Lattice Boltzmann methods

Lattice Boltzmann methods (LBM) (or thermal lattice Boltzmann methods (TLBM)) is a class of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) methods for fluid simulation. Instead of solving the Navier–Stokes equations, the discrete Boltzmann equation is solved to simulate the flow of a Newtonian fluid with collision models such as Bhatnagar–Gross–Krook (BGK). By simulating streaming and collision processes across a limited number of particles, the intrinsic particle interactions evince a microcosm of viscous flow behavior applicable across the greater mass.

Algorithm

LBM is a relatively new simulation technique for complex fluid systems and has attracted interest from researchers in computational physics. Unlike the traditional CFD methods, which solve the conservation equations of macroscopic properties (i.e., mass, momentum, and energy) numerically, LBM models the fluid consisting of fictive particles, and such particles perform consecutive propagation and collision processes over a discrete lattice mesh. Due to its particulate nature and local dynamics, LBM has several advantages over other conventional CFD methods, especially in dealing with complex boundaries, incorporating microscopic interactions, and parallelization of the algorithm. A different interpretation of the lattice Boltzmann equation is that of a discrete-velocity Boltzmann equation. The numerical methods of solution of the system of partial differential equations then gives rise to a discrete map, which can be interpreted as the propagation and collision of fictitious particles.

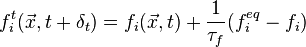

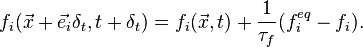

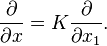

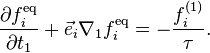

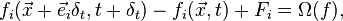

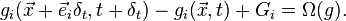

In the computer algorithm, the collision and streaming step are defined as follows:

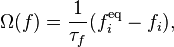

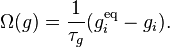

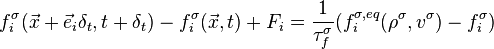

Collision step:

Streaming step:

Here i are the directions of momentum.

Advantages

- The LBM method was designed from scratch to run efficiently on massively parallel architectures, ranging from inexpensive embedded FPGAs and DSPs up to GPUs and heterogeneous clusters and supercomputers (even with a slow interconnection network). It enables complex physics and sophisticated algorithms. Efficiency leads to a qualitatively new level of understanding, since it allows solving problems that previously could not be approached (or only with insufficient accuracy).

- The method originates from a molecular description of a fluid and can directly incorporate physical terms stemming from a knowledge of the interaction between molecules. Hence it is an indispensable instrument in fundamental research, as it keeps the cycle between the elaboration of a theory and the formulation of a corresponding numerical model short.

- Automated data pre-processing and mesh generation in a time that accounts for a small fraction of the total simulation.

- Parallel data analysis, post-processing and evaluation.

- Fully resolved multi-phase flow with small droplets and bubbles.

- Fully resolved flow through complex geometries and porous media.

- Complex, coupled flow with heat transfer and chemical reactions.

Limitations

Despite the increasing popularity of LBM in simulating complex fluid systems, this novel approach has some limitations. At present, high-Mach number flows in aerodynamics are still difficult for LBM, and a consistent thermo-hydrodynamic scheme is absent. However, as with Navier–Stokes based CFD, LBM methods have been successfully coupled to thermal-specific solutions to enable heat transfer (solids-based conduction, convection and radiation) simulation capability. For multiphase/multicomponent models, the interface thickness is usually large and the density ratio across the interface is small when compared with real fluids. Recently this problem has been resolved by Yuan and Schaefer who improved on models by Shan and Chen, Swift, and He, Chen, and Zhang. They were able to reach density ratios of 1000:1 by simply changing the equation of state.

Nevertheless, the wide applications and fast advancements of this method during the past twenty years have proven its potential in computational physics, including microfluidics: LBM demonstrates promising results in the area of high Knudsen number flows.

Development from the LGA method

LBM originated from the lattice gas automata (LGA) method, which can be considered as a simplified fictitious molecular dynamics model in which space, time, and particle velocities are all discrete. For example, in the 2-dimensional FHP Model each lattice node is connected to its neighbors by 6 lattice velocities on a triangular lattice; there can be either 0 or 1 particles at a lattice node moving with a given lattice velocity. After a time interval, each particle will move to the neighboring node in its direction; this process is called the propagation or streaming step. When more than one particle arrives at the same node from different directions, they collide and change their velocities according to a set of collision rules. Streaming steps and collision steps alternate. Suitable collision rules should conserve the particle number (mass), momentum, and energy before and after the collision. LGA suffer from several innate defects for use in hydrodynamic simulations: lack of Galilean invariance for fast flows, statistical noise and poor Reynolds number scaling with lattice size. LGA are, however, well suited to simplify and extend the reach of reaction diffusion and molecular dynamics models.

The main motivation for the transition from LGA to LBM was the desire to remove the statistical noise by replacing the Boolean particle number in a lattice direction with its ensemble average, the so-called density distribution function. Accompanying this replacement, the discrete collision rule is also replaced by a continuous function known as the collision operator. In the LBM development, an important simplification is to approximate the collision operator with the Bhatnagar-Gross-Krook (BGK) relaxation term. This lattice BGK (LBGK) model makes simulations more efficient and allows flexibility of the transport coefficients. On the other hand, it has been shown that the LBM scheme can also be considered as a special discretized form of the continuous Boltzmann equation. From Chapman-Enskog theory, one can recover the governing continuity and Navier–Stokes equations from the LBM algorithm. In addition, th also directly available from the density distributions and hence there is no extra Poisson equation to be solved as in traditional CFD methods.

Lattices and the DnQm classification

Lattice Boltzmann models can be operated on a number of different lattices, both cubic and triangular, and with or without rest particles in the discrete distribution function.

A popular way of classifying the different methods by lattice is the DnQm scheme. Here "Dn" stands for "n dimensions", while "Qm" stands for "m speeds". For example, D3Q15 is a 3-dimensional lattice Boltzmann model on a cubic grid, with rest particles present. Each node has a crystal shape and can deliver particles to 15 nodes: each of the 6 neighboring nodes that share a surface, the 8 neighboring nodes sharing a corner, and itself.[1] (The D3Q15 model does not contain particles moving to the 12 neighboring nodes that share an edge; adding those would create a "D3Q27" model.)

Real quantities as space and time need to be converted to lattice units prior to simulation. Nondimensional quantities, like the Reynolds number, remain the same.

Lattice units conversion

In most lattice Boltzmann simulations  is the basic unit for lattice spacing, so if the domain of length

is the basic unit for lattice spacing, so if the domain of length  has

has  lattice units along its entire length, the space unit is simply defined as

lattice units along its entire length, the space unit is simply defined as  . Speeds in lattice Boltzmann simulations are typically given in terms of the speed of sound. The discrete time unit can therefore be given as

. Speeds in lattice Boltzmann simulations are typically given in terms of the speed of sound. The discrete time unit can therefore be given as  , where the denominator

, where the denominator  is the physical speed of sound.[2]

is the physical speed of sound.[2]

For small-scale flows (such as those seen in porous media mechanics), operating with the true speed of sound can lead to unacceptably short time steps. It is therefore common to raise the lattice Mach number to something much larger than the real Mach number, and compensating for this by raising the viscosity as well in order to preserve the Reynolds number.[3]

Simulation of mixtures

Simulating multiphase/multicomponent flows has always been a challenge to conventional CFD because of the moving and deformable interfaces. More fundamentally, the interfaces between different phases (liquid and vapor) or components (e.g., oil and water) originate from the specific interactions among fluid molecules. Therefore it is difficult to implement such microscopic interactions into the macroscopic Navier–Stokes equation. However, in LBM, the particulate kinetics provides a relatively easy and consistent way to incorporate the underlying microscopic interactions by modifying the collision operator. Several LBM multiphase/multicomponent models have been developed. Here phase separations are generated automatically from the particle dynamics and no special treatment is needed to manipulate the interfaces as in traditional CFD methods. Successful applications of multiphase/multicomponent LBM models can be found in various complex fluid systems, including interface instability, bubble/droplet dynamics, wetting on solid surfaces, interfacial slip, and droplet electrohydrodynamic deformations.

A lattice Boltzmann model for simulation of gas mixture combustion capable of accommodating significant density variations at low-Mach number regime has been recently proposed.[4]

To this respect, it is worth to notice that, since LBM deals with a larger set of fields (as compared to conventional CFD), the simulation of reactive gas mixtures presents some additional challenges in terms of memory demand as far as large detailed combustion mechanisms are concerned. Those issues may be addressed, though, by resorting to systematic model reduction techniques.[5][6][7]

Thermal lattice-Boltzmann method

Currently (2009), a thermal lattice-Boltzmann method (TLBM) falls into one of three categories: the multi-speed approach,[8] the passive scalar approach,[9] and the thermal energy distribution.[10]

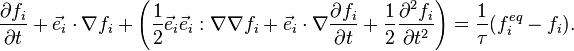

Derivation of Navier–Stokes equation from discrete LBE

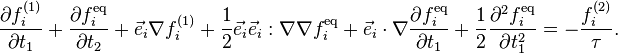

Starting with the discrete lattice Boltzmann equation (also referred to as LBGK equation due to the collision operator used). We first do a 2nd-order Taylor series expansion about the left side of the LBE. This is chosen over a simpler 1st-order Taylor expansion as the discrete LBE cannot be recovered. When doing the 2nd-order Taylor series expansion, the zero derivative term and the first term on the right will cancel, leaving only the first and second derivative terms of the Taylor expansion and the collision operator:

For simplicity, write  as

as  . The slightly simplified Taylor series expansion is then as follows, where ":" is the colon product between dyads:

. The slightly simplified Taylor series expansion is then as follows, where ":" is the colon product between dyads:

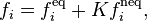

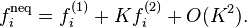

By expanding the particle distribution function into equilibrium and non-equilibrium components and using the Chapman-Enskog expansion, where  is the Knudsen number, the Taylor-expanded LBE can be decomposed into different magnitudes of order for the Knudsen number in order to obtain the proper continuum equations:

is the Knudsen number, the Taylor-expanded LBE can be decomposed into different magnitudes of order for the Knudsen number in order to obtain the proper continuum equations:

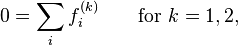

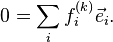

The equilibrium and non-equilibrium distributions satisfy the following relations to their macroscopic variables (these will be used later, once the particle distributions are in the "correct form" in order to scale from the particle to macroscopic level):

The Chapman-Enskog expansion is then:

By substituting the expanded equilibrium and non-equilibrium into the Taylor expansion and separating into different orders of  , the continuum equations are nearly derived.

, the continuum equations are nearly derived.

For order  :

:

For order  :

:

Then, the second equation can be simplified with some algebra and the first equation into the following:

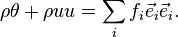

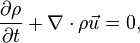

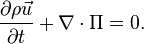

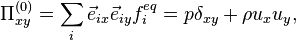

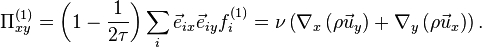

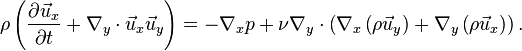

Applying the relations between the particle distribution functions and the macroscopic properties from above, the mass and momentum equations are achieved:

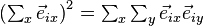

The momentum flux tensor  has the following form then:

has the following form then:

where  is shorthand for the square of the sum of all the components of

is shorthand for the square of the sum of all the components of  (i. e.

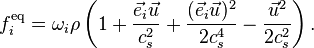

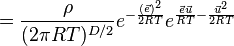

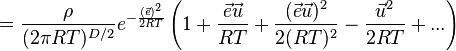

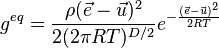

(i. e.  ), and the equilibrium particle distribution with second order to be comparable to the Navier–Stokes equation is:

), and the equilibrium particle distribution with second order to be comparable to the Navier–Stokes equation is:

The equilibrium distribution is only valid for small velocities or small Mach numbers. Inserting the equilibrium distribution back into the flux tensor leads to:

Finally, the Navier–Stokes equation is recovered under the assumption that density variation is small:

This derivation follows the work of Chen and Doolen.[11]

Mathematical equations for simulations

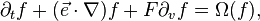

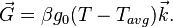

The continuous Boltzmann equation is an evolution equation for a single particle probability distribution function  and the internal energy density distribution function

and the internal energy density distribution function  (He et al.) are each respectively:

(He et al.) are each respectively:

where  is related to

is related to  by

by

is an external force,

is an external force,  is a collision integral, and

is a collision integral, and  (also labeled by

(also labeled by  in literature) is the microscopic velocity. The external force

in literature) is the microscopic velocity. The external force  is related to temperature external force

is related to temperature external force  by the relation below. A typical test for one's model is the Rayleigh–Bénard convection for

by the relation below. A typical test for one's model is the Rayleigh–Bénard convection for  .

.

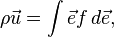

Macroscopic variables such as density  , velocity

, velocity  , and temperature

, and temperature  can be calculated as the moments of the density distribution function:

can be calculated as the moments of the density distribution function:

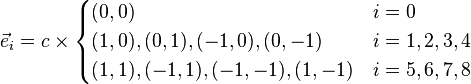

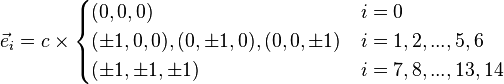

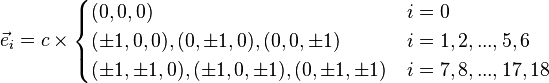

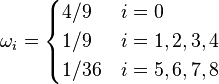

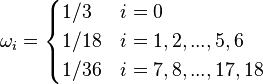

The lattice Boltzmann method discretizes this equation by limiting space to a lattice and the velocity space to a discrete set of microscopic velocities (i. e.  ). The microscopic velocities in D2Q9, D3Q15, and D3Q19 for example are given as:

). The microscopic velocities in D2Q9, D3Q15, and D3Q19 for example are given as:

The single-phase discretized Boltzmann equation for mass density and internal energy density are:

The collision operator is often approximated by a BGK collision operator under the condition it also satisfies the conservation laws:

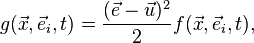

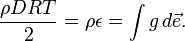

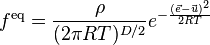

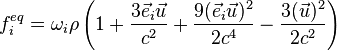

In the collision operator  is the discrete, equilibrium particle probability distribution function. In D2Q9 and D3Q19, it is shown below for an incompressible flow in continuous and discrete form where D, R, and T are the dimension, universal gas constant, and absolute temperature respectively. The partial derivation for the continuous to discrete form is provided through a simple derivation to second order accuracy.

is the discrete, equilibrium particle probability distribution function. In D2Q9 and D3Q19, it is shown below for an incompressible flow in continuous and discrete form where D, R, and T are the dimension, universal gas constant, and absolute temperature respectively. The partial derivation for the continuous to discrete form is provided through a simple derivation to second order accuracy.

Letting  yields the final result:

yields the final result:

As much work has already been done on a single-component flow, the following TLBM will be discussed. The multicomponent/multiphase TLBM is also more intriguing and useful than simply one component. To be in line with current research, define the set of all components of the system (i. e. walls of porous media, multiple fluids/gases, etc.)  with elements

with elements  .

.

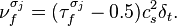

The relaxation parameter, , is related to the kinematic viscosity,

, is related to the kinematic viscosity, , by the following relationship:

, by the following relationship:

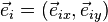

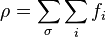

The moments of the  give the local conserved quantities. The density is given by

give the local conserved quantities. The density is given by

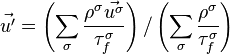

and the weighted average velocity,  , and the local momentum are given by

, and the local momentum are given by

In the above equation for the equilibrium velocity  , the

, the  term is the interaction force between a component and the other components. It is still the subject of much discussion as it is typically a tuning parameter that determines how fluid-fluid, fluid-gas, etc. interact. Frank et al. list current models for this force term. The commonly used derivations are Gunstensen chromodynamic model, Swift's free energy-based approach for both liquid/vapor systems and binary fluids, He's intermolecular interaction-based model, the Inamuro approach, and the Lee and Lin approach.[12]

term is the interaction force between a component and the other components. It is still the subject of much discussion as it is typically a tuning parameter that determines how fluid-fluid, fluid-gas, etc. interact. Frank et al. list current models for this force term. The commonly used derivations are Gunstensen chromodynamic model, Swift's free energy-based approach for both liquid/vapor systems and binary fluids, He's intermolecular interaction-based model, the Inamuro approach, and the Lee and Lin approach.[12]

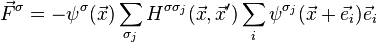

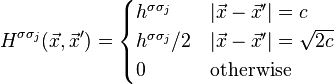

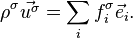

The following is the general description for  as given by several authors.[13][14]

as given by several authors.[13][14]

is the effective mass and

is the effective mass and  is Green's function representing the interparticle interaction with

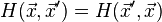

is Green's function representing the interparticle interaction with  as the neighboring site. Satisfying

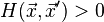

as the neighboring site. Satisfying  and where

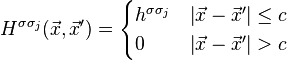

and where  represents repulsive forces. For D2Q9 and D3Q19, this leads to

represents repulsive forces. For D2Q9 and D3Q19, this leads to

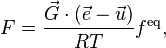

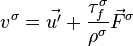

The effective mass as proposed by Shan and Chen uses the following effective mass for a single-component, multiphase system. The equation of state is also given under the condition of a single component and multiphase.

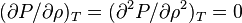

So far, it appears that  and

and  are free constants to tune but once plugged into the system's equation of state(EOS), they must satisfy the thermodynamic relationships at the critical point such that

are free constants to tune but once plugged into the system's equation of state(EOS), they must satisfy the thermodynamic relationships at the critical point such that  and

and  . For the EOS,

. For the EOS,  is 3.0 for D2Q9 and D3Q19 while it equals 10.0 for D3Q15.[15]

is 3.0 for D2Q9 and D3Q19 while it equals 10.0 for D3Q15.[15]

It was later shown by Yuan and Schaefer[16] that the effective mass density needs to be changed to simulate multiphase flow more accurately. They compared the Shan and Chen (SC), Carnahan-Starling (C–S), van der Waals (vdW), Redlich–Kwong (R–K), Redlich–Kwong Soave (RKS), and Peng–Robinson (P–R) EOS. Their results revealed that the SC EOS was insufficient and that C–S, P–R, R–K, and RKS EOS are all more accurate in modeling multiphase flow of a single component.

For the popular isothermal lattice Boltzmann methods these are the only conserved quantities. Thermal models also conserve energy and therefore have an additional conserved quantity:

Applications

During the last years, the LBM has proven to be a powerful tool for solving problems at different length scales. The behavior of fluid flow through porous media can be analyzed using the lattice Boltzmann method. LBM has been applied to: - Earth sciences (Soil filtration). - Energy Sciences (Fuel Cells[17]).

Software

Open Source / free software

- Advanced Simulation Library:[18] Open source (AGPLv3) hardware accelerated multiphysics simulation software that utilizes LBM and supports, i.a., CPUs, GPUs, DSPs, FPGAs; (C++ API, internal engine in OpenCL).

- AeroDoodle: WebGL based lattice Boltzmann implementation. Developed as a tool for teaching aerodynamics.

- Blender: Open Source 3D modeler that uses LBM in fluid simulation (http://wiki.blender.org/index.php/Doc:2.6/Manual/Physics/Fluid/Technical_details) models (multi-component, turbulence modeling)

- C examples: Some simple example LBM code in C (GPL).

- El'Beem: free CFD code (GPL) which uses LBM

- J-Lattice-Boltzmann: interactive Java applet for experimenting with LBM

- LBM-C: Open Source (GPLv2) CUDA code

- LIMBES: Open source (GPL) code in 2D based on Gauss-Hermite quadrature, parallel (openmp), fortran 90

- Mechsys: Open source code includes lattice Bolztmann and several other numerical methods in C++.

- OpenLB: Open source (GPLv2) library based on LBM, parallel, C++

- Palabos: Open source (AGPL) parallel C++ code with a large spectrum of lattice Boltzmann models, including thermal, multi-phase, free-surface, and embedded particles.

- Sailfish: Open Source LBM code (LGPL) for Graphics Processing Units (CUDA/OpenCL), with support for distributed multi-GPU simulations and various lattice Boltzmann

- Taxila LBM: Open source (LGPL) lattice Boltzmann code from Los Alamos Natl. Lab, parallel, F90, multi-component/multi-phase/2D & 3D.

Freeware

- LBSim: software written in C++, freely available

Commercial

- M-Star: Time-accurate, DNS/LES multi-physics package. Tailored for mixing and reactor modeling.

- LaBS: LaBS or Lattice Boltzmann Solver is a commercial CFD code based on the lattice Boltzmann Method. It is developed within the framework of a consortium including Renault, Airbus and CS Communication et Systèmes. CS Communication et Systèmes is in charge of distributing the software.

- LBHydra: LBHydra is a modular, extensible Lattice-Boltzmann simulation package capable of modeling laminar and turbulent flows, heat and mass transport, and multiple phase and multiple component fluids in complex and changing fluid flow 2D & 3D geometries. Parallel, C++/CUDA code. University of Minnesota.

- PowerFLOW: commercial CFD code which uses LBM, created and distributed by Exa Corp.

- FlowKit: Professional support for the open-source software Palabos.

- XFlow: recent commercial CFD code based on LBM, released by Next Limit Technologies

- ultraFluidX: commercial CFD code based on LBM with multi-GPU support, released by FluiDyna GmbH FluiDyna.

Further reading

- Deutsch, Andreas and Sabine Dormann (2004). Cellular Automaton Modeling of Biological Pattern Formation. Birkhäuser Verlag. ISBN 978-0-8176-4281-5.

- Succi, Sauro (2001). The Lattice Boltzmann Equation for Fluid Dynamics and Beyond. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-850398-9.

- Wolf-Gladrow, Dieter (2000). Lattice-Gas Cellular Automata and Lattice Boltzmann Models. Springer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-66973-9.

- Sukop, Michael C. and Daniel T. Thorne, Jr. (2007). Lattice Boltzmann Modeling: An Introduction for Geoscientists and Engineers. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-27981-5.

- Jian Guo Zhou (2004). Lattice Boltzmann Methods for Shallow Water Flows. Springer. ISBN 3-540-40746-4.

- He,X., Chen, S., Doolen, G. (1998). A Novel Thermal Model for the Lattice Boltzmann Method in Incompressible Limit. Academic Press.

- Guo, Z. L., and Shu, C (2013). Lattice Boltzmann Method and Its Applications in Engineering. World Scientific Publishing.

Notes

- ↑ Succi, p. 68

- ↑ Succi, Appendix D (p. 261-262)

- ↑ Succi, chapter 8.3, p. 117-119

- ↑ Di Rienzo, A. Fabio; Asinari, Pietro; Chiavazzo, Eliodoro; Prasianakis, Nikolaos; Mantzaras, John (2012). "Lattice Boltzmann model for reactive flow simulations". EPL 98: 34001. Bibcode:2012EL.....9834001D. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/98/34001.

- ↑ Chiavazzo, Eliodoro; Karlin, Ilya; Gorban, Alexander; Boulouchos, Konstantinos (2010). "Coupling of the model reduction technique with the lattice Boltzmann method for combustion simulations". Combust. Flame 157: 1833–1849. doi:10.1016/j.combustflame.2010.06.009.

- ↑ Chiavazzo, Eliodoro; Karlin, Ilya; Gorban, Alexander; Boulouchos, Konstantinos (2012). "Efficient simulations of detailed combustion fields via the lattice Boltzmann method". International Journal of Numerical Methods for Heat & Fluid Flow 21: 494–517. doi:10.1108/09615531111135792.

- ↑ Chiavazzo, Eliodoro; Karlin, Ilya; Gorban, Alexander; Boulouchos, Konstantinos (2009). "Combustion simulation via lattice Boltzmann and reduced chemical kinetics". Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment 2009: P06013. Bibcode:2009JSMTE..06..013C. doi:10.1088/1742-5468/2009/06/P06013.

- ↑ McNamara, G., Garcia, A., and Alder, B., "A hydrodynamically correct thermal lattice boltzmann model", Journal of Statistical Physics, vol. 87, no. 5, pp. 1111-1121, 1997.

- ↑ Shan, X., "Simulation of rayleigh-b'enard convection using a lattice boltzmann method", Physical Review E, vol. 55, pp. 2780-2788, The American Physical Society, 1997.

- ↑ He, X., Chen, S., and Doolen, G.D., "A novel thermal model for the lattice boltzmann method in incompressible limit", Journal of Computational Physics, vol. 146, pp. 282-300, 1998.

- ↑ Chen, S., and Doolen, G. D., "Lattice Boltzmann Method for Fluid Flows", Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics, vol. 30, p. 329–364, 1998.

- ↑ Frank, X., Almeida, G., Perre, P., "Multiphase flow in the vascular system of wood: From microscopic exploration to 3-D Lattice Boltzmann experiments", International Journal of Multiphase Flow, vol. 36, pp. 599-607, 2010.

- ↑ Yuan, P., Schaefer, L., "Equations of State in a lattice Boltzmann model", Physics of Fluids, vol. 18, 2006.

- ↑ Harting, J., Chin, J., Maddalena, V., Coveney, P., "Large-scale lattice Boltzmann simulations of complex fluids: advances through the advent of computational Grids", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, vol. 363, pp. 1895–1915 2005.

- ↑ Yuan, P., Schaefer, L., "A Thermal Lattice Boltzmann Two-Phase Flow Model and its Application to Heat Transfer Problems-Part 1. Theoretical Foundation", Journal of Fluid Engineering 142-150, vol. 128, 2006.

- ↑ Yuan, P.; Schaefer, L. (2006). "Equations of State in a lattice Boltzmann model". Physics of Fluids 18: 042101. doi:10.1063/1.2187070.

- ↑ Link text, Espinoza, M., Andersson, M., Yuan, J., and Sundén, B. (2015) Compress effects on porosity, gas-phase tortuosity, and gas permeability in a simulated PEM gas diffusion layer. Int. J. Energy Res., 39: 1528–1536. doi: 10.1002/er.3348..

- ↑ "Advanced Simulation Library".

External links

- OpenLB: LBM community forum for discussions on research, implementation, open positions and upcoming conferences, ..

- palabos.org: A site with various resources related to LBM, including a forum.

- LBM Method

- Lattice Boltzmann summary

- Erlangen Lattice Boltzmann mailing list

- Entropic Lattice Boltzmann Method (ELBM)

- DSFD mailing list: sends information about DSFD and related conferences, opportunities for doctoral, postdoctoral, faculty and industry positions for applicants who have experience with Lattice Boltzmann or other related methods.

- dsfd.org: Website of the annual DSFD conference series (1986 -- now) where advances in theory and application of the lattice Boltzmann method are discussed

- Website of the annual ICMMES conference on Lattice Boltzmann methods and their applications

![\frac{\part f_i^\text{eq}}{\part t_2} + \left( 1 - \frac{1}{2\tau} \right) \left[ \frac{\part f_i^{(1)}}{\part t_1} + \vec{e}_i \nabla_1 f_i^{(1)} \right] = -\frac{f_i^{(2)}}{\tau}.](../I/m/16bf9a88e715b3a951dd95eac67ed91b.png)

![\Pi_{xy} = \sum_{i}\vec{e}_{ix}\vec{e}_{iy} \left[ f_i^{eq} + \left( 1 - \frac{1}{2 \tau} \right) f_i^{(1)} \right],](../I/m/a47724efa92430b38138d00e53f57f5c.png)

![\psi(\vec{x})=\psi(\rho^{\sigma})=\rho_0^{\sigma}\left[1-e^{(-\rho^{\sigma}/\rho_0^{\sigma})} \right]\,\!](../I/m/57b3ae3d3ecc0fc46a619025f6ff495a.png)

![p=c_s^2 \rho+c_0h[\psi(\vec{x})]^2\,\!](../I/m/b688ac1ca667fb9a4f72885d279737e0.png)