Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

| |

| Motto |

"Bringing science solutions to the world" |

|---|---|

| Established |

August 26, 1931 (85 years ago) |

| Research type | Unclassified |

| Budget | $722 million (2013)[1] |

| Director | Paul Alivisatos |

| Staff | 4,000 |

| Students | 800 |

| Location | Berkeley, California, U.S. |

| Campus | 200 acres (0.81 km2) |

Operating agency | University of California[2] |

| 13[3] | |

| Website |

lbl |

The Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL or LBL), commonly referred to as Berkeley Lab, is a United States national laboratory located in the Berkeley Hills near Berkeley, California that conducts scientific research on behalf of the United States Department of Energy (DOE). It is managed and operated by the University of California,[2] The laboratory overlooks University of California, Berkeley's main campus.

History

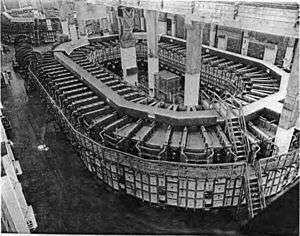

The laboratory was founded in 1931 as the Radiation Laboratory of the University of California, associated with the Physics Department, on August 26 by Ernest Lawrence. It centered physics research around his new instrument, the cyclotron, a type of particle accelerator for which he won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1939.[4] Throughout the 1930s, Lawrence pushed to create larger and larger machines for physics research, courting private philanthropists for funding. After the laboratory was scooped on a number of fundamental discoveries that they felt they ought to have made, the "cyclotroneers" began to collaborate more closely with the department's theoretical physicists, led by Robert Oppenheimer. The lab moved to its site on the hill above campus in 1940 as its machines, specifically the 184-inch (4.67 m) cyclotron, became too large for the university grounds.[4]

Lawrence courted government as his sponsor in the early years of the Manhattan Project, the American effort to produce the first atomic bomb during World War II, and along with Applied Physics Laboratory at Johns Hopkins (which helped develop the proximity fuse), and the MIT Radiation Laboratory (which helped to develop radar) ushered in the era of "Big Science". Lawrence's lab helped contribute to what has been judged to be the three most valuable technology developments of the war (the atomic bomb, proximity fuse, and radar). Using the newly created 184-inch cyclotron as a mass spectrometer, Lawrence and his colleagues developed the principle behind the electromagnetic enrichment of uranium, which was put to use in the calutrons (named after the university) at the massive Y-12 facility in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. The cyclotron was finished in November 1946; the Manhattan Project shut down two months later.

After the war, Lawrence sought to maintain strong government and military ties at his lab, which became incorporated into the new system of Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) (now Department of Energy (DOE)) National Laboratories, but in the early 1950s set out that the lab's purpose would be primarily non-classified research. For security purposes, classified weapons research was assigned to the more isolated locations, Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) (established during the war) in New Mexico and the new UC Radiation Laboratory at Livermore (today's Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL)). Livermore, about an hour southeast of Berkeley, was established at a former naval air station in 1952 by Lawrence and Edward Teller from what was originally a splinter from the original Radiation Laboratory. Some weapons-related and collaborative research continued at Berkeley Lab until the 1970s, however.

Shortly after the death of Lawrence in August 1958, the UC Radiation Laboratory (both branches) was renamed the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory and the Berkeley location became the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory in 1971,[5] although many continued to call it the "Rad Lab." Gradually, another shortened form came into common usage, "LBL". Its formal name was amended to Ernest Orlando Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in 1995, when "National" was added to the names of all DOE labs. "Ernest Orlando" was later dropped to shorten the name. Today, the lab is commonly referred to as "Berkeley Lab".[6]

Lab Directors

(2016- ): Michael Witherell

(2009–2016): Paul Alivisatos

(2004–2008): Steven Chu

(1989–2004): Charles Shank

(1980–1989): David Shirley

(1973–1980): Andrew Sessler

(1958–1972): Edwin McMillan

(1931–1958): Ernest Lawrence

Alvarez Physics Memos

The Alvarez Physics Memos are a set of informal working papers of the large group of physicists, engineers, computer programmers, and technicians led by Luis W. Alvarez from the early 1950s until his death in 1988. Over 1700 memos are available on-line, hosted by the Laboratory.[7]

Science mission

From the 1950s through the present, Berkeley Lab has maintained its status as a major international center for physics research, and has also diversified its research program into almost every realm of scientific investigation. The Laboratory's 14 scientific divisions are organized within the areas of Computing Sciences, General Sciences, Energy and Environmental Sciences, Life Sciences, and Photon Sciences. Many research projects are staffed and supported by multiple divisions, with computational and engineering integrated across the biosciences, general sciences, and energy sciences. The scientific divisions include: earth sciences, genomics, life sciences, chemical sciences, environmental energy technologies, materials science, physical biosciences, computational research, accelerator and fusion research, engineering, nuclear science, nuclear medicine and physics.

Berkeley Lab has six main science thrusts: soft x-ray science for discovery, climate change and environmental sciences, matter and force in the universe, energy efficiency and sustainable energy, computational science and networking, and biological science for energy research. It was Lawrence’s belief that scientific research is best done through teams of individuals with different fields of expertise, working together. His teamwork concept is a Berkeley Lab tradition that continues today.

Additionally Berkeley Lab is host to six major National User Facilities: the Advanced Light Source, the National Center for Electron Microscopy, National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, the Energy Sciences Network, the Molecular Foundry, and the Joint Genome Institute (JGI).

The Joint Genome Institute, in Walnut Creek, was founded in 1997 to unite the expertise and resources in genome mapping, DNA sequencing, technology development, and information sciences pioneered at the three genome centers at Berkeley Lab, Livermore, and Los Alamos. Today the JGI's partner laboratories include Berkeley Lab, LLNL, LANL, as well as Oak Ridge (ORNL), Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL), and the HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology (formerly associated with the Stanford Human Genome Center). The JGI workforce draws most heavily from Berkeley Lab and LLNL.

The laboratory also manages the Department of Energy's high speed research network, ESnet.[8]

Berkeley Lab is the lead partner in the Joint BioEnergy Institute (JBEI), located in Emeryville, California. Other partners are the Sandia National Laboratories, the University of California (UC) campuses of Berkeley and Davis, the Carnegie Institution for Science, and the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL). JBEI’s primary scientific mission is to advance the development of the next generation of biofuels – liquid fuels derived from the solar energy stored in plant biomass. JBEI is one of three new U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Bioenergy Research Centers (BRCs).

Operations and governance

The site consists of 76 buildings (owned by the U.S. Department of Energy) located on 200 acres (0.81 km2) owned by the university in the Berkeley Hills. Altogether, it has some 4,000 UC employees, of whom about 800 are students. Each year, the Lab also hosts more than 3,000 participating guests. There are approximately two dozen DOE employees stationed at the laboratory to provide federal oversight of Berkeley Lab's work for the DOE.

The laboratory director is appointed by the university regents and reports to the university president. In 2009, Paul Alivisatos was appointed interim director on January 21 to replace Steven Chu, who was sworn in as Secretary of Energy in the new Obama administration.[9] Ten months later, Alivisatos was officially named Berkeley Lab's seventh director by the regents on November 19. Although Berkeley Lab is governed by UC independently of the Berkeley campus, the two entities are closely interconnected: more than 200 Berkeley Lab researchers hold joint appointments as UC Berkeley faculty and more than 500 UC Berkeley graduate students conduct research at Berkeley Lab.

The Lab's budget for fiscal year 2011 was $735 million, plus $101 million from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

Scientific achievements, inventions, and discoveries

Notable scientific accomplishments at the Lab since World War II include the observation of the antiproton, the discovery of several transuranic elements, and the discovery of the accelerating universe.

Since its inception, 12 researchers associated with Berkeley Lab (Ernest Lawrence, Glenn T. Seaborg, Edwin M. McMillan, Owen Chamberlain, Emilio G. Segrè, Donald A. Glaser, Melvin Calvin, Luis W. Alvarez, Yuan T. Lee, Steven Chu, George F. Smoot and Saul Perlmutter) have been awarded the Nobel Prize.[10]

Seventy Berkeley Lab scientists are members of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences (NAS), one of the highest honors for a scientist in the United States.[10] Thirteen Berkeley Lab scientists have won the National Medal of Science, the nation's highest award for lifetime achievement in fields of scientific research.[10] Eighteen Berkeley Lab engineers have been elected to the National Academy of Engineering, and three Berkeley Lab scientists have been elected into the Institute of Medicine.[10]

Elements discovered by Berkeley Lab physicists include astatine, neptunium, plutonium, curium, americium, berkelium*, californium*, einsteinium, fermium, mendelevium, nobelium, lawrencium*, dubnium, and seaborgium*. Those elements listed with asterisks (*) are named after the University, Professors Lawrence and Seaborg. Seaborg was the principal scientist involved in their discovery. The element technetium was discovered after Ernest Lawrence gave Emilio Segrè a molybdenum strip from the Berkeley Lab cyclotron.[11]

Some inventions and discoveries to come out of Berkeley Lab include: "smart" windows with embedded electrodes that enable window glass to respond to changes in sunlight, synthetic genes for antimalaria and anti-AIDS superdrugs based on breakthroughs in synthetic biology, electronic ballasts for more efficient lighting, Home Energy Saver, the web's first do-it-yourself home energy audit tool, a pocket-sized DNA sampler called the PhyloChip, and the Berkeley Darfur Stove, which uses one-quarter as much firewood as traditional cook stoves. One of Berkeley Lab's most notable breakthroughs is the discovery of dark energy. During the 1980s and 1990s Berkeley Lab physicists and astronomers formed the Supernova Cosmology Project (SCP), using Type Ia supernovae as “standard candles” to measure the expansion rate of the universe. Their successful methods inspired competition, with the result that early in 1998 both the SCP and the High-Z Supernova Search Team announced the surprising discovery that expansion is accelerating; the cause was soon named dark energy.

Networking tools libpcap,[12] tcpdump, and traceroute were developed by the Network Engineering Group staff at the Laboratory.

As of July 2012, LBNL holds the world record for the most powerful laser.

Scandal

The fabricated evidence used to claim the creation of ununoctium and ununhexium (now livermorium) by Victor Ninov, a researcher employed at Berkeley Lab, led to the retraction of two articles.[13]

See also

- Center for the Advancement of Science in Space—operates the US National Laboratory on the ISS.

- List of Advanced Scientific Computing Research Leadership Computing Challenge allocations

- Lawrence Hall of Science

- Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

- Los Alamos National Laboratory

References

- ↑ About Berkeley Lab

- 1 2 University of California | Office of the President (accessed 2013-07-15).

- ↑ Nobel Prizes affiliated with Berkeley Lab

- 1 2 "Lawrence and His Laboratory: Chapter 1: A New Lab for a New Science". Lbl.gov. Retrieved 2009-07-12.

- ↑ "Ernest Lawrence and M. Stanley Livingston". American Physical Society. Retrieved May 9, 2014.

- ↑ "Ernest Lawrence's Cyclotron". Lbl.gov. 1958-08-27. Retrieved 2009-07-12.

- ↑ "Alvarez Physics Memos".

- ↑ "Department of Energy’s ESnet Wins 2009 Excellence.Gov Award for Effectively Leveraging Technology « Berkeley Lab News Center". Newscenter.lbl.gov. 2009-04-16. Retrieved 2009-07-12.

- ↑ "University of California - UC Newsroom | UC appoints Paul Alivisatos interim director of Berkeley Lab". Universityofcalifornia.edu. 2009-01-22. Retrieved 2009-07-12.

- 1 2 3 4 "About the Lab". www.lbl.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- ↑ "Chemical Elements Discovered at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory". Lbl.gov. 1999-06-07. Retrieved 2009-07-12.

- ↑ Jacobson, Van. "Libpcap". Securityfocus.com. Retrieved 2009-07-12.

- ↑ Dalton, Rex (2002). "The stars who fell to Earth" (PDF). Nature 420: 728–9. doi:10.1038/420728a. PMID 12490902. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. |

- Official website

- University of California Office of Laboratory Management

- The Rad Lab - Ernest Lawrence and the Cyclotron: American Institute of Physics web exhibit

- Lawrence and His Laboratory: A Historian's View of the Lawrence Years by J. L. Heilbron, Robert W. Seidel, and Bruce R. Wheaton.

- A Century of Physics at Berkeley: Seedtime for "Big Science", 1930-1950

- SPIE Video: Paul Alivisatos: Berkeley Lab director navigates uncertain times with a focus on research

Coordinates: 37°52′34″N 122°14′49″W / 37.876°N 122.247°W

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

|