Tartaric acid

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

2,3-dihydroxybutanedioic acid | |

| Other names

2,3-dihydroxysuccinic acid threaric acid racemic acid uvic acid paratartaric acid | |

| Identifiers | |

| 526-83-0 | |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:15674 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL333714 ChEMBL1200861 |

| ChemSpider | 852 |

| DrugBank | DB01694 |

| Jmol interactive 3D | Image |

| KEGG | C00898 |

| MeSH | tartaric+acid |

| PubChem | 875 |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C4H6O6 (Basic formula) HO2CCH(OH)CH(OH)CO2H (Structural formula) | |

| Molar mass | 150.087 g/mol |

| Appearance | white powder |

| Density | 1.79 g/mL (H2O) |

| Melting point | 171 to 174 °C (340 to 345 °F; 444 to 447 K) (L or D-tartaric; pure) 206 °C (DL, racemic) 165–166 °C ("meso-anhydrous") 146–148 °C (meso-hydrous)[2] |

| 1.33 kg/L (L or D-tartaric) 0.21 kg/L (DL, racemic) | |

| Acidity (pKa) | L(+) 25 °C : pKa1= 2.89 pKa2= 4.40 meso 25 °C: pKa1= 3.22 pKa2= 4.85 |

| Hazards | |

| EU classification (DSD) |

Irritant(Xi) |

| R-phrases | R36 |

| Related compounds | |

| Other cations |

Monosodium tartrate Disodium tartrate Monopotassium tartrate Dipotassium tartrate |

| Related carboxylic acids |

Butyric acid Succinic acid Dimercaptosuccinic acid Malic acid Maleic acid Fumaric acid |

| Related compounds |

2,3-Butanediol Cichoric acid |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

Tartaric acid is a white crystalline organic acid that occurs naturally in many plants, most notably in grapes. Its salt, potassium bitartrate, commonly known as cream of tartar, develops naturally in the process of winemaking. It is commonly mixed with sodium bicarbonate and is sold as baking powder used as a leavening agent in food preparation. The acid itself is added to foods as an antioxidant and to impart its distinctive sour taste.

Tartaric is an alpha-hydroxy-carboxylic acid, is diprotic and aldaric in acid characteristics, and is a dihydroxyl derivative of succinic acid.

History

Tartaric acid was first isolated from potassium bitartrate circa 800 AD, by the alchemist Jābir ibn Hayyān.[4] The modern process was developed in 1769 by the Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele.

Tartaric acid played an important role in the discovery of chemical chirality. This property of tartaric acid was first observed in 1832 by Jean Baptiste Biot, who observed its ability to rotate polarized light. Louis Pasteur continued this research in 1847 by investigating the shapes of ammonium sodium tartrate crystals, which he found to be chiral. By manually sorting the differently shaped crystals under magnification, Pasteur was the first to produce a pure sample of levotartaric acid.[5][6][7][8]

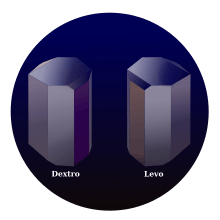

Stereochemistry

Naturally occurring tartaric acid is chiral, meaning it has molecules that are not superimposable on their mirror images. It is a useful raw material in organic chemistry for the synthesis of other chiral molecules. The naturally occurring form of the acid is L-(+)-tartaric acid or levotartaric acid. The mirror-image (enantiomeric) form, dextrotartaric acid or D-(-)-tartaric acid, and the achiral form, mesotartaric acid, can be made artificially. The dextro and levo prefixes are not related to the D/L configuration (which is derived rather indirectly[9] from their structural relation to D- or L-glyceraldehyde), but to the orientation of the optical rotation, (+) = dextrorotatory, (−) = levorotatory. Sometimes, instead of capital letters, small italic d and l are used. They are abbreviations of dextro- and levo- and, nowadays, should not be used. Levotartaric and dextrotartaric acid are enantiomers, mesotartaric acid is a diastereomer of both of them.[10][11]

A rarely occurring, optically inactive form of tartaric acid, DL-tartaric acid is a 1:1 mixture of the levo and dextro forms. It is distinct from mesotartaric acid and was called racemic acid (from Latin racemus – "a bunch of grapes"). The word racemic later changed its meaning, becoming a general term for 1:1 enantiomeric mixtures – racemates.

Tartaric acid is used to prevent copper(II) ions from reacting with the hydroxide ions present in the preparation of copper(I) oxide. Copper(I) oxide is a reddish-brown solid, and is produced by the reduction of a Cu(II) salt with an aldehyde, in an alkaline solution.

| levotartaric acid (L-(+)-tartaric acid) | dextrotartaric acid (D-(-)-tartaric acid) | mesotartaric acid |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

DL-tartaric acid (racemic acid) | ||

| Forms of tartaric acid | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common name | tartaric acid | Dextrotartaric acid | Levotartaric acid | mesotartaric acid | racemic acid | |

| Synonyms | D-(S,S)-(−)-tartaric acid unnatural isomer |

L-(R,R)-(+)-tartaric acid natural isomer |

(2R,3S)-tartaric acid | DL-(S,S/R,R)-(±)-tartaric acid | ||

| PubChem | CID 875 from PubChem | CID 439655 from PubChem | CID 444305 from PubChem | CID 78956 from PubChem | CID 5851 from PubChem | |

| EINECS number | ||||||

| CAS number | 526-83-0 | 147-71-7 | 87-69-4 | 147-73-9 | 133-37-9 | |

Production

L-(+)-tartaric acid

The L-(+)-tartaric acid isomer of tartaric acid is industrially produced in the largest amounts. It is obtained from naturally occurring component of lees, a solid byproduct of fermentations. The former byproducts mostly consist of potassium bitartrate (KHC4H4O6). This potassium salt is converted to calcium tartrate (CaC4H4O6) upon treatment with milk of lime (Ca(OH)2):[12]

- KO2CCH(OH)CH(OH)CO2H + Ca(OH)2 → Ca(O2CCH(OH)CH(OH)CO2) + KOH + H2O

In practice, higher yields of calcium tartrate are obtained with the addition of calcium chloride. Calcium tartrate is then converted to tartaric acid by treating the salt with aqueous sulfuric acid. This process yields free L-(+)-tartaric acid:

- Ca(O2CCH(OH)CH(OH)CO2) + H2SO4 → HO2CCH(OH)CH(OH)CO2H + CaSO4

Racemic tartaric acid

Racemic tartaric acid can be prepared in a multistep reaction from maleic acid. In the first step, the maleic acid is epoxidized by hydrogen peroxide using potassium tungstate as a catalyst.[12]

- HO2CC2H4CO2H + H2O2 → OC2H2(CO2H) 2

In the next step, the epoxide is hydrolyzed to form racemic tartaric acid.

- OC2H2(CO2H)2 + H2O → (HOCH)2(CO2H)2

Meso-tartaric acid

Meso-tartaric acid is formed via thermal isomerization. Dextro-tartaric acid is heated in water at 165 °C for about 2 days. Meso-tartaric acid can also be prepared from dibromosuccinic acid using silver hydroxide.[13]

- HO2CCHBrCHBrCO2H + 2 AgOH → HO2CCH(OH)CH(OH)CO2H + 2 AgBr

Meso-tartaric acid can be separated from the racemic acid by crystallization, the racemate being less soluble.

Reactivity

L-(+)-tartaric acid, can participate in several reactions. As shown the reaction scheme below, dihydroxymaleic acid is produced upon treatment of L-(+)-tartaric acid with hydrogen peroxide in the presence of a ferrous salt.

- HO2CCH(OH)CH(OH)CO2H + H2O2 → HO2CC(OH)C(OH)CO2H + 2 H2O

Dihydroxymaleic acid can then be oxidized to tartronic acid with nitric acid.[14]

Derivatives

Important derivatives of tartaric acid include its salts, cream of tartar (potassium bitartrate), Rochelle salt (potassium sodium tartrate, a mild laxative), and tartar emetic (antimony potassium tartrate).[15][16][17] Diisopropyl tartrate is used as a catalyst in asymmetric synthesis.

Tartaric acid is a muscle toxin, which works by inhibiting the production of malic acid, and in high doses causes paralysis and death.[18] The median lethal dose (LD50) is about 7.5 grams/kg for a human, 5.3 grams/kg for rabbits, and 4.4 grams/kg for mice.[19] Given this figure, it would take over 500 g (18 oz) to kill a person weighing 70 kg (150 lb), so it may be safely included in many foods, especially sour-tasting sweets. As a food additive, tartaric acid is used as an antioxidant with E number E334; tartrates are other additives serving as antioxidants or emulsifiers.

When cream of tartar is added to water, a suspension results which serves to clean copper coins very well, as the tartrate solution can dissolve the layer of copper(II) oxide present on the surface of the coin. The resulting copper(II)-tartrate complex is easily soluble in water.

Tartaric acid in wine

Tartaric acid may be most immediately recognizable to wine drinkers as the source of "wine diamonds", the small potassium bitartrate crystals that sometimes form spontaneously on the cork or bottom of the bottle. These "tartrates" are harmless, despite sometimes being mistaken for broken glass, and are prevented in many wines through cold stabilization, although not always preferred since it can change the wine's profile. The tartrates remaining on the inside of aging barrels were at one time a major industrial source of potassium bitartrate.

Tartaric acid plays an important role chemically, lowering the pH of fermenting "must" to a level where many undesirable spoilage bacteria cannot live, and acting as a preservative after fermentation. In the mouth, tartaric acid provides some of the tartness in the wine, although citric and malic acids also play a role.

Applications

Tartaric acid and its derivatives have a plethora of uses in the field of pharmaceuticals. For example, tartaric acid has been used in the production of effervescent salts, in combination with citric acid, in order to improve the taste of oral medications.[14] The potassium antimonyl derivative of the acid known as tartar emetic is included, in small doses, in cough syrup as an expectorant.

Tartaric acid also has several applications for industrial use. The acid has been observed to chelate metal ions such as calcium and magnesium. Therefore, the acid has served in the farming and metal industries as a chelating agent for complexing micronutrients in soil fertilizer and for cleaning metal surfaces consisting of aluminium, copper, iron, and alloys of these metals, respectively.[12]

References

- ↑ Tartaric Acid – Compound Summary, PubChem.

- ↑ Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- ↑ Dawson, R.M.C. et al., Data for Biochemical Research, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1959.

- ↑ Lisa Solieri, Paolo Giudici (2009). Vinegars of the World. Springer. p. 29. ISBN 88-470-0865-4.

- ↑ L. Pasteur (1848) "Mémoire sur la relation qui peut exister entre la forme cristalline et la composition chimique, et sur la cause de la polarisation rotatoire" (Memoir on the relationship which can exist between crystalline form and chemical composition, and on the cause of rotary polarization)," Comptes rendus de l'Académie des sciences (Paris), vol. 26, pp. 535–538.

- ↑ L. Pasteur (1848) "Sur les relations qui peuvent exister entre la forme cristalline, la composition chimique et le sens de la polarisation rotatoire" (On the relations that can exist between crystalline form, and chemical composition, and the sense of rotary polarization), Annales de Chimie et de Physique, 3rd series, vol. 24, no. 6, pages 442–459.

- ↑ George B. Kauffman and Robin D. Myers (1998). "Pasteur's resolution of racemic acid: A sesquicentennial retrospect and a new translation" (PDF). The Chemical Educator 3 (6): 1–4. doi:10.1007/s00897980257a.

- ↑ H. D. Flack (2009). "Louis Pasteur's discovery of molecular chirality and spontaneous resolution in 1848, together with a complete review of his crystallographic and chemical work" (PDF). Acta Crystallographica A 65 (5): 371–389. doi:10.1107/S0108767309024088. PMID 19687573.

- ↑ J. M. McBride's Yale lecture on history of stereochemistry of tartaric acid, the D/L and R/S systems

- ↑ various (2007-07-23). Organic Chemistry. Global Media. p. 65. ISBN 978-81-89940-76-8. Retrieved 2010-06-05.

- ↑ "(WO/2008/022994) Use of azabicyclo hexane derivatives".

- 1 2 3 J.-M. Kassaian "Tartaric acid" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry; VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2002, 35, 671-678. doi:10.1002/14356007.a26_163

- ↑ Augustus Price West. Experimental Organic Chemistry. World Book Company: New York, 1920, 232-237.

- 1 2 Blair, G. T.; DeFraties, J. J. (2000). "Hydroxy Dicarboxylic Acids". Kirk Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. pp. 1–19. doi:10.1002/0471238961.0825041802120109.a01.

- ↑ Zalkin, Allan; Templeton, David H.; Ueki, Tatzuo (1973). "Crystal structure of l-tris(1,10-phenathroline)iron(II) bis(antimony(III) d-tartrate) octahydrate". Inorganic Chemistry 12 (7): 1641–1646. doi:10.1021/ic50125a033.

- ↑ Haq, I; Khan, C (1982). "Hazards of a traditional eye-cosmetic--SURMA". JPMA. the Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association 32 (1): 7–8. PMID 6804665.

- ↑ McCallum, RI (1977). "President's address. Observations upon antimony". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 70 (11): 756–63. PMC 1543508. PMID 341167.

- ↑ Alfred Swaine Taylor, Edward Hartshorne (1861). Medical jurisprudence. Blanchard and Lea. p. 61.

- ↑ Joseph A. Maga, Anthony T. Tu (1995). Food additive toxicology. CRC Press. pp. 137–138. ISBN 0-8247-9245-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tartaric acid. |

|