Lancaster House

| Lancaster House | |

|---|---|

| |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Neo-classical |

| Location | St James's, London, SW1A 1BB, United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 51°30′14″N 0°8′21″W / 51.50389°N 0.13917°WCoordinates: 51°30′14″N 0°8′21″W / 51.50389°N 0.13917°W |

| Current tenants | Foreign and Commonwealth Office |

| Construction started | 1825 |

| Completed | 1840 |

| Owner | HM Government |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | Three (plus basement) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect |

Benjamin Dean Wyatt (interior and exterior) Sir Charles Barry (interior) Sir Robert Smirke (interior) |

Lancaster House (previously known as York House and Stafford House) is a mansion in the St James's district in the West End of London. It is close to St. James's Palace and much of the site was once part of the palace complex. This Grade I listed building[1][2] is now managed by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office.

History

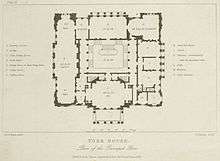

Construction of the house commenced in 1825 for the Duke of York and Albany, the second son of King George III, and it was initially known as York House.[3]:155 Sir Robert Smirke was originally hired to design the house, until under the influence of the Duke's mistress the Duchess of Rutland, he was replaced by Benjamin Dean Wyatt who mainly designed the exterior.[3]:155 The house was only a shell by the time of the death of the Duke in 1827. It is constructed from Bath stone, in a neo-classical style, being the last great London mansion to use this essentially Georgian style.

The house was purchased by and completed for the 2nd Marquess of Stafford (later 1st Duke of Sutherland) and was known as Stafford House for almost a century. It was assessed for rating purposes (i.e. for property taxes) as the most valuable private house in London.

The completed building was three floors in height, the State rooms being on the first floor or piano nobile, family living rooms on the ground floor and family bedrooms on the second floor. There is also a basement containing service rooms, including the government wine cellar.[4] The interior was designed by Benjamin Dean Wyatt, Sir Charles Barry and Sir Robert Smirke and was completed in 1840.

The Sutherlands’ liberal politics and love of the arts attracted many distinguished guests, including factory reformer the Earl of Shaftesbury, anti-slavery author Harriet Beecher Stowe and Italian revolutionary leader Giuseppe Garibaldi. Chopin gave a recital there in 1848 in the presence of Queen Victoria.[5] Almost as influential as the visitors was the décor, which was to set the fashion for London reception rooms for nearly a century. The mainly Louis XIV Style interiors created a stunning backdrop for the Sutherlands’ impressive collection of paintings and objets d’art, much of which can still be seen in the house today.

Queen Victoria is said to have remarked to the Duchess of Sutherland on arriving at Stafford House, "I have come from my House to your Palace." With its ornate decoration and the dramatic sweep of the great staircase, the Grand Hall is a magnificent introduction to one of the finest town houses in London. More than a century later, its grandeur remains and the house is as popular as ever with those who visit it.

In 1912 it was purchased by the Lancastrian soap-maker Sir William Lever, 1st Baronet (later 1st Viscount Leverhulme) who renamed it in honour of his native county of Lancashire and presented it to the nation in the following year.[3]:158-161

From 1924 until shortly after World War II, the house was the home of the London Museum, but it is now used for government receptions and is closed to the public except on rare open days.

The European Advisory Commission met at the house in 1944. In January 1947 a special envoy meeting on affairs concerning occupied Austria was hosted here. The year 1956 saw the signing of the agreement of independence for Malaya. In 1961, South Africa affirmed its intention to become a republic, inside the Commonwealth. In 1979 it was the scene of the Lancaster House Agreement, which was the agreement of independence from the United Kingdom of Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe.[3]:161

The house was the venue for the 10th G7 summit in 1984 and the 17th G7 summit in 1991.[6] A new 35-foot-long table was built for the Long Gallery, where the main negotiating sessions were planned in 1991.[7]

In popular culture

The house was used for location shooting in the mystery adventure film National Treasure: Book of Secrets (2007). Sequences supposedly occurring in Buckingham Palace were filmed in the house. In the historical drama film The Young Victoria (2009), the house was used for filming of scenes that purportedly took place within the ballroom, a passage and the reception room of Buckingham Palace. The house was used for a similar reason for the historical drama film The King's Speech (2010). It also appears as the house of Lady Bracknell in the comedy of manners film The Importance of Being Earnest (2002). It was used as the interior of Buckingham Palace in the 2013 Christmas special of Downton Abbey.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lancaster House. |

References

- ↑ Historic England. "Lancaster House (Grade I) (1236546)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ↑ Historic England. "Details from image database (427576)". Images of England.

- 1 2 3 4 Stourton, James (16 October 2012). Great Houses of London. London: Francis Lincoln. ISBN 0711233667.

- ↑ Goldsmith, Belinda (1 March 2013). "Britain's government sells French wine to pay its drinks bill". Reuters. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ↑ Chopin in Britain PhD Thesis Durham University by Peter Willis pp138-147. He played some Mazurkas and a Mozart Duet

- ↑ Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA): Summit Meetings in the Past.

- ↑ Apple, Jr., R.W. (15 July 1991). "Reporter's Notebook; British Hosts, Being British, Plan an Understated Splendor". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

Bibliography

- Yorke, James (2001). Lancaster House: London's Greatest Town House. Merrell Publishers Ltd. ISBN 9780385601153.