Large igneous province

A large igneous province (LIP) is an extremely large accumulation of igneous rocks, including liquid rock (intrusive) or volcanic rock formations (extrusive), when hot magma extrudes from inside the Earth and flows out. The source of many or all LIPs is variously attributed to mantle plumes or to processes associated with plate tectonics.[1] Types of LIPs can include large volcanic provinces (LVP), created through flood basalt and large plutonic provinces (LPP).[2] Eleven distinct flood basalt episodes occurred in the past 250 million years, creating volcanic provinces, which coincided with mass extinctions in prehistoric times.[3] Formation depends on a range of factors, such as continental configuration, latitude, volume, rate, duration of eruption, style and setting (continental vs. oceanic), the preexisting climate state, and the biota resilience to change.[4]

Definition

In 1992 researchers first used the term large igneous province to describe very large accumulations—areas greater than 100,000 square kilometers (approximately the area of Iceland)—of mafic igneous rocks that were erupted or emplaced at depth within an extremely short geological time interval: a few million years or less.[5] Mafic, basalt sea floors and other geological products of 'normal' plate tectonics were not included in the definition.[6]

Types

The definition of LIP has been expanded and refined, and is still a work in progress. LIP is now frequently also used to describe voluminous areas of, not just mafic, but all types of igneous rocks. Sub-categorization of LIPs into large volcanic provinces (LVP) and large plutonic provinces (LPP), and including rocks produced by normal plate tectonic processes, has been proposed.[2]

Some LIPs are now intact, such the basaltic Deccan Traps in India, while others have been dismembered by plate tectonic motion, like the basaltic Central Atlantic Magmatic Province (CAMP)—parts of which are found in Brazil, eastern North America, and north-western Africa.

Motivations for study of LIPs

Large igneous provinces (LIPs) are created during short-lived igneous events resulting in relatively rapid and high-volume accumulations of volcanic and intrusive igneous rock. These events warrant study because:

- The study of LIPs has economic implications. Some workers associate them with trapped hydrocarbons. They are associated with economic concentrations of copper–nickel and iron.[7] They are also associated with formation of major mineral provinces including Platinum-Group Element (PGE) Deposits, and in the Silicic LIPs, silver and gold deposits.[6] Titanium and vanadium deposits are also found in association with LIPs.[8]

- Future LIP events may pose a hazard to human civilization. LIPs in the geological record have marked major changes in the hydrosphere and atmosphere, leading to major climate shifts and maybe mass extinctions of species.[6]

- Plate tectonic theory explains topography using interactions between the tectonic plates, as influenced by viscous stresses created by flow within the underlying mantle. Since the mantle is extremely viscous, the mantle flow rate varies in pulses which are reflected in the lithosphere by small amplitude, long wavelength undulations. Understanding how the interaction between mantle flow and lithosphere elevation influences formation of LIPs is important to gaining insights into past mantle dynamics.[9]

- LIPs have played a major role in continental breakup, continental formation, new crustal additions from the upper mantle, and supercontinent cycles.[9]

Large igneous province formation

Earth has an outer shell made of a number of discrete, moving tectonic plates floating on a solid convective mantle above a liquid core. The mantle's flow is driven by the descent of cold tectonic plates during subduction and the complementary ascent of plumes of hot material from lower levels. The surface of the earth reflects stretching, thickening and bending of the tectonic plates as they interact.[10]

Ocean-plate creation at upwellings, spreading and subduction are well accepted fundamentals of plate tectonics, with the upwelling of hot mantle materials and the sinking of the cooler ocean plates driving the mantle convection. In this model, tectonic plates diverge at mid-ocean ridges, where hot mantle rock flows upward to fill the space. Plate-tectonic processes account for the vast majority of Earth's volcanism.[11]

Beyond the effects of convectively driven motion, deep processes have other influences on the surface topography. The convective circulation drives up-wellings and down-wellings in Earth's mantle that are reflected in local surface levels. Hot mantle materials rising up in a plume can spread out radially beneath the tectonic plate causing regions of uplift.[10] These ascending plumes play an important role in LIP formation.

Formation characteristics

When created, LIPs often have an areal extent of a few million km² and volumes on the order of 1 million km³. In most cases, the majority of a basaltic LIP's volume is emplaced in less than 1 million years. One of the conundra of such LIPs' origins is to understand how enormous volumes of basaltic magma are formed and erupted over such short time scales, with effusion rates up to an order of magnitude greater than mid-ocean ridge basalts.

Formation theories

The source of many or all LIPs are variously attributed to mantle plumes, to processes associated with plate tectonics or to meteorite impacts.

Plume formation of LIPs

Although most of volcanic activity on Earth is associated with subduction zones or mid-oceanic ridges, there are significant regions of long-lived, extensive volcanism, known as hot spots, which are only indirectly related to plate tectonics. The Emperor Sea Mount chain, located on the Pacific plate, is one example, tracing millions of years of relative motion as the plate moves over the Hawaiian hot spot. Numerous hot spots of varying size and age have been identified across the world. These hot spots move slowly with respect to one another, but move an order of magnitude more quickly with respect to tectonic plates, providing evidence that they are not directly linked to tectonic plates.[11]

The origin of hotspots remains controversial. Hotspots that reach the Earth’s surface may have three distinct origins. The deepest probably originate from the boundary between the lower mantle and the core; roughly 15–20% have characteristics such as presence of a linear chain of sea mounts with increasing ages, LIPs at the point of origin of the track, low shear wave velocity indicating high temperatures below the current location of the track, and ratios of He3 to He4 which are judged consistent with a deep origin. Others such as the Pitcairn, Samoan and Tahitian hotspots appear to originate at the top of large, transient, hot lava domes (termed superswells) in the mantle. The remainder appear to originate in the upper mantle and have been suggested to result from the breakup of subducting lithosphere.[12]

Recent imaging of the region below known hot spots (e.g., Yellowstone and Hawaii) using seismic-wave tomography has produced mounting evidence that supports relatively narrow, deep-origin, convective plumes that are limited in region compared to the large-scale plate tectonic circulation in which they are imbedded. Images reveal continuous, but torturous vertical paths with varying quantities of elevated temperature material, particularly at elevations where crystallographic transformations are predicted to occur.[13]

Plate-related stress formation of LIPs

A major alternative to the plume model is a model in which ruptures are caused by plate-related stresses that fractured the lithosphere, allowing melt to reach the surface from shallow heterogeneous sources. The high volumes of molten material that form the LIPs is postulated to be caused by convection in the upper mantle, which is secondary to the convection driving tectonic plate motion.[14]

Early formed reservoir outpourings

It has been proposed that geochemical evidence supports an early-formed reservoir that survived in the Earth's mantle for about 4.5 billion years. Molten material is postulated to have originated from this reservoir, contributing the Baffin Island flood basalt ~60 million years ago. Basalts from the Ontong Java plateau show similar isotopic and trace element signatures proposed for the early-Earth reservoir.[15]

Meteorite-induced formation

Seven pairs of hotspots and LIPs located on opposite sides of the earth have been noted; analyses indicate this coincident antipodal location is highly unlikely to be random. The hotspot pairs include a large igneous province with continental volcanism opposite an oceanic hotspot. Oceanic impacts of large meteorites are expected to have high efficiency in converting energy into seismic waves. These waves would propagate around the world and reconverge close to the antipodal position; small variations are expected as the seismic velocity varies depending upon the route characteristics along which the waves propagate. As the waves focus on the antipodal position, they put the crust at the focal point under significant stress and are proposed to rupture it, creating antipodal pairs. When the meteorite impacts a continent, the lower efficiency of kinetic energy conversion into seismic energy is not expected to create an antipodal hotspot.[14]

A second impact-related model of hotspot and LIP formation has been suggested in which minor hotspot volcanism was generated at large-body impact sites and flood basalt volcanism was triggered antipodally by focused seismic energy [13,14]. This model has been challenged because impacts are generally considered seismically too inefficient [15], and the Deccan Traps of India were not antipodal to, and began erupting several Myr before, the end-Cretaceous Chicxulub impact in Mexico. In addition, no clear example of impact-induced volcanism, unrelated to melt sheets, has been confirmed at any known terrestrial crater.[14]

Classification

In 1992, Coffin and Eldholm initially defined the term "large igneous province" (LIP) as representing a variety of mafic igneous provinces with areal extent >1 x 105 km2 that represented "massive crustal emplacements of predominantly mafic (Mg- and Fe-rich) extrusive and intrusive rock, and originated via processes other than 'normal' seafloor spreading."[16][17][18] That original definition included continental flood basalts, oceanic plateaus, large dike swarms (the eroded roots of a volcanic province), and volcanic rifted margins. Most of these LIPs consist of basalt, but some contain large volumes of associated rhyolite (e.g. the Columbia River Basalt Group in the western United States); the rhyolite is typically very dry compared to island arc rhyolites, with much higher eruption temperatures (850 °C to 1000 °C) than normal rhyolites.

Since 1992 the definition of 'LIP' has been expanded and refined, and remains a work in progress. Some new definitions of the term 'LIP' include large granitic provinces such as those found in the Andes Mountains of South America and in western North America. Comprehensive taxonomies have been developed to focus technical discussions.

In 2008, Bryan and Ernst refined the definition to narrow it somewhat: "Large Igneous Provinces are magmatic provinces with areal extents >1 x 105 km2, igneous volumes >1 x 105 km3 and maximum lifespans of ∼50 Myr that have intraplate tectonic settings or geochemical affinities, and are characterised by igneous pulse(s) of short duration (∼1–5 Myr), during which a large proportion (>75%) of the total igneous volume has been emplaced. They are dominantly mafic, but also can have significant ultramafic and silicic components, and some are dominated by silicic magmatism." This definition places emphasis on the high magma emplacement rate characteristics of the LIP event and excludes seamounts, seamount groups, submarine ridges and anomalous seafloor crust.[19]

'LIP' is now frequently used to also describe voluminous areas of, not just mafic, but all types of igneous rocks. Sub-categorization of LIPs into Large Volcanic Provinces (LVP) and Large Plutonic Provinces (LPP), and including rocks produced by 'normal' plate tectonic processes, has been proposed. Further, the threshold to be included as a LIP has been lowered to >5x104 km2.[2] The working taxonomy, focused heavily on geochemistry, which will be used to structure examples below, is:

- Large igneous provinces (LIP)

- Large volcanic provinces (LVP)

- Large rhyolitic provinces (LRPs)

- Large andesitic provinces (LAPs)

- Large basaltic provinces (LBPs)

- Continental flood basalts

- Oceanic flood basalts

- Large basaltic–rhyolitic provinces (LBRPs)

- Large plutonic provinces (LPP)

- Large granitic provinces (LGP)

- Large mafic plutonic provinces

- Large volcanic provinces (LVP)

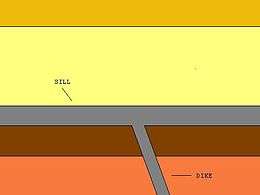

Aerally extensive dike swarms, sill provinces, and large layered ultramafic intrusions are indicators of LIPs, even when other evidence is not now observable. The upper basalt layers of older LIPs may have been removed by erosion or deformed by tectonic plate collisions occurring after the layer is formed. The is especially likely for earlier periods such as the Paleozoic and Proterozoic.[19]

Giant dyke swarms having lengths >300 km[20] are a common record of severely eroded LIPs. Both radial and linear dyke swarm configurations exist. Radial swarms with an areal extent >2000 km and linear swarms extending >1000 km are known. The linear dyke swarms often have a high proportion of dykes relative to country rocks, particularly when the width of the linear field is less than 100 km. The dykes have a typical width of 20–100 meters, although ultramafic dykes with widths greater than 1000 meters have been reported.[19]

Dykes are typically sub-vertical to vertical. When upward flowing (dyke-forming) magma encounters horizontal boundaries or weaknesses, such as between layers in a sedimentary deposit, the magma can flow horizontally creating a sill. Some sill provinces have areal extents >1000 km,[19]

Correlations with LIP formation

Correlation with hot-spots

The early volcanic activity of major hotspots, postulated to result from deep mantle plumes, is frequently accompanied by flood basalts. These flood basalt eruptions have resulted in large accumulations of basaltic lavas emplaced at a rate greatly exceeding that seen in contemporary volcanic processes. Continental rifting commonly follows flood basalt volcanism. Flood basalt provinces may also occur as a consequence of the initial hot-spot activity in ocean basins as well as on continents. It is possible to track the hot spot back to the flood basalts of a large igneous province; the table below correlates large igneous provinces with the track of a specific hot spot.[21][22]

| Province | Region | Hotspot | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Columbia River Basalt | Northwestern USA | Yellowstone hotspot | [21][23] |

| Afro-Arabia | Yemen-Ethiopia | [21] | |

| North Atlantic Igneous Province | Northern Canada, Greenland, the Faeroe Islands, Norway, Ireland and Scotland | Iceland hotspot | [21] |

| Deccan Traps | India & southern Pakistan | Réunion hotspot | [21] |

| Rahjamal Traps | Eastern India | Ninety East Ridge | [24][25] |

| Ontong-Java Plateau | Pacific Ocean | Louisville hotspot | [21][22] |

| Paraná and Etendeka traps | Brazil–Namibia | Tristan hotspot | [21] |

| Karoo-Ferrar Province | South Africa, Antarctica, Australia & New Zealand | Marion Island | [21] |

| Caribbean large igneous province | Caribbean-Colombian oceanic plateau | Galápagos hotspot | [26][27] |

| Mackenzie Large Igneous Province | Canadian Shield | Mackenzie hotspot | [28] |

Relationship to extinction events

Eruptions or emplacements of LIPs appear to have, in some cases, occurred simultaneously with oceanic anoxic events and extinction events. The most important examples are the Deccan Traps (Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event), the Karoo-Ferrar (Pliensbachian-Toarcian extinction), the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province (Triassic-Jurassic extinction event), and the Siberian traps (Permian-Triassic extinction event).

Several mechanisms are proposed to explain the association of LIPs with extinction events. The eruption of basaltic LIPs onto the earth's surface releases large volumes of sulfate gas, which forms sulfuric acid in the atmosphere; this absorbs heat and causes substantial cooling (e.g., the Laki eruption in Iceland, 1783). Oceanic LIPs can reduce oxygen in seawater by either direct oxidation reactions with metals in hydrothermal fluids or by causing algal blooms that consume large amounts of oxygen.[29]

Ore deposits

Large igneous provinces are associated with a handful of ore deposit types including:

Examples

There are a number of well documented examples of large igneous provinces identified by geological research.

| Province | Region | Age (Ma) | Area (106 km2 | Volume (106 km3 | Also known as or includes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agulhas Plateau | Southwest Indian Ocean, South Atlantic Ocean, Southern Ocean | 140-95 | 0.3 | 1.2 | Southeast African LIP Mozambique Ridge, Northeast Georgia Rise, Maud Rise, Astrid Ridge |

[30] |

| Columbia River Basalt | Northwestern US | 17–6 | 0.16 | 0.175 | [23][31] | |

| Afro-Arabia | Yemen–Ethiopia | 31–25 | 0.6 | 0.35 | Ethiopia | [31] |

| North Atlantic Igneous Province | Northern Canada, Greenland, the Faeroe Islands, Norway, Ireland, and Scotland | 62–55 | 1.3 | 6.6 | High Arctic Large Igneous Province | [31] |

| Deccan Traps | India southern Pakistan | 66 | 0.5–0.8 | 0.5–1.0 | [31] | |

| Madagascar | 88 | [32] | ||||

| Rajmahal Traps | 116 | [24][25] | ||||

| Ontong-Java Plateau | Pacific Ocean | ~122 | 1.86 | 8.4 | Manihiki Plateau and Hikurangi Plateau | [31] |

| Paraná and Etendeka traps | Brazil–Namibia | 134–129 | 1.5 | >1 | Equatorial Atlantic Magmatic Province | [31] |

| Karoo-Ferrar Province | South Africa, Antarctica, Australia, and New Zealand | 183–180 | 0.15–2 | 0.3 | [31] | |

| Central Atlantic magmatic province | Northern South America, Northwest Africa, Iberia, Eastern North America | 197–199 | 11 | 2.5 (2.0 – 3.0) | [33][34] | |

| Siberian Traps | Russia | 250 | 1.5–3.9 | 0.9–2.0 | [31] | |

| Emeishan Traps | Southwestern China | 253–250 | 0.25 | ~0.3 | [31] | |

| Warakurna large igneous province | Australia | 1078–�1073 | 1.5 | Eastern Pilbara | [35] |

Large rhyolitic provinces (LRPs)

These LIPs are composed dominantly of felsic materials. Examples include:

- Whitsunday

- Sierra Madre Occidental (Mexico)

- Malani

- Chon Aike (Argentina)

- Gawler (Australia)

Large Andesitic Provinces (LAPs)

These LIPs are comprised dominantly of andesitic materials. Examples include:

- Island arcs such as Indonesia & Japan

- Active continental margins such as the Andes and the Cascades

- Continental collision zones such as the Anatolia-Iran zone

- High Arctic Large Igneous Province (includes the Ellesmere Island Volcanics, Strand Fiord Formation, Alpha Ridge, Franz Josef Land and Svalbard.)

- North Atlantic Igneous Province (includes basalts in Greenland, Iceland, Ireland, Scotland, Faroes)

Large basaltic provinces (LBPs)

This subcategory includes most of the provinces included in the original LIP classifications. It is composed of continental flood basalts, oceanic flood basalts, and diffuse provinces.

Continental flood basalts

- Ethiopian Highlands

- Columbia River Basalt Group

- Deccan Traps (India)

- Coppermine River Group (Canadian Shield)

- Equatorial Atlantic Magmatic Province (Maranhão, Brazil-Ghana)

- Midcontinent Rift System, Great Lakes Region, North America

- Paraná and Etendeka traps (Paraná, Brazil–NE Namibia)

- Brazilian Highlands

- Río de la Plata Craton (Uruguay)

- Karoo-Ferrar (South Africa–Antarctica)

- Siberian Traps (Russia)

- Emeishan Traps (western China)

- Central Atlantic Magmatic Province (eastern United States and Canada, northern South America, northwest Africa)

Oceanic flood basalts/ oceanic plateaus

- Wrangellia Terrane (Alaska and Canada)

- Caribbean large igneous province (Caribbean Sea)

- Kerguelen Plateau (Indian Ocean)

- Ontong Java Plateau, Manihiki Plateau and Hikurangi Plateau (southwest Pacific Ocean)

- Jameson Land

Large basaltic–rhyolitic provinces (LBRPs)

- Snake River Plain – Oregon High Lava Plains

- Dongargarh (Ethiopia)

Large plutonic provinces (LPP)

Large granitic provinces (LGP)

- Patagonia

- Peru–Chile Batholith

- Coast Range Batholith (NW US)

Other large plutonic provinces

- parts of Central Atlantic Magmatic Province (eastern United States and Canada, northern South America, northwest Africa)

Related structures

Volcanic rifted margins

Extension thins the crust. Magma reaches the surface through radiating sills and dikes, forming basalt flows, as well as deep and shallow magma chambers below the surface. The crust gradually thins due to thermal subsidence, and originally horizontal basalt flows are rotated to become seaward dipping reflectors.

Volcanic rifted margins are found on the boundary of large igneous provinces. Volcanic margins form when rifting is accompanied by significant mantle melting, with volcanism occurring before and/or during continental breakup. Volcanic rifted margins are characterized by: a transitional crust composed of basaltic igneous rocks, including lava flows, sills, dikes, and gabbros, high volume basalt flows, seaward-dipping reflector sequences (SDRS) of basalt flows that were rotated during the early stages of breakup, limited passive-margin subsidence during and after breakup, and the presence of a lower crust with anomalously high seismic P-wave velocities in lower crustal bodies (LCBs), indicative of lower temperature, dense media.

Example of volcanic margins include:

- The Yemen margin

- The East Australian margin

- The West Indian margin

- The Hatton–Rockal margin

- The US East Coast

- The mid-Norwegian margin

- The Brazilian margins

- The Namibian margin

Dike swarms

A dike swarm is a large geological structure consisting of a major group of parallel, linear, or radially oriented dikes intruded within continental crust. They consist of several to hundreds of dikes emplaced more or less contemporaneously during a single intrusive event and are magmatic and stratigraphic. Such dike swarms are the roots of a volcanic province. Examples include:

- Mackenzie dike swarm (Canadian Shield)

- Long Range dikes (Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada)

- Mistassini dike swarm (western Quebec, Canada)

- Matachewan dike swarm (northern Ontario, Canada)

- Sorachi Plateau and Belt (Hokkaido, Japan)

Sills

A series of related sills that were formed essentially contemporaneously (with several million years) from related dikes comprise an LIP if their area is sufficiently large. Examples include:

- Winagami sill complex (northwestern Alberta, Canada)

- Bushveld Igneous Complex (South Africa) with at area of over 66,000 km2 (25,000 sq mi), and a thickness reaching 9 kilometres (5.6 mi) thick.

See also

- Igneous rock

- Geologic province

- Hotspots

- Lithosphere

- Oceanic plateau

- Orogeny

- Peridotite

- Pluton

- Subduction zone

- Supervolcano

- Volcanic passive margin

References

- ↑ Foulger, G.R. (2010). Plates vs. Plumes: A Geological Controversy. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-6148-0.

- 1 2 3 Sheth, Hetu C. (2007). "'Large Igneous Provinces (LIPs)': Definition, recommended terminology, and a hierarchical classification" (PDF). Earth-Science Reviews 85 (3–4): 117–124. Bibcode:2007ESRv...85..117S. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2007.07.005.

- ↑ Michael R. Rampino & Richard B. Stothers (1988). "Flood Basalt Volcanism During the Past 250 Million Years" (PDF). Science 241 (4866): 663–668. doi:10.1126/science.241.4866.663. PMID 17839077.

- ↑ David P.G. Bond & Paul B. Wignall (2014). "Large igneous provinces and mass extinctions: An update". GSA Special Papers: 590. doi:10.1130/2014.2505(02).

- ↑ Coffin, M; Eldholm, O (1992). "Volcanism and continental break-up: a global compilation of large igneous provinces". In Storey, B.C., Alabaster, T., Pankhurst, R.J. Magmatism and the Causes of Continental Breakup. Special Publications 68. London: Geological Society of London. pp. 17–30. Bibcode:1992GSLSP..68...17C. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.1992.068.01.02.

- 1 2 3 Bryan, Scott; Ernst, Richard (2007). "Proposed Revision to Large Igneous Province Classification". doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2007.08.008.

- ↑ N. I. Eremin; Platform Magmatism: Geology and Minerageny; ISSN 1075-7015, Geology of Ore Deposits, 2010, Vol. 52, No. 1, pp. 77–80. © Pleiades Publishing, Ltd., 2010. doi:10.1134/S1075701510010071

- ↑ M.-F. Zhou et al.; Two magma series and associated ore deposit types in the Permian Emeishan large igneous province, SW China; Lithos; Vol. 103 (2008) pp.352–368; doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2007.10.006

- 1 2 Braun, J; The many surface expressions of mantle dynamics; Nature Geosciences; VOL 3; DECEMBER 2010; doi:10.1038/ngeo1020

- 1 2 Allen, Philip A (2011). "Geodynamics: Surface impact of mantle processes". Nature Geoscience 4: 498–499. doi:10.1038/ngeo1216.

- 1 2 Humphreys, Eugene; Schmandt, Brandon (2011). "Looking for mantle plumes". Physics Today 64 (8): 34. doi:10.1063/PT.3.1217.

- ↑ Vincent Courtillot, Anne Davaille, Jean Besse, & Joann Stock ;Three distinct types of hotspots in the Earth’s mantle; Earth and Planetary Science Letters; V. 205; 2003; pp.295–308

- ↑ E. Humphreys and B. Schmandt; Looking for Mantle Plumes; Physics Today; August 2011; pp. 34- 39

- 1 2 3 J.T. Hagstrum; Antipodal hotspots and bipolar catastrophes: Were oceanic large-body impacts the cause?; Earth and Planetary Science Letters; Vol 236; (2005) pp. 13–27; doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2005.02.020

- ↑ Matthew G. Jackson & Richard W. Carlson; An ancient recipe for flood-basalt genesis; Nature (2011) doi:10.1038/nature10326

- ↑ Coffin, M.F., Eldholm, O. (Eds.), 1991. Large Igneous Provinces: JOI/USSAC workshop report. The University of Texas at Austin Institute for Geophysics Technical Report, p. 114.

- ↑ Coffin, M.F., Eldholm, O., 1992. Volcanism and continental break-up: a global compilation of large igneous provinces. In: Storey, B.C., Alabaster, T., Pankhurst, R.J. (Eds.), Magmatism and the Causes of Continental Break-up. Geological Society of London Special Publication, vol. 68, pp. 17–30.

- ↑ Coffin, M.F., Eldholm, O., 1994. Large igneous provinces: crustal structure, dimensions, and external consequences. Reviews of Geophysics Vol. 32, pp. 1–36.

- 1 2 3 4 S.E. Bryan & R.E. Ernst; Revised definition of Large Igneous Provinces (LIPs); Earth-Science Reviews Vol. 86 (2008) pp. 175–202

- ↑ Ernst, R. E.; Buchan, K. L., (1997), "Giant Radiating Dyke Swarms: Their Use in Identifying Pre-Mesozoic Large Igneous Provinces and Mantle Plumes", in Mahoney, J. J.; Coffin, M. F. (editors), Large Igneous Provinces: Continental, Oceanic and Flood Volcanism (Geophysical Monograph 100), Washington D.C.: American Geophysical Union, p. 297, ISBN 0-87590-082-8

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 M.A. Richards, R.A. Duncan, V.E. Courtillot; Flood Basalts and Hot-Spot Tracks: Plume Heads and Tails; SCIENCE, VOL. 246 (1989) 103–108

- 1 2 Antretter, M.; Riisager, P.; Hall, S.; Zhao, X.; and Steinberger, B. (2004). Modelled palaeolatitudes for the Louisville hot spot and the Ontong Java Plateau, in Origin and Evolution of the Ontong Java Plateau Geological Society, London, Special Publications, v. 229, p. 21-30. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2004.229.01.03.

- 1 2 Barbara P. Nash, Michael E. Perkins, John N. Christensen, Der-Chuen Lee, & A.N. Halliday; The Yellowstone hotspot in space and time: Nd and Hf isotopes in silicic magmas; Earth and Planetary Science Letters 247 (2006) 143–156

- 1 2 Weis, D.; et al. (1993). "The Influence of Mantle Plumes in Generation of Indian Oceanic Crust". Geophysical Monograph 70: 57–89. Bibcode:1992GMS....70...57W. doi:10.1029/gm070p0057.

- 1 2 E.V. Verzhbitsky; Geothermal regime and genesis of the Ninety-East and Chagos-Laccadive ridges;Journal of Geodynamics; Volume 35, Issue 3, April 2003, Pages 289–302

- ↑ Sur l'âge des trapps basaltiques (On the ages of flood basalt events); Vincent E. Courtillot & Paul R. Renne; Comptes Rendus Geoscience; Vol: 335 Issue: 1, January 2003; pp: 113–140

- ↑ Kaj Hoernle, Folkmar Hauff and Paul van den Bogaard, 70 m.y. history (139–69 Ma) for the Caribbean large igneous province, Geology; August 2004; v. 32; no. 8; p. 697-700 Abstract

- ↑ Ernst, Richard E.; Buchan, Kenneth L. (2001). Mantle plumes: their identification through time. Geological Society of America. pp. 143, 145, 146, 147, 148, 259. ISBN 0-8137-2352-3.

- ↑ Kerr, AC (December 2005). "Oceanic LIPS: Kiss of death". Elements 1 (5): 289–292. doi:10.2113/gselements.1.5.289.

- ↑ Gohl, K.; Uenzelmann-Neben, G.; Grobys, N. (2011). "Growth and dispersal of a southeast African Large Igenous Province" (PDF). South African Journal of Geology 114 (3-4): 379–386. doi:10.2113/gssajg.114.3-4.379. Retrieved April 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 P.S. Ross, I. Ukstins Peateb, M.K. McClintocka, Y.G. Xuc, I.P. Skillingd, J.D.L. Whitea, and B.F. Houghtone; Mafic volcaniclastic deposits in flood basalt provinces: A review; Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 145 (2005) 281–314

- ↑ T.H Torsvik, R.D Tucker, L.D Ashwal, E.A Eide, N.A Rakotosolofo, M.J de Wit; Late Cretaceous magmatism in Madagascar: palaeomagnetic evidence for a stationary Marion hotspot; Earth and Planetary Science Letters, Volume 164, Issues 1–2, 15 December 1998, Pages 221–232

- ↑ Knight, K.B.; Nomade S.; Renne P.R.; Marzoli A.; Bertrand H.; Youbi N. (2004). "The Central Atlantic Magmatic Province at the Triassic–Jurassic boundary: paleomagnetic and 40Ar/39Ar evidence from Morocco for brief, episodic volcanism". Earth and Planetary Science Letters (Elsevier) 228 (1–2): 143–160. Bibcode:2004E&PSL.228..143K. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2004.09.022. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- ↑ Blackburn, Terrence J.; Olsen, Paul E.; Bowring, Samuel A.; McLean, Noah M.; Kent, Dennis V; Puffer, John; McHone, Greg; Rasbury, Troy; Et-Touhami7, Mohammed (2013). "Zircon U–Pb Geochronology Links the End-Triassic Extinction with the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province". Science 340 (6135): 941–945. Bibcode:2013Sci...340..941B. doi:10.1126/science.1234204. PMID 23519213.

- ↑ MTD Wingate, F Pirajno & PA Morris Warakurna large igneous province: A new Mesoproterozoic large igneous province in west-central Australia Geology (2004) Volume 32; pp.105–108 doi:10.1130/G20171.1

Related reading

- Anderson, DL (December 2005). "Large igneous provinces, delamination, and fertile mantle". Elements 1 (5): 271–275. doi:10.2113/gselements.1.5.271.

- Baragar, WRA; Ernst, R.E.; Hulbert, L.; Peterson, T. (1996). "Longitudinal petrochemical variation in the Mackenzie dyke swarm, northwestern Canadian Shield". J. Petrol. 37 (2): 317–359. doi:10.1093/petrology/37.2.317.

- Campbell, IH (December 2005). "Large igneous provinces and the plume hypothesis". Elements 1 (5): 265–269. doi:10.2113/gselements.1.5.265.

- Cohen, B.; Vasconcelos, P.M.D.; Knesel, K. M. (2004). "17th Australian Geological Convention, 8–13 February 2004, held in Hobart, Tasmania". Dynamic Earth: Past, Present and Future (Geological Society of Australia): 256–256.

|chapter=ignored (help) - Ernst, R.E.; Buchan, K.L.; Campbell, I.H. (February 2005). A. Kerr, R. England, and P. Wignall, eds. "Mantle Plumes: Physical Processes, Chemical Signatures, Biological Effects". Lithos 79 (3–4): 271–297. Bibcode:2005Litho..79..271E. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2004.09.004.

|chapter=ignored (help) - "Large Igneous Provinces Commission: Large Igneous Provinces Record". International Association of Volcanology and Chemistry of the Earth's Interior.

- Jones, AP (December 2005). "Meteor impacts as triggers to large igneous provinces". Elements 1 (5): 277–281. doi:10.2113/gselements.1.5.277.

- Marsh, JS; Hooper, PR; Rehacek, J; Duncan, RA; Duncan, AR (1997). "Stratigraphy and age of Karoo basalts of Lesotho and implications for correlations within the Karoo igneous province". In Mahoney JJ and Coffin MF. Large Igneous Provinces: continental, oceanic, and planetary flood volcanism. Geophysical Monograph 100. Washington, DC: American Geophysical Union. pp. 247–272. ISBN 0-87590-082-8.

- Peate, DW (1997). Mahoney JJ and Coffin MF, eds. "Large Igneous Provinces: continental, oceanic, and planetary flood volcanism". Geophysical Monograph 100. Washington, DC: American Geophysical Union: 247–272. ISBN 0-87590-082-8.

|chapter=ignored (help) - Ratajeski, K. (25 November 2005). "The Cretaceous Superplume".

- Ritsema, J.; van Heijst, H.J.; Woodhouse, J.H. (1999). "Complex shear wave velocity structure imaged beneath Africa and Iceland". Science 286 (5446): 1925–1928. doi:10.1126/science.286.5446.1925. PMID 10583949.

- Saunders, AD (December 2005). "Large igneous provinces: origin and environmental consequences". Elements 1 (5): 259–263. doi:10.2113/gselements.1.5.259.

- Segev, A (2002). "Flood basalts, continental breakup and the dispersal of Gondwana: evidence for periodic migration of upwelling mantle flows (plumes)" (PDF). EGU Stephan Mueller Special Publication Series 2: 171–191. doi:10.5194/smsps-2-171-2002. Retrieved 5 August 2010.

- Wignall, P (December 2005). "The link between large igneous provinces eruptions and mass extinctions". Elements 1 (5): 293–297. doi:10.2113/gselements.1.5.293.