Kurgan hypothesis

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

Archaeology Steppe Europe Steppe Europe South-Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies

|

|

Religion and mythology |

The Kurgan hypothesis (also known as the Kurgan theory or Kurgan model) is the most widely accepted proposal of several solutions to explain the origins and spread of the Indo-European languages.[note 1] It postulates that the people of an archaeological "Kurgan culture" in the Pontic steppe were the most likely speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language. The term is derived from kurgan (курган), a Turkic loanword in Russian for a tumulus or burial mound.

The Kurgan hypothesis was first formulated in the 1950s by Marija Gimbutas, who used the term to group various cultures, including the Yamna, or Pit Grave, culture and its predecessors. David Anthony instead uses the core Yamna Culture and its relationship with other cultures as a point of reference.

Marija Gimbutas defined the "Kurgan culture" as composed of four successive periods, with the earliest (Kurgan I) including the Samara and Seroglazovo cultures of the Dnieper/Volga region in the Copper Age (early 4th millennium BC). The people of these cultures were nomadic pastoralists, who, according to the model, by the early 3rd millennium BC had expanded throughout the Pontic-Caspian steppe and into Eastern Europe.[3]

Overview

Arguments for the identification of the Proto-Indo-Europeans as steppe nomads from the Pontic-Caspian region had already been made in the 19th century by Theodor Benfey and pre-eminently Otto Schrader.[4][5] In his standard work about PIE and to a greater extent in a later abbreviated version, Karl Brugmann took the view that the Urheimat could not be identified exactly at that time, but he tended toward Schrader’s view.[6][7] Later on, some scholars favoured the view of a Northern European origin. The view of a Pontic origin was still strongly favoured, e.g., by the archaeologist Ernst Wahle.[8] One of Wahle's students was Jonas Puzinas, who in turn was one of Gimbutas’ teachers. Gimbutas, who acknowledges Schrader as a precursor,[9] was able to marshal a wealth of archaeological evidence from the territory of the Soviet Union (and other countries then belonging to the eastern bloc) not readily available to scholars from western countries,[10] enabling her to achieve a fuller picture of prehistoric Europe.

When it was first proposed in 1956, in The Prehistory of Eastern Europe, Part 1, Marija Gimbutas's contribution to the search for Indo-European origins was an interdisciplinary synthesis of archaeology and linguistics. The Kurgan model of Indo-European origins identifies the Pontic-Caspian steppe as the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) Urheimat, and a variety of late PIE dialects are assumed to have been spoken across the region. According to this model, the Kurgan culture gradually expanded until it encompassed the entire Pontic-Caspian steppe, Kurgan IV being identified with the Pit Grave culture of around 3000 BC.

The mobility of the Kurgan culture facilitated its expansion over the entire Pit Grave region, and is attributed to the domestication of the horse and later the use of early chariots.[note 2] The first strong archaeological evidence for the domestication of the horse comes from the Sredny Stog culture north of the Azov Sea in Ukraine, and would correspond to an early PIE or pre-PIE nucleus of the 5th millennium BC.[note 2]

Subsequent expansion beyond the steppes led to hybrid, or in Gimbutas's terms "kurganized" cultures, such as the Globular Amphora culture to the west. From these kurganized cultures came the immigration of Proto-Greeks to the Balkans and the nomadic Indo-Iranian cultures to the east around 2500 BC.

Kurgan culture

Cultural horizon

Gimbutas defined and introduced the term "Kurgan culture" in 1956 with the intention of introducing a "broader term" that would combine Sredny Stog II, Pit-Grave and Corded ware horizons (spanning the 4th to 3rd millennia in much of Eastern and Northern Europe).[note 3] The model of a "Kurgan culture" treats the various cultures of the Copper Age to Early Bronze Age (5th to 3rd millennia BC) Pontic-Caspian steppe to justify the identification as a single archaeological culture or cultural horizon, based on similarities among them. The eponymous construction of kurgans is only one among several factors. As always in the grouping of archaeological cultures, the dividing line between one culture and the next cannot be drawn with any accuracy and will be open to debate.

Cultures that Gimbutas considered as part of the "Kurgan culture":

- Bug-Dniester (6th millennium)

- Samara (5th millennium)

- Kvalynsk (5th millennium)

- Sredny Stog (mid-5th to mid-4th millennia)

- Dnieper-Donets (5th to 4th millennia)

- Usatovo culture (late 4th millennium)

- Maikop-Dereivka (mid-4th to mid-3rd millennia)

- Yamna (Pit Grave): This is itself a varied cultural horizon, spanning the entire Pontic-Caspian steppe from the mid-4th to the 3rd millennium.

Yamna culture

David Anthony considers the term "Kurgan culture" so lacking in precision as to be useless, instead using the core Yamna culture and its relationship with other cultures as a point of reference.[11] He points out that

The Kurgan culture was so broadly defined that almost any culture with burial mounds, or even (like the Baden culture) without them could be included.[11]

He does not include the Maykop culture among those that he considers to be IE-speaking, presuming instead that they spoke a Caucasian language.[12]

Stages of culture and expansion

Gimbutas' original suggestion identifies four successive stages of the Kurgan culture:

- Kurgan I, Dnieper/Volga region, earlier half of the 4th millennium BC. Apparently evolving from cultures of the Volga basin, subgroups include the Samara and Seroglazovo cultures.

- Kurgan II–III, latter half of the 4th millennium BC. Includes the Sredny Stog culture and the Maykop culture of the northern Caucasus. Stone circles, anthropomorphic stone stelae of deities.

- Kurgan IV or Pit Grave culture, first half of the 3rd millennium BC, encompassing the entire steppe region from the Ural to Romania.

There were three successive proposed "waves" of expansion:

- Wave 1, predating Kurgan I, expansion from the lower Volga to the Dnieper, leading to coexistence of Kurgan I and the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture. Repercussions of the migrations extend as far as the Balkans and along the Danube to the Vinča culture in Serbia and Lengyel culture in Hungary.

- Wave 2, mid 4th millennium BC, originating in the Maykop culture and resulting in advances of "kurganized" hybrid cultures into northern Europe around 3000 BC (Globular Amphora culture, Baden culture, and ultimately Corded Ware culture). According to Gimbutas this corresponds to the first intrusion of Indo-European languages into western and northern Europe.

- Wave 3, 3000–2800 BC, expansion of the Pit Grave culture beyond the steppes, with the appearance of the characteristic pit graves as far as the areas of modern Romania, Bulgaria, eastern Hungary and Georgia, coincident with the end of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture and Trialeti culture in Georgia (c.2750 BC).

Timeline

- 4500–4000: Early PIE. Sredny Stog, Dnieper-Donets and Samara cultures, domestication of the horse (Wave 1).

- 4000–3500: The Pit Grave culture (a.k.a. Yamna culture), the prototypical kurgan builders, emerges in the steppe, and the Maykop culture in the northern Caucasus. Indo-Hittite models postulate the separation of Proto-Anatolian before this time.

- 3500–3000: Middle PIE. The Pit Grave culture is at its peak, representing the classical reconstructed Proto-Indo-European society with stone idols, predominantly practicing animal husbandry in permanent settlements protected by hillforts, subsisting on agriculture, and fishing along rivers. Contact of the Pit Grave culture with late Neolithic Europe cultures results in the "kurganized" Globular Amphora and Baden cultures (Wave 2). The Maykop culture shows the earliest evidence of the beginning Bronze Age, and Bronze weapons and artifacts are introduced to Pit Grave territory. Probable early Satemization.

- 3000–2500: Late PIE. The Pit Grave culture extends over the entire Pontic steppe (Wave 3). The Corded Ware culture extends from the Rhine to the Volga, corresponding to the latest phase of Indo-European unity, the vast "kurganized" area disintegrating into various independent languages and cultures, still in loose contact enabling the spread of technology and early loans between the groups, except for the Anatolian and Tocharian branches, which are already isolated from these processes. The Centum-Satem break is probably complete, but the phonetic trends of Satemization remain active.

Genetics

As used by Gimbutas, the term "kurganized" implied that the culture could have been spread by no more than small bands who imposed themselves on local people as an elite. This idea of the PIE language and its daughter-languages diffusing east and west without mass movement proved popular with archaeologists in the 1970s (the pots-not-people paradigm).[13] At the time, no genetic evidence was available; the rapidly developing field of archaeogenetics and genetic genealogy since the late 1990s has not only confirmed a migratory pattern out of the Pontic Steppe at the relevant time, it also suggests the possibility that the population movement involved was more substantial than anticipated.

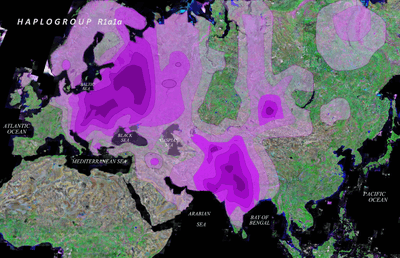

Geneticists have noted the correlation of a specific haplogroup, R1a1a, defined by the M17 (SNP marker) of the Y chromosome, and speakers of Indo-European languages in Europe and Asia. The connection between Y-DNA R-M17 and the spread of Indo-European languages was first proposed by Zerjal and colleagues in 1999.[14] and subsequently supported by other authors.[15] Spencer Wells deduced from this correlation that R1a1a arose on the Pontic-Caspian steppe.[16]

Subsequent studies on ancient DNA tested the hypothesis. Skeletons from the Andronovo culture horizon (strongly supposed to be culturally Indo-Iranian) of south Siberia were tested for DNA. Of the ten males, nine carried Y-DNA R1a1a (M17). Fairly close matches were found between the ancient DNA STR haplotypes and those in living persons in both eastern Europe and Siberia.[17] Mummies in the Tarim Basin also proved to carry R1a1a and were presumed to be ancestors of Tocharian speakers.[18]

A study published in 2012 states that "R1a1a7-M458 was absent in Afghanistan, suggesting that R1a1a-M17 does not support, as previously thought, expansions from the Pontic Steppe, bringing the Indo-European languages to Central Asia and India."[19] However, this study does not in any way conflict with the hypothesis of expansions from the Pontic Steppe, since the study does not take into account the early wave of the Indo-European speaking people. Even today the R1a1a7-M458 are very rare, almost absent, in the area of the proposed Indo-European origins between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea; the R1a1a7-M458 marker first started in Poland 10,000 years ago (KYA), and arrived in the western fringes of the Pontic steppe 5,000 years ago and the eastern fringes only 2,500 years ago, while the first Indo-European wave (4500–4000 BC Early PIE) began up to 4,000 years before this.

The DNA testing of remains from kurgans also indicated a high prevalence of people with characteristics such as blue (or green) eyes, fair skin and light hair, implying an origin close to Europe for this population.[20]

Several 4,600-year-old human remains at a Corded Ware site in Eulau, Germany, were also found to belong to haplogroup R1a1a.[21]

In 2015 researchers reported on a DNA analysis of 94 ancient skeletons mostly 8,000–3,000 years old from Europe and Russia. They found that there was a major migration of Yamna culture people who entered Europe from the North Pontic steppe about 4,500 years ago and whose DNA spread widely throughout Europe. They concluded that this massive influx of Yamnaya herders provide support for the origin of at least some of the Indo-European languages in Europe.[22] They also found that the about 75% of the DNA of Late Neolithic Corded Ware skeletons in Germany were the same as the Yamnaya DNA.

Further expansion during the Bronze Age

The Kurgan hypothesis describes the initial spread of Proto-Indo-European during the 5th and 4th millennia BC.[23] The question of further Indo-Europeanization of Central and Western Europe, Central Asia and Northern India during the Bronze Age is beyond its scope, far more uncertain than the events of the Copper Age, and subject to some controversy.

Anatolia

The Anatolian languages are a family of extinct Indo-European languages that were spoken in Asia Minor (ancient Anatolia), the best attested of them being the Hittite language. The Maykop culture (also spelled Maikop), c. 3700 BC–3000 BC,[24] was a major Bronze Age archaeological culture in the Western Caucasus region of Southern Russia. The Hittites were an ancient Anatolian people who established an empire at Hattusa in north-central Anatolia around 1600 BC. This empire reached its height during the mid-14th century BC under Suppiluliuma I, when it encompassed an area that included most of Asia Minor as well as parts of the northern Levant and Upper Mesopotamia. After c. 1180 BC, the empire came to an end during the Bronze Age collapse, splintering into several independent "Neo-Hittite" city-states, some of which survived until the 8th century BC.

Europe

The European Funnelbeaker and Corded Ware cultures have been described as showing intrusive elements linked to Indo-Europeanization, but recent archaeological studies have described them in terms of local continuity, which has led some archaeologists to declare the Kurgan hypothesis obsolete.[25] However, it is generally held unrealistic to believe that a proto-historic people can be assigned to any particular group on the basis of archaeological material alone.[26]

The Corded Ware culture has always been important in locating Indo-European origins. The German archaeologist Alexander Häusler was an important proponent of archaeologists who searched for homeland evidence here. He sharply criticised Gimbutas' concept of "a" Kurgan culture that mixes several distinct cultures like the pit-grave culture. Häusler's criticism mostly stemmed from a distinctive lack of archaeological evidence from what was then the East Bloc until 1950, after which plenty of evidence for Gimbutas's Kurgan hypothesis continued to be discovered for decades.[27] He was unable to link Corded Ware to the Indo-Europeans of the Balkans, Greece or Anatolia, or to the Indo-Europeans in Asia. Nevertheless, establishing the correct relationship between the Corded Ware and Pontic-Caspian regions is still considered essential to solving the entire homeland problem.[28]

Central Asia

From the Pontic Steppe Indo-European people moved east, where they founded the Sintashta culture and the Andronovo culture. The Sintashta culture, also known as the Sintashta-Petrovka culture[29] or Sintashta-Arkaim culture,[30] is a Bronze Age archaeological culture of the northern Eurasian steppe on the borders of Eastern Europe and Central Asia, dated to the period 2100–1800 BC.[31] The Andronovo culture is a collection of similar local Bronze Age Indo-Iranian cultures that flourished c. 1800–1400 BC in western Siberia and the west Asiatic steppe. It is probably better termed an archaeological complex or archaeological horizon. The name derives from the village of Andronovo (55°53′N 55°42′E / 55.883°N 55.700°E), where in 1914, several graves were discovered, with skeletons in crouched positions, buried with richly decorated pottery.

From these cultures further migrations went further east, to found the Afanasevo culture, and the Tocharian languages formerly spoken by Tocharian peoples in oases on the northern edge of the Tarim Basin (now part of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China). The Indo-Iranian branch went south, forming the Iranian people and the Indo-Aryan migration into India. Closely related to the Indo-Aryans were the Mitanni, who founded a kingdom in the Middle East.

Revisions

Invasionist vs. diffusionist scenarios

Gimbutas believed that the expansions of the Kurgan culture were a series of essentially hostile, military incursions where a new warrior culture imposed itself on the peaceful, matriarchal cultures of "Old Europe", replacing it with a patriarchal warrior society,[32] a process visible in the appearance of fortified settlements and hillforts and the graves of warrior-chieftains:

The process of Indo-Europeanization was a cultural, not a physical, transformation. It must be understood as a military victory in terms of successfully imposing a new administrative system, language, and religion upon the indigenous groups.[33]

In her later life, Gimbutas increasingly emphasized the violent nature of this transition from the Mediterranean cult of the Mother Goddess to a patriarchal society and the worship of the warlike Thunderer (Zeus, Dyaus), to a point of essentially formulating a feminist archaeology. Many scholars who accept the general scenario of Indo-European migrations maintain that the transition was probably much more gradual and peaceful than suggested by Gimbutas. The migrations were certainly not a sudden, concerted military operation, but the expansion of disconnected tribes and cultures, spanning many generations. To what degree the indigenous cultures were peacefully amalgamated or violently displaced remains a matter of controversy among supporters of the Kurgan hypothesis.

J. P. Mallory (in 1989) accepted the Kurgan hypothesis as the de facto standard theory of Indo-European origins, but he recognized valid criticism of Gimbutas' radical scenario of military invasion:

One might at first imagine that the economy of argument involved with the Kurgan solution should oblige us to accept it outright. But critics do exist and their objections can be summarized quite simply – almost all of the arguments for invasion and cultural transformations are far better explained without reference to Kurgan expansions, and most of the evidence so far presented is either totally contradicted by other evidence or is the result of gross misinterpretation of the cultural history of Eastern, Central, and Northern Europe.[34]

Kortlandt's proposal

Frederik Kortlandt in 1989 proposed a revision of the Kurgan model.[35] He states the main objection which can be raised against Gimbutas' scheme (e.g., 1985: 198) is that it starts from the archaeological evidence and looks for a linguistic interpretation. Starting from the linguistic evidence and trying to fit the pieces into a coherent whole, he arrives at the following picture: The territory of the Sredny Stog culture in the eastern Ukraine he calls the most convincing candidate for the original Indo-European homeland. The Indo-Europeans who remained after the migrations to the west, east and south (as described by Mallory 1989) became speakers of Balto-Slavic, while the speakers of the other satem languages would have to be assigned to the Pit Grave horizon, and the western Indo-Europeans to the Corded Ware horizon. Returning to the Balts and the Slavs, their ancestors should be correlated to the Middle Dnieper culture. Then, following Mallory (197f) and assuming the origin of this culture to be sought in the Sredny Stog, Yamnaya and Late Tripolye cultures, he proposes the course of these events corresponds with the development of a satem language which was drawn into the western Indo-European sphere of influence.

Criticisms

Occurrence of horse riding in Europe

Renfrew (1999: 268) holds that mounted warriors appear in Europe only as late as 1000 BC and these could in no case have been "Gimbutas's Kurgan warriors" predating the facts by some 2,000 years. Mallory (1989, p. 136) enumerates linguistic evidence pointing to PIE period employment of horses in paired draught, something that would not have been possible before the invention of the spoked wheel and chariot, normally dated after about 2500 BC.[36]

In fact, currently, the earliest well-dated depiction of a wheeled vehicle in Europe is on the Bronocice pot (c. 3500 BC); the oldest securely dated real wheel-axle combination is the Ljubljana Marshes Wheel (c. 3150).

According to Krell (1998), Gimbutas' homeland theory is completely incompatible with the linguistic evidence. Krell compiles lists of items of flora, fauna, economy, and technology that archaeology has accounted for in the Kurgan culture and compares it with lists of the same categories as reconstructed by traditional historical-Indo-European linguistics. Krell finds major discrepancies between the two, and underlines the fact that we cannot presume that the reconstructed term for 'horse', for example, referred to the domesticated equid in the protoperiod just because it did in later times. It could originally have referred to a wild equid, a possibility that would "undermine the mainstay of Gimbutas's arguments that the Kurgan culture first domesticated the horse and used this new technology to spread to surrounding areas."[36][37]

Pastoralism vs. agriculture

Kathrin Krell (1998) finds that the terms found in the reconstructed Indo-European language are not compatible with the cultural level of the Kurgans. Krell holds that the Indo-Europeans had agriculture whereas the Kurgan people were "just at a pastoral stage" and hence might not have had sedentary agricultural terms in their language, despite the fact that such terms are part of a Proto-Indo-European core vocabulary.[36]

Krell (1998), "Gimbutas' Kurgans-PIE homeland hypothesis: a linguistic critique", points out that the Proto-Indo-European had an agricultural vocabulary and not merely a pastoral one. As for technology, there are plausible reconstructions suggesting knowledge of navigation, a technology quite atypical of Gimbutas' steppe-centered Kurgan society. Krell concludes that Gimbutas seems to first establish a Kurgan hypothesis, based on purely archaeological observations, and then proceeds to create a picture of the PIE homeland and subsequent dispersal which fits neatly over her archaeological findings. The problem is that in order to do this, she has had to be rather selective in her use of linguistic data, as well as in her interpretation of that data.[36][37]

See also

- Tumulus

- Yamna culture

- Hamangia culture

- Domestication of the horse

- Animal sacrifice

- Ashvamedha

- Shaft tomb

- Late Glacial Maximum

- Competing hypotheses

- Proto-Indo-European Urheimat hypotheses

- Armenian hypothesis

- Anatolian hypothesis

- Out of India theory

- Paleolithic Continuity Theory

Notes

- ↑ See:

- Mallory: "The Kurgan solution is attractive and has been accepted by many archaeologists and linguists, in part or total. It is the solution one encounters in the Encyclopædia Britannica and the Grand Dictionnaire Encyclopédique Larousse."[1]

- Strazny: "The single most popular proposal is the Pontic steppes (see the Kurgan hypothesis)..."[2]

- 1 2 Parpola in Blench & Spriggs (1999:181). "The history of the Indo-European words for 'horse' shows that the Proto-Indo-European speakers had long lived in an area where the horse was native and/or domesticated (Mallory 1989:161–63). The first strong archaeological evidence for the domestication of the horse comes from the Ukrainian Srednij Stog culture, which flourished c. 4200–3500 BC and is likely to represent an early phase of the Proto-Indo-European culture (Anthony 1986:295f.; Mallory 1989:162, 197–210). During the Pit Grave culture (c. 3500–2800 BC), which continued the cultures related to Srednij Stog and probably represents the late phase of the Proto-Indo-European culture – full-scale pastoral technology, including the domesticated horse, wheeled vehicles, stock breeding and limited horticulture, spread all over the Pontic steppes, and, c. 3000 BC, in practically every direction from this centre (Anthony 1986, 1991; Mallory 1989, vol. 1).

- ↑ >Gimbutas (1970) page 156: "The name Kurgan culture (the Barrow culture) was introduced by the author in 1956 as a broader term to replace and Pit-Grave (Russian Yamna), names used by Soviet scholars for the culture in the eastern Ukraine and south Russia, and Corded Ware, Battle-Axe, Ochre-Grave, Single-Grave and other names given to complexes characterized by elements of Kurgan appearance that formed in various parts of Europe"

References

- ↑ Mallory 1989, p. 185.

- ↑ Strazny 2000, p. 163.

- ↑ Gimbutas (1985) page 190.

- ↑ Otto Schrader (1890). Sprachvergleichung und Urgeschichte, vol. 2. Jena, Ger.: Hermann Costanoble.

- ↑ Rydberg, Viktor (1907). Teutonic Mythology 1. London, UK: Norrœna. p. 19. Archived from the original on 2013-01-21.

- ↑ Karl Brugmann (1886). Grundriss der vergleichenden Grammatik der indogermanischen Sprachen, vol. 1.1, Strassburg 1886, p. 2.

- ↑ Karl Brugmann (1904). Kurze vergleichende Grammatik der indogermanischen Sprachen, vol. 1, Strassburg 1902, p. 22-23.

- ↑ Ernst Wahle (1932). Deutsche Vorzeit, Leipzig 1932.

- ↑ Gimbutas, Marija (1963). The Balts. London, UK: Thames & Hudson. p. 38. Archived from the original on 2013-10-30.

- ↑ Anthony, David W. (2007). The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. pp. 18, 495. ISBN 978-0-691-05887-0.

- 1 2 David Anthony, The Horse, The Wheel and Language: How Bronze-Age riders from the Eurasian steppes shaped the modern world (2007), pp. 306–7: "Why not a Kurgan Culture?"

- ↑ David Anthony, The Horse, The Wheel and Language: How Bronze-Age riders from the Eurasian steppes shaped the modern world (2007), p. 297.

- ↑ Razib Khan, Facing the ocean, Discover Magazine, 28 August 2012.

- ↑ T. Zerjal et al, The use of Y-chromosomal DNA variation to investigate population history: recent male spread in Asia and Europe, in S.S. Papiha, R. Deka and R. Chakraborty (eds.), Genomic Diversity: applications in human population genetics (1999), pp. 91–101.

- ↑ L. Quintana-Murci et al., Y-Chromosome lineages trace diffusion of people and languages in Southwestern Asia, American Journal of Human Genetics vol. 68 (2001), pp. 537–542.

- ↑ R.S. Wells et al, The Eurasian Heartland: A continental perspective on Y-chromosome diversity, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 98 no.18 (2001), pp. 10244–10249.

- ↑ C. Bouakaze et al, First successful assay of Y-SNP typing by SNaPshot minisequencing on ancient DNA, International Journal of Legal Medicine, vol. 121 (2007), pp. 493–499; C. Keyser et al, Ancient DNA provides new insights into the history of south Siberian Kurgan people, Human Genetics, vol. 126, no. 3 (September 2009), pp. 395–410.

- ↑ Chunxiang Li etal., Evidence that a West-East admixed population lived in the Tarim Basin as early as the early Bronze Age, BMC Biology, vol. 8, no. 15(2010).

- ↑ Marc Haber et al., "Afghanistan's Ethnic Groups Share a Y-Chromosomal Heritage Structured by Historical Events", PLoS ONE 2012, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034288

- ↑ C. Bouakaze et al., Pigment phenotype and biogeographical ancestry from ancient skeletal remains: inferences from multiplexed autosomal SNP analysis, International Journal of Legal Medicine (2009).

- ↑ W. Haak, et al., Ancient DNA, Strontium isotopes, and osteological analyses shed light on social and kinship organization of the Later Stone Age, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 105, no. 47 (2008), pp. 18226–18231.

- ↑ Haak, W.; Lazaridis, I.; Patterson, N.; Rohland, N.; Mallick, S.; Llamas, B.; Brandt, G.; Nordenfelt, S.; Harney, E.; Stewardson, K.; Fu, Q.; Mittnik, A.; Bánffy, E.; Economou, C.; Francken, M.; Friederich, S.; Pena, R. G.; Hallgren, F.; Khartanovich, V.; Khokhlov, A.; Kunst, M.; Kuznetsov, P.; Meller, H.; Mochalov, O.; Moiseyev, V.; Nicklisch, N.; Pichler, S. L.; Risch, R.; Rojo Guerra, M. A.; et al. (2015). "Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe" (PDF). Nature. doi:10.1038/nature14317. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (4 March 2015) Genetic study revives debate on origin and expansion of Indo-European languages in Europe Science Daily, Retrieved 19 April 2015

- ↑ The New Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th edition, 22:587–588

- ↑ Ivanova, Mariya (2007). "The Chronology of the "Maikop Culture" in the North Caucasus: Changing Perspectives". Armenian Journal of Near Eastern Studies II: 7–39.

- ↑ Pre- & protohistorie van de lage landen, onder redactie van J.H.F. Bloemers & T. van Dorp 1991. De Haan/Open Universiteit. ISBN 90-269-4448-9, NUGI 644

- ↑ The Germanic Invasions, the making of Europe 400–600 AD – Lucien Musset, ISBN 1-56619-326-5, p 7

- ↑ Schmoeckel 1999

- ↑ In Search of the Indo-Europeans – J.P.Mallory, Thames and Hudson 1989, p.245,ISBN 0-500-27616-1

- ↑ Koryakova 1998b.

- ↑ Koryakova 1998a.

- ↑ Anthony 2009.

- ↑ Gimbutas (1982:1)

- ↑ Gimbutas, Dexter & Jones-Bley (1997:309)

- ↑ Mallory (1991:185)

- ↑ The spread of the Indo-Europeans – Frederik Kortlandt, 1989

- 1 2 3 4 Edwin Bryant. The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate. Oxford University. pp. 39–44.

- 1 2 Philippe Blanchard, Dimitri Volchenkov (2011). Random Walks and Diffusions on Graphs and Databases: An Introduction. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 139–145.

Sources

- Anthony, David W. (2007), The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-05887-3

- Anthony, David; Vinogradov, Nikolai (1995), "Birth of the Chariot", Archaeology 48 (2), pp. 36–41.

- Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew, eds. (1999), Archaeology and Language, III: Artefacts, languages and texts, London: Routledge.

- Dexter, Miriam Robbins; Jones-Bley, Karlene, eds. (1997), The Kurgan Culture and the Indo-Europeanization of Europe: Selected Articles From 1952 to 1993, Washington, DC: Institute for the Study of Man, ISBN 0-941694-56-9.

- Gimbutas, Marija (1956), The Prehistory of Eastern Europe. Part I: Mesolithic, Neolithic and Copper Age Cultures in Russia and the Baltic Area, Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum.

- Gimbutas, Marija (1970), "Proto-Indo-European Culture: The Kurgan Culture during the Fifth, Fourth, and Third Millennia B.C.", in Cardona, George; Hoenigswald, Henry M.; Senn, Alfred, Indo-European and Indo-Europeans: Papers Presented at the Third Indo-European Conference at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 155–197, ISBN 0-8122-7574-8.

- Gimbutas, Marija (1982), "Old Europe in the Fifth Millenium B.C.: The European Situation on the Arrival of Indo-Europeans", in Polomé, Edgar C., The Indo-Europeans in the Fourth and Third Millennia, Ann Arbor: Karoma Publishers, ISBN 0-89720-041-1

- Gimbutas, Marija (Spring–Summer 1985), "Primary and Secondary Homeland of the Indo-Europeans: comments on Gamkrelidze-Ivanov articles", Journal of Indo-European Studies 13 (1&2): 185–201

- Gimbutas, Marija; Dexter, Miriam Robbins; Jones-Bley, Karlene (1997), The Kurgan Culture and the Indo-Europeanization of Europe: Selected Articles from 1952 to 1993, Washington, D. C.: Institute for the Study of Man, ISBN 0-941694-56-9

- Gimbutas, Marija; Dexter, Miriam Robbins (1999), The Living Goddesses, Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-22915-0

- Krell, Kathrin (1998). "Gimbutas' Kurgans-PIE homeland hypothesis: a linguistic critique". Chapter 11 in "Archaeology and Language, II", Blench and Spriggs.

- Mallory, J.P.; Adams, D.Q., eds. (1997), Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, London: Fitzroy Dearborn, ISBN 1-884964-98-2.

- Mallory, J.P. (1991), In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology, and Myth, London: Thames & Hudson, ISBN 0-500-27616-1.

- Mallory, J.P. (1996), Fagan, Brian M., ed., The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-507618-4

- Renfrew, Colin. (1999). "Time depth, convergence theory, and innovation in Proto-Indo-European: 'Old Europe' as a PIE linguistic area." J INDO-EUR STUD, 27(3-4), 257-293.

- Schmoeckel, Reinhard (1999), Die Indoeuropäer. Aufbruch aus der Vorgeschichte ("The Indo-Europeans: Rising from pre-history"), Bergisch-Gladbach (Germany): Bastei Lübbe, ISBN 3-404-64162-0

- Strazny, Philipp (Ed). (2000), Dictionary of Historical and Comparative Linguistics (1 ed.), Routledge, ISBN 978-1-57958-218-0

- Zanotti, D. G. (1982), "The Evidence for Kurgan Wave One As Reflected By the Distribution of 'Old Europe' Gold Pendants", Journal of Indo-European Studies 10, pp. 223–234.

Further reading

- Anthony, David W. (2007), The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-05887-3

External links

- humanjourney.us, The Indo-Europeans

- Charlene Spretnak (2011), Anatomy of a Backlash: Concerning the Work of Marija Gimbutas, Journal of Archaeomythology