La donna è mobile

"La donna è mobile" [la ˈdɔnna ɛ mˈmɔːbile] (The woman is fickle) is the Duke of Mantua's canzone from the beginning of act 3 of Giuseppe Verdi's opera Rigoletto (1851). The canzone is famous as a showcase for tenors. Raffaele Mirate's performance of the bravura aria at the opera's 1851 premiere was hailed as the highlight of the evening. Before the opera's first public performance (in Venice), the song was rehearsed under tight secrecy:[1] a necessary precaution, as "La donna è mobile" proved to be incredibly catchy, and soon after the song's first public performance, every gondolier in Venice was singing it.

As the opera progresses, the reprise of the tune in the following scenes exemplifies a sense of confusion, as Rigoletto realizes that from the sound of the Duke's lively voice coming from within the tavern (offstage), the body in the sack over which he had grimly triumphed, was not that of the Duke after all: Rigoletto had paid Sparafucile, an assassin, to kill the Duke, but Sparafucile had deceived Rigoletto by indiscriminately killing Gilda, Rigoletto's beloved daughter, instead. The song is an irony, as no character in the opera presents traits associated with rationality; every character may be considered callous and mobile ("inconstant").

The music

|

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

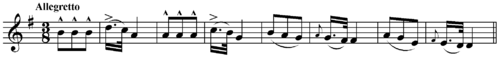

The almost comical-sounding theme of "La donna è mobile" is introduced immediately, and runs as illustrated (transposed from the original key of B major). The theme is repeated several times in the approximately two to three minutes it takes to perform the aria, but with the important—and obvious—omission of the last bar. This has the effect of driving the music forward as it creates the impression of being incomplete and unresolved, which it is, ending not on the tonic or dominant but on the submediant. Once the Duke has finished singing, however, the theme is once again repeated; but this time it includes the last, and conclusive, bar and finally resolving to the tonic. The song is strophic in form with an orchestral ritornello.

Libretto

| Italian | Prosaic translation | Poetic translation |

|---|---|---|

1. La donna è mobile

|

Woman is flighty.

|

Plume in the summerwind

|

References

- ↑ Downes, Olin (1918). The Lure of Music: Depicting the Human Side of Great Composers. Kessinger. p. 38.

External links

- "La donna è mobile" on YouTube; Luciano Pavarotti in the 1992 film by Jean-Pierre Ponnelle

| ||||||||||||||||||