Landau quantization

Landau quantization in quantum mechanics is the quantization of the cyclotron orbits of charged particles in magnetic fields. As a result, the charged particles can only occupy orbits with discrete energy values, called Landau levels. The Landau levels are degenerate, with the number of electrons per level directly proportional to the strength of the applied magnetic field. Landau quantization is directly responsible for oscillations in electronic properties of materials as a function of the applied magnetic field. It is named after the Soviet physicist Lev Landau.

Derivation

Consider a two-dimensional system of non-interacting particles with charge q and spin S confined to an area A = LxLy in the x-y plane.

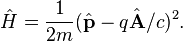

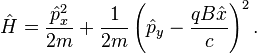

Apply a uniform magnetic field  along the z-axis. In CGS units, the Hamiltonian of this system is

along the z-axis. In CGS units, the Hamiltonian of this system is

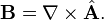

Here, p̂ is the canonical momentum operator and  is the electromagnetic vector potential, which is related to the magnetic field by

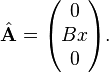

There is some gauge freedom in the choice of vector potential for a given magnetic field. The Hamiltonian is gauge invariant, which means that adding the gradient of a scalar field to  changes the overall phase of the wave function by an amount corresponding to the scalar field. But physical properties are not influenced by the specific choice of gauge. For simplicity in calculation, choose the Landau gauge, which is

where B=|B| and x̂ is the x component of the position operator.

In this gauge, the Hamiltonian is

The operator  commutes with this Hamiltonian, since the operator ŷ is absent by the choice of gauge. Thus the operator

commutes with this Hamiltonian, since the operator ŷ is absent by the choice of gauge. Thus the operator  can be replaced by its eigenvalue ħky .

can be replaced by its eigenvalue ħky .

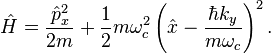

The Hamiltonian can also be written more simply by noting that the cyclotron frequency is ωc = qB/mc, giving

This is exactly the Hamiltonian for the quantum harmonic oscillator, except with the minimum of the potential shifted in coordinate space by x0 = ħky/mωc .

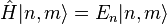

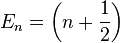

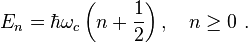

To find the energies, note that translating the harmonic oscillator potential does not affect the energies. The energies of this system are thus identical to those of the standard quantum harmonic oscillator,

The energy does not depend on the quantum number ky, so there will be degeneracies.

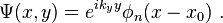

For the wave functions, recall that  commutes with the Hamiltonian. Then the wave function factors into a product of momentum eigenstates in the y direction and harmonic oscillator eigenstates

commutes with the Hamiltonian. Then the wave function factors into a product of momentum eigenstates in the y direction and harmonic oscillator eigenstates  shifted by an amount x0 in the x direction:

shifted by an amount x0 in the x direction:

In sum, the state of the electron is characterized by two quantum numbers, n and ky .

Landau levels

Each set of wave functions with the same value of n is called a Landau level. Effects of Landau levels are only observed when the mean thermal energy is smaller than the energy level separation, kT ≪ ħωc, meaning low temperatures and strong magnetic fields.

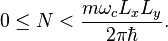

Each Landau level is degenerate because of the second quantum number ky, which can take the values

,

,

where N is an integer. The allowed values of N are further restricted by the condition that the center of force of the oscillator, x0, must physically lie within the system, 0 ≤ x0 < Lx. This gives the following range for N,

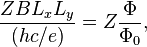

For particles with charge q = Ze, the upper bound on N can be simply written as a ratio of fluxes,

where Φ0 = h/2e is the fundamental quantum of flux and Φ = BA is the flux through the system (with area A = LxLy).

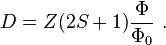

Thus, for particles with spin S, the maximum number D of particles per Landau level is

The above gives only a rough idea of the effects of finite-size geometry. Strictly speaking, using the standard solution of the harmonic oscillator is only valid for systems unbounded in the x-direction (infinite strips). If the size Lx is finite, boundary conditions in that direction give rise to non-standard quantization conditions on the magnetic field, involving (in principle) both solutions to the Hermite equation. The filling of these levels with many electrons is still[1] an active area of research.

In general, Landau levels are observed in electronic systems, where Z=1 and S=1/2. As the magnetic field is increased, more and more electrons can fit into a given Landau level. The occupation of the highest Landau level ranges from completely full to entirely empty, leading to oscillations in various electronic properties (see de Haas–van Alphen effect and Shubnikov–de Haas effect).

If Zeeman splitting is included, each Landau level splits into a pair, one for spin up electrons and the other for spin down electrons. Then the occupation of each spin Landau level is just the ratio of fluxes D = Φ/Φ0. Zeeman splitting has a significant effect on the Landau levels because their energy scales are the same, 2μBB = ħω . However, the Fermi energy and ground state energy stay roughly the same in a system with many filled levels, since pairs of split energy levels cancel each other out when summed.

Discussion

This derivation treats x and y as slightly asymmetric. However, by the symmetry of the system, there is no physical quantity which distinguishes these coordinates. The same result could have been obtained with an appropriate interchange of x and y.

Moreover, the above derivation assumed an electron confined in the z-direction, which is a relevant experimental situation — found in two-dimensional electron gases, for instance. Still, this assumption is not essential for the results. If electrons are free to move along the z direction, the wave function acquires an additional multiplicative term exp(ikzz); the energy corresponding to this free motion, (ħ kz)2/(2m), is added to the E discussed. This term then fills in the separation in energy of the different Landau levels, blurring the effect of the quantization. Nevertheless, the motion in the x-y-plane, perpendicular to the magnetic field, is still quantized.

Landau Levels in Symmetric Gauge

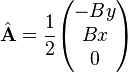

The symmetric gauge refers to the choice

In terms of dimensionless lengths and energies, the Hamiltonian can be expressed as

The correct units can be restored by introducing factors of  and

and

Consider operators

These operators follow certain commutation relations

![[\hat{a}, \hat{a}^{\dagger}] = [\hat{b},\hat{b}^{\dagger}] = 1](../I/m/ad83e9531f9565832418fac54af61027.png) .

.

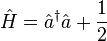

In terms of above operators the Hamiltonian can be written as

Landau Level index  is the eigenvalue of

is the eigenvalue of

The z component of angular momentum is

Exploiting the property ![[\hat{H}, \hat{L}_z] = 0](../I/m/1a2798e54d5c6e09bbd41872a96d0b71.png) we chose eigenfunctions which diagonalize

we chose eigenfunctions which diagonalize  and

and  , The eigenvalue of

, The eigenvalue of  is denoted by

is denoted by  , where it is clear that

, where it is clear that  in the

in the  th Landau level. However, it may be arbitrarily large, which is necessary to obtain the infinite degeneracy (or finite degeneracy per unit area) exhibited by the system.

th Landau level. However, it may be arbitrarily large, which is necessary to obtain the infinite degeneracy (or finite degeneracy per unit area) exhibited by the system.

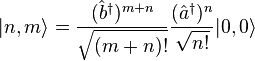

The application of  increases

increases  by one unit while preserving

by one unit while preserving  , whereas

, whereas  application simultaneously increase

application simultaneously increase  and decreases

and decreases  by one unit. The analogy to quantum harmonic oscillator provides solutions

by one unit. The analogy to quantum harmonic oscillator provides solutions

Each Landau level has degenerate orbitals labeled by the quantum numbers ky and  in the Landau and symmetric gauges respectively. The degeneracy per unit area is the same in each Landau level.

in the Landau and symmetric gauges respectively. The degeneracy per unit area is the same in each Landau level.

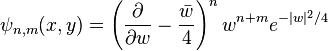

One may verify that the above states correspond to choosing wavefunctions proportional to

where  .

.

In particular, the lowest Landau level  consists of arbitrary analytic functions multiplying a Gaussian,

consists of arbitrary analytic functions multiplying a Gaussian,  .

.

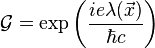

Effects of Gauge Transformation

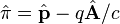

The definition for kinematical momenta is

where  is the canonical momenta. The Hamiltonian is a gauge invariant so

is the canonical momenta. The Hamiltonian is a gauge invariant so  and

and  will remain invariant under gauge transformations but

will remain invariant under gauge transformations but  will depend upon gauge.

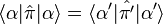

For observing the effect of gauge transformation on the quantum state of the particle, consider the state with A and A' as Vector Potential, with states

will depend upon gauge.

For observing the effect of gauge transformation on the quantum state of the particle, consider the state with A and A' as Vector Potential, with states  and

and  .

.

As  and

and  is invariant under the gauge transformation we get

is invariant under the gauge transformation we get

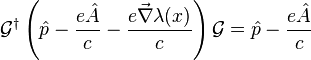

Consider an operator  such that

such that

from above relation we deduce that

from this we conclude

See also

- Barkhausen effect

- de Haas–van Alphen effect

- Shubnikov–de Haas effect

- Quantum Hall effect

- Laughlin wavefunction

- Coulomb potential between two current loops embedded in a magnetic field

Further reading

- Landau, L. D.; and Lifschitz, E. M.; (1977). Quantum Mechanics: Non-relativistic Theory. Course of Theoretical Physics. Vol. 3 (3rd ed. London: Pergamon Press). ISBN 0750635398 .

- ↑ Mikhailov, S. A. (2001). "A new approach to the ground state of quantum Hall systems. Basic principles". Physica B: Condensed Matter 299: 6. doi:10.1016/S0921-4526(00)00769-9.

![\hat{H} = \frac{1}{2} \left[\left(-i\frac{\partial}{\partial x} - \frac{y}{2}\right)^2 + \left(-i \frac{\partial}{\partial y} + \frac{x}{2}\right)^2 \right]](../I/m/390560e7fbf101e29256125086eef73e.png)

![\hat{a} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \left[\left(\frac{x}{2} + \frac{\partial}{\partial x}\right) -i \left(\frac{y}{2} + \frac{\partial}{\partial y}\right)\right]](../I/m/c096f20a246ca31311cbe7376f9f5f79.png)

![\hat{a}^{\dagger} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \left[\left(\frac{x}{2} - \frac{\partial}{\partial x}\right) +i \left(\frac{y}{2} - \frac{\partial}{\partial y}\right)\right]](../I/m/50b0abedce709aef676c68a7d4ee58cb.png)

![\hat{b} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \left[\left(\frac{x}{2} + \frac{\partial}{\partial x}\right) +i \left(\frac{y}{2} + \frac{\partial}{\partial y}\right)\right]](../I/m/e969724350964181c83500f7c5ce1051.png)

![\hat{b}^{\dagger} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \left[\left(\frac{x}{2} - \frac{\partial}{\partial x}\right) -i \left(\frac{y}{2} - \frac{\partial}{\partial y}\right)\right]](../I/m/c098e057528850fa5947dcf2b3f75389.png)