Caracalla

| Caracalla | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Joint 22nd Emperor of the Roman Empire | |||||

| Reign | 198 – 8 April 217 | ||||

| Predecessor | Septimius Severus | ||||

| Successor | Macrinus | ||||

| Co-emperors |

Septimius Severus (198–211) Geta (209–211) | ||||

| Born |

4 April 188 Lugdunum | ||||

| Died |

8 April 217 (aged 29) On the road between Edessa and Carrhae | ||||

| Wife | |||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Severan | ||||

| Father | Septimius Severus | ||||

| Mother | Julia Domna | ||||

| Roman imperial dynasties | |||

| Severan dynasty | |||

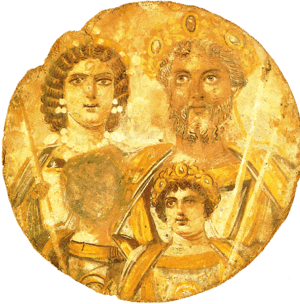

The Severan Tondo | |||

| Chronology | |||

| Septimius Severus | 193–198 | ||

| —with Caracalla | 198–209 | ||

| —with Caracalla and Geta | 209–211 | ||

| Caracalla and Geta | 211–211 | ||

| Caracalla | 211–217 | ||

| Interlude: Macrinus | 217–218 | ||

| Elagabalus | 218–222 | ||

| Alexander Severus | 222–235 | ||

| Dynasty | |||

| Severan dynasty family tree All biographies | |||

| Succession | |||

| Preceded by Year of the Five Emperors |

Followed by Crisis of the Third Century | ||

Caracalla (/ˌkærəˈkælə/) was the popular nickname of Marcus Aurelius Severus Antoninus Augustus[1] (4 April AD 188 – 8 April AD 217), Roman emperor (AD 198–217). The eldest son of Septimius Severus, Caracalla reigned jointly with his father from 198 until Severus' death in 211. For a short time Caracalla then ruled jointly with his younger brother Geta until Caracalla had Geta murdered later in 211. Caracalla is remembered as one of the most notorious and unpleasant of emperors (according to the literate elite) because of the massacres and persecutions he authorized and instigated throughout the Empire.[2][3]

Caracalla's reign was also notable for the Constitutio Antoniniana (also called the Edict of Caracalla or the Antonine Constitution), granting Roman citizenship to all freemen throughout the Roman Empire, which according to the hostile historian Cassius Dio, was done for the purposes of raising tax revenue. This gave all the enfranchised men the two first names of Caracalla "Marcus Aurelius". Caracalla also commissioned a large public bath-house (thermae) project in Rome, and the remains of the Baths of Caracalla are still one of the major tourist attractions of the Italian capital.

Early life

Caracalla, of mixed Berber and Syrian descent, was born Lucius Septimius Bassianus in Lugdunum, Gaul (now Lyon, France), the son of the later Emperor Septimius Severus and Julia Domna. At the age of seven, his name was changed to Marcus Aurelius Septimius Bassianus Antoninus to create a connection to the family of the philosopher emperor Marcus Aurelius. He was later given the nickname Caracalla, which referred to the Gallic hooded tunic he habitually wore and which he made fashionable.

Reign

Murder of brother (211)

His father died in 211 at Eboracum (now York) while on campaign in northern Britain. Caracalla was present and was then proclaimed emperor by the troops along with his brother Publius Septimius Antoninus Geta. Caracalla suspended the campaign in Caledonia and soon ended all military activity, as both brothers wanted to be sole ruler thus making relations between them increasingly hostile. When they tried to rule the Empire jointly they actually considered dividing it in halves, but were persuaded not to do so by their mother.

Then in December 211 at a reconciliation meeting arranged by their mother Julia Domna, Caracalla had Geta assassinated by members of the Praetorian Guard loyal to himself, leading to Geta dying in his mother's arms. Caracalla then persecuted and executed most of Geta's supporters and ordered a damnatio memoriae pronounced by the Senate against his brother's memory.

Geta's image was simply removed from all coinage, paintings and statues, leaving a blank space next to Caracalla's. Among those executed were his former cousin-wife Fulvia Plautilla, his unnamed daughter with Plautilla along with her brother and other members of the family of his former father-in-law Gaius Fulvius Plautianus. Plautianus had already been executed for alleged treachery against emperor Severus in 205.

About the time of his accession he ordered the Roman currency devalued, the silver purity of the denarius was decreased from 56.5% to 51.5%, the actual silver weight dropping from 1.81 grams to 1.66 grams – though the overall weight slightly increased. In 215 he introduced the antoninianus, a "double denarius" weighing 5.1 grams and containing 2.6 grams of silver – a purity of 52%.[4]

In the Roman provinces

In 213, Caracalla went north to the German frontier to deal with the Alamanni tribesmen who had broken through the limes in the Agri Decumates. The Romans defeated the Alamanni in battle near the river Main, but failed to win a decisive victory over them. After a peace agreement was brokered and a large bribe payment given to the invaders, the Senate conferred upon him the empty title of Germanicus Maximus. He was also addressed by the surname Alemannicus at this time.[5] The following year Caracalla traveled to the East, to Syria and Egypt never to return to Rome.

Gibbon in his work describes Caracalla as "the common enemy of mankind". He left the capital in 213, about a year after the murder of Geta, and spent the rest of his reign in the provinces, particularly those of the East. He kept the Senate and other wealthy families in check by forcing them to construct, at their own expense, palaces, theaters, and places of entertainment throughout the periphery. New and heavy taxes were levied against the bulk of the population, with additional fees and confiscations targeted at the wealthiest families.[6]

After Caracalla concluded his campaign against the Alamanni it became evident that he was inordinately preoccupied with the Macedonian general and conqueror, Alexander the Great. He began openly mimicking Alexander in his personal style. In planning his invasion of the Parthian Empire, Caracalla decided to equip 16,000 men (more than three fully staffed legions) of his army as Macedonian style phalanxes, despite the Roman army having made the Phalanx an obsolete tactical formation. This mania for Alexander went so far in that Caracalla visited Alexandria while preparing for his Persian invasion and persecuted philosophers of the Aristotelian school based on a legend that Aristotle had poisoned Alexander. This was a sign that Caracalla was behaving in an erratic manner. But this mania for Alexander, strange as it was, was overshadowed by subsequent events in Alexandria.[7]

When the inhabitants of Alexandria heard Caracalla's claims that he had killed Geta in self-defense, they produced a satire mocking this as well as Caracalla's other pretensions. In 215, Caracalla savagely responded to this insult by slaughtering the deputation of leading citizens who had unsuspectingly assembled before the city to greet his arrival, and then unleashed his troops for several days of looting and plunder in Alexandria. According to historian Cassius Dio 78, 4, 1, over 20,000 people were killed.

Influence of Julia Domna

While Caracalla was mustering and training troops for his planned Persian invasion, Julia remained in Rome, administering the empire. Julia’s growing influence in state affairs was the beginning of a trend of Emperors’ mothers having influence, which continued throughout the Severan dynasty. [8]

Domestic Roman policy

Affiliation with the army

During his reign as emperor, Caracalla raised the annual pay of an average legionary to 675 denarii and lavished many benefits on the army which he both feared and admired, as instructed by his father Septimius Severus who had told both him and his brother Geta on his deathbed always to mind the soldiers and ignore everyone else. Caracalla did manage to win the trust of the military with generous pay raises and popular gestures, like marching on foot among the ordinary soldiers, eating the same food, and even grinding his own flour with them.[9]

With the soldiers, "He forgot even the proper dignity of his rank, encouraging their insolent familiarity," according to Gibbon.[6] "The vigour of the army, instead of being confirmed by the severe discipline of the camps, melted away in the luxury of the cities."

| |

| O: laureate head of Caracalla

ANTONINVS PIVS AVG GERM |

R: Sol holding globe, rising hand |

| silver denarius struck in Rome 216 AD; ref.: RIC 281b, C 359 | |

Seeking to secure his own legacy, Caracalla also commissioned one of Rome's last major architectural achievements, the Baths of Caracalla, the second largest public baths ever built in ancient Rome. The main room of the baths was larger than St. Peter's Basilica, and could easily accommodate over 2,000 Roman citizens at one time. The bath house opened in 216, complete with libraries, private rooms and outdoor tracks. Internally it was lavishly decorated with gold-trimmed marble floors, columns, mosaics and colossal statuary.

Edict of Caracalla (212)

The Constitutio Antoniniana (Latin: "Constitution [or Edict] of Antoninus") (also called Edict of Caracalla or Antonine Constitution) was an edict issued in 212 by Caracalla which declared that all free men in the Roman Empire were to be given full Roman citizenship[10] and all free women in the Empire were given the same rights as Roman women.

Before 212, for the most part only inhabitants of Italia held full Roman citizenship. Colonies of Romans established in other provinces, Romans (or their descendants) living in provinces, the inhabitants of various cities throughout the Empire, and small numbers of local nobles (such as kings of client countries) held full citizenship also. Provincials, on the other hand, were usually non-citizens, although many held the Latin Right.

The Roman Historian Cassius Dio contended that the sole motivation for the edict was a desire to increase state revenue, coupled with the debasement of the currency, needed to pay for the new pay raises and benefits conferred on the military.[11] At the time aliens did not have to pay most taxes that were required of citizens, so although nominally Caracalla was elevating their legal status, he was more importantly expanding the Roman tax base. The effect of this was to remove the distinction that citizenship had held since the foundation of Rome and as such the act had a profound effect upon the fabric of Roman society.[12]

War with Parthia

Caracalla pursued a series of aggressive campaigns in the east, designed to bring more territory under direct Roman control. He attempted to find pretexts for invading Parthia, culminating in a proposal of marriage between himself and the daughter of king Artabanus V of Parthia. According to the historian Herodian, in 216, Caracalla tricked the Parthians into believing that he was sincere in his marriage and peace proposal, but then attacked the bride and guests at the wedding celebrations. Artabanus barely escaped. His daughter and many high ranking Parthians were massacred. The thereafter ongoing conflict and skirmishes became known as the Parthian war of Caracalla.[13]

Assassination (217)

While travelling from Edessa to continue the war with Parthia, he was assassinated while urinating at a roadside near Carrhae (now Harran in southern Turkey) on 8 April 217 (4 days after his 29th birthday), by Julius Martialis, an officer of his personal bodyguard. Herodian says that Martialis's brother had been executed a few days earlier by Caracalla on an unproven charge; Cassius Dio, on the other hand, says that Martialis was resentful at not being promoted to the rank of centurion. The escort of the emperor gave him privacy to relieve himself, and Martialis then ran forward and killed Caracalla with a single sword stroke. While attempting to flee, the bold assassin was then quickly dispatched by a Scythian archer of the Imperial Guard.[6]

Caracalla was succeeded by his Praetorian Guard Prefect, Macrinus, who (according to Herodian) was most probably responsible for having the emperor assassinated.

His nickname

According to Aurelius Victor in his Epitome de Caesaribus, the agnomen "Caracalla" refers to a Gallic cloak that Caracalla adopted as a personal fashion, which spread to his army and his court.[14] Cassius Dio[15] and the Historia Augusta[16] agree that his nickname was derived from his cloak, but do not mention its country of origin.

Portrait

His official portraiture as sole emperor marks a break with the detached images of the philosopher–emperors who preceded him: his close-cropped haircut is that of a soldier, his pugnacious scowl a realistic and threatening presence. This rugged soldier–emperor iconic archetype was adopted by most of the following emperors who depended on the support of the troops to rule, such as Maximinus Thrax.[17]

Herodian describes Caracalla as not tall, but robust. He preferred Northern European clothing, caracalla being the name of the short Gaulish cloak that he made fashionable, and often wore a blond wig.[18] Vgl. Cassius Dio 79 (78),9,3: Cassius Dio mentions that the emperor liked to show a "wild" facial expression.[19]

We can see how he wanted to be portrayed to his people through many surviving busts and coins. Images of the young Caracalla cannot be well distinguished from his younger brother Geta. On the coins the older brother Caracalla was however shown with laureate since becoming Augustus in 197 while Geta is bareheaded until himself becoming Augustus in 209.[20] Especially between 209 and their father's death in February 211 both brothers are shown as mature young men, ready to take over the empire. Between the death of the father and the assassination of Geta towards the end of 211 Caracalla's portrait remains static with a short full beard, while Geta develops a long beard with hair strains like his father, a strong indicator for the effort to be seen as the "true" successor to their father. The brutal murder of Geta made this claim obsolete of course.[20]

Legendary king of Britain

Geoffrey of Monmouth's legendary History of the Kings of Britain makes Caracalla a king of Britain, referring to him by his actual name "Bassianus", rather than the nickname Caracalla. In the story, after Severus's death the Romans wanted to make Geta king of Britain, but the Britons preferred Bassianus because he had a British mother. The two brothers fought a battle in which Geta was killed and Bassianus succeeded to the throne. He ruled until he was betrayed by his Pictish allies and overthrown by Carausius, who, according to Geoffrey, was a Briton, rather than the historically much later Menapian Gaul that he actually was.[21]

Severan family tree

| Severan family tree | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- ↑

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Caracalla". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Caracalla". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - ↑ Hurley, P. (2011). Life of Caracalla at Ancient History Encyclopedia

- ↑ "Caracalla" A Dictionary of British History. Ed. John Cannon. Oxford University Press, 2001. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press.

"Caracalla" World Encyclopedia. Philip's, 2005. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. - ↑ Tulane University "Roman Currency of the Principate"

- ↑ Everyman's Smaller Classical Dictionary, 1910, p. 31

- 1 2 3 Gibbon, Edward, The Decline And Fall Of The Roman Empire, Vol. 1. Chapter 6.

- ↑ Brauer, G (1967), “The Decadent Emperors, Power & Depravity in Third-Century Rome”, p.75

- ↑ Grant, M (1996), “The Severans, the Changed Roman Empire”, p. 46

- ↑ Caracalla

- ↑ "Late Antinquity" by Richard Lim in The Edinburgh Companion to Ancient Greece and Rome. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010, p. 114.

- ↑ http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Cassius_Dio/78*.html

- ↑ Leithart, P. (2010), Defending Constantine: The Twilight of an Empire and the Dawn of Christendom, p. 35

- ↑ Herodian's Roman History, chapter 4.11: Caracalla's Parthian War, translated by Edward C. Echols (Herodian of Antioch's History of the Roman Empire, 1961 Berkeley and Los Angeles), online at Livius.org

- ↑ Aurelius Victor, Epitome de Caesaribus 21 (translation). For information on the caracallus garment, see William Smith Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities: "Caracalla"

- ↑ Cassius Dio, Roman History 79.3

- ↑ Historia Augusta: Caracalla 9.7, Septimius Severus 21.11

- ↑ Metropolitan Museum of Art: Portrait head of the Emperor Caracalla". acc. no. 40.11.1a

- ↑ Herodian 4,7 and 4,9,3.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 78 (77),11,1.

- 1 2 Andreas Pangerl: Porträttypen des Caracalla und des Geta auf Römischen Reichsprägungen - Definition eines neuen Caesartyps des Caracalla und eines neuen Augustustyps des Geta; Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt des RGZM Mainz 43, 2013, 1, 99–116

- ↑ Geoffrey of Monmouth, Historia Regum Britanniae 5.2–3

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Caracalla. |

External links

- Life of Caracalla (Historia Augusta at LacusCurtius: Latin text and English translation)

|