Lagrangian (field theory)

Lagrangian field theory is a formalism in classical field theory. It is the field theoretic analogue of Lagrangian mechanics. Lagrangian mechanics is used for discrete particles each with a finite number of degrees of freedom. Lagrangian field theory applies to continua and fields, which have an infinite number of degrees of freedom.

This article uses  for the Lagrangian density, and L for the Lagrangian.

for the Lagrangian density, and L for the Lagrangian.

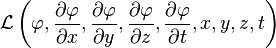

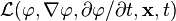

The Lagrangian mechanics formalism was generalized further to handle field theory. In field theory, the independent variable is replaced by an event in spacetime (x, y, z, t), or more generally still by a point s on a manifold. The dependent variables (q) are replaced by the value of a field at that point in spacetime φ(x, y, z, t) so that the equations of motion are obtained by means of an action principle, written as:

where the action,  , is a functional of the dependent variables φi(s) with their derivatives and s itself

, is a functional of the dependent variables φi(s) with their derivatives and s itself

and where s = { sα} denotes the set of n independent variables of the system, indexed by α = 1, 2, 3,..., n. Notice L is used in the case of one independent variable (t) and  is used in the case of multiple independent variables (usually four: x, y, z, t).

is used in the case of multiple independent variables (usually four: x, y, z, t).

Definitions

In Lagrangian field theory, the Lagrangian as a function of generalized coordinates is replaced by a Lagrangian density, a function of the fields in the system and their derivatives, and possibly the space and time coordinates themselves. In field theory, the independent variable t is replaced by an event in spacetime (x, y, z, t) or still more generally by a point s on a manifold.

Often, a "Lagrangian density" is simply referred to as a "Lagrangian".

Scalar fields

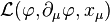

For one scalar field  , the Lagrangian density will take the form:[nb 1][1]

, the Lagrangian density will take the form:[nb 1][1]

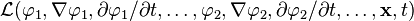

For many scalar fields

Vector fields, tensor fields, spinor fields

The above can be generalized for vector fields, tensor fields, and spinor fields. In physics fermions are described by spinor fields and bosons by tensor fields.

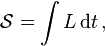

Action

The time integral of the Lagrangian is called the action denoted by S. In field theory, a distinction is occasionally made between the Lagrangian L, of which the time integral is the action

and the Lagrangian density  , which one integrates over all spacetime to get the action:

, which one integrates over all spacetime to get the action:

The spatial volume integral of the Lagrangian density is the Lagrangian, in 3d

Quantum field theories in particle physics, such as quantum electrodynamics, are usually described in terms of  , and the terms in this form of the Lagrangian translate quickly to the rules used in evaluating Feynman diagrams.

, and the terms in this form of the Lagrangian translate quickly to the rules used in evaluating Feynman diagrams.

Notice that, in the presence of gravity or when using general curvilinear coordinates, the Lagrangian density  will include a factor of √g or its equivalent to ensure that it is a scalar density so that the integral will be invariant.

will include a factor of √g or its equivalent to ensure that it is a scalar density so that the integral will be invariant.

Mathematical formalism

Suppose we have an n-dimensional manifold, M, and a target manifold, T. Let  be the configuration space of smooth functions from M to T.

be the configuration space of smooth functions from M to T.

In field theory, M is the spacetime manifold and the target space is the set of values the fields can take at any given point. For example, if there are  real-valued scalar fields,

real-valued scalar fields,  , then the target manifold is

, then the target manifold is  . If the field is a real vector field, then the target manifold is isomorphic to

. If the field is a real vector field, then the target manifold is isomorphic to  . There is actually a much more elegant way using tangent bundles over M, but we will just stick to this version.

. There is actually a much more elegant way using tangent bundles over M, but we will just stick to this version.

Consider a functional,

,

,

called the action. Physical considerations require it be a mapping to  (the set of all real numbers), not

(the set of all real numbers), not  (the set of all complex numbers).

(the set of all complex numbers).

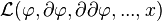

In order for the action to be local, we need additional restrictions on the action. If  , we assume

, we assume ![\mathcal{S}[\varphi]](../I/m/0c319fd2b821166996506bb1e04ab578.png) is the integral over M of a function of

is the integral over M of a function of  , its derivatives and the position called the Lagrangian,

, its derivatives and the position called the Lagrangian,  . In other words,

. In other words,

It is assumed below, in addition, that the Lagrangian depends on only the field value and its first derivative but not the higher derivatives.

Given boundary conditions, basically a specification of the value of  at the boundary if M is compact or some limit on

at the boundary if M is compact or some limit on  as x → ∞ (this will help in doing integration by parts), the subspace of

as x → ∞ (this will help in doing integration by parts), the subspace of  consisting of functions,

consisting of functions,  , such that all functional derivatives of S at

, such that all functional derivatives of S at  are zero and

are zero and  satisfies the given boundary conditions is the subspace of on shell solutions.

satisfies the given boundary conditions is the subspace of on shell solutions.

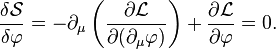

The solution is given by the Euler–Lagrange equations (thanks to the boundary conditions),

The left hand side is the functional derivative of the action with respect to  .

.

Examples

To go with the section on test particles above, here are the equations for the fields in which they move. The equations below pertain to the fields in which the test particles described above move and allow the calculation of those fields. The equations below will not give you the equations of motion of a test particle in the field but will instead give you the potential (field) induced by quantities such as mass or charge density at any point  . For example, in the case of Newtonian gravity, the Lagrangian density integrated over spacetime gives you an equation which, if solved, would yield

. For example, in the case of Newtonian gravity, the Lagrangian density integrated over spacetime gives you an equation which, if solved, would yield  . This

. This  , when substituted back in equation (1), the Lagrangian equation for the test particle in a Newtonian gravitational field, provides the information needed to calculate the acceleration of the particle.

, when substituted back in equation (1), the Lagrangian equation for the test particle in a Newtonian gravitational field, provides the information needed to calculate the acceleration of the particle.

Newtonian gravity

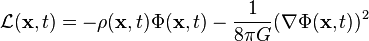

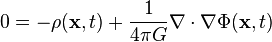

The Lagrangian (density) is  in J·m−3. The interaction term mΦ is replaced by a term involving a continuous mass density ρ in kg·m−3. This is necessary because using a point source for a field would result in mathematical difficulties. The resulting Lagrangian for the classical gravitational field is:

in J·m−3. The interaction term mΦ is replaced by a term involving a continuous mass density ρ in kg·m−3. This is necessary because using a point source for a field would result in mathematical difficulties. The resulting Lagrangian for the classical gravitational field is:

where G in m3·kg−1·s−2 is the gravitational constant. Variation of the integral with respect to Φ gives:

Integrate by parts and discard the total integral. Then divide out by δΦ to get:

and thus

which yields Gauss's law for gravity.

Einstein Gravity

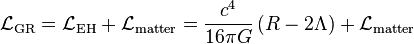

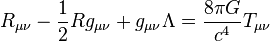

The Lagrange density for general relativity in the presence of matter fields is

is the curvature scalar, which is the Ricci tensor contracted with the metric tensor, and the Ricci tensor is the Riemann tensor contracted with a Kronecker delta. The integral of

is the curvature scalar, which is the Ricci tensor contracted with the metric tensor, and the Ricci tensor is the Riemann tensor contracted with a Kronecker delta. The integral of  is known as the Einstein-Hilbert action. The Riemann tensor is the tidal force tensor, and is constructed out of Christoffel symbols and derivatives of Christoffel symbols, which are the gravitational force field. Plugging this Lagrangian into the Euler-Lagrange equation and taking the metric tensor

is known as the Einstein-Hilbert action. The Riemann tensor is the tidal force tensor, and is constructed out of Christoffel symbols and derivatives of Christoffel symbols, which are the gravitational force field. Plugging this Lagrangian into the Euler-Lagrange equation and taking the metric tensor  as the field, we obtain the Einstein field equations

as the field, we obtain the Einstein field equations

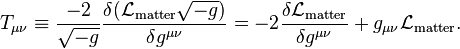

The last tensor is the energy momentum tensor and is defined by

is the determinant of the metric tensor when regarded as a matrix.

is the determinant of the metric tensor when regarded as a matrix.  is the Cosmological constant. Generally, in general relativity, the integration measure of the action of Lagrange density is

is the Cosmological constant. Generally, in general relativity, the integration measure of the action of Lagrange density is  . This makes the integral coordinate independent, as the root of the metric determinant is equivalent to the Jacobian determinant. The minus sign is a consequence of the metric signature (the determinant by itself is negative).[2]

. This makes the integral coordinate independent, as the root of the metric determinant is equivalent to the Jacobian determinant. The minus sign is a consequence of the metric signature (the determinant by itself is negative).[2]

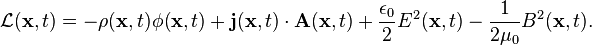

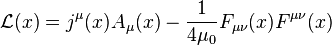

Electromagnetism in special relativity

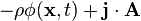

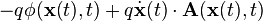

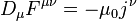

The interaction terms

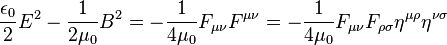

are replaced by terms involving a continuous charge density ρ in A·s·m−3 and current density  in A·m−2. The resulting Lagrangian for the electromagnetic field is:

in A·m−2. The resulting Lagrangian for the electromagnetic field is:

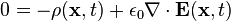

Varying this with respect to ϕ, we get

which yields Gauss' law.

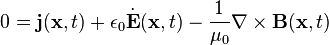

Varying instead with respect to  , we get

, we get

which yields Ampère's law.

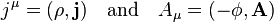

Using tensor notation, we can write all this more compactly. The term  is actually the inner product of two four-vectors. We package the charge density into the current 4-vector and the potential into the potential 4-vector. These two new vectors are

is actually the inner product of two four-vectors. We package the charge density into the current 4-vector and the potential into the potential 4-vector. These two new vectors are

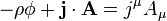

We can then write the interaction term as

Additionally, we can package the E and B fields into what is known as the electromagnetic tensor  .

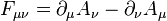

We define this tensor as

.

We define this tensor as

The term we are looking out for turns out to be

We have made use of the Minkowski metric to raise the indices on the EMF tensor. In this notation, Maxwell's equations are

where ε is the Levi-Civita tensor. So the Lagrange density for electromagnetism in special relativity written in terms of Lorentz vectors and tensors is

In this notation it is apparent that classical electromagnetism is a Lorentz-invariant theory. By the equivalence principle, it becomes simple to extend the notion of electromagnetism to curved spacetime.[3][4]

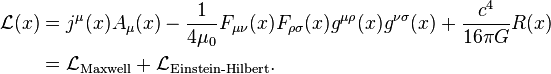

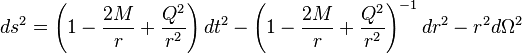

Electromagnetism in general relativity

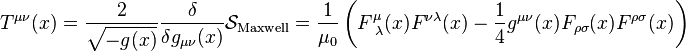

The Lagrange density of electromagnetism in general relativity also contains the Einstein-Hilbert action from above. The pure electromagnetic Lagrangian is precisely a matter Lagrangian  . The Lagrangian is

. The Lagrangian is

This Lagrangian is obtained by simply replacing the Minkowski metric in the above flat Lagrangian with a more general (possibly curved) metric  . We can generate the Einstein Field Equations in the presence of an EM field using this lagrangian. The energy-momentum tensor is

. We can generate the Einstein Field Equations in the presence of an EM field using this lagrangian. The energy-momentum tensor is

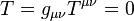

It can be shown that this energy momentum tensor is traceless, i.e. that

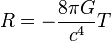

If we take the trace of both sides of the Einstein Field Equations, we obtain

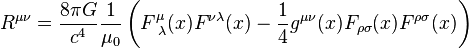

So the tracelessness of the energy momentum tensor implies that the curvature scalar in an electromagnetic field vanishes. The Einstein equations are then

Additionally, Maxwell's equations are

where  is the covariant derivative. For free space, we can set the current tensor equal to zero,

is the covariant derivative. For free space, we can set the current tensor equal to zero,  . Solving both Einstein and Maxwell's equations around a spherically symmetric mass distribution in free space leads to the Reissner-Nordstrom charged black hole, with the defining line element (written in natural units and with charge Q):[5]

. Solving both Einstein and Maxwell's equations around a spherically symmetric mass distribution in free space leads to the Reissner-Nordstrom charged black hole, with the defining line element (written in natural units and with charge Q):[5]

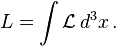

Electromagnetism using differential forms

Using differential forms, the electromagnetic action S in vacuum on a (pseudo-) Riemannian manifold  can be written (using natural units, c = ε0 = 1) as

can be written (using natural units, c = ε0 = 1) as

Here, A stands for the electromagnetic potential 1-form, J is the current 1-form, F is the field strength 2-form and the star denotes the Hodge star operator. This is exactly the same Lagrangian as in the section above, except that the treatment here is coordinate-free; expanding the integrand into a basis yields the identical, lengthy expression. Note that with forms, an additional integration measure is not necessary because forms have coordinate differentials built in. Variation of the action leads to

These are Maxwell's equations for the electromagnetic potential. Substituting F = dA immediately yields the equation for the fields,

because F is an exact form.

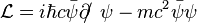

Dirac Lagrangian

The Lagrangian density for a Dirac field is:[6]

where ψ is a Dirac spinor (annihilation operator),  is its Dirac adjoint (creation operator), and

is its Dirac adjoint (creation operator), and  is Feynman slash notation for

is Feynman slash notation for  .

.

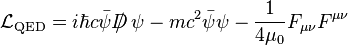

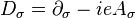

Quantum electrodynamic Lagrangian

The Lagrangian density for QED is:

where  is the electromagnetic tensor, D is the gauge covariant derivative, and

is the electromagnetic tensor, D is the gauge covariant derivative, and  is Feynman notation for

is Feynman notation for  with

with  where

where  is the electromagnetic four-potential.

is the electromagnetic four-potential.

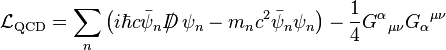

Quantum chromodynamic Lagrangian

The Lagrangian density for quantum chromodynamics is:[7][8][9]

where D is the QCD gauge covariant derivative,

n = 1, 2, ...6 counts the quark types, and  is the gluon field strength tensor.

is the gluon field strength tensor.

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ It is a standard abuse of notation to abbreviate all the derivatives and coordinates in the Lagrangian density as follows:

Notes

- ↑ Mandl F., Shaw G., Quantum Field Theory, chapter 2

- ↑ Zee, A. (2013). Einstein gravity in a nutshell. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 344–390. ISBN 9780691145587.

- ↑ Zee, A. (2013). Einstein gravity in a nutshell. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 244–253. ISBN 9780691145587.

- ↑ Mexico, Kevin Cahill, University of New (2013). Physical mathematics (Repr. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107005211.

- ↑ Zee, A. (2013). Einstein gravity in a nutshell. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 381–383, 477–478. ISBN 9780691145587.

- ↑ Itzykson-Zuber, eq. 3-152

- ↑ http://www.fuw.edu.pl/~dobaczew/maub-42w/node9.html

- ↑ http://smallsystems.isn-oldenburg.de/Docs/THEO3/publications/semiclassical.qcd.prep.pdf

- ↑ http://www-zeus.physik.uni-bonn.de/~brock/teaching/jets_ws0405/seminar09/sluka_quark_gluon_jets.pdf

![\mathcal{S}\left[\varphi_i\right] = \int{ \mathcal{L} \left(\varphi_i (s), \frac{\partial \varphi_i (s)}{\partial s^\alpha}, s^\alpha\right) \, \mathrm{d}^n s }](../I/m/a8ada7e2e3a2eafb5bac52b6ae998890.png)

![\mathcal{S} [\varphi] = \int \mathcal{L} (\varphi,\nabla\varphi,\partial\varphi/\partial t , \mathbf{x},t) \, \mathrm{d}^3 \mathbf{x} \mathrm{d}t .](../I/m/477b8d62e3d4742b1f2efe48a8dd76ea.png)

![\forall\varphi\in\mathcal{C}, \ \ \mathcal{S}[\varphi]\equiv\int_M \mathrm{d}^nx \mathcal{L} \big( \varphi(x),\partial\varphi(x),\partial\partial\varphi(x), ...,x \big).](../I/m/a8dfb1ebe45498e228103ee0753c7fe4.png)

![\mathcal S[\mathbf{A}] = \int_{\mathcal{M}} \left(-\frac{1}{2}\,\mathbf{F} \wedge \star\mathbf{F} + \mathbf{A} \wedge\star \mathbf{J}\right) .](../I/m/aed8024178fc3125ef96615977ec262f.png)