significant difference between the Contemporary City and the Radiant City is that the latter abandoned the class-based stratification of the former; housing was now assigned according to family size, not economic position.[7] Some have read dark overtones into The Radiant City: from the "astonishingly beautiful assemblage of buildings" that was Stockholm, for example, Le Corbusier saw only "frightening chaos and saddening monotony." He dreamed of "cleaning and purging" the city, bringing "a calm and powerful architecture"—referring to steel, plate glass, and reinforced concrete. Although Le Corbusier's designs for Stockholm did not succeed, later architects took his ideas and partly "destroyed" the city with them.[8]

La Ville radieuse also marks Le Corbusier's increasing dissatisfaction with capitalism and his turn to the right-wing syndicalism of Hubert Lagardelle. During the Vichy regime, Le Corbusier received a position on a planning committee and made designs for Algiers and other cities. The central government ultimately rejected his plans, and after 1942 Le Corbusier left Vichy for Paris.[9] There he became a technical adviser at Alexis Carrel's eugenic foundation, from which he only resigned on April 20, 1944.[10]

After World War II, Le Corbusier attempted to realize his urban planning schemes on a small scale by constructing a series of "unités" (the housing block unit of the Radiant City) around France. The most famous of these was the Unité d'Habitation of Marseille (1946–52). In the 1950s, a unique opportunity to translate the Radiant City on a grand scale presented itself in the construction of the Union Territory Chandigarh, the new capital for the Indian states of Punjab and Haryana and India's first planned city. Le Corbusier designed many administration buildings, including a courthouse, parliament building, and a university. He also designed the general layout of the city, dividing it into sectors. Le Corbusier was brought on to develop the plan of Albert Mayer.

Death

Against his doctor's orders, on August 27, 1965, Le Corbusier went for a swim in the Mediterranean Sea at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, France. His body was found by bathers and he was pronounced dead at 11 a.m. It was assumed that he may have suffered a heart attack. His funeral took place in the courtyard of the Louvre Palace on September 1, 1965, under the direction of writer and thinker André Malraux, who was at the time France's Minister of Culture. He was buried alongside his wife in the grave he had designated at Roquebrune.

Le Corbusier's death had a strong impact on the cultural and political world. Tributes poured in from around the world, even from some of Le Corbusier's strongest artistic critics. Painter Salvador Dalí recognised his importance and sent a floral tribute. United States President Lyndon B. Johnson said, "His influence was universal and his works are invested with a permanent quality possessed by those of very few artists in our history." The Soviet Union added, "Modern architecture has lost its greatest master". While his funeral occurred in Paris, Japanese TV channels broadcast his Museum in Tokyo in what was at the time a unique media homage.

His grave is in the cemetery above Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, between Menton and Monaco in southern France.

The Fondation Le Corbusier (FLC) functions as his official estate.[11] The U.S. copyright representative for the Fondation Le Corbusier is the Artists Rights Society.[12]

Ideas

Five points of architecture

It was Le Corbusier's Villa Savoye (1929–31) that most succinctly summed up the five points of architecture that he had elucidated in L'Esprit Nouveau and the book Vers une architecture, which he had been developing throughout the 1920s. First, Le Corbusier lifted the bulk of the structure off the ground, supporting it by pilotis, reinforced concrete stilts. These pilotis, in providing the structural support for the house, allowed him to elucidate his next two points: a free facade, meaning non-supporting walls that could be designed as the architect wished, and an open floor plan, meaning that the floor space was free to be configured into rooms without concern for supporting walls. The second floor of the Villa Savoye includes long strips of ribbon windows that allow unencumbered views of the large surrounding garden, and which constitute the fourth point of his system. The fifth point was the roof garden to compensate for the green area consumed by the building and replacing it on the roof. A ramp rising from ground level to the third-floor roof terrace allows for an architectural promenade through the structure. The white tubular railing recalls the industrial "ocean-liner" aesthetic that Le Corbusier much admired.

Modulor

Le Corbusier explicitly used the golden ratio in his Modulor system for the scale of architectural proportion. He saw this system as a continuation of the long tradition of Vitruvius, Leonardo da Vinci's "Vitruvian Man", the work of Leon Battista Alberti, and others who used the proportions of the human body to improve the appearance and function of architecture. In addition to the golden ratio, Le Corbusier based the system on human measurements, Fibonacci numbers, and the double unit.

He took Leonardo's suggestion of the golden ratio in human proportions to an extreme: he sectioned his model human body's height at the navel with the two sections in golden ratio, then subdivided those sections in golden ratio at the knees and throat; he used these golden ratio proportions in the Modulor system.

Le Corbusier's 1927 Villa Stein in Garches exemplified the Modulor system's application. The villa's rectangular ground plan, elevation, and inner structure closely approximate golden rectangles.[13]

Le Corbusier placed systems of harmony and proportion at the centre of his design philosophy, and his faith in the mathematical order of the universe was closely bound to the golden section and the Fibonacci series, which he described as "rhythms apparent to the eye and clear in their relations with one another. And these rhythms are at the very root of human activities. They resound in Man by an organic inevitability, the same fine inevitability which causes the tracing out of the Golden Section by children, old men, savages, and the learned."[14]

Open Hand

The Open Hand (La Main Ouverte) is a recurring motif in Le Corbusier's architecture, a sign for him of "peace and reconciliation. It is open to give and open to receive." The largest of the many Open Hand sculptures that Le Corbusier created is a 26 meter high version in Chandigarh, India known as Open Hand Monument.

Furniture

Corbusier said: "Chairs are architecture, sofas are bourgeois".

Le Corbusier began experimenting with furniture design in 1928 after inviting the architect, Charlotte Perriand, to join his studio. His cousin, Pierre Jeanneret, also collaborated on many of the designs. Before the arrival of Perriand, Le Corbusier relied on ready-made furniture to furnish his projects, such as the simple pieces manufactured by Thonet, the company that manufactured his designs in the 1930s.

In 1928, Le Corbusier and Perriand began to put the expectations for furniture Le Corbusier outlined in his 1925 book L'Art Décoratif d'aujourd'hui into practice. In the book he defined three different furniture types: type-needs, type-furniture, and human-limb objects. He defined human-limb objects as: "Extensions of our limbs and adapted to human functions that are type-needs and type-functions, therefore type-objects and type-furniture. The human-limb object is a docile servant. A good servant is discreet and self-effacing in order to leave his master free. Certainly, works of art are tools, beautiful tools. And long live the good taste manifested by choice, subtlety, proportion, and harmony".

The first results of the collaboration were three chrome-plated tubular steel chairs designed for two of his projects, The Maison la Roche in Paris and a pavilion for Barbara and Henry Church. The line of furniture was expanded for Le Corbusier's 1929 Salon d'Automne installation, 'Equipment for the Home'.

These chairs included the LC-1, LC-2, LC-3, and LC-4, originally entitled "Basculant" (LC-1), "Fauteuil grand confort, petit modèle" (LC-2, "great comfort sofa, small model"), "Fauteuil grand confort, grand modèle" (LC-3, "great comfort sofa, large model"), and "Chaise longue" (LC-4, "Long chair").[15] The LC-2 and LC-3 are more colloquially referred to as the petit confort and grand confort (abbreviation of full title, and due to respective sizes). The LC-2 (and similar LC-3) have been featured in a variety of media, notably the Maxell "blown away" advertisement.[16]

In the year 1964, while Le Corbusier was still alive, Cassina S.p.A. of Milan acquired the exclusive worldwide rights to manufacture his furniture designs. Today many copies exist, but Cassina is still the only manufacturer authorized by the Fondation Le Corbusier; see US page. Today, some productions of the original furniture designs are considered very valuable to art collectors and are often sold in major auction houses.

Politics

In the 1930s, Le Corbusier associated with the Faisceau of Georges Valois and Hubert Lagardelle and briefly edited the syndicalist journals Plans and Prélude. In 1934, he lectured in Rome on architecture, by invitation of Benito Mussolini. He sought out a position in urban planning in the Vichy regime and received an appointment on a committee studying urbanism. He drew up plans for the redesign of Algiers in which he criticized the perceived differences in living standards between Europeans and Africans in the city, describing a situation in which "the civilised live like rats in holes" yet "the barbarians live in solitude, in well-being."[17] These and plans for the redesign of other cities were ultimately ignored. After this defeat, Le Corbusier largely eschewed politics.

Although the politics of Lagardelle and Valois included elements of fascism, anti-semitism, and ultra-nationalism, Le Corbusier's own affiliation with these movements remains uncertain. In La Ville radieuse, he conceives an essentially apolitical society, in which the bureaucracy of economic administration effectively replaces the state.[18]

Le Corbusier was heavily indebted to the thought of the 19th-century French utopians Saint-Simon and Charles Fourier. There is a noteworthy resemblance between the concept of the unité and Fourier's phalanstery.[19] From Fourier, Le Corbusier adopted at least in part his notion of administrative, rather than political, government.

Criticism

Since his death, Le Corbusier's contribution has been hotly contested, as the architecture values and its accompanying aspects within modern architecture vary, both between different schools of thought and among practising architects.[20] At the level of building, his later works expressed a complex understanding of modernity's impact, yet his urban designs have drawn scorn from critics.

Technological historian and architecture critic Lewis Mumford wrote in Yesterday's City of Tomorrow that the extravagant heights of Le Corbusier's skyscrapers had no reason for existence apart from the fact that they had become technological possibilities. The open spaces in his central areas had no reason for existence either, Mumford wrote, since on the scale he imagined there was no motive during the business day for pedestrian circulation in the office quarter. By "mating utilitarian and financial image of the skyscraper city to the romantic image of the organic environment, Le Corbusier had, in fact, produced a sterile hybrid."

The public housing projects influenced by his ideas are seen by some as having had the effect of isolating poor communities in monolithic high-rises and breaking the social ties integral to a community's development. One of his most influential detractors has been Jane Jacobs, who delivered a scathing critique of Le Corbusier's urban design theories in her seminal work The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

Influence

Le Corbusier was at his most influential in the sphere of urban planning, and was a founding member of the Congrès International d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM). One of the first to realize how the automobile would change human agglomerations, Le Corbusier described the city of the future as consisting of large apartment buildings isolated in a park-like setting on pilotis. Le Corbusier's theories were adopted by the builders of public housing in Europe and the United States. In Great Britain urban planners turned to Le Corbusier's "Cities in the Sky" as a cheaper method of providing public housing from the late 1950s.[21] For the design of the buildings themselves, Le Corbusier criticized any effort at ornamentation. The large spartan structures in cities, but not 'of' cities, have been widely criticized for being boring and unfriendly to pedestrians.

Throughout the years, many architects worked for Le Corbusier in his studio, and a number of them became notable in their own right, including painter-architect Nadir Afonso, who absorbed Le Corbusier's ideas into his own aesthetics theory. Lúcio Costa's city plan of Brasília and the industrial city of Zlín planned by František Lydie Gahura in the Czech Republic are notable plans based on his ideas, while the architect himself produced the plan for Chandigarh in India. Le Corbusier's thinking also had profound effects on the philosophy of city planning and architecture in the Soviet Union, particularly in the Constructivist era.

Le Corbusier was heavily influenced by problems he saw in industrial cities at the turn of the 20th century. He thought that industrial housing techniques led to crowding, dirtiness, and a lack of a moral landscape. He was a leader of the modernist movement to create better living conditions and a better society through housing concepts. Ebenezer Howard's Garden Cities of Tomorrow heavily influenced Le Corbusier and his contemporaries.

Le Corbusier also harmonized and lent credence to the idea of space as a set of destinations which mankind moved between, more or less continuously. He was therefore able to give credence and credibility to the automobile (as a transporter); and most importantly to freeways in urban spaces. His philosophies were useful to urban real estate development interests in the American Post World War II period because they justified and lent architectural and intellectual support to the desire to destroy traditional urban space for high density high profit urban concentration, both commercial and residential. Le Corbusier's ideas also sanctioned further destruction of traditional urban spaces to build freeways that connected this new urbanism to low density, low cost (and highly profitable), suburban and rural locales which were free to be developed as middle class single-family (dormitory) housing.

Notably missing from this scheme of movement were connectivity between isolated urban villages created for lower-middle and working classes and other destination points in Le Corbusier's plan: suburban and rural areas, and urban commercial centers. This was because, as designed, the freeways traveled over, at, or beneath grade levels of the living spaces of the urban poor (one modern example: the Cabrini–Green housing project in Chicago). Such projects and their areas, having no freeway exit ramps, cut off by freeway rights-of-way, became isolated from jobs and services concentrated at Le Corbusier's nodal transportation end points. As jobs increasingly moved to the suburban end points of the freeways, urban village dwellers found themselves without convenient freeway access points in their communities and without public mass transit connectivity that could economically reach suburban job centers. Very late in the Post-War period, suburban job centers found this to be such a critical problem (labor shortages) that they, on their own, began sponsoring urban-to-suburban shuttle bus services between urban villages and suburban job centers, to fill working class and lower-middle class jobs which had gone wanting, and which did not normally pay the wages that car ownership required.

Le Corbusier had a great influence on architects and urbanists all the world. In the United States, Shadrach Woods; in Spain, Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza; in Brazil, Oscar Niemeyer; In Mexico, Mario Pani Darqui; in Chile, Roberto Matta; in Argentina, Antoni Bonet i Castellana (a Catalan exile), Juan Kurchan, Jorge Ferrari Hardoy, Amancio Williams, and Clorindo Testa in his first era; in Uruguay, the professors Justino Serralta and Carlos Gómez Gavazzo; in Colombia, Germán Samper Gnecco, Rogelio Salmona, and Dicken Castro; in Peru, Abel Hurtado and José Carlos Ortecho.

Fondation Le Corbusier

The Fondation Le Corbusier is a private foundation and archive honoring the work of architect Le Corbusier (1887–1965). It operates Maison La Roche, a museum located in the 16th arrondissement at 8–10, square du Dr Blanche, Paris, France, which is open daily except Sunday.

The Fondation Le Corbusier was established in 1968. It now owns Maison La Roche and Maison Jeanneret (which form the foundation's headquarters), as well as the apartment occupied by Le Corbusier from 1933 to 1965 at rue Nungesser et Coli in Paris 16e, and the "Small House" he built for his parents in Corseaux on the shores of Lac Leman (1924).

Maison La Roche and Maison Jeanneret (1923–24), also known as the La Roche-Jeanneret house, is a pair of semi-detached houses that was Corbusier's third commission in Paris. They are laid out at right angles to each other, with iron, concrete, and blank, white facades setting off a curved two-story gallery space. Maison La Roche is now a museum containing about 8,000 original drawings, studies and plans by Le Corbusier (in collaboration with Pierre Jeanneret from 1922 to 1940), as well as about 450 of his paintings, about 30 enamels, about 200 other works on paper, and a sizable collection of written and photographic archives. It describes itself as the world's largest collection of Le Corbusier drawings, studies, and plans.[11][22]

Awards

He received the Frank P. Brown Medal and AIA Gold Medal in 1961. The University of Cambridge awarded Le Corbusier an honorary degree in June 1959.[23]

Memorials

Le Corbusier's portrait was featured on the 10 Swiss francs banknote, pictured with his distinctive eyeglasses.

The following place-names carry his name:

- Place Le Corbusier, Paris, near the site of his atelier on the Rue de Sèvres.

- Le Corbusier Boulevard, Laval, Quebec, Canada.

- Place Le Corbusier in his hometown of La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland.

- Le Corbusier Street in the partido of Malvinas Argentinas, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina.

- Le Corbusier Street in Le Village Parisien of Brossard, Quebec, Canada.

- Le Corbusier Promenade, a promenade along the water at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin.

- Le Corbusier Museum, Sector- 19 Chandigarh, India.

- Le Corbusier Museum in Stuttgart am Weissenhof

Works

- 1923: Villa La Roche, Paris

- 1925: Villa Jeanneret, Paris

- 1928: Villa Savoye, Poissy-sur-Seine, France

- 1929: Cité du Refuge, Armée du Salut, Paris, France

- 1931: Palace of the Soviets, Moscow, USSR (project)

- 1931: Immeuble Clarté, Geneva, Switzerland

- 1933: Tsentrosoyuz, Moscow, USSR

- 1947–1952: Unité d'Habitation, Marseille, France

- 1949–1952: United Nations headquarters, New York City (Consultant)

- 1949–1953: Curutchet House, La Plata, Argentina (project manager: Amancio Williams )

- 1950–1954: Chapelle Notre Dame du Haut, Ronchamp, France

- 1951: Maisons Jaoul, Neuilly-sur-Seine, France

- 1951: Buildings in Ahmedabad, India

- 1951: Sanskar Kendra Museum, Ahmedabad

- 1951: ATMA House

- 1951: Villa Sarabhai, Ahmedabad

- 1951: Villa Shodhan, Ahmedabad

- 1952: Unité d'Habitation of Nantes-Rezé, Nantes, France

- 1952–1959: Buildings in Chandigarh, India

- 1952: Palace of Justice

- 1952: Museum and Gallery of Art

- 1953: Secretariat Building

- 1953: Governor's Palace

- 1955: Palace of Assembly

- 1959: Government College of Art (GCA) and the Chandigarh College of Architecture(CCA)

- 1957: Maison du Brésil, Cité Universitaire, Paris

- 1957–1960: Sainte Marie de La Tourette, near Lyon, France (with Iannis Xenakis)

- 1957: Unité d'Habitation of Berlin-Charlottenburg, Flatowallee 16, Berlin

- 1962: Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts at Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts

- 1964–1969: Firminy-Vert

- 1964: Unité d'Habitation of Firminy, France

- 1965: Maison de la culture de Firminy-Vert

- 1967: Heidi Weber Museum (Centre Le Corbusier), Zurich, Switzerland

Bibliography

- 1918: Après le cubisme (After Cubism), with Amédée Ozenfant

- 1923: Vers une architecture (Towards an Architecture) (frequently mistranslated as "Towards a New Architecture")

- 1925: Urbanisme (Urbanism)

- 1925: La Peinture moderne (Modern Painting), with Amédée Ozenfant

- 1925: L'Art décoratif d'aujourd'hui (The Decorative Arts of Today)

- 1931: Premier clavier de couleurs (First Color Keyboard)

- 1935: Aircraft

- 1935: La Ville radieuse (The Radiant City)

- 1942: Charte d'Athènes (Athens Charter)

- 1943: Entretien avec les étudiants des écoles d'architecture (A Conversation with Architecture Students)

- 1945: Les Trois établissements Humains (The Three Human Establishments)

- 1948: Le Modulor (The Modulor)

- 1953: Le Poeme de l'Angle Droit (The Poem of the Right Angle)

- 1955: Le Modulor 2 (The Modulor 2)

- 1959: Deuxième clavier de couleurs (Second Colour Keyboard)

- 1966: Le Voyage d'Orient (The Voyage to the East)

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Foundation Le Corbusier". http://www.fondationlecorbusier.fr/corbuweb/morpheus.aspx?sysId=15&IrisObjectId=6943&sysLanguage=en-en&itemPos=1&sysParentId=15&clearQuery=1. External link in

|website=(help); - ↑ Le Corbusier: Toward an Architecture. The Getty Research Institute. ISBN 978-0-89236-822-8.

- ↑ "Jean Louis Cohen on Toward and Architecture". http://www.getty.edu/research/videos/jlcohen_video.html. External link in

|website=(help); - 1 2 3 Choay, Françoise (1960). Le Corbusier. George Braziller, Inc. pp. 10–11. ISBN 0-8076-0104-7. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Evenson, Norma (1969). Le Corbusier: The Machine and the Grand Design. New York: George Braziller. p. 7.

- ↑ "American Colossus: the Grain Elevator 1843–1943". Colossus Books. 11 January 2013. ISBN 978-0578012612.

- ↑ Fishman, Robert (1982). Urban Utopias in the Twentieth Century: Ebenezer Howard, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Le Corbusier. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. p. 231. Retrieved 2014-03-18.

- ↑ Dalrymple, Theodore (Autumn 2009). "The Architect as Totalitarian: Le Corbusier’s baleful influence". City Journal 19 (4). Retrieved 2014-03-18.

- ↑ Fishman 1982, pp. 244–246.

- ↑ "Le Corbusier plus facho que fada". Liberation. 18 March 2015. Retrieved 2015-03-23.

- 1 2 "Foundation: History". Fondation Le Corbusier. Retrieved 2014-03-18.

- ↑ "Our Most Frequently Requested Prominent Artists". Artists Rights Society. 2003. Retrieved 2014-03-18.

- ↑ Padovan, Richard (2 November 1999). Proportion: Science, Philosophy, Architecture. Taylor & Francis. p. 320. ISBN 0-419-22780-6.

from Le Corbusier, The Modulor p.35: "Both the paintings and the architectural designs make use of the golden section."

- ↑ padovan 1999, p. 316.

- ↑ "Le Corbusier Classics LC2, LC3 and LC4 Get Colorful, Courtesy Of Cassina". ifitshipitshere.blogspot.com. 27 July 2010. Retrieved 2014-03-18.

- ↑ Hannibal, John (17 October 2012). "The iconic Maxell tape advertisement". AV Adviser. Retrieved 2014-03-18.

- ↑ Celik, Zeynep (28 July 1997). Urban Forms and Colonial Confrontations: Algiers under French Rule. University of California Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0520204577. Retrieved 2014-03-18.

- ↑ Fishman 1982, p. 228.

- ↑ Serenyi, Peter (December 1967). "Le Corbusier, Fourier, and the Monastery of Ema". The Art Bulletin 49 (4): 282. doi:10.2307/3048487.

- ↑ Holm, Ivar (2006). Ideas and Beliefs in Architecture and Industrial design: How attitudes, orientations, and underlying assumptions shape the build environment. Oslo School of Architecture and Design. ISBN 82-547-0174-1.

- ↑ http://www.pash-living.co.uk/blog/contemporary-designers/le-corbusier-enfant-terrible-of-modernist-architecture.html

- ↑ "Musée: Fondation Le Corbusier - Maison La Roche". Paris Convention and Visitors Bureau. Retrieved 2014-03-18.

- ↑ "About the Faculty". University of Cambridge. Retrieved 2014-03-18.

References

- Sarbjit Bahga, Surinder Bahga (2014) Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret: The Indian Architecture, CreateSpace, ISBN 978-1495906251

- Behrens, Roy R. (2005). Cook Book: Gertrude Stein, William Cook and Le Corbusier. Dysart, Iowa: Bobolink Books. ISBN 0-9713244-1-7.

- Brooks, H. Allen (1999) Le Corbusier's Formative Years: Charles-Edouard Jeanneret at La Chaux-de-Fonds, Paperback Edition, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-07582-6

- Eliel, Carol S. (2002). L'Esprit Nouveau: Purism in Paris, 1918 – 1925. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 0-8109-6727-8

- Curtis, William J.R. (1994) Le Corbusier: Ideas and Forms, Phaidon, ISBN 978-0-7148-2790-2

- Frampton, Kenneth. (2001). Le Corbusier, London, Thames and Hudson.

- Jencks, Charles (2000) Le Corbusier and the Continual Revolution in Architecture, The Monacelli Press, ISBN 978-1-58093-077-2

- Jornod, Naïma and Jornod, Jean-Pierre (2005) Le Corbusier (Charles Edouard Jeanneret), catalogue raisonné de l'oeuvre peint, Skira, ISBN 88-7624-203-1

- Von Moos, Stanislaus (2009) Le Corbusier: Elements of A Synthesis, Rotterdam, 010 Publishers.

- Weber, Nicholas Fox (2008) Le Corbusier: A Life, Alfred A. Knopf, ISBN 0-375-41043-0

External links

| Library resources about Le Corbusier |

| By Le Corbusier |

|---|

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Le Corbusier |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Le Corbusier. |

- Fondation Le Corbusier – Official site

- Le Corbusier on Artsy.net

- Rajagopal, Avinash. 'The Little Prince' and Le Corbusier in Point of View, the Metropolis blog, Metropolis, January 29, 2014. Retrieved online at MetropolisMag.com January 29, 2014.

- Corbusier's Working Lifestyle: 'Working with Corbusier'

- Le Corbusier in Artfacts.Net

- Plummer, Henry. Cosmos of Light: The Sacred Architecture of Le Corbusier. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013.

- "Le Corbusier and the Sun". solarhousehistory.com.

|