Landau theory

Landau theory in physics is a theory that Lev Landau introduced in an attempt to formulate a general theory of continuous (i.e., second-order) phase transitions.[1]

Mean-field formulation (no long-range correlation)

Landau was motivated to suggest that the free energy of any system should obey two conditions:

- It is analytic.

- It obeys the symmetry of the Hamiltonian.

Given these two conditions, one can write down (in the vicinity of the critical temperature, Tc) a phenomenological expression for the free energy as a Taylor expansion in the order parameter.

Ising Model Example

For example, the Ising model free energy in the vicinity of the phase transition may be written as the following, where the variable  is the coarse-grained field of spins, known as the order parameter or the total magnetization.

is the coarse-grained field of spins, known as the order parameter or the total magnetization.

We can truncate the free energy to the 4th power in  without losing the physics of the phase transition, but in general, there are higher order terms present.

For the system to be thermodynamically stable, the parameter on the highest even power of the order parameter must be positive. In this case, we find that

without losing the physics of the phase transition, but in general, there are higher order terms present.

For the system to be thermodynamically stable, the parameter on the highest even power of the order parameter must be positive. In this case, we find that  , such that the free energy is bound.

, such that the free energy is bound.

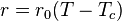

The phase transition occurs at some critical temperature  . Noticing that the minimum in the free energy changes from

. Noticing that the minimum in the free energy changes from  to

to  when the parameter

when the parameter  changes sign, we can write the parameter

changes sign, we can write the parameter  as a function of temperature as such:

as a function of temperature as such:

where  is some temperature independent constant.

The constant

is some temperature independent constant.

The constant  can be safely taken to be zero because it is simply a constant shift in the free energy, which has no effect on the physics of the phase transition.

can be safely taken to be zero because it is simply a constant shift in the free energy, which has no effect on the physics of the phase transition.

The Ising model theory of Landau first raised the order parameter to prominence. Note that the Ising model exhibits the following discrete symmetry: If every spin in the model is flipped, such that  , where

, where  is the value of the

is the value of the  spin, the Hamiltonian (and consequently the free energy) remains unchanged for zero external field

spin, the Hamiltonian (and consequently the free energy) remains unchanged for zero external field  . This symmetry is reflected in the even powers of

. This symmetry is reflected in the even powers of  in

in  .

.

Applications

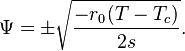

Landau theory has been extraordinarily useful. While the exact values of the parameters  and

and  were unknown, critical exponents could still be calculated with ease, and only depend on the original assumptions of symmetry and analyticity. For the Ising model case, the equilibrium magnetization

were unknown, critical exponents could still be calculated with ease, and only depend on the original assumptions of symmetry and analyticity. For the Ising model case, the equilibrium magnetization  assumes the following value below the critical temperature

assumes the following value below the critical temperature  :

:

At the time, it was known experimentally that the liquid–gas coexistence curve and the ferromagnet magnetization curve both exhibited a scaling relation of the form  , where

, where  was mysteriously the same for both systems. This is the phenomenon of universality. It was also known that simple liquid–gas models are exactly mappable to simple magnetic models, which implied that the two systems possess the same symmetries. It then followed from Landau theory why these two apparently disparate systems should have the same critical exponents, despite having different microscopic parameters. It is now known that the phenomenon of universality arises for other reasons (see Renormalization group). In fact, Landau theory predicts the incorrect critical exponents for the Ising and liquid–gas systems.

was mysteriously the same for both systems. This is the phenomenon of universality. It was also known that simple liquid–gas models are exactly mappable to simple magnetic models, which implied that the two systems possess the same symmetries. It then followed from Landau theory why these two apparently disparate systems should have the same critical exponents, despite having different microscopic parameters. It is now known that the phenomenon of universality arises for other reasons (see Renormalization group). In fact, Landau theory predicts the incorrect critical exponents for the Ising and liquid–gas systems.

The great virtue of Landau theory is that it makes specific predictions for what kind of non-analytic behavior one should see when the underlying free energy is analytic. Then, all the non-analyticity at the critical point, the critical exponents, are because the equilibrium value of the order parameter changes non-analytically, as a square root, whenever the free energy loses its unique minimum.

The extension of Landau theory to include fluctuations in the order parameter shows that Landau theory is only strictly valid near the critical points of ordinary systems with spatial dimensions of higher than 4. This is the upper critical dimension, and it can be much higher than four in more finely tuned phase transition. In Mukhamel's analysis of the isotropic Lifschitz point, the critical dimension is 8. This is because Landau theory is a mean field theory, and does not include long-range correlations.

This theory does not explain non-analyticity at the critical point, but when applied to superfluid and superconductor phase transition, Landau's theory provided inspiration for another theory, the Ginzburg–Landau theory of superconductivity.

Including long-range correlations

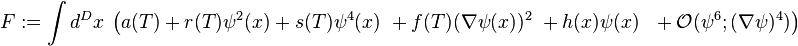

Consider the Ising model free energy above. Assume that the order parameter  and external magnetic field,

and external magnetic field,  , may have spatial variations. Now, the free energy of the system can be assumed to take the following modified form:

, may have spatial variations. Now, the free energy of the system can be assumed to take the following modified form:

where  is the total spatial dimensionality. So,

is the total spatial dimensionality. So,

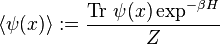

Assume that, for a localized external magnetic perturbation  , the order parameter takes the form

, the order parameter takes the form  . Then,

. Then,

That is, the fluctuation  in the order parameter corresponds to the order-order correlation. Hence, neglecting this fluctuation (like in the earlier mean-field approach) corresponds to neglecting the order-order correlation, which diverges near the critical point.

in the order parameter corresponds to the order-order correlation. Hence, neglecting this fluctuation (like in the earlier mean-field approach) corresponds to neglecting the order-order correlation, which diverges near the critical point.

One can also solve [2] for  , from which the scaling exponent,

, from which the scaling exponent,  , for correlation length

, for correlation length  can deduced. From these, the Ginzburg criterion for the upper critical dimension for the validity of the Ising mean-field Landau theory (the one without long-range correlation) can be calculated as:

can deduced. From these, the Ginzburg criterion for the upper critical dimension for the validity of the Ising mean-field Landau theory (the one without long-range correlation) can be calculated as:

In our current Ising model, mean-field Landau theory gives  and so, it (the Ising mean-field Landau theory) is valid only for spatial dimensionality greater than or equal to 4 (at the marginal values of

and so, it (the Ising mean-field Landau theory) is valid only for spatial dimensionality greater than or equal to 4 (at the marginal values of  , there are small corrections to the exponents). This modified version of mean-field Landau theory is sometimes also referred to as the Landau-Ginzburg theory of Ising phase transitions. As a clarification, there is also a Landau-Ginzburg theory specific to superconductivity phase transition, which also includes fluctuations.

, there are small corrections to the exponents). This modified version of mean-field Landau theory is sometimes also referred to as the Landau-Ginzburg theory of Ising phase transitions. As a clarification, there is also a Landau-Ginzburg theory specific to superconductivity phase transition, which also includes fluctuations.

See also

Further reading

- Landau L.D. Collected Papers (Nauka, Moscow, 1969)

- Michael C. Cross, Landau theory of second order phase transitions, (Caltech statistical mechanics lecture notes).

- Yukhnovskii, I R, Phase Transitions of the Second Order – Collective Variables Method, World Scientific, 1987, ISBN 9971-5-0087-6

Footnotes

- ↑ Landau L.D., Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz. 7, pp. 19–32 (1937)

- ↑ "Equilibrium Statistical Physics" by Michael Plischke, Birger Bergersen, Section 3.10, 3rd ed