Law of mass action

In chemistry, the law of mass action is a mathematical model that explains and predicts behaviours of solutions in dynamic equilibrium. Simply put, it states that the rate of a chemical reaction is proportional to the product of the masses of the reactants. Necessarily, this implies that for a chemical reaction mixture that is in equilibrium, the ratio between the concentration of reactants and products is constant.[1]

Two aspects are involved in the initial formulation of the law: 1) the equilibrium aspect, concerning the composition of a reaction mixture at equilibrium and 2) the kinetic aspect concerning the rate equations for elementary reactions. Both aspects stem from the research performed by Cato M. Guldberg and Peter Waage between 1864 and 1879 in which equilibrium constants were derived by using kinetic data and the rate equation which they had proposed. Guldberg and Waage also recognized that chemical equilibrium is a dynamic process in which rates of reaction for the forward and backward reactions must be equal at chemical equilibrium. In order to derive the expression of the equilibrium constant appealing to kinetics, the expression of the rate equation must be used. The expression of the rate equations has been rediscovered later independently by Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff.

The law is a statement about equilibrium and gives an expression for the equilibrium constant, a quantity characterizing chemical equilibrium. In modern chemistry this is derived using equilibrium thermodynamics.

History

Two chemist CM Guldberg and P Waage in 1864 proposed the law of mass action to define the equilibrium state. Two chemist generally express the composition of mixture in terms of numerical values this vaLues relates the amount of product to describes the equilibrium state. Cato Maximilian Guldberg and Peter Waage, building on Claude Louis Berthollet’s ideas[2] about reversible chemical reactions, proposed the Law of Mass Action in 1864.[3][4][5] These papers, in Norwegian, went largely unnoticed, as did the later publication (in French) of 1867 which contained a modified law and the experimental data on which that law was based.[6]

In 1877 van 't Hoff independently came to similar conclusions,[7] but was unaware of the earlier work, which prompted Guldberg and Waage to give a fuller and further developed account of their work, in German, in 1879.[8] Van 't Hoff then accepted their priority.

1864

The equilibrium state (composition)

In their first paper,[3] Guldberg and Waage suggested that in a reaction such as

- A + B

A' + B'

A' + B'

the "chemical affinity" or "reaction force" between A and B did not just depend on the chemical nature of the reactants, as had previously been supposed, but also depended on the amount of each reactant in a reaction mixture. Thus the Law of Mass Action was first stated as follows:

- When two reactants, A and B, react together at a given temperature in a "substitution reaction," the affinity, or chemical force between them, is proportional to the active masses, [A] and [B], each raised to a particular power

![\mbox{affinity} = \alpha[A]^a[B]^b\!](../I/m/1c6757c8fa0325d5483078d850520e61.png) .

.

In this context a substitution reaction was one such as alcohol + acid  ester + water. Active mass was defined in the 1879 paper as "the amount of substance in the sphere of action".[9] For species in solution active mass is equal to concentration. For solids active mass is taken as a constant.

ester + water. Active mass was defined in the 1879 paper as "the amount of substance in the sphere of action".[9] For species in solution active mass is equal to concentration. For solids active mass is taken as a constant.  , a and b were regarded as empirical constants, to be determined by experiment.

, a and b were regarded as empirical constants, to be determined by experiment.

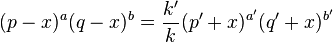

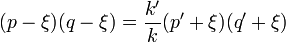

At equilibrium the chemical force driving the forward reaction must be equal to the chemical force driving the reverse reaction. Writing the initial active masses of A,B, A' and B' as p, q, p' and q' and the dissociated active mass at equilibrium as  , this equality is represented by

, this equality is represented by

represents the amount of reagents A and B that has been converted into A' and B'. Calculations based on this equation are reported in the second paper.[4]

represents the amount of reagents A and B that has been converted into A' and B'. Calculations based on this equation are reported in the second paper.[4]

Dynamic approach to the equilibrium state

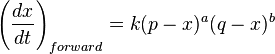

The third paper of 1864[5] was concerned with the kinetics of the same equilibrium system. Writing the dissociated active mass at some point in time as x, the rate of reaction was given as

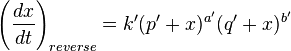

Likewise the reverse reaction of A' with B' proceeded at a rate given by

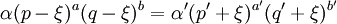

The overall rate of conversion is the difference between these rates, so at equilibrium (when the composition stops changing) the two rates of reaction must be equal. Hence

...

...

1867

The rate expressions given in the 1864 paper could not be integrated, so they were simplified as follows.[6] The chemical force was assumed to be directly proportional to the product of the active masses of the reactants.

This is equivalent to setting the exponents a and b of the earlier theory to one. The proportionality constant was called an affinity constant, k. The equilibrium condition for an "ideal" reaction was thus given the simplified form

[A]eq, [B]eq etc. are the active masses at equilibrium. In terms of the initial amounts reagents p,q etc. this becomes

The ratio of the affinity coefficients, k'/k, can be recognized as an equilibrium constant. Turning to the kinetic aspect, it was suggested that the velocity of reaction, v, is proportional to the sum of chemical affinities (forces). In its simplest form this results in the expression

where  is the proportionality constant. Actually, Guldberg and Waage used a more complicated expression which allowed for interaction between A and A', etc. By making certain simplifying approximations to those more complicated expressions, the rate equation could be integrated and hence the equilibrium quantity

is the proportionality constant. Actually, Guldberg and Waage used a more complicated expression which allowed for interaction between A and A', etc. By making certain simplifying approximations to those more complicated expressions, the rate equation could be integrated and hence the equilibrium quantity  could be calculated. The extensive calculations in the 1867 paper gave support to the simplified concept, namely,

could be calculated. The extensive calculations in the 1867 paper gave support to the simplified concept, namely,

- The rate of a reaction is proportional to the product of the active masses of the reagents involved.

This is an alternative statement of the Law of Mass Action.

1879

In the 1879 paper[8] the assumption that reaction rate was proportional to the product of concentrations was justified microscopically in terms of collision theory, as had been developed for gas reactions. It was also proposed that the original theory of the equilibrium condition could be generalised to apply to any arbitrary chemical equilibrium.

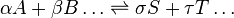

The exponents α, β etc. are explicitly identified for the first time as the stoichiometric coefficients for the reaction. Since reaction rate was considered to be proportional to chemical affinity, it follows that for a general reaction of the type

where [A], [B], [S] and [T] are active masses and k+ and k− are affinity constants. Since at equilibrium the affinities and reaction rates for forward and backward reactions are equal, it follows that

Example;

Consider the hypothetical equation in which a moles of A react with b moles of B to give d moles of D

aA +bB → cC +dD

RATE OF FORWARD REACTION ∝[A]a[B]b

RATE OF FORWARD REACTION =Kf[A]a[B]b

RATE OF REVERSE REACTION ∝ [C]c[D]d

RATE OF REVERSE REACTION =Kr[C]c[D]d

kf/kr=[C]c[D]d/[A]a[B]b

Kc=[C]c[D]d/[A]a[B]b

Kc is called equilibrium constant and this equation is called equilibrium constant expression

Contemporary statement of the law

The affinity constants, k+ and k-, of the 1879 paper can now be recognised as rate constants. The equilibrium constant, K, was derived by setting the rates of forward and backward reactions to be equal. This also meant that the chemical affinities for the forward and backward reactions are equal. The resultant expression

is correct[1] even from the modern perspective, apart from the use of concentrations instead of activities (the concept of chemical activity was developed by Josiah Willard Gibbs, in the 1870s, but was not widely known in Europe until the 1890s). The derivation from the reaction rate expressions is no longer considered to be valid. Nevertheless, Guldberg and Waage were on the right track when they suggested that the driving force for both forward and backward reactions is equal when the mixture is at equilibrium. The term they used for this force was chemical affinity. Today the expression for the equilibrium constant is derived by setting the chemical potential of forward and backward reactions to be equal. The generalisation of the Law of Mass Action, in terms of affinity, to equilibria of arbitrary stoichiometry was a bold and correct conjecture.

The hypothesis that reaction rate is proportional to reactant concentrations is, strictly speaking, only true for elementary reactions (reactions with a single mechanistic step), but the empirical rate expression

is also applicable to second order reactions that may not be concerted reactions. Guldberg and Waage were fortunate in that reactions such as ester formation and hydrolysis, on which they originally based their theory, do indeed follow this rate expression.

In general many reactions occur with the formation of reactive intermediates, and/or through parallel reaction pathways. However, all reactions can be represented as a series of elementary reactions and, if the mechanism is known in detail, the rate equation for each individual step is given by the  expression so that the overall rate equation can be derived from the individual steps. When this is done the equilibrium constant is obtained correctly from the rate equations for forward and backward reaction rates.

expression so that the overall rate equation can be derived from the individual steps. When this is done the equilibrium constant is obtained correctly from the rate equations for forward and backward reaction rates.

In biochemistry, there has been significant interest in the appropriate mathematical model for chemical reactions occurring in the intracellular medium. This is in contrast to the initial work done on chemical kinetics, which was in simplified systems where reactants were in a relatively dilute, pH-buffered, aqueous solution. In more complex environments, where bound particles may be prevented from disassociation by their surroundings, or diffusion is slow or anomalous, the model of mass action does not always describe the behavior of the reaction kinetics accurately. Several attempts have been made to modify the mass action model, but consensus has yet to be reached. Popular modifications replace the rate constants with functions of time and concentration. As an alternative to these mathematical constructs, one school of thought is that the mass action model can be valid in intracellular environments under certain conditions, but with different rates than would be found in a dilute, simple environment .

The fact that Guldberg and Waage developed their concepts in steps from 1864 to 1867 and 1879 has resulted in much confusion in the literature as to which equation the Law of Mass Action refers. It has been a source of some textbook errors.[10] Thus, today the "law of mass action" sometimes refers to the (correct) equilibrium constant formula,

[11]

[12]

[13]

[14]

[15]

[16]

[17]

[18]

[19]

[20]

and at other times to the (usually incorrect)  rate formula.

[21]

[22]

rate formula.

[21]

[22]

Applications to other fields

In semiconductor physics

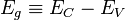

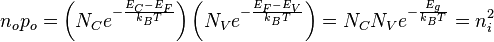

The law of mass action also has implications in semiconductor physics. Regardless of doping, the product of electron and hole densities is a constant at equilibrium. This constant depends on the thermal energy of the system (i.e. the product of the Boltzmann constant,  , and temperature,

, and temperature,  ), as well as the band gap (the energy separation between conduction and valence bands,

), as well as the band gap (the energy separation between conduction and valence bands,  ) and effective density of states in the valence

) and effective density of states in the valence  and conduction

and conduction  bands. When the equilibrium electron

bands. When the equilibrium electron  and hole

and hole  densities are equal, their density is called the intrinsic carrier density

densities are equal, their density is called the intrinsic carrier density  as this would be the value of

as this would be the value of  and

and  in a perfect crystal. Note that the final product is independent of the Fermi level

in a perfect crystal. Note that the final product is independent of the Fermi level  :

:

Diffusion in condensed matter

Yakov Frenkel represented diffusion process in condensed matter as an ensemble of elementary jumps and quasichemical interactions of particles and defects. Henry Eyring applied his theory of absolute reaction rates to this quasichemical representation of diffusion. Mass action law for diffusion leads to various nonlinear versions of Fick's law.[23]

In mathematical ecology

The Lotka–Volterra equations describe dynamics of the predator-prey systems. The rate of predation upon the prey is assumed to be proportional to the rate at which the predators and the prey meet; this rate is evaluated as xy, where x is the number of prey, y is the number of predator. This is a typical example of the law of mass action.

In mathematical epidemiology

The law of mass action forms the basis of the compartmental model of disease spread in mathematical epidemiology, in which a population of humans, animals or other individuals is divided into categories of susceptible, infected, and recovered (immune). The SIR model is a useful abstraction of disease dynamics which applies well to many disease systems and provides useful outcomes in many circumstances when the Mass Action Principle applies. Individuals in human or animal populations - unlike molecules in an ideal solution - do not mix homogeneously. There are some disease examples in which this non-homogeneity is great enough such that the outputs of the SIR model are invalid. For these situations in which the assumptions of mass action do not apply, more sophisticated graph theory models may be useful. For more information, see Compartmental models in epidemiology.

In sociophysics

Sociophysics[24] uses tools and concepts from physics and physical chemistry to describe some aspects of social and political behavior. It attempts to explain why and how humans behave much like atoms, at least in some aspects of their collective lives. The law of mass action (generalized if it is necessary) is the main tool to produce the equation of interactions of humans in sociophysics.

See also

References

- 1 2 Chieh, Chung. "Chemical Equilibria - The Law of Mass Action". Chemical reactions, chemical equilibria, and electrochemistry. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

The law of mass action is universal, applicable under any circumstance... The mass action law states that if the system is at equilibrium at a given temperature, then the following ratio is a constant.

- ↑ Levere, Trevor, H. (1971). Affinity and Matter – Elements of Chemical Philosophy 1800–1865. Gordon and Breach Science Publishers. ISBN 2-88124-583-8.

- 1 2 C.M. Guldberg and P. Waage,"Studies Concerning Affinity" C. M. Forhandlinger: Videnskabs-Selskabet i Christiana (1864), 35

- 1 2 P. Waage, "Experiments for Determining the Affinity Law" ,Forhandlinger i Videnskabs-Selskabet i Christiania, (1864) 92.

- 1 2 C.M. Guldberg, "Concerning the Laws of Chemical Affinity", C. M. Forhandlinger i Videnskabs-Selskabet i Christiania (1864) 111

- 1 2 C.M. Guldberg and P. Waage, "Experiments concerning Chemical Affinity"; German translation by Abegg in Ostwald's Klassiker der Exacten Wissenschaften, no. 104, Wilhelm Engleman, Leipzig, 1899, pp 10-125

- ↑ J.H. van 't Hoff, Berichte der Berliner Chem. Ges., (1877) 10

- 1 2 C.M. Guldberg and P. Waage, "Concerning Chemical Affinity" Erdmann's Journal für Practische Chemie, (1879), 127, 69-114. Reprinted, with comments by Abegg in Ostwald's Klassiker der Exacten Wissenschaften, no. 104, Wilhelm Engleman, Leipzig, 1899, pp 126-171

- ↑ It was stated in the 1879 paper that "the sphere of action can be represented by unit volume"

- ↑ "Textbook errors IX: More About the Laws of Reaction Rates and of Equilibrium", E.A. Guggenheim, J. Chem. Ed., (1956) 33, 544-545

- ↑ Law of Mass Action

- ↑ SC.edu

- ↑ The Law of Mass Action

- ↑ SFSU.edu

- ↑ Recap of FundamentRecap of Fundamental Acid-Base Concepts

- ↑ Chemical Equilibria: Basic Concepts

- ↑ Chemical equilibrium - The Law of Mass Action

- ↑ Indiana.edu

- ↑ Berkeley.edu

- ↑ General Chemistry Online: FAQ: Acids and bases: What is the pH at the equivalence point an HF/NaOH titration?

- ↑ law of mass action definition

- ↑ Lab 4 - Slow Manifolds

- ↑ A.N. Gorban, H.P. Sargsyan and H.A. Wahab (2011), Quasichemical Models of Multicomponent Nonlinear Diffusion, Mathematical Modelling of Natural Phenomena, Volume 6 / Issue 05, 184−262.

- ↑ S. Galam, Sociophysics. A Physicist's Modeling of Psycho-political Phenomena, Springer, 2012, DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4614-2032-3, ISBN 978-1-4614-2032-3

Further reading

- Studies Concerning Affinity. P. Waage and C.M. Guldberg; Henry I. Abrash, Translator.

- "Guldberg and Waage and the Law of Mass Action", E.W. Lund, J. Chem. Ed., (1965), 42, 548-550.

- A simple explanation of the mass action law. H. Motulsky.

![\mbox{affinity} = \alpha[A][B]\!](../I/m/6b2b5134eb77c8fde09cc1fb301e80c8.png)

![k[A]_\text{eq}[B]_\text{eq}=k'[A']_\text{eq}[B']_\text{eq}\!](../I/m/3c403026e4568a9f29af7063135fd055.png)

![\mbox{affinity}=k[A]^{\alpha}[B]^{\beta}\dots\!](../I/m/f010d7d2d7523fa1548c7ac4b63269ae.png)

![\mbox{forward reaction rate} = k_+ [A]^\alpha[B]^\beta \dots \,\!](../I/m/64570cc01cf620fc169d59539520bdd0.png)

![\mbox{backward reaction rate} = k_{-} [S]^\sigma[T]^\tau \dots \,\!](../I/m/3fae4224ee5132768209962e9b25d43c.png)

![K=\frac{k_+}{k_-}=\frac{[S]^\sigma [T]^\tau \dots } {[A]^\alpha [B]^\beta \dots}](../I/m/51b5ea0702ef2d7ee40e8107bfd537e2.png)

![K=\frac{[S]^\sigma [T]^\tau \dots } {[A]^\alpha [B]^\beta \dots}\,](../I/m/414f92cdd1efd5eb363625d22311736a.png)

![r_f=k_f[A][B]\,](../I/m/2a612e72c938bcd63c363c2bb459db03.png)