Latakia

| Latakia اللَاذِقِيَّة Al-Lādhiqīyah | ||

|---|---|---|

|

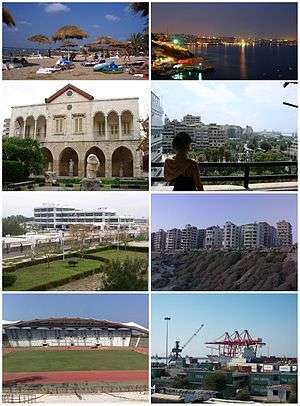

Latakia Cote d'Azur beach • Latakia skyline Museum of Latakia • Downtown Latakia Tishreen University • Latakia Corniche Latakia Sports City Stadium • Port of Latakia | ||

| ||

Latakia Location in Syria | ||

| Coordinates: 35°31′N 35°47′E / 35.517°N 35.783°E | ||

| Country |

| |

| Governorate | Latakia Governorate | |

| District | Latakia District | |

| Government | ||

| • Governor | Ahmad Sheikh Abdulqader[1] | |

| Area | ||

| • Land | 58 km2 (22 sq mi) | |

| • Metro | 108 km2 (42 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 11 m (36 ft) | |

| Population (2004 census) | ||

| • City | 383,786[2] | |

| • Metro | 424,392 | |

| Area code(s) | 41 | |

| Climate | Csa | |

| Website | eLatakia | |

Latakia; Lattakia or Latakiyah (Arabic: اللَاذِقِيَّة al-Lādhiqīyah Syrian pronunciation: [el.laːdˈʔɪjje, -laːðˈqɪjja]), is the principal port city of Syria, as well as the capital of the Latakia Governorate. Historically, it has also been known as Laodicea or Laodicea ad Mare. In addition to serving as a port, the city is a manufacturing center for surrounding agricultural towns and villages. According to the 2004 official census, the population of the city is 383,786.[3][4] It is the 5th-largest city in Syria after Aleppo, Damascus, Homs and Hama, and it borders Tartus to the south, Hama to the east, and Idlib to the north.

Although the site has been inhabited since the 2nd millennium BCE, the modern-day city was first founded in the 4th century BCE under the rule of the Seleucid empire. Latakia was subsequently ruled by the Romans, then the Ummayads and Abbasids in the 8th–10th centuries CE. Under their rule, the Byzantines frequently attacked the city, periodically recapturing it before losing it again to the Arabs, particularly the Fatimids. Afterward, Latakia was ruled successively by the Seljuk Turks, Crusaders, Ayyubids, Mamluks, and Ottomans. Following World War I, Latakia was assigned to the French mandate of Syria, in which it served as the capital of the autonomous territory of the Alawites. This autonomous territory became the Alawite State in 1922, proclaiming its independence a number of times until reintegrating into Syria in 1944.

Etymology

Like many Seleucid cities, Latakia was named after a member of the ruling dynasty.[5] First named Laodikeia on the Coast (Greek: Λαοδίκεια ἡ Πάραλος) by Seleucus I Nicator in honor of his mother, Laodice. In Latin, its name became Laodicea ad Mare. The original name survives in its Arabic form as al-Ladhiqiyyah (Arabic: اللاذقية), from which the French Lattaquié and English Latakia or Lattakia derive.[5][6] To the Ottomans, it was known as Turkish: Lazkiye.

History

Ancient settlement and founding

The location of Latakia, the Ras Ziyarah promontory,[7][8] has a long history of occupation. The Phoenician city of Ramitha was located here, known to the Greeks as Leukê Aktê ("white coast").

The city was described in Strabo's Geographica:[9]

"It is a city most beautifully built, has a good harbour, and has territory which, besides its other good crops, abounds in wine. Now this city furnishes the most of the wine to the Alexandreians, since the whole of the mountain that lies above the city and is possessed by it is covered with vines almost as far as the summits. And while the summits are at a considerable distance from Laodicea, sloping up gently and gradually from it, they tower above Apameia, extending up to a perpendicular height."

Roman rule

The city was an important colonia of the Roman empire in ancient Syria for seven centuries. It was called Laodicea in Syria or "Laodicea ad mare" and was the capital of the Eastern Roman province of Theodorias from 528 AD until 637 AD. A sizable Jewish population lived in Laodicea during the first century.[10] The heretic Apollinarius was bishop of Laodicea in the 4th century. The city minted coins from an early date.

Crusader, Ayyubid, and Mamluk rule

After failed efforts by Bohemond I of Antioch to capture Latakia from the Byzantine Empire the city was taken in 1103 by forces under the command of Tancred of Hauteville, a veteran of the First Crusade and acting regent of the Principality of Antioch.[11] Following the defeat of Antiochene forces at the Battle of Harran in 1104 the city was reoccupied by the Byzantines however they would again lose the city. Despite a treaty in 1108 with Bohemond promising to return Latakia to the Empire by 1110 it was firmly under the control of the Principality of Antioch.[12] This would remain the case with the city serving as the primary port for the Principality until after the loss of Antioch itself to the Mamluks.[13]

In circa 1300, Arab geographer al-Dimashqi noted that Latakia had no running water and that trees were scarce, but the city's port was "a wonderful harbor... full of large ships".[14] In 1332, the Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta visited Latakia in his journeys.[15]

Ottoman rule

In 1888, when Wilayat Beirut was established, Latakia became its northernmost town.[16]

In the Ottoman period, the region of Latakia became predominantly Alawi. The Turkmen also consisted a significant minority. The city itself, however, contained significant numbers of Sunni and Christian inhabitants. The landlords in the countryside tended to be Sunni, while the peasants were mostly Alawi. Like the Druzes, who also had a special status before the end of World War I, the Alawis had a strained relationship with the Ottoman overlords. In fact, they were not even given the status of millet, although they enjoyed relative autonomy.[17]

French Mandate period

In 1920, Latakia fell under the French mandate, under which the Alawite State was established. The state lasted until 1936 when it was merged with the Syrian Republic.

Modern era

All but a few classical buildings have been destroyed, often by earthquakes; those remaining include a Roman triumphal arch and Corinthian columns known as the Colonnade of Bacchus.[18]

An extensive port project was proposed in 1948, and construction work began on the Port of Latakia in 1950, aided by a US$6 million loan from Saudi Arabia. By 1951, the first stage of the construction was completed, and the port handled an increasing amount of Syria's overseas trade.

In August 1957, 4,000 Egyptian troops landed in Latakia under orders from Gamal Abdel Nasser after Turkish troops massed along the border with Syria, accusing it of harboring Turkish Communists.[19]

A major highway linked Latakia with Aleppo and the Euphrates valley in 1968 and was supplemented by the completion of a railway line to Homs. The port became even more important after 1975, due to the troubled situation in Lebanon and the loss of Beirut and Tripoli as ports.[20]

In 1973, during the October War (Yom Kippur War), the naval Battle of Latakia between Israel and Syria was fought just offshore from Latakia. The battle was the first to be fought using missiles and ECM (electronic countermeasures).[21]

Syrian Civil War

During the Syrian Civil War, Latakia had been a site of protest activity since March 2011. The Syrian government claimed 12 were killed there in clashes in late March,[22] leading to the deployment of the military to restrict movement into and out of the city. Hundreds of Syrians were reportedly arrested, and by late July, activists in Latakia were telling foreign media they feared a more violent crackdown was coming. Protests continued despite the increased security presence and arrests. Several civilians were allegedly killed in confrontations with security officers during this early period of the siege.[23] On 13 August 2011, the Syrian Army and Syrian Navy launched an operation where more than 20 tanks and APCs rolled into the Alawi stronghold.[24] The city was also attacked by the Syrian army on the 14 August 2011. Activists claimed that 25 people died during the attack.[25]

Latakia is the home of Russia's largest foreign electronic eavesdropping facility.[26] Khmeimim Air Base is an airbase near Latakia converted to use by the Russian military in 2015. On 24 November 2015, Turkish forces shot down a Russian fighter plane over Latakia. One pilot was killed and the other rescued by Syrian military and brought to Khmeimim.[27][28]

Geography

Latakia is located 348 kilometres (216 mi) north-west of Damascus, 186 kilometres (116 mi) south-west from Aleppo, 186 kilometres (116 mi) north-west of Homs, and 90 kilometres (56 mi) north of Tartus.[29] Nearby towns and villages include Kasab to the north, Al-Haffah, Deirmama, Slinfah and Qardaha to the east in the al-Ansariyah mountain range, and Jableh and Baniyas to the south.

Latakia is the capital of the Latakia Governorate, in western Syria, bordering Turkey to the north. The governorate has a reported area of either 2,297 square kilometres (887 sq mi)[30] or 2,437 square kilometres (941 sq mi).[31] Latakia city is located in the Latakia District in the northern portion of Latakia governorate.

Climate

Under Köppen's climate classification, Latakia has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Csa).[32] Latakia's wettest months are December and January, where average precipitation is around 160 mm. The city's driest month, July, only has on average about 1 millimetre (0.039 in) of rain. Average high temperatures in the city range from around 16 °C (61 °F) in January to around 30 °C (86 °F) in August. Latakia on average receives around 760 millimetres (30 in) of rainfall annually. Although rare in winter, snow can fall mixed with rain or by itself as light snow.

| Climate data for Latakia (1966-2004) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 15.6 (60.1) |

16.3 (61.3) |

18.4 (65.1) |

21.5 (70.7) |

24.2 (75.6) |

26.8 (80.2) |

28.9 (84) |

29.7 (85.5) |

29.0 (84.2) |

26.8 (80.2) |

22.1 (71.8) |

17.3 (63.1) |

23.05 (73.48) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 8.4 (47.1) |

9.0 (48.2) |

10.9 (51.6) |

14.0 (57.2) |

17.1 (62.8) |

20.9 (69.6) |

24.0 (75.2) |

24.5 (76.1) |

22.1 (71.8) |

18.4 (65.1) |

13.7 (56.7) |

10.0 (50) |

16.08 (60.95) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 162.6 (6.402) |

99.8 (3.929) |

90.6 (3.567) |

44.2 (1.74) |

21.0 (0.827) |

4.5 (0.177) |

0.9 (0.035) |

4.5 (0.177) |

7.8 (0.307) |

67.1 (2.642) |

95.2 (3.748) |

160.7 (6.327) |

758.9 (29.878) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 13 | 17 | 11 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 13 | 83 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 136.4 | 153.7 | 198.4 | 225 | 297.6 | 321 | 325.5 | 316.2 | 288 | 248 | 192 | 151.9 | 2,853.7 |

| Source #1: World Meteorological Organization,[33] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Hong Kong Observatory for sunshine hours[34] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

.jpg)

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1905 | 25,000[35] |

| 1932 | 24,000[36] |

| 1943 | 36,000[36] |

| 1957 | 56,000[36] |

| 1970 | 126,000[36] |

| 1987 | 241,000[36] |

| 1994 | 303,000[36] |

One of the first censuses was in 1825, which recorded that there were 6,000-8,000 Muslims, 1,000 Greek Orthodox Christians, 30 Armenian Christians, 30 Maronite Catholics, and 30 Jews.[37] At the beginning of the 20th century, Latakia had a population of roughly 7,000 inhabitants; however, the Journal of the Society of Arts recorded a population of 25,000 in 1905.[35] In a 1992 estimate, Latakia had a population of 284,000,[38] rising to 303,000 in the 1994 census.[36] The city's population continued to rise, reaching an estimated 402,000 residents in 2002.[39]

Latakia was a historically Sunni city until the 1970s when Alawites, encouraged by the then President Hafez Al Asaad settled in the city and by the 1980s, Alawites formed a majority. By 2010 estimates, the city of Latakia is 50% Alawite, 40% Sunni and 10% Christian.[40] The rural hinterland has an Alawite majority of roughly 70%, with Christians making up 14%, Sunni Muslims making up 12%, and Ismailis representing the remaining 2%. The city serves as the capital of the Alawite population and is a major cultural center for the religion.[39] Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, large numbers of Alawites from the area emigrated to the country's capital Damascus.[41] Of the Christians, a sizable Antiochian Greek population exists in Latakia, and their diocese in the city has the largest congregation of the Greek Orthodox Church of Antioch.[42][43][44] There is also an Armenian community of 3,500 in the city.[44][45] The entire population speaks Arabic, mostly in the North Levantine dialect.[46]

Within the city boundaries is the "unofficial" Latakia camp, established in 1956, which has a population of 6,354 Palestinian refugees, mostly from Jaffa and the Galilee.[47]

Economy

Latakia has an extensive agricultural hinterland. Exports include bitumen (asphalt), cereals, cotton, fruits, eggs, vegetable oil, pottery, and tobacco. Cotton ginning, vegetable-oil processing, tanning, and sponge fishing serve as local industries for the city.[18]

The Cote d'Azur Beach of Latakia is Syria's premier coastal resort, and offers water skiing, jet skiing, and windsurfing. The city contains eight hotels, two of which have five-star ratings; both the Cote d'Azur de Cham Hotel and Lé Meridien Lattiquie Hotel are located 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) north of the city, at Cote d'Azur. The latter hotel has 274 rooms and is the only international hotel in the city.[48]

Compared to other Syrian cities, window shopping and evening strolls in the markets is considered a favorite pastime in Latakia. Numerous designer-label stores line 8 Azar Street, and the heart of the city's shopping area is the series of blocks enclosed by 8 Azar Street, Yarmouk Street, and Saad Zaghloul Street in the city center. Cinemas in Latakia include Ugarit Cinema, al-Kindi, and a smaller theater off al-Moutanabbi Street.[49]

Culture

Festivals

Museums

The National Museum of Latakia was built in 1986 near the seafront of the city. It formerly housed the residence of the Governor of the Alawite State and was originally a 16th-century Ottoman khan ("caravansary") known as Khan al-Dukhan, meaning "The Khan of Smoke", as it served the tobacco trade. The khan historically served not only as an inn, but also contained private residences.[42] The exhibits include inscribed tablets from Ugarit, ancient jewellery, coins, figurines, ceramics, pottery, and early Arab and Crusader-era chain-mail suits and swords.[50][51]

Sport

Latakia is the home city of two football clubs: Teshrin Sports Club was founded in 1947,[52] and Hutteen Sports Club was founded in 1945.[53] Both teams are based in the al-Assad Stadium, which carries a capacity of 35,000 people. Just north of the city is the Latakia Sports City complex, which was built in 1987 to host the 1987 Mediterranean Games.[54]

Latakia tobacco

Latakia tobacco is a specially prepared tobacco originally produced in Syria and named after the port city of Latakia.[55] Now the tobacco is mainly produced in Cyprus. It is cured over a stone pine or oak wood fire, which gives it an intense smokey-peppery taste and smell. Rarely smoked straight, it is used as a "condiment" or "blender" (a basic tobacco mixed with other tobaccos to create a blend), especially in English, Balkan, and some American Classic blends.[55]

Education

The University of Latakia was founded in 1971 and renamed Tishreen University ("October University") in 1976 to commemorate the victory Syria claimed in the October War of 1973. The university has an enrollment of 25,660 students, 57% of which are females.[56] The city houses a branch of the Arab Academy for Science and Technology and Maritime Transport.[18]

A school in Latakia, Syria is named after Jules Jammal, an Arab Christian military officer who blew himself up in a suicide attack on a French ship.[57]

Local infrastructure

Landmarks

The modern city still exhibits faint traces of its former importance, notwithstanding the frequent earthquakes with which it has been visited. The marina is built upon foundations of ancient columns, and there are in the town an old gateway and other antiquities, as also sarcophagi and sepulchral caves in the neighbourhood. This gateway is a remarkable triumphal arch at the southeast corner of the town, almost entire: it is built with four entrances, like the Forum Jani at Rome. It is conjectured that this arch was built in honour of Lucius Verus, or of Septimius Severus.[58] Fragments of Greek and Latin inscriptions are dispersed all over the ruins, but entirely defaced.

Notable points of interest in the nearby area include the massive Saladin's Castle and the ruins of Ugarit, where some of the earliest alphabetic writings have been found. There are also several popular beaches. There are numerous mosques in Latakia, including the 13th-century Great Mosque and the 18th-century Jadid Mosque constructed by Suleiman Pasha Azem.[42]

Latakia has consulates general of Finland and France, and honorary consulates of Greece and Romania.

Transportation

Roads link Latakia to Aleppo, Beirut, Homs, and Tripoli.[18] The main commercial coastal road of the city is Jamal Abdel Nasser Street, named after former Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser. Lined with hotels, restaurants and the city museum, the street begins in central Latakia along the Mediterranean coast and ends at Hitteen Square. From the square, it branches southwest into al-Maghreb al-Arabi Street,[59] south into 8 Azar Street, which continues south to form Baghdad Avenue—the main north-south road[60]—branching into Beirut Street and Nadim Hassan Street along the southern coastline. From the southern portion of Jamal Abdel Nasser Street branch off al-Yarmouk Street and al-Quds Street, the latter which ends at al-Yaman Square in western Latakia, it continues west into Abdel Qader al-Husseini Street. North from al-Yaman Square Souria Avenue and south of the square is al-Ourouba Street. Souria Avenue ends in al-Jumhouriah Square, then continues north as al-Jumhouriah Street.[59]

Much of the city is accessible by taxi and other forms of public transportation. Buses transport people to various Syrian, Lebanese, and Turkish cities, including Aleppo, Damascus, Deir ez-Zor, Palmyra, Tripoli, Beirut, Safita, Hims, Hama, Antakya, and Tartous. The "luxury" Garagat Pullman Bus Station is located on Abdel Qader al-Husseini Street, and at least a dozen private companies are based at the station. On the same street is the older Hob-Hob Bus Station that operates a "depart when full" basis to Damascus and Aleppo. Local microbuses run between al-Yaman Square and the city center, as well as between the station on al-Jalaa Street and the city center. There is also a microbus station with buses departing to Qalaat Salah ed-Din, Qardaha, Kassab, and Jableh.[49]

Latakia's train station is located on al-Yaman Square. Chemins de Fer Syriens operated services, including two daily runs to Aleppo and one weekly run to Damascus via Tartous. In 2005, approximately 512,167 passengers departed from Latakia's train station.[61]

The Bassel Al-Assad International Airport is located 25 kilometers (16 mi) south of Latakia and serves as a national and regional airport with regular flights to Sharjah, Jeddah, Riyadh and Cairo. The Port of Latakia is also a link in six organized cruises between Alexandria, İzmir and Beirut. In addition, there are irregular ferry services to Cyprus. In 2005, approximately 27,939 passengers used the port.[61]

International relations

Twin towns – Sister cities

-

Sousse, Tunisia

Sousse, Tunisia -

Mersin, Turkey[62]

Mersin, Turkey[62] -

Constanţa, Romania

Constanţa, Romania -

Rimini, Italy

Rimini, Italy -

Gilan Province, Iran[63]

Gilan Province, Iran[63] -

Genoa, Italy

Genoa, Italy

See also

References

- ↑ H. Zain / Mazen / H. Sabbagh (23 April 2011). "New Governor of Lattakia sworn in". Syrian Arab News Agency. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ↑ Latakia city population

- ↑

- ↑ City population size reported at "World-Gazetteer.com". Archived from the original on 2013-02-10.. Similarly reported by CityPopulation.de.

- 1 2 le Strange, 1890, p.380.

- ↑ Ball, 2000, p.157

- ↑ "Ras Ziyarah", literally, "Cape of Visitation (Ziyarah)"

- ↑ "Prostar Sailing Directions 2005 Eastern Mediterranean Enroute", p. 38. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=elzyK_4aWPUC&pg=PA38&dq=%22Ras+Ziyarah%22&hl=en&ei=iERNTsi6LeTjiALsv_WIAQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCoQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=%22Ras%20Ziyarah%22&f=false.

- ↑ Strabo (1857), The Geography of Strabo, p. 164, ISBN 0-521-85306-0

- ↑ Laodicea, Jewish Encyclopedia, archived from the original on November 15, 2007, retrieved 2009-03-01

- ↑ Thomas Asbridge, The Crusades: The War for the Holy Land, (London: Simon & Schuster, 2010), pp.137-138.

- ↑ Thomas Asbridge, The Crusades: The War for the Holy Land, (London: Simon & Schuster, 2010), pp.137-144.

- ↑ Thomas Asbridge, The Crusades: The War for the Holy Land, (London: Simon & Schuster, 2010), p.637.

- ↑ al-Dimashqi quoted in le Strange, 1890, p.491.

- ↑ The adventures of Ibn Battuta, a Muslim traveler of the fourteenth century By Ross E. Dunn, University of California Press. pp.137.

- ↑ Dumper, 2007, p.84

- ↑ Rabinovich, 1979, p.694

- 1 2 3 4 Latakia. (2009). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2009-03-01, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ↑ Podeh 1999, pp. 43

- ↑ Ring, 1994, p.455

- ↑ Betts, Richard K. (1982), Cruise Missile: Technology, Strategy and Politics, Brookings Institution Press, p. 381, ISBN 0-8157-0931-5

- ↑ "Twelve killed in Saturday’s Latakia protests, presidential adviser says". NOW Lebanon. 27 March 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ↑ "SYRIA: Protesters in Lattakia brave security forces". The Los Angeles Times. 25 July 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ↑ "Syrian army 'enters western coastal city'". Al Jazeera English. 13 August 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ↑ "Syrian 'warships shell port city of Latakia'". Al Jazeera. 14 Aug 2011.

- ↑ Russian military presence in Syria poses challenge to US-led intervention The Guardian, 2012-12-23.

- ↑ "Turkey shoots down Russian warplane on Syria border". BBC News. 25 November 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ↑ "СМИ: второй пилот сбитого Су-24 был эвакуирован сирийскими военными" [Media: Second pilot of downed Su-24 was evacuated by Syrian military]. Gazeta.ru (in Russian). 25 November 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ↑ Distance Between Main Syrian Cities, HomsOnline, 2008-05-16, retrieved 2009-02-26

- ↑ Syria, citypopulation.de, 2008, retrieved 2009-08-10

- ↑ Provinces of Syria, Statoids, 2005, retrieved 2009-08-10

- ↑ http://www.hydrol-earth-syst-sci.net/11/1633/2007/hess-11-1633-2007.pdf

- ↑ World Weather Information Service - Latakia, World Meteorological Organization, 2009, retrieved 2009-03-02

- ↑ "Climatological Information for Latakia, Syria". Hong Kong Observatory. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- 1 2 Society of Arts (Great Britain), 1906, p.556.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Winckler, 1998, p.72.

- ↑ American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, 1825, p.375.

- ↑ Latakia, Damascus-Online, archived from the original on December 31, 2009, retrieved 2009-07-29

- 1 2 Minahan, 2002, p.79.

- ↑ http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/latakia-is-assads-achilles-heel

- ↑ Dumper, 2007, pp.126-127.

- 1 2 3 Latakia Come to Syria.

- ↑ Fahlbusch and Bromiley, 2008, p.279.

- 1 2 Relations with Syria: The Greek community, Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2008, archived from the original on May 7, 2008, retrieved 2009-02-26

- ↑ The Armenian Prelacy in Aleppo, Periotem, retrieved 2009-03-01

- ↑ Minahan, 2002, p.80.

- ↑ Latakia:Unofficial Refugee Camp, UNRWA, 30 June 2002, retrieved 12 July 2007

- ↑ Carter, 2004, p.146.

- 1 2 Mannheim, 2001, pp.290-291.

- ↑ Carter, 2008, p.146.

- ↑ Historical Sites of Latakia Syria Gate.

- ↑ Teshrin SC Welt Fussball Archive.

- ↑ Al-Hutteen SC Welt Fussball Archive.

- ↑ Latakia Sports City Archnet Digital Library.

- 1 2 A Tale of Two Latakias, G. L. Pease Tobaccos, 2008, retrieved 2009-07-29

- ↑ http://lattakia.org/ShowArticle.aspx?ID=24

- ↑ AHMED FAWAZ La rencontre entre le Président et son second remonte à la fin des années quarante, sur les bancs du lycée Jules Jammal, dans la ville côtière de Lattaquié. Tous deux étaient membres du parti Baas. Cette rencontre n'était Le Nouvel Afrique Asie page 23

- ↑ Description of the East, vol. ii. p. 197.

- 1 2 Mannehim, 2001, p.284.

- ↑ Carter, 2004, p.144.

- 1 2 Transport, Latakia-city.gov.sy, 2008, retrieved 2009-03-10

- ↑ Mersin, Latakia become sister cities Turkish Daily News. 2008-01-21.

- ↑ "The Syrian-Iranian Joint Supreme Committee meetings (in Arabic)". Alwehda Publications. 2009-03-08. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

Bibliography

- Ball, Warwick (2000), Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire, Routledge, ISBN 9780415113762.

- Beattie, Andrew; Pepper, Timothy (2001), The Rough Guide to Syria, Rough Guides, ISBN 9781858287188

- Carter, Terry; Dunston, Lara; Humphreys, Andrew (2004), Syria & Lebanon, Lonely Planet, ISBN 9781864503333

- Carter, Terry; Dunston, Lara; Thomas, Amelia (2008), Syria & Lebanon, Lonely Planet, ISBN 9781741046090

- Dumper, Michael; Stanley, Bruce E.; Abu-Lughod, Janet L. (2007), Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 9781576079195.

- Fahlbusch, Erwin; Bromiley, Geoffrey William (2008), The Encyclopedia Of Christianity: Volume 5: Si-Z, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN 9780802824172.

- Hamilton, H.C.; Falconer, W., eds. (1857), The Geography of Strabo III, London: Henry G. Bohn.

- Maʻoz, Moshe; Yaniv, Avner; Gustav Heinemann Institute of Middle Eastern Studies (1986), Syria Under Assad: Domestic Constraints and Regional Risks, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-7099-2910-2.

- Mannheim, Ivan (2001), Syria & Lebanon Handbook: The Travel Guide, Footprint Travel Guides, ISBN 9781900949903

- Minahan, James (2002), Encyclopedia of the stateless nations: ethnic and national groups around the world, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 9780313323843.

- Oxford Business Group (2006), Emerging Syria 2006, Oxford Business Group, ISBN 9781902339443.

- Podeh, Elie (1999), The Decline of Arab Unity: The Rise And Fall of the United Arab Republic, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 1-84519-146-3

- Rabinovich, Itamar (1979), "The Compact Minorities and the Syrian State, 1918-45", Journal of Contemporary History 14 (4): 693–712, doi:10.1177/002200947901400407

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2005), The Crusades: A History, Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 9780826472700.

- Ring, Trudy; Salkin, Robert M.; La Boda, Sharon (1994), International Dictionary of Historic Places, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 9781884964039.

- le Strange, Guy (1890), Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500, Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund, ISBN 0-404-56288-4.

- Society of Arts (Great Britain) (1906), Journal of the Society of Arts 54, The Society.

- Winckler, Onn (1998), Demographic developments and population policies in Baʻathist Syria, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 1-902210-16-6

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Latakia. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Latakia. |

- elatakia The First Complete website for Latakia news and services

- Latakia news and services (Arabic)

- Tishreen University (English) (Arabic)

- Audio interview with Latakia resident about life in Latakia (English)

- Pictures from 2009

Coordinates: 35°31′N 35°47′E / 35.517°N 35.783°E

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|