Lattice energy

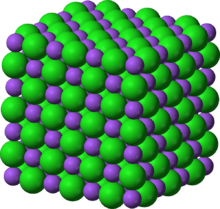

The lattice energy of a crystalline solid is usually defined as the energy of formation of the crystal from infinitely-separated ions and as such is invariably negative. The concept of lattice energy was originally developed for rocksalt-structured and sphalerite-structured compounds like NaCl and ZnS, where the ions occupy high-symmetry crystal lattice sites. In the case of NaCl, the lattice energy is the energy released by the reaction

- Na+ (g) + Cl− (g) → NaCl (s)

which would amount to -786 kJ/mol.[1]

Some older textbooks define lattice energy with the opposite sign,[2] i.e. the energy required to convert the crystal into infinitely separated gaseous ions in vacuum, an endothermic process. Following this convention, the lattice energy of NaCl would be +786 kJ/mol. The lattice energy for ionic crystals such as sodium chloride, metals such as iron, or covalently linked materials such as diamond is considerably greater in magnitude than for solids such as sugar or iodine, whose neutral molecules interact only by weaker dipole-dipole or van der Waals forces.

The precise value of the lattice energy may not be determined experimentally, because of the impossibility of preparing an adequate amount of gaseous ions or atoms and measuring the energy released during their condensation to form the solid. However, the value of the lattice energy may either be derived theoretically from electrostatics or from a thermodynamic cycling reaction, the Born–Haber cycle.

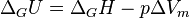

The relationship between the molar lattice energy and the molar lattice enthalpy is given by the following equation:

, where

, where  is the molar lattice energy,

is the molar lattice energy,  the molar lattice enthalpy and

the molar lattice enthalpy and  the change of the volume per mol. Therefore the lattice enthalpy further takes into account that work has to be performed against an outer pressure

the change of the volume per mol. Therefore the lattice enthalpy further takes into account that work has to be performed against an outer pressure  .

.

Theoretical treatments

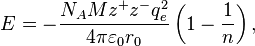

Born–Landé equation

In 1918[3] Born and Landé proposed that the lattice energy could be derived from the electric potential of the ionic lattice and a repulsive potential energy term.[1]

where

- NA is the Avogadro constant;

- M is the Madelung constant, relating to the geometry of the crystal;

- z+ is the charge number of cation;

- z− is the charge number of anion;

- qe is the elementary charge, equal to 1.6022×10−19 C;

- ε0 is the permittivity of free space, equal to 8.854×10−12 C2 J−1 m−1;

- r0 is the distance to closest ion; and

- n is the Born exponent, a number between 5 and 12, determined experimentally by measuring the compressibility of the solid, or derived theoretically.[4]

The Born–Landé equation gives a reasonable fit to the lattice energy.[1]

| Compound | Calculated Lattice Energy | Experimental Lattice Energy |

|---|---|---|

| NaCl | −756 kJ/mol | −787 kJ/mol |

| LiF | −1007 kJ/mol | −1046 kJ/mol |

| CaCl2 | −2170 kJ/mol | −2255 kJ/mol |

From the Born–Landé equation it can be seen that the lattice energy of a compound is dependent on a number of factors

- as the charges on the ions increase the lattice energy increases (becomes more negative),

- when ions are closer together the lattice energy increases (becomes more negative)

Barium oxide (BaO), for instance, which has the NaCl structure and therefore the same Madelung constant, has a bond radius of 275 picometers and a lattice energy of -3054 kJ/mol, while sodium chloride (NaCl) has a bond radius of 283 picometers and a lattice energy of -786 kJ/mol.

Kapustinskii equation

The Kapustinskii equation can be used as a simpler way of deriving lattice energies where high precision is not required.[1]

Effect of polarisation

For ionic compounds with ions occupying lattice sites with crystallographic point groups C1, C1h, Cn or Cnv (n = 2, 3, 4 or 6) the concept of the lattice energy and the Born–Haber cycle has to be extended.[5] In these cases the polarization energy Epol associated with ions on polar lattice sites has to be included in the Born–Haber cycle and the solid formation reaction has to start from the already polarized species. As an example, one may consider the case of iron-pyrite FeS2, where sulfur ions occupy lattice site of point symmetry group C3. The lattice energy defining reaction then reads

- Fe2+ (g) + 2 pol S− (g) → FeS2 (s)

where pol S− stands for the polarized, gaseous sulfur ion. It has been shown that the neglection of the effect led to 15% difference between theoretical and experimental thermodynamic cycle energy of FeS2 that reduced to only 2%, when the sulfur polarization effects were included.[6]

Notes for the Term

1. It is the gaseous ions that combine

2. The lattice energy is always exothermic: the value of ΔH is always negative, because the definition specifies the bonding together of ions, not the separation of ions.[7]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 David Arthur Johnson, Metals and Chemical Change,Open University, Royal Society of Chemistry, 2002,ISBN 0-85404-665-8

- ↑ Zumdahl, Steven S. (1997). Chemistry (4th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 357–358. ISBN 0-669-41794-7.

- ↑ I.D. Brown, The chemical Bond in Inorganic Chemistry, IUCr monographs in crystallography, Oxford University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-19-850870-0

- ↑ Cotton, F. Albert; Wilkinson, Geoffrey; (1966). Advanced Inorganic Chemistry (2d Edn.) New York:Wiley-Interscience.

- ↑ M. Birkholz (1995). "Crystal-field induced dipoles in heteropolar crystals – I. concept" (PDF). Z. Phys. B 96: 325–332. Bibcode:1995ZPhyB..96..325B. doi:10.1007/BF01313054.

- ↑ M. Birkholz (1992). "The crystal energy of pyrite" (PDF). J. Phys.: Condens. Matt. 4: 6227. Bibcode:1992JPCM....4.6227B. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/4/29/007.

- ↑ Roger Norris, Lawrie Ryan, David Acaster (2011). Cambridge International AS and A Level Chemistry Coursebook (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-521-12661-8.

| ||||||||||||||||||