Langmuir–Blodgett film

A Langmuir–Blodgett film contains one or more monolayers of an organic material, deposited from the surface of a liquid onto a solid by immersing (or emersing) the solid substrate into (or from) the liquid. A monolayer is adsorbed homogeneously with each immersion or emersion step, thus films with very accurate thickness can be formed. This thickness is accurate because the thickness of each monolayer is known and can therefore be added to find the total thickness of a Langmuir–Blodgett film. The monolayers are assembled vertically and are usually composed of amphiphilic molecules (see Chemical polarity) with a hydrophilic head and a hydrophobic tail (example: fatty acids). Langmuir–Blodgett films are named after Irving Langmuir and Katharine B. Blodgett, who invented this technique while working in Research and Development for General Electric Co. An alternative technique of creating single monolayers on surfaces is that of self-assembled monolayers.

Langmuir–Blodgett films should not be confused with Langmuir films, which tends to describe an organic monolayer submersed in an aqueous solution.

Historical background

Advances to the discovery of Langmuir–Blodgett films began with Benjamin Franklin in 1773 when he dropped about a teaspoon of oil onto a pond. Franklin noticed that the waves were calmed almost instantly and that the calming of the waves spread for about half an acre. What Franklin did not realize was that the oil had formed a monolayer on top of the pond surface. Over a century later, Lord Rayleigh quantified what Benjamin Franklin had seen. Knowing that the oil, oleic acid, had spread evenly over the water, Rayleigh calculated that the thickness of the film was 1.6 nm by knowing the volume of oil dropped and the area of coverage. In addition, he used these calculations to prove the existence of the Avogadro number.

With the help of her kitchen sink, Agnes Pockels showed that area of films can be controlled with barriers. She added that surface tension varies with contamination of water. She used different oils to deduce that surface pressure would not change until area was confined to about 0.2 nm2. This work was originally written as a letter to Lord Rayleigh who then helped Agnes Pockels become published in the journal, Nature, in 1891.

Agnes Pockels’ work set the stage for Irving Langmuir who continued to work and confirmed Pockels’ results. Using Pockels’ idea, he developed the Langmuir (or Langmuir–Blodgett) trough. His observations indicated that chain length did not impact the affected area since the organic molecules were arranged vertically.

Langmuir’s breakthrough did not occur until he hired Katherine Blodgett as his assistant. Blodgett initially went to seek for a job at General Electric (GE) with Langmuir during her Christmas break of her senior year at Bryn Mawr College, where she received a BA in Physics. Langmuir advised to Blodgett that she should continue her education before working for him. She thereafter attended University of Chicago for her MA in Chemistry. Upon her completion of her Master's, Langmuir hired her as his assistant. However, breakthroughs in surface chemistry happened after she received her PhD degree in 1926 from Cambridge University.

While working for GE, Langmuir and Blodgett discovered that when a solid surface is inserted into an aqueous solution containing organic moities, the organic molecules will deposit a monolayer homogeneously over the surface. This is the Langmuir–Blodgett film deposition process. Through this work in surface chemistry and with the help of Blodgett, Langmuir was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1932. In addition, Blodgett used Langmuir–Blodgett film to create 99% transparent anti-reflective glass by coating glass with fluorinated organic compounds, forming a simple anti-reflective coating.

Physical insight

LB films are formed when amphiphilic molecules like surfactants interact with air at an air–water interface. Surfactants (or surface-acting agents) are molecules with hydrophobic 'tails' and hydrophilic 'heads'. When surfactant concentration is less than critical micellar concentration (CMC), the surfactant molecules arrange themselves as shown in Figure 1 below. This tendency can be explained by surface-energy considerations. Since the tails are hydrophobic, their exposure to air is favoured over that to water. Similarly, since the heads are hydrophilic, the head–water interaction is more favourable than air–water interaction. The overall effect is reduction in the surface energy (or equivalently, surface tension of water).

Figure 1: Surfactant molecules arranged on an air–water interface

For very small concentrations, far less than critical micellar concentration (CMC), the surfactant molecules execute a random motion on the water–air interface. This motion can be thought to be similar to the motion of ideal-gas molecules enclosed in a container. The corresponding thermodynamic variables for the surfactant system are, surface pressure ( ), surface area (A) and number of surfactant molecules (N). This system behaves similar to a gas in a container. The density of surfactant molecules as well as the surface pressure increases upon reducing the surface area A ('compression' of the 'gas'). Further compression of the surfactant molecules on the surface shows behavior similar to phase transitions. The ‘gas’ gets compressed into ‘liquid’ and ultimately into a perfectly closed packed array of the surfactant molecules on the surface corresponding to a ‘solid’ state. Instruments like the Langmuir–Blodgett trough can be used to quantify such phenomena.

), surface area (A) and number of surfactant molecules (N). This system behaves similar to a gas in a container. The density of surfactant molecules as well as the surface pressure increases upon reducing the surface area A ('compression' of the 'gas'). Further compression of the surfactant molecules on the surface shows behavior similar to phase transitions. The ‘gas’ gets compressed into ‘liquid’ and ultimately into a perfectly closed packed array of the surfactant molecules on the surface corresponding to a ‘solid’ state. Instruments like the Langmuir–Blodgett trough can be used to quantify such phenomena.

Pressure–area characteristics

Adding a monolayer to the surface reduces the surface tension, and the surface pressure,  is given by the following equation:

is given by the following equation:

where,  is equal to the surface tension of the water and

is equal to the surface tension of the water and  is the surface tension due to the monolayer. But the concentration-dependence of surface tension (similar to Langmuir isotherm) is as follows:

is the surface tension due to the monolayer. But the concentration-dependence of surface tension (similar to Langmuir isotherm) is as follows:

= RTKHC = – RT

= RTKHC = – RT

Thus,

or,

or,

The last equation indicates a relationship similar to ideal gas law. However, it should be noted that the concentration-dependence of surface tension is valid only when the solutions are dilute and concentrations are low. Hence, at very low concentrations of the surfactant, the molecules behave like ideal gas molecules.

Experimentally, the surface pressure is usually measured using the Wilhelmy plate. A pressure sensor/electrobalance arrangement detects the pressure exerted by the monolayer. Also monitored is the area to the side of the barrier which the monolayer resides.

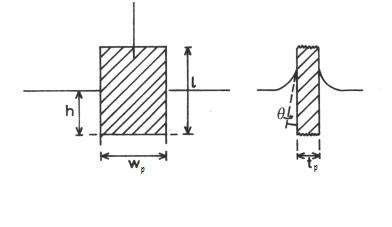

Figure 2. A Wilhelmy plate

A simple force balance on the plate leads to the following equation for the surface pressure:

![\Pi = -\Delta \gamma = - \left[ \frac{\Delta F}{2(t_{p} + w_{p})} \right] \approx - \frac{\Delta F}{2w_{p}}](../I/m/f7281196e784cd005a32e60aac586d4a.png) ,

,

only when  .

.

Here,  and

and  are the dimensions of the plate, and

are the dimensions of the plate, and  is the difference in forces. The Wilhelmy plate measurements give pressure – area isotherms that show phase transition-like behaviour of the LB films, as mentioned before (see figure below). In the gaseous phase, there is minimal pressure increase for a decrease in area. This continues until the first transition occurs and there is a proportional increase in pressure with decreasing area. Moving into the solid region is accompanied by another sharp transition to a more severe area dependent pressure. This trend continues up to a point where the molecules are relatively close packed and have very little room to move. Applying an increasing pressure at this point causes the monolayer to become unstable and destroy the monolayer.

is the difference in forces. The Wilhelmy plate measurements give pressure – area isotherms that show phase transition-like behaviour of the LB films, as mentioned before (see figure below). In the gaseous phase, there is minimal pressure increase for a decrease in area. This continues until the first transition occurs and there is a proportional increase in pressure with decreasing area. Moving into the solid region is accompanied by another sharp transition to a more severe area dependent pressure. This trend continues up to a point where the molecules are relatively close packed and have very little room to move. Applying an increasing pressure at this point causes the monolayer to become unstable and destroy the monolayer.

Figure 3. (i) Surface pressure – Area isotherms. (ii) Molecular configuration in the three regions marked in the

-A curve; (a) gaseous phase, (b) liquid-expanded phase, and (c) condensed phase. (Adapted from Osvaldo N. Oliveira Jr., Brazilian Journal of Physics, vol. 22, no. 2, June 1992)

-A curve; (a) gaseous phase, (b) liquid-expanded phase, and (c) condensed phase. (Adapted from Osvaldo N. Oliveira Jr., Brazilian Journal of Physics, vol. 22, no. 2, June 1992)Applications

Many possible applications have been suggested over years for Langmuir–Blodgett films. Their characteristics are extremely thin films and high degree of structural order. These films have different optical, electrical and biological properties which are composed of some specific organic compounds. Organic compounds usually have more positive responses than inorganic materials for outside factors (pressure, temperature or gas change).

- LB films can be used as passive layers in MIS (metal-insulator-semiconductor) which have more open structure than silicon oxide, and they allow gases to penetrate to the interface more effectively.

- LB films also can be used as biological membranes. Lipid molecules with the fatty acid moiety of long carbon chains attached to a polar group have received extended attention because of being naturally suited to the Langmuir method of film production. This type of biological membrane can be used to investigate: the modes of drug action, the permeability of biologically active molecules, and the chain reactions of biological systems.

- Also, it is possible to propose field effect devices for observing the immunological response and enzyme-substrate reactions by collecting biological molecules such as antibodies and enzymes in insulating LB films.

- Anti-reflective glass can be produced with successive layers of fluorinated organic film.

- The glucose biosensor can be made of poly(3-hexyl thiopene) as Langmuir–Blodgett film, which entraps glucose-oxide and transfers it to a coated indium-tin-oxide glass plate.

- UV resists can be made of poly(N-alkylmethacrylamides) Langmuir–Blodgett film.

- UV light and conductivity of a Langmuir–Blodgett film.

- Langmuir–Blodgett films are inherently 2D-structures and can be built up layer by layer, by dipping hydrophobic or hydrophilic substrates into a liquid sub-phase.

- Langmuir–Blodgett patterning is a new paradigm for large-area patterning with mesostructured features[1][2]

See also

References

- ↑ Chen, Xiaodong; Lenhert, Steven; Hirtz, Michael; Lu, Nan; Fuchs, Harald; Chi, Lifeng (2007). "Langmuir–Blodgett Patterning: A Bottom–Up Way to Build Mesostructures over Large Areas". Accounts of Chemical Research 40 (6): 393–401. doi:10.1021/ar600019r. PMID 17441679.

- ↑ Purrucker, Oliver; Förtig, Anton; Lüdtke, Karin; Jordan, Rainer; Tanaka, Motomu (2005). "Confinement of Transmembrane Cell Receptors in Tunable Stripe Micropatterns". Journal of the American Chemical Society 127 (4): 1258–64. doi:10.1021/ja045713m. PMID 15669865.

Bibliography

- R. W. Corkery, Langmuir, 1997, 13 (14), 3591–3594

- Osvaldo N. Oliveira Jr., Brazilian Journal of Physics, vol. 22, no. 2, June 1992

- Roberts G G, Pande K P and Barlow, Phys. Technol., Vol. 12, 1981

- Singhal, Rahul. Poly-3-Hexyl Thiopene Langmuir-Blodgett Films for Application to Glucose Biosensor. National Physics Laboratory: Biotechnology and Bioengineering, p 277-282, February 5, 2004. John and Wiley Sons Inc.

- Guo, Yinzhong. Preparation of poly(N-alkylmethacrylamide) Langmuir–Blodgett films for the application to a novel dry-developed positive deep UV resist. Macromolecules, p1115-1118, February 23, 1999. ACS

- Franklin, Benjamin, Of the stilling of Waves by means of Oil. Letter to William Brownrigg and the Reverend Mr. Farish. London, November 7, 1773.

- Pockels, A., Surface Tension, Nature, 1891, 43, 437.

- Blodgett, Katherine B., Use of Interface to Extinguish Reflection of Light from Glass. Physical Review, 1939, 55,

- A. Ulman, An Introduction to Ultrathin Organic Films From Langmuir-Blodgett to Self-Assembly, Academic Press, Inc.: San Diego (1991).

- I.R. Peterson, "Langmuir Blodgett Films ", J. Phys. D 23, 4, (1990) 379–95.

- I.R. Peterson, "Langmuir Monolayers", in T.H. Richardson, Ed., Functional Organic and Polymeric Materials Wiley: NY (2000).

- L.S. Miller, D.E. Hookes, P.J. Travers and A.P. Murphy, "A New Type of Langmuir-Blodgett Trough", J. Phys. E 21 (1988) 163–167.

- I.R.Peterson, J.D.Earls. I.R.Girling and G.J.Russell, "Disclinations and Annealing in Fatty-Acid Monolayers", Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 147 (1987) 141–147.

- A.M.Bibo, C.M.Knobler and I.R.Peterson, "A Monolayer Phase Miscibility Comparison of the Long Chain Fatty Acids and Their Ethyl Esters", J. Phys. Chem. 95 (1991) 5591–5599.

External links

- http://www.apexicindia.com

- http://www.kibron.com

- http://www.ksvinc.com/LB.htm

- http://www.nima.co.uk

- http://www.edisonexploratorium.org/bio/blodgett.htm

- http://www.aist.go.jp/NIMC/overview/v2.html

- KSV Instruments LTD. Helsinki, Finland. http://www.ksvltd.fi/Literature/Application%20notes/LB.pdf

- http://home.frognet.net/~ejcov/blodgett2.html

- Sarfus images of Langmuir–Blodgett films: http://www.nano-lane.com/langmuir-blodgett.php