Pneumatic tube

Pneumatic tubes (or capsule pipelines; also known as Pneumatic Tube Transport or PTT) are systems that propel cylindrical containers through networks of tubes by compressed air or by partial vacuum. They are used for transporting solid objects, as opposed to conventional pipelines, which transport fluids. Pneumatic tube networks gained acceptance in the late 19th and early 20th centuries for offices that needed to transport small, urgent packages (such as mail, paperwork, or money) over relatively short distances (within a building, or, at most within a city). Some installations grew to great complexity, but were mostly superseded. In some settings, such as hospitals, they remain widespread and have been further extended and developed in recent decades.[1]

A small number of pneumatic transportation systems were also built for larger cargo, to compete with more standard train and subway systems. However, these never gained popularity.

History

Historical use

Pneumatic capsule transportation was invented by William Murdoch. It was considered little more than a novelty until the invention of the capsule in 1836. The Victorians were the first to use capsule pipelines to transmit telegrams, to nearby buildings from telegraph stations.

In 1854, Josiah Latimer Clark was issued a patent "for conveying letters or parcels between places by the pressure of air and vacuum." In 1855, he installed a 220-yard (200 m) pneumatic system between the London Stock Exchange in Threadneedle Street, London, and the offices of the Electric Telegraph Company in Lothbury.[2]

While they are commonly used for small parcels and documents – including as cash carriers at banks or supermarkets[3] – they were originally proposed in the early 19th century for transport of heavy freight. It was once envisaged that networks of these massive tubes might be used to transport people.

Current use

The technology is still used on a smaller scale. While its use for communicating information has been superseded, pneumatic tubes are widely used for transporting small objects, or where convenience and speed in a local environment is useful.[1]

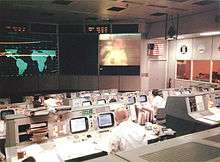

In the United States, drive-up banks often use pneumatic tubes to transport cash and documents between cars and tellers. Most hospitals have a computer-controlled pneumatic tube system to deliver drugs, documents and specimens to and from laboratories and nurses' stations.[1] Many factories use them to deliver parts quickly across large campuses. Many larger stores use systems to securely transport excess cash from checkout stands to back offices, and to send change back to cashiers. NASA's original Mission Control Center had pneumatic tubes connecting controller consoles with staff support rooms. Denver International Airport uses many pneumatic tube systems, including a 25 cm diameter system for moving aircraft parts to remote concourses, a 10 cm system for United Airlines ticketing, and a robust system in the parking toll collection system with an outlet at every booth.

Pneumatic tube systems are used in science, to transport samples during neutron activation analysis. Samples must be moved from the nuclear reactor core, in which they are bombarded with neutrons, to the instrument that records the resulting radiation. As some of the radioactive isotopes in the sample can have very short half-lives, speed is important. These systems may be automated, with a magazine of sample tubes that are moved into the reactor core in turn for a predetermined time, before being moved to the instrument station and finally to a container for storage and disposal.[4]

Until it closed in early 2011, a McDonald's in Edina, Minnesota claimed to be the "World's Only Pneumatic Air Drive-Thru," sending food from their strip-mall location to a drive-through in the middle of a parking lot.[5]

Technology editor Quentin Hardy notes that renewed interest in transmission of data by pneumatic tube accompanies discussions of digital network security,[6] and he cites research into London's forgotten pneumatic network.[7]

Applications

In postal service

Pneumatic post or pneumatic mail is a system to deliver letters through pressurized air tubes. It was invented by the Scottish engineer William Murdoch in the 19th century and was later developed by the London Pneumatic Despatch Company. Pneumatic post systems were used in several large cities starting in the second half of the 19th century (including an 1866 London system powerful and large enough to transport humans during trial runs – though not intended for that purpose), but later were largely abandoned.

A major network of tubes in Paris was in use until 1984, when it was abandoned in favor of computers and fax machines. In Prague, in the Czech Republic, the network extended approximately 60 kilometres (37 mi).[8]

Pneumatic post stations usually connect post offices, stock exchanges, banks and ministries. Italy was the only country to issue postage stamps (between 1913 and 1966) specifically for pneumatic post. Austria, France, and Germany issued postal stationery for pneumatic use.

Typical current applications are in banks, hospitals and supermarkets. Many large retailers use pneumatic tubes to transport cheques or other documents from cashiers to the accounting office.

- Historical use

- 1853: linking the London Stock Exchange to the city's main telegraph station (a distance of 220 yards (200 m) )

- 1861: in London with the London Pneumatic Despatch Company providing services from Euston railway station to the General Post Office and Holborn

- 1864: in Liverpool connecting the Electric and International Telegraph Company telegraph stations in Castle Street, Water Street and the Exchange Buildings[9]

- 1864: in Manchester to connect the Electric and International Telegraph Company central offices at York Street, with branch offices at Dulcie Buildings and Mosley Street[10]

- 1865: in Birmingham, installed by the Electric and International Telegraph Company between the New Exchange Buildings in Stephenson Place and their branch office in Temple Buildings, New Street.[11]

- 1865: in Berlin (until 1976), the Rohrpost, a system 400 kilometers in total length at its peak in 1940

- 1866: in Paris (until 1984, 467 kilometers in total length from 1934)

- 1871: in Dublin[12]

- 1875: in Vienna (until 1956)

- 1887: in Prague (until 2002 due to flooding), the Prague pneumatic post[13]

- 1893: the first North American system was established in Philadelphia by Postmaster General John Wanamaker, who had previously employed the technology at his department store. The system, which initially connected the downtown post offices, was later extended to the principal railroad stations, the stock exchanges, and many private businesses. It was operated by the United States Post Office Department which later opened similar systems in cities such as New York (connecting Brooklyn and Manhattan), Chicago, Boston, and St. Louis. The last of these closed in 1953.[14]

- other cities: Munich, Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires, Hamburg, Rome, Naples, Milan, Marseille, Melbourne, Tokyo, Osaka, Nagoya, Kobe

In public transportation

- 19th century

In 1812, George Medhurst first proposed, but never implemented, blowing passenger carriages through a tunnel.[15] Precursors of pneumatic tube systems for passenger transport, the atmospheric railway (for which the tube was laid between the rails, with a piston running in it suspended from the train through a sealable slot in the top of the tube) were operated as follows:[16]

- 1844–54: Dublin and Kingstown Railway's Dalkey Atmospheric Railway between Kingstown (Dún Laoghaire) and Dalkey, Ireland (1.75 mi (2.82 km))

- 1846–47: London and Croydon Railway between Croydon and New Cross, London, England (7.5 mi (12.1 km))

- 1847–48: Isambard Kingdom Brunel's South Devon Railway between Exeter and Newton Abbot, England (20 mi (32 km))

- 1847–60: Paris–Saint-Germain railway between Bois de Vésinet and Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France (2 km (1.2 mi))

In 1861, the London Pneumatic Despatch Company built a system large enough to move a person, although it was intended for parcels. The inauguration of the new Holborn Station on 10 October 1865 was marked by having the Duke of Buckingham, the chairman, and some company directors blown through the tube to Euston (a five-minute trip).

The 550-meter Crystal Palace pneumatic railway was exhibited at the Crystal Palace in 1864. This was a prototype for a proposed Waterloo and Whitehall Railway that would have run under the River Thames linking Waterloo and Charing Cross. Digging commenced in 1865 but was halted in 1868 due to financial problems.

In 1867 at the American Institute Fair in New York, Alfred Ely Beach demonstrated a 32.6 m long, 1.8 m diameter pipe that was capable of moving 12 passengers plus a conductor.[17] In 1869, the Beach Pneumatic Transit Company of New York secretly constructed a 95 m long, 2.7 m diameter pneumatic subway line under Broadway, to demonstrate the possibilities of the new transport mode.[17] The line only operated for a few months, closing after Beach was unsuccessful in getting permission to extend it – Boss Tweed, an influential local politician, did not want it to go ahead as he was intending to personally invest into competing schemes for an elevated rail line.[18]

- 20th century

In the 1960s, Lockheed and MIT with the United States Department of Commerce conducted feasibility studies on a vactrain system powered by ambient atmospheric pressure and "gravitational pendulum assist" to connect cities on the country's East Coast.[17] They calculated that the run between Philadelphia and New York City would average 174 meters per second, that is 626 km/h (388 mph). When those plans were abandoned as too expensive, Lockheed engineer L.K. Edwards founded Tube Transit, Inc. to develop technology based on "gravity-vacuum transportation". In 1967 he proposed a Bay Area Gravity-Vacuum Transit for California that would run alongside the then-under construction BART system. It was never built.

- 21st century

Research into trains running in partially evacuated tubes is continuing. For further information see Vactrain and Hyperloop.

In money transfer

In large retail stores, pneumatic tube systems were used to transport sales slips and money from the salesperson to a centralized "tube room", where cashiers could make change, reference credit records, and so on.[19]

Many banks with drive-throughs also use pneumatic tubes.[3]

In medicine

Many hospitals have pneumatic tube systems which send samples to laboratories.[1][20]

Technical characteristics

Modern systems (for smaller, i.e. "normal" tube diameters as used in the transport of small capsules) reach speeds of around 7.5 m (25 ft) per second, though some historical systems already achieved speeds of 10 m (33 ft) per second.[1][21] Further, modern systems can also be computer-controlled, allowing, among other things, the tracking of any specific capsule. Varying air pressures also allow capsules to brake slowly, removing the jarring arrival that used to characterise earlier systems and make them unsuitable for fragile contents.[1]

In fiction

When pneumatic tubes first came into use in the 19th century, they symbolized technological progress and it was imagined that they would be common in the future. Jules Verne's Paris in the Twentieth Century (1863) includes suspended pneumatic tube trains that stretch across the oceans. Albert Robida's The Twentieth Century (1882) describes a 1950s Paris where tube trains have replaced railways, pneumatic mail is ubiquitous, and catering companies compete to deliver meals on tap to people's homes through pneumatic tubes. Edward Bellamy's Looking Backward (1888) envisions the world of 2000 as interlinked with tubes for delivering goods,[22] while Michel Verne's An Express of the Future (1888) questions the sensibility of a transatlantic pneumatic subway.[23] In Michel & Jules Verne's The Day of an American Journalist in 2889 (1889) submarine tubes carry people faster than aero-trains and the Society for Supplying Food to the Home allows subscribers to receive meals pneumatically.[24]

Later, because of their use by governments and large businesses, tubes began to symbolize bureaucracy. In George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four, pneumatic tubes in the Ministry of Truth deliver newspapers to Winston's desk containing articles to be "rectified". Robert A. Heinlein's 1949 novella Gulf offered a more neutral view of their use in general postal delivery.

Beginning with the 42nd issue of 181-issue Doc Savage Magazine (The Midas Man, Volume VII, No. 6, Aug 1936), Doc Savage's penthouse on the 86th floor of an unnamed New York City skyscraper (implicitly the Empire State Building) is linked to his Hidalgo Trading Company warehouse-boathouse-hangar on the Hudson River waterfront by pneumatic bullet-car nicknamed the Flea Run, Go-Devil and Angel-Wagon due to its hundred-mile per hour speed and that plummets straight down from the penthouse ninety stories to a sub-basement, makes a 90° turn to travel a mile and a quarter (a little over two kilometers) 60 feet (18 meters) below 34th Street and then comes back up to ground floor of the warehouse, presumably at a shallower but still steep incline. The interior of the car is heavily padded, with four seats, one behind the other bobsled fashion. Since the car does not turn around, the seats are designed to rotate 180° so that the passengers always face in the direction of travel. The acceleration is such that, when traveling down the tube from the 86th Floor, no sensation of falling is experienced. The system is driven by enormous air compressors and compressed air receiver vessels housed on the roofs of both the skyscraper and the Hidalgo Trading Company.

In a sequence in the 1968 film Baisers volés (Stolen Kisses), François Truffaut shows the fast transportation of a letter through the underground pneumatic tubes system in Paris. (This scene was later parodied in The Simpsons episode "Marge Gets a Job".)

In 1985, the movie Brazil also used tubes (as well as other anachronistic-seeming technologies) to evoke the stagnation of bureaucracy.

At the start of each episode of the 1998 television series Fantasy Island, a darker version of the original, bookings for would-be visitors to the Island were sent to Mr. Roarke via a pneumatic tube from a dusty old travel agency.

The 1994 film version of The Shadow includes a sequence in which the camera follows a message capsule as it speeds through a pneumatic tube system. The implication is that the Shadow maintains a private network of tubes for the transportation of secret messages.

The failure of pneumatic tubes to live up to their potential as envisaged in previous centuries has placed them in the company of flying cars and dirigibles as ripe for ironic retro-futurism. The animated television series The Jetsons featured pneumatic tubes that people could step into and be sucked up and swiftly spat out at their destination. In the animated television series Futurama, set in the 31st century, large pneumatic tubes are used in cities for transporting people, whilst smaller ones are used to transport mail. The tubes in Futurama are also used to depict the endless confusion of bureaucracy: an immense network of pneumatic tubes connects all offices in New New York City to the "Central Bureaucracy", with all the capsules being deposited directly into a huge pile in the main filing room, with no sorting or organization.

In Ghostbusters II, the "river of slime" under New York city is found by the Ghostbusters boys to be flowing through an old pneumatic tube line – a reference to the Beach Pneumatic Transit tube.

In the 1998 PC game Grim Fandango, pneumatic tubes play a role at Manny's office.

In the American television show Lost, the Dharma Initiative's Pearl research station has a pneumatic tube system. The character Locke put his drawing of the blast door map in the tube without a capsule. It was sucked up into the tube, indicating the system still functioned. The tube from the Pearl leads to a capsule dump.

In Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five pneumatic tubes are used as a way to transport information from one place to the next when covering news articles.

In the popular video game BioShock, pneumatic tubes transport various items throughout the fictional city of Rapture. In Portal and Portal 2, two other popular games, Aperture Science uses Pneumatic tubes to transport larger-scale objects such as boxes of all kinds throughout their enrichment center.

Douglas Adams's 1998 computer game Starship Titanic features the "Succ-U-Bus" in almost every room –a pneumatic pipe transport system which goes all around the ship; players must understand and use the Succ-U-Bus in order to progress and solve the puzzles.

Umberto Eco in his novel The Prague Cemetery has one character, Simonini, send a "petit blue message by pneumatic post". Presumably these messages were on small pieces of blue paper.

In the 2004 Movie The Polar Express, 'The Pnuematic' transports elves and lead characters from the main control room to various places throughout the North Pole.

In the CBS series, Person of Interest, a pneumatic tube network is used to avoid tracking of communication by electronic means. The network is shown in the mafia war in the 21st episode of the fourth season, 'Asylum'.

In the 2014 Movie Kingsman: The Secret Service, a four-seat pneumatic tube shuttle is used to link the downtown tailors office to the country estate & training area.

See also

- Pipeline transport

- Prague pneumatic post, the world's last preserved pneumatic mail system

- Vactrain

- Foodtubes

- Garbage collection

- Lamson Engineering Company Ltd

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Gone with the wind: Tubes are whisking samples across hospital". Stanford School of Medicine. 2010-01-11. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- ↑ "Pneumatic Networks". Museum of Retrotechnology. 23 July 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- 1 2 Buxton, Andrew (2004). Cash Carriers in Shops. Princes Risborough: Shire Publications. ISBN 978-0-7478-0615-8.

- ↑ Becker, D.A. (22 June 10, 1998). "Characterization and use of the new NIST rapid pneumatic tube irradiation facility". Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry 233: 155–160. doi:10.1007/bf02389664. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Pneumatic Air Drive-Thru McDonald's". Waymarking website. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- ↑ Hardy, Quentin (March 6, 2015). "The Mechanical World". What We're Reading. The New York Times. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ↑ "On The Blower: London's Lost Pneumatic Messaging Tubes". Lapsed Historian. February 14, 2015. Archived from the original on March 4, 2015. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ↑ "Czech start wins 19th century technology". Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- ↑ "The Pneumatic Despatch Principle in Liverpool". Sheffield Daily Telegraph (England). 30 April 1864. Retrieved 14 February 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Pneumatics applied to Telegraphy". Cumberland and Westmorland Advertiser, and Penrith Literary Chronicle (England). 13 December 1864. Retrieved 14 February 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "The Pneumatic Desptach System". Birmingham Daily Gazette (England). 1 March 1865. Retrieved 14 February 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Postal Telegraph in Ireland". Clare Journal, and Ennis Advertiser (Ireland). 23 February 1871. Retrieved 14 February 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Prague's pneumatic post". Telefónica O2 Czech Republic. 2002. Archived from the original on 2010-01-09. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- ↑ Kyriakodis, Harry. "Pneumatic Philadelphia". Hidden City Philadelphia.

- ↑ George Medhurst, Calculations and remarks tending to prove the practicability ... of a plan for the rapid conveyance of goods and passengers upon an iron road through a tube of 30 feet in area, by the power and velocity of air, London: 1812

- ↑ Hadfield, Charles (1967). Atmospheric Railways. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-4107-3.

- 1 2 3 Bellows, Alan. "The Remarkable Pneumatic People-Mover". www.damninteresting.com. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ↑ Allen, Oliver E. "New York's Secret Subway". AmericanHeritage.com website. Archived from the original on 16 February 2010. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- ↑ Charles Augustus Sweetland, Department Store Accounts 1908, p. 70

- ↑ D. Hamill, Sean (2012-10-28). "UPMC constructing underground pneumatic tubes to link hospitals to new lab". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- ↑ "Capsule Pipelines – Mainland Europe". Capsu.org website. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- ↑ Bellamy, Edward (1888). Looking Backward, Chapter X.

- ↑ Verne, Michel (1888). An Express of the Future.

- ↑ Verne, Jules; Verne (1889). The Day of an American Journalist in 2889. Michel.

External links

London Midland Magazine – February 1963 – article on the Pneumatic Dispatch Railway in London

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pneumatic tube. |

- Site describing Pneumatic Trash and Linen Systems, with photos

- Describes Paris pneumatic post, also mentions others

- Dial Switches Message Tubes 1951 article that describes with photos and drawing the basics of how the system operates

- Site describing pneumatic post systems in England, France, Berlin, the US, and Prague, with photos

- Article describing the pneumatic post system in Prague

- Pneumatic mail article from the U.S. National Postal Museum

- The pneumatic dispatch... (1868) by Alfred Beach (scanned pages)

- Beach Pneumatic Alfred Beach's Pneumatic Subway and the beginnings of rapid transit in New York

- Futuristics: Pneumatic Transportation (contains historical illustrations)

- Capsule Pipelines: includes extensive historical documentation

- Components of a pneumatic tube system

- Pneumatic Tube System Builder: Aerocom Engineering

- Pneumatic Tube Transport developer: C.P.Bourg

- Archibald Williams, "Pneumatic Mail Tubes". Complete description and history in ordinary language. In The Romance of Modern Mechanism: With Interesting Descriptions in Non-Technical Language of Wonderful Machinery and Mechanical Devices and Marvellously Delicate Scientific Instruments, Etc., Etc. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1907. Reprinted by Nabu Press, 2010. ISBN 1-146-99537-7.

- Pneumatic Tube System - How it works

- Cash Railway Website: pneumatic tubes used for cash handling in shops

|