Red Fort

| Red Fort लाल क़िला لال قلعہ | |

|---|---|

|

View towards the Lahori Gate of the Red Fort | |

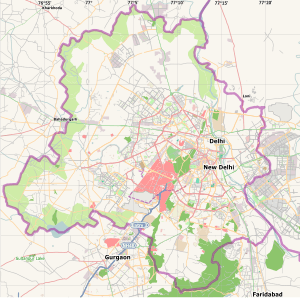

| Location | Delhi, India |

| Coordinates | 28°39′22″N 77°14′28″E / 28.656°N 77.241°ECoordinates: 28°39′22″N 77°14′28″E / 28.656°N 77.241°E |

| Built | 1648 |

| Architect | Ustad Ahmad Lahauri |

| Architectural style(s) | Indian architecture |

| Official name: Red Fort Complex | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iii, vi |

| Designated | 2007 (31st session) |

| Reference no. | 231 |

| State Party | India |

| Region | Asia-Pacific |

Location in Delhi, India, Asia | |

The Red Fort was the residence of the Mughal emperor of India for nearly 200 years, until 1857. It is located in the centre of Delhi and houses a number of museums. In addition to accommodating the emperors and their households, it was the ceremonial and political centre of Mughal government and the setting for events critically impacting the region.[1]

Constructed in 1648 by the fifth Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan as the palace of his fortified capital Shahjahanabad,[2] the Red Fort is named for its massive enclosing walls of red sandstone and is adjacent to the older Salimgarh Fort, built by Islam Shah Suri in 1546. The imperial apartments consist of a row of pavilions, connected by a water channel known as the Stream of Paradise (Nahr-i-Behisht). The fort complex is considered to represent the zenith of Mughal creativity under Shah Jahan and although the palace was planned according to Islamic prototypes, each pavilion contains architectural elements typical of Mughal buildings that reflect a fusion of Timurid and Persian traditions. The Red Fort’s innovative architectural style, including its garden design, influenced later buildings and gardens in Delhi, Rajasthan, Punjab, Kashmir, Braj, Rohilkhand and elsewhere.[1] With the Salimgarh Fort, it was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2007 as part of the Red Fort Complex.[1][3]

On Independence Day (15 August), the Prime Minister of India hoists the 'tricolor' national flag at the main gate of the fort and delivers a nationally-broadcast speech from its ramparts.[4]

Name

Its English name, "Red Fort", is a translation of the Hindustani Lāl Qila (Urdu: لال قلعہ, Hindi: लाल क़िला) deriving from its red-sandstone walls. As the residence of the imperial family, the fort was originally known as the "Blessed Fort" (Qila-i-Mubārak, Urdu: قلعہ مبارک, Hindi: क़िला मुबारक).[5][6] Agra Fort is also called Lāl Qila'.

History

Emperor Shah Jahan commissioned construction of the Red Fort in 1638, when he decided to shift his capital from Agra to Delhi. Originally red and white, the Shah's favourite colours,[7] its design is credited to architect Ustad Ahmad Lahauri, who also constructed the Taj Mahal.[8][9] The fort lies along the Yamuna River, which fed the moats surrounding most of the walls.[10] Construction began in the sacred month of Muharram, on 13 May 1638.[11]:01 Supervised by Shah Jahan, it was completed in 1648.[12][13] Unlike other Mughal forts, the Red Fort's boundary walls are asymmetrical to contain the older Salimgarh Fort.[11]:04 The fortress-palace was a focal point of the medieval city of Shahjahanabad, which is present-day Old Delhi. Its planning and aesthetics represent the zenith of Mughal creativity prevailing during Shah Jahan's reign. His successor Aurangzeb added the Pearl Mosque to the emperor's private quarters, constructing barbicans in front of the two main gates to make the entrance to the palace more circuitous.[11]:08

The administrative and fiscal structure of the Mughal dynasty declined after Aurangzeb, and the 18th century saw a degeneration of the palace. When Jahandar Shah took over the Red Fort in 1712, it had been without an emperor for 30 years. Within a year of beginning his rule, Shah was murdered and replaced by Farrukhsiyar. To raise money, the silver ceiling of the Rang Mahal was replaced by copper during this period. Muhammad Shah, known as 'Rangila' (the Colourful) for his interest in art, took over the Red Fort in 1719. In 1739, Persian emperor Nadir Shah easily defeated the Mughal army, plundering the Red Fort including the Peacock Throne. Nadir Shah returned to Persia after three months, leaving a destroyed city and a weakened Mughal empire to Muhammad Shah.[11]:09 The internal weakness of the Mughal empire made the Mughals titular heads of Delhi, and a 1752 treaty made the Marathas protectors of the throne at Delhi.[14][15] The 1758 Maratha conquest of Lahore and Peshawar[16] placed them in conflict with Ahmad Shah Durrani.[17][18] In 1760, the Marathas removed and melted the silver ceiling of the Diwan-i-Khas to raise funds for the defence of Delhi from the armies of Ahmed Shah Durrani.[19][20] In 1761, after the Marathas lost the third battle of Panipat, Delhi was raided by Ahmed Shah Durrani. Ten years later, Shah Alam ascended the throne in Delhi with Maratha support.[11]:10 In 1783 the Sikh Misl Karorisinghia, led by Baghel Singh Dhaliwal, conquered Delhi and the Red Fort. The Sikhs agreed to restore Shah Alam as emperor and retreat from the fort if the Mughals would build and protect seven Gurudwaras in Delhi for the Sikh gurus.[21]

During the Second Anglo-Maratha War in 1803, forces of British East India Company defeated Maratha forces in the Battle of Delhi; this ended Maratha rule of the city and their control of the Red Fort.[22] After the battle, the British took over the administration of Mughal territories and installed a Resident at the Red Fort.[11]:11 The last Mughal emperor to occupy the fort, Bahadur Shah II, became a symbol of the 1857 rebellion against the British in which the residents of Shahjahanbad participated.[11]:15

Despite its position as the seat of Mughal power and its defensive capabilities, the Red Fort was not defended during the 1857 uprising against the British. After the rebellion failed, Bahadur Shah II left the fort on 17 September and was apprehended by British forces. He returned to Red Fort as a prisoner of the British, was tried in 1858 and exiled to Rangoon on 7 October of that year.[23] With the end of Mughal reign, the British sanctioned the systematic plunder of valuables from the fort's palaces. All furniture was removed or destroyed; the harem apartments, servants' quarters and gardens were destroyed, and a line of stone barracks built.[24] Only the marble buildings on the east side at the imperial enclosure escaped complete destruction, but were looted and damaged. While the defensive walls and towers were relatively unharmed, more than two-thirds of the inner structures were destroyed by the British. Lord Curzon, Viceroy of India from 1899–1905, ordered repairs to the fort including reconstruction of the walls and the restoration of the gardens complete with a watering system.[25]

Most of the jewels and artworks of the Red Fort were looted and stolen during Nadir Shah's invasion of 1747 and again after the failed Indian Rebellion of 1857 against the British colonialists. They were eventually sold to private collectors or the British Museum, British Library and the Victoria and Albert Museum. For example, the Koh-i-Noor diamond, the jade wine cup of Shah Jahan and the crown of Bahadur Shah II are all currently located in London. Various requests for restitution have so far been rejected by the British government.[26]

1911 saw the visit of the British king and queen for the Delhi Durbar. In preparation of the visit, some buildings were restored. The Red Fort Archaeological Museum was also moved from the drum house to the Mumtaz Mahal.

The INA trials, also known as the Red Fort Trials, refer to the courts-martial of a number of officers of the Indian National Army. The first was held between November and December 1945 at the Red Fort.

On 15 August 1947, the first Prime Minister of India Jawaharlal Nehru raised the Indian national flag above the Lahore Gate. On each subsequent Independence Day, the prime minister has raised the flag and given a speech that is broadcast nationally.[27]

After Indian Independence the site experienced few changes, and the Red Fort continued to be used as a military cantonment. A significant part of the fort remained under Indian Army control until 22 December 2003, when it was given to the Archaeological Survey of India for restoration.[28][29] In 2009 the Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan (CCMP), prepared by the Archaeological Survey of India under Supreme Court directions to revitalise the fort, was announced.[30][31][32]

The fort today

Every year on India's Independence Day (15 August), the Prime Minister of India hoists the national flag at the Red Fort and delivers a nationally-broadcast speech from its ramparts.[4] The Red Fort, the largest monument in Delhi,[33] is one of its most popular tourist destinations[34] and attracts thousands of visitors every year.[35]

A sound and light show describing Mughal history is a tourist attraction in the evenings. The major architectural features are in mixed condition; the extensive water features are dry. Some buildings are in fairly-good condition, with their decorative elements undisturbed; in others, the marble inlaid flowers have been removed by looters. The tea house, although not in its historical state, is a working restaurant. The mosque and hamam or Turkish Bath are closed to the public, although visitors can peer through their glass windows or marble latticework. Walkways are crumbling, and public toilets are available at the entrance and inside the park.

The Lahore Gate entrance leads to a mall with jewellery and craft stores. There is also a museum of "blood paintings", depicting young 20th-century Indian martyrs and their stories, an archaeological museum and an Indian war-memorial museum.

Security

To prevent terrorist attacks, security is especially tight around the Red Fort on the eve of Indian Independence Day. Delhi Police and paramilitary personnel keep watch on neighbourhoods around the fort, and National Security Guard sharpshooters are deployed on high-rises near the fort.[36][37] The airspace around the fort is a designated no-fly zone during the celebration to prevent air attacks,[38] and safe houses exist in nearby areas to which the Prime Minister and other Indian leaders may retreat in the event of an attack.[36]

The fort was the site of a terrorist attack on 22 December 2000, carried out by six Lashkar-e-Toiba members. Two soldiers and a civilian were killed in what the news media described as an attempt to derail India-Pakistan peace talks.[39][40]

Architecture

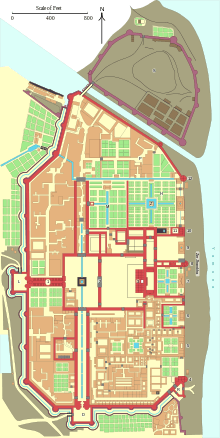

The Red Fort has an area of 254.67 acres (103.06 ha) enclosed by 2.41 kilometres (1.50 mi) of defensive walls,[2] punctuated by turrets and bastions and varying in height from 18 metres (59 ft) on the river side to 33 metres (108 ft) on the city side. The fort is octagonal, with the north-south axis longer than the east-west axis. The marble, floral decorations and double domes in the fort's buildings exemplify later Mughal architecture.[41]

It showcases a high level of ornamentation, and the Kohinoor diamond was reportedly part of the furnishings. The fort's artwork synthesises Persian, European and Indian art, resulting in a unique Shahjahani style rich in form, expression and colour. Red Fort is one of the building complexes of India encapsulating a long period of history and its arts. Even before its 1913 commemoration as a monument of national importance, efforts were made to preserve it for posterity.

The Lahori and Delhi Gates were used by the public, and the Khizrabad Gate was for the emperor.[11]:04 The Lahore Gate is the main entrance, leading to a domed shopping area known as the Chatta Chowk (covered bazaar).[41]

Major structures

The most important surviving structures are the walls and ramparts, the main gates, the audience halls and the imperial apartments on the eastern riverbank.[42]

Chawari Bazar

Chawari Bazar is located infront of Red Fort.

Lahori Gate

The Lahori Gate is the main gate to the Red Fort, named for its orientation towards the city of Lahore. During Aurangzeb's reign, the beauty of the gate was spoiled by the addition of bastions, Shahjahan described this as "a veil drawn across the face of a beautiful woman".[43][44][45] Every Indian Independence Day since 1947, the national flag has flown and the Prime Minister has made a speech from its ramparts.

Delhi Gate

The Delhi Gate is the southern public entrance and in layout and appearance similar to the Lahori Gate. Two life-size stone elephants on either side of the gate face each other. These were renewed by Lord Curzon in 1903 after their earlier demolition by Aurangzeb.[46]

Water Gate

A minor gate, the Water Gate is at the southeastern end of the walls. It was formerly on the riverbank; although the river has changed course since the fort's construction, the name has remained.

Chhatta Chowk

Adjacent to the Lahori Gate is the Chhatta Chowk, where silk, jewellery and other items for the imperial household were sold during the Mughal period. The bazaar leads to an open outer court, where it crosses the large north-south street which originally divided the fort's military functions (to the west) from the palaces (to the east). The southern end of the street is the Delhi Gate.

Naubat Khana

The vaulted arcade of the Chhatta Chowk ends in the centre of the outer court, which measured 540 by 360 feet (160 m × 110 m).[47] The side arcades and central tank were destroyed after the 1857 rebellion.

In the east wall of the court stands the now-isolated Naubat Khana (also known as Nakkar Khana), the drum house. Music was played at scheduled times daily next to a large gate, where everyone except royalty was required to dismount.

Diwan-i-Aam

The inner main court to which the Nakkar Khana led was 540 feet (160 m) wide and 420 feet (130 m) deep, surrounded by guarded galleries.[47] On the far side is the Diwan-i-Aam, the Public Audience Hall.

The hall's columns and engrailed arches exhibit fine craftsmanship, and the hall was originally decorated with white chunam stucco.[47] In the back in the raised recess the emperor gave his audience in the marble balcony (jharokha).

The Diwan-i-Aam was also used for state functions.[41] The courtyard (mardana) behind it leads to the imperial apartments.

Nahr-i-Behisht

The imperial apartments consist of a row of pavilions on a raised platform along the eastern edge of the fort, overlooking the Yamuna. The pavilions are connected by a canal, known as the Nahr-i-Behisht ("Stream of Paradise"), running through the centre of each pavilion. Water is drawn from the Yamuna via a tower, the Shahi Burj, at the northeast corner of the fort. The palace is designed to emulate paradise as described in the Quran. In the riverbed below the imperial apartments and connected buildings was a space known as zer-jharokha ("beneath the latticework").[47]

Mumtaz Mahal

The two southernmost pavilions of the palace are zenanas (women's quarters), consisting of the Mumtaz Mahal and the larger Rang Mahal. The Mumtaz Mahal houses the Red Fort Archaeological Museum.

Rang Mahal

The Rang Mahal housed the emperor's wives and mistresses. Its name means "Palace of Colours", since it was brightly painted and decorated with a mosaic of mirrors. The central marble pool is fed by the Nahr-i-Behisht.

Khas Mahal

The Khas Mahal was the emperor's apartment. Connected to it is the Muthamman Burj, an octagonal tower where he appeared before the people waiting on the riverbank.This was done mostly by all the kings present at that time.

Diwan-i-Khas

A gate on the north side of the Diwan-i-Aam leads to the innermost court of the palace (Jalau Khana) and the Diwan-i-Khas (Hall of Private Audience). It is constructed of white marble, inlaid with precious stones. The once-silver ceiling has been restored in wood. François Bernier described seeing the jewelled Peacock Throne here during the 17th century. At either end of the hall, over the two outer arches, is an inscription by Persian poet Amir Khusrow:

If heaven can be on the face of the earth,

It is this, it is this, it is this.

— "World Heritage Site – Red Fort, Delhi; Diwan-i-Khas". Archaeological Survey of India. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

Hammam

The hammam were the imperial baths, consisting of three domed rooms floored with white marble.

Baoli

The baoli or step-well, believed to pre-date Red Fort, is one of the few monuments that were not demolished by the British after the Indian Rebellion of 1857. The chambers within the baoli were converted into prison. During the Indian National Army Trials or Red Fort Trials in 1945-46, it housed Indian National Army officers Colonel Shah Nawaz Khan, Colonel Prem Kumar Sahgal and Colonel Gurbaksh Singh Dhillon. Red Fort Baoli is uniquely designed with two sets of staircases leading down to the well.[48]

Moti Masjid

West of the hammam is the Moti Masjid, the Pearl Mosque. A later addition, it was built in 1659 as a private mosque for Aurangzeb. It is a small, three-domed mosque carved in white marble, with a three-arched screen leading down to the courtyard.[49]

Hira Mahal

The Hira Mahal is a pavilion on the southern edge of the fort, built under Bahadur Shah II and at the end of the Hayat Baksh garden. The Moti Mahal on the northern edge, a twin building, was destroyed during (or after) the 1857 rebellion.

Shahi Burj

The Shahi Burj was the emperor's main study of the; its name means "Emperor's Tower", and it originally had a chhatri on top. Heavily damaged, the tower is undergoing reconstruction. In front of it is a marble pavilion added by Aurangzeb.

Hayat Bakhsh Bagh

The Hayat Bakhsh Bagh is the "Life-Bestowing Garden" in the northeast part of the complex. It features a reservoir (now dry) and channels, and at each end is a white marble pavilion (Savon and Bhadon). In the centre of the reservoir is the red-sandstone Zafar Mahal, added about 1842 under Bahadur Shah II.[50]

Smaller gardens (such as the Mehtab Bagh or Moonlight Garden) existed west of it, but were destroyed when the British barracks were built.[11]:07 There are plans to restore the gardens. Beyond these, the road to the north leads to an arched bridge and the Salimgarh Fort.

Princes' quarter

North of the Hayat Bakhsh Bagh and the Shahi Burj is the quarter of the imperial princes. This was used by member of the Mughal royal family and was largely destroyed by the British forces after the rebellion. One of the palaces was converted into a tea house for the soldiers.

Freedom Struggle Museum [Swatantrata Sangram Sangrahalaya]

Considering the role the Red Fort has played in the freedom struggle Swatantrata Sangram Sanghralaya was set up in one of the double storeyed army barracks in 1995. The museum provides a glimpse of major phases of India's struggle for freedom, from the First War of Independence of 1857 to India's Independence in 1947. In the museum, the history of the freedom struggle is depicted through photographs, documents, paintings, lithographs and objects like guns, pistols, swords, shields, badges, medals, dioramas, sculptures etc.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Red Fort Complex". World Heritage List. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- 1 2 N. L. Batra (May 2008). Delhi's Red Fort by the Yamuna. Niyogi Books. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ↑ "Red Fort was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2007". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on 29 April 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- 1 2 "Singh becomes third PM to hoist flag at Red Fort for 9th time". Business Standard. 15 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ↑ William M. Spellman (1 April 2004). Monarchies 1000–2000. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-087-0. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ↑ Mehrdad Kia; Elizabeth H. Oakes (1 November 2002). Social Science Resources in the Electronic Age. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-57356-474-8. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ↑ Nelson, Dean (20 May 2011). "Delhi's Red Fort was originally white". The Daily Telegraph (UK).

- ↑ "Ustad Ahmad Oxford Reference". doi:10.1093/oi/authority.20110810104325668 (inactive 2015-01-01).

- ↑ "building the Taj – who designed the Taj Mahal". PBS. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ↑ "Red Fort lies along the River Yamuna". Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Comprehensive Conservation Management Plan for Red Fort, Delhi" (PDF). Archaeological Survey of India. March 2009. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ↑ Controversy: Though this fort was thought to have been built in 1639, there are documents and a painting available of Shah Jahan receiving the Persian ambassador in 1638 at the jharokha in the Diwan-i-Aam in the Red fort. This painting preserved in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, was reproduced in the Illustrated Weekly of India (page 32) of 14 March 1971. However the painting shows the jharokha at Lahore, and not Delhi. See R. Nath's History of Mughal Architecture; Abhinav Publications, 2006..

- ↑ Pinto, Xavier; Myall, E. G. (2009). Glimpses of History. Frank Brothers. p. 129. ISBN 978-81-8409-617-0.

- ↑ Mehta, J. L. (2005). Advanced Study in the History of Modern India: Volume One: 1707 – 1813. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 134. ISBN 978-1-932705-54-6.

- ↑ Jayapalan, N. (2001). History of India. Atlantic Publishers & Distri. p. 249. ISBN 978-81-7156-928-1.

- ↑ Advanced Study in the History of Modern India: 1707 – 1813 – Jaswant Lal Mehta – Google Books. Google Books. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ↑ Roy, Kaushik. India's Historic Battles: From Alexander the Great to Kargil. Permanent Black, India. pp. 80–81. ISBN 978-81-78241-09-8.

- ↑ Elphinstone, Mountstuart (1841). History of India. John Murray, London. p. 276.

- ↑ Kulkarni, Uday S. (2012). Solstice at Panipat, 14 January 1761. Pune: Mula Mutha Publishers. p. 345. ISBN 978-81-921080-0-1.

- ↑ Kumar Maheshwari, Kamalesh; Wiggins, Kenneth W. (1989). Maratha Mints and Coinage. Indian Institute of Research in Numismatic Studies. p. 140.

- ↑ Murphy, Anne (2012). The Materiality of the Past: History and Representation in Sikh Tradition. Oxford University Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-19-991629-0.

- ↑ Mayaram, Shail (2003). Against History, Against State: Counterperspectives from the Margins. Columbia University Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-231-12731-8. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ↑ Mody, Krutika. "Bahadur Shah II "Zafar"'s significance with Red Fort". Archived from the original on 2 September 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ↑ William Dalrymple. "Introduction". The Last Mughal. Penguin. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-143-10243-4.

- ↑ Eugenia W Herbert (2013). Flora's Empire: British Gardens in India. Penguin Books Limited. p. 333. ISBN 978-81-8475-871-9.

- ↑ Nelson, Sara C. (21 February 2013). "Koh-i-Noor Diamond Will Not Be Returned To India, David Cameron Insists". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2013-07-27.

- ↑ PTI (2013-08-15). "Manmohan first PM outside Nehru-Gandhi clan to hoist flag for 10th time". The Hindu. Retrieved 2014-05-13.

- ↑ India. Ministry of Defence (2005). Sainik samachar. Director of Public Relations, Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ↑ Muslim India. Muslim India. 2004. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ↑ "Red Fort facelift to revive Mughal glory in 10 years : Mail Today Stories, News - India Today". Indiatoday.intoday.in. 2009-06-01. Retrieved 2014-01-03.

- ↑ "CHAPTER-10_revised_jan09.pmd" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-05-13.

- ↑ "CHAPTER-00_revisedfeb09.pmd" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-05-13.

- ↑ Schreitmüller, Karen; Dhamotharan, Mohan (CON); Szerelmy, Beate (CON) (14 February 2012). Baedeker India. Baedeker. p. 253. ISBN 978-3-8297-6622-7. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ↑ Devashish, Dasgupta (2011). Tourism Marketing. Pearson Education India. p. 79. ISBN 978-81-317-3182-6. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ↑ Murthy, Raja (23 February 2012). "Mughal 'paradise' gets tortuous makeover". Asia Times Online (South Asia). Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- 1 2 "Security tightened across Delhi on I-Day eve". Daily News and Analysis. 14 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ↑ "Tight security ensures safe I-Day celebration". The Asian Age. 16 August 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ↑ "Rain Brings Children Cheer, Gives Securitymen a Tough Time". The Hindu. 16 August 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ "Red Fort attack will not affect peace moves". 19 August 2012.

- ↑ "Red Fort terrorist attacks". Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- 1 2 3 Langmead, Donald; Garnaut, Christine (2001). Encyclopedia of Architectural and Engineering Feats. ABC-CLIO. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-57607-112-0.

- ↑ "World Heritage Site – Red Fort, Delhi". Archaeological Survey of India. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ↑ Fanshawe.H.C (1998). Delhi, Past and Present. general introduction (Asian Educational Services). pp. 1–8. ISBN 978-81-206-1318-8. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- ↑ Sharma p.143

- ↑ Mahtab Jahan (2004). "Dilli's gates and windows". MG The Milli Gazette Indian Muslims leading new paper. Retrieved 17 May 2009.

- ↑ "World heritage site". Asi.nic.in.

- 1 2 3 4 "A handbook for travellers in India, Burma, and Ceylon". Archive.org. Retrieved 2014-01-03.

- ↑ "Red Fort Baoli". http://agrasenkibaoli.com. Retrieved 1 August 2015. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ World Heritage Series – RED FORT. Published by Director General, Archaeological Survey of India, New Delhi, 2009. ISBN 978-81-87780-97-7

- ↑ "World Heritage Site – Red Fort, Delhi; Hayat-Bakhsh Garden and Pavilions". Archaeological Survey of India. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Red Fort. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||