Kurds

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 30–32 million[1][2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| |

estimates from 12 to 16 million 15.7–25%[1][3][4][5] |

| |

estimates from 3.35 million to 8 million, 5–10%[6][7][1][4] |

| |

estimates from 4 to 6.5 million, 15–23%[8][1][4][9][10] |

| |

estimates from 1.3 to 2.5 million, 6–15%[11][12][13][14][4][15][16][17][18][19] |

| | 37,500[20] |

| | 20,800[21] |

| | 6,100[22] |

| Diaspora | c. 2 million |

| | 800,000[23] |

| | 150,000[24] |

| | 83,600[25] |

| | 80,000[26] |

| | 70,000[27] |

| | 63,800[28] |

| | 50,000[29][30][31] |

| | 42,300[32] |

| | 35,000[33] |

| | 30,000[34] |

| | 30,000[35] |

| | 23,000[36] |

| | 22,000[37] |

| | 15,400[38] |

| | 13,200[39][40] |

| | 11,685[41] |

| | 10,700[42] |

| | 7,000[43] |

| Languages | |

|

Kurdish and Zaza–Gorani In their different forms: Sorani, Kurmanji, Pehlewani, Zaza, Gorani | |

| Religion | |

|

majority Islam since 7. century (Sunni Muslim, but also Shia Muslim and Sufism) with minorities of deism, agnosticism, Yazdânism, Zoroastrianism, Christianity and Judaism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Iranian peoples | |

| Part of a series on Kurdish history and Kurdish culture |

|

The Kurds (Kurdish: کورد Kurd) are an ethnic group in the Middle East, mostly inhabiting a contiguous area spanning adjacent parts of eastern and southeastern Turkey (Northern Kurdistan), western Iran (Eastern or Iranian Kurdistan), northern Iraq (Southern or Iraqi Kurdistan), and northern Syria (Western Kurdistan or Rojava).[44] The Kurds have ethnically diverse origins.[45][46] They are culturally and linguistically closely related to the Iranian peoples[45][47][48] and, as a result, are often themselves classified as an Iranian people.[49] Kurdish nationalists claim that the Kurds are descended from the Hurrians and the Medes,[50] (the latter being another Iranian people[51]) and the claimed Median descent is reflected in the words of the Kurdish national anthem: "we are the children of the Medes and Kai Khosrow".[52] The Kurdish languages form a subgroup of the Northwestern Iranian languages.[53][54]

The Kurds are estimated to number, worldwide, around 30–32 million, possibly as high as 37 million,[55] with the majority living in West Asia; however there are significant Kurdish diaspora communities in the cities of western Turkey, in particular Istanbul. A recent Kurdish diaspora has also developed in Western countries, primarily in Germany. The Kurds are the majority population in the autonomous region of Iraqi Kurdistan and in the autonomous region of Rojava, and are a significant minority group in the neighboring countries Turkey and Iran, where Kurdish nationalist movements continue to pursue greater autonomy and cultural rights.

Name

The exact origins of the name Kurd are unclear.[56] The underlying toponym is recorded in Assyrian as Qardu and in Middle Bronze Age Sumerian as Kar-da.[57] Assyrian Qardu refers to an area in the upper Tigris basin, and it is presumably reflected in corrupted form in Arabic (Quranic) Ǧūdī, re-adopted in Kurdish as Cûdî.[58]

The name would be continued as the first element in the toponym Corduene, mentioned by Xenophon as the tribe who opposed the retreat of the Ten Thousand through the mountains north of Mesopotamia in the 4th century BC.

There are, however, dissenting views, which do not derive the name of the Kurds from Qardu and Corduene but opt for derivation from Cyrtii (Cyrtaei) instead.[59]

Regardless of its possible roots in ancient toponymy, the ethnonym Kurd might be derived from a term kwrt- used in Middle Persian as a common noun to refer to "nomads" or "tent-dwellers", which could be applied as an attribute to any Iranian group with such a lifestyle.[60]

The term gained the characteristic of an ethnonym following the Muslim conquest of Persia, as it was adopted into Arabic and gradually became associated with an amalgamation of Iranian and Iranicised tribes and groups in the region.[61][62]

It is also hypothesized that Kurd could originate from the Persian word gord (see Shahrekord), because the Arabic script lacks a symbol corresponding uniquely to g (گ).

Sherefxan Bidlisi in the 16th century states that there are four division of "Kurds": Kurmanj, Lur, Kalhor and Guran, each of which speak a different dialect or language variation. Paul (2008) notes that the 16th-century usage of the term Kurd as recorded by Bidlisi, regardless of linguistic grouping, might still reflect an incipient Northwestern Iranian "Kurdish" ethnic identity uniting the Kurmanj, Kalhur, and Guran.[53]

Language

.jpg)

The Kurdish language (Kurdish: Kurdî or کوردی) refers collectively to the related dialects spoken by the Kurds.[53] It is mainly spoken in those parts of Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey which comprise Kurdistan.[63] Kurdish holds official status in Iraq as a national language alongside Arabic, is recognized in Iran as a regional language, and in Armenia as a minority language.

The Kurdish languages belong to the northwestern sub‑group of the Iranian languages, which in turn belongs to the Indo-Iranian branch of the Indo-European family.

Most Kurds are either bilingual or multilingual, speaking the language of their respective nation of origin, such as Arabic, Persian, and Turkish as a second language alongside their native Kurdish, while those in diaspora communities often speak 3 or more languages.

According to Mackenzie, there are few linguistic features that all Kurdish dialects have in common and that are not at the same time found in other Iranian languages.[64]

The Kurdish dialects according to Mackenzie are classified as:[65]

- Northern group (the Kurmanji dialect group)

- Central group (part of the Sorani dialect group)

- Southern group (part of the Sorani dialect group) including Kermanshahi, Ardalani and Laki

The Zaza and Gorani are ethnic Kurds,[66] but the Zaza–Gorani languages are not classified as Kurdish.

Commenting on the differences between the dialects of Kurdish, Kreyenbroek clarifies that in some ways, Kurmanji and Sorani are as different from each other as English and German, giving the example that Kurmanji has grammatical gender and case endings, but Sorani does not, and observing that referring to Sorani and Kurmanji as "dialects" of one language is supported only by "their common origin...and the fact that this usage reflects the sense of ethnic identity and unity of the Kurds."[67]

Population

The number of Kurds living in Southwest Asia is estimated at close to 30 million, with another one or two million living in diaspora. Kurds comprise anywhere from 18% to 20% of the population in Turkey,[1] possibly as high as 25%;[2] 15 to 20% in Iraq;[1] 10% in Iran;[1] and 9% in Syria.[1][68] Kurds form regional majorities in all four of these countries, viz. in Turkish Kurdistan, Iraqi Kurdistan, Iranian Kurdistan and Syrian Kurdistan. The Kurds are the fourth largest ethnic groups in West Asia after the Arabs, Persians, and Turks.

The total number of Kurds in 1991 was placed at 22.5 million, with 48% of this number living in Turkey, 18% in Iraq, 24% in Iran, and 4% in Syria.[69]

Recent emigration accounts for a population of close to 1.5 million in Western countries, about half of them in Germany.

A special case are the Kurdish populations in the Transcaucasus and Central Asia, displaced there mostly in the time of the Russian Empire, who underwent independent developments for more than a century and have developed an ethnic identity in their own right.[70] This groups' population was estimated at close to 0.4 million in 1990.[71]

History

Antiquity

The term "Kurd" is first encountered in Arabic sources of the seventh century.[72] Books from the early Islamic era, including those containing legends like the Shahnameh and the Middle Persian Kar-Namag i Ardashir i Pabagan and other early Islamic sources provide early attestation of the name Kurd.[73]

During Sassanid era, in Kar-Namag i Ardashir i Pabagan, a short prose work written in Middle Persian, Ardashir I is depicted as having battled the Kurds and their leader, Madig. After initially sustaining a heavy defeat, Ardashir I was successful in subjugating the Kurds.[74] In a letter Ardashir I received from his foe, Ardavan V, which is also featured in the same work, he is referred to as being a Kurd himself.

You've bitten off more than you can chew

and you have brought death to yourself.

O son of a Kurd, raised in the tents of the Kurds,

who gave you permission to put a crown on your head?[1]

- ^ J. Limbert (1968). The Origins and Appearance of the Kurds in Pre-Islamic Iran. Iranian Studies, 1.2: pp. 41-51

The usage of the term Kurd during this time period most likely was a social term, designating Iranian nomads, rather than a concrete ethnic group.[75][76]

Similarly, in AD 360, the Sassanid king Shapur II marched into the Roman province Zabdicene, to conquer its chief city, Bezabde, present-day Cizre. He found it heavily fortified, and guarded by three legions and a large body of Kurdish archers.[77] After a long and hard-fought siege, Shapur II breached the walls, conquered the city and massacred all its defenders. Hereafter he had the strategically located city repaired, provisioned and garrisoned with his best troops.[77]

There is also a 7th-century text by an unidentified author, written about the legendary Christian martyr Mar Qardagh. He lived in the 4th century, during the reign of Shapur II, and during his travels is said to have encountered Mar Abdisho, a deacon and martyr, who, after having been questioned of his origins by Mar Qardagh and his Marzobans, stated that his parents were originally from an Assyrian village called Hazza, but were driven out and subsequently settled in Tamanon, a village in the land of the Kurds, identified as being in the region of Mount Judi.[78]

Medieval period

In the early Middle Ages, the Kurds sporadically appear in Arabic sources, though the term was still not being used for a specific people; instead it referred to an amalgam of nomadic western Iranic tribes, who were distinct from Persians. However, in the High Middle Ages, the Kurdish ethnic identity gradually materialized, as one can find clear evidence of the Kurdish ethnic identity and solidarity in texts of the 12th and 13th century,[79] though, the term was also still being used in the social sense.[80]

Al-Tabari wrote that in 639, Hormuzan, a Sasanian general originating from a noble family, battled against the Islamic invaders in Khuzestan, and called upon the Kurds to aid him in battle.[81] They were defeated however, and brought under Islamic rule.

In 838, a Kurdish leader based in Mosul, named Mir Jafar, revolted against the Caliph Al-Mu'tasim who sent the commander Itakh to combat him. Itakh won this war and executed many of the Kurds.[82][83] Eventually Arabs conquered the Kurdish regions and gradually converted the majority of Kurds to Islam, often incorporating them into the military, such as the Hamdanids whose dynastic family members also frequently intermarried with Kurds.[84][85]

In 934 the Daylamite Buyid dynasty was founded, and subsequently conquered most of present-day Iran and Iraq. During the time of rule of this dynasty, Kurdish chief and ruler, Badr ibn Hasanwaih, established himself as one of the most important emirs of the time.[86]

In the 10th-12th centuries, a number of Kurdish principalities and dynasties were founded, ruling Kurdistan and neighbouring areas:

- The Shaddadids (951–1174) ruled parts of present-day Armenia and Arran.[87]

- The Rawadid (955–1221) ruled Azerbaijan.[88]

- The Hasanwayhids (959–1015) ruled western Iran and upper Mesopotamia.[89]

- The Marwanids (990–1096) ruled eastern Anatolia.[90]

- The Annazids (990–1117) ruled western Iran and upper Mesopotamia (succeeded the Hasanwayhids).[91]

- The Kakuyids (1008–1051) ruled Isfahan, Yazd and Abarkuh.[92]

- The Hazaraspids (1148–1424) ruled southwestern Iran.[93]

- The Ayyubids (1171–1341) ruled parts of southeastern Anatolia, the Arabian Peninsula and North Africa.[94]

Due to the Turkic invasion of Anatolia, the 11th century Kurdish dynasties crumbled and became incorporated into the Seljuk Dynasty. Kurds would hereafter be used in great numbers in the armies of the Zengids.[95] Succeeding the Zengids, the Kurdish Ayyubids established themselves in 1171, first under the leadership of Saladin. Saladin led the Muslims to recapture the city of Jerusalem from the Crusaders at the Battle of Hattin; also frequently clashing with the Hashashins. The Ayyubid dynasty lasted until 1341 when the Ayyubid sultanate fell to Mongolian invasions.

Safavid period

The Safavid Dynasty, established in 1501, also established its rule over Kurdish territories. The paternal line of this family actually had Kurdish roots, tracing back to Firuz-Shah Zarrin-Kolah, a dignitary who moved from Kurdistan to Ardabil in the 11th century.[96][97] The Battle of Chaldiran in 1514 that culminated in what is nowadays Iran's West Azerbaijan Province, marked the start of frequent warfare between the Iranian Safavids (and successive Iranian dynasties) and the neighbouring rivalling Ottomans. By this war, many of the Kurds would be, as well as in the coming centuries to come, relatively frequently be passed on between the former and latter, as they conquered or lost territories.

Despite many of the Kurds remained under Safavid rule till its fall, nevertheless, the Kurds would revolt several times against the former. Shah Ismail I put down a Yezidi rebellion which went on from 1506-1510. A century later, the year-long Battle of Dimdim took place, wherein Shah Abbas I succeeded in putting down the rebellion led by Amir Khan Lepzerin. Hereafter, a large number of Kurds was deported to Khorasan, not only to weaken the Kurds, but also to protect the eastern border from invading Afghan and Turkmen tribes.[98] Forced movements and deportations in a by the Safavids clever usage of geo-political play was also furthermore to be used by Abbas I against other ethnic groups of his vast empire, such as the Armenians, Georgians, and Circassians, who were moved from and towards other districts in his empire, although the eventual reasons and performances could differ case to case. Kurds were found in great numbers at the slave markets of Khiva and Bukhara, being sold by the Turkmens. The Kurds of Khorasan, numbering around 700,000, still use the Kurmanji Kurdish dialect.[99][100]

Zand Period

After the fall of the Safavids, Iran fell was under the control of the Afsharid Empire ruled by Nader Shah at its peak. Yet After Nader's death Iran fell into civil war, with multiple leaders trying to gain control over the country. Ultimately, it was Karim Khan, a Laki general of the Zand tribe who would come to power.[101] The country would flourish during Karim Khan’s reign; a strong resurgence of the arts would take place, and international ties were strengthened.[102] Karim Khan was portrayed as being a ruler who truly cared about his subjects, thereby gaining the title Vakil e-Ra’aayaa (meaning Representative of the People in Persian).[102] Though not as powerful in its geo-political and military reach as the predecessing Safavids and Afsharids or even the early Qajars, even despite that he managed to reassert Iranian hegemony over several of its integral territories in the Caucasus, comprising parts of modern-day Azerbaijan. In Ottoman Iraq, following the Ottoman–Persian War (1775–76), he managed to seize Basra for several years.[103][104]

After Karim Khan's death, the dynasty would decline in favor of the rivaling Qajars due to infighting between the Khan’s incompetent offspring. It wasn't until Lotf Ali Khan, 10 years later, that the dynasty would once again be led by an adept ruler. By this time however, the Qajars had already progressed greatly, having taken a number of Zand territories. Lotf Ali Khan made multiple successes before ultimately succumbing to the rivaling faction. Iran and all its Kurdish territories would hereby be incorporated in the Qajar Dynasty.

The Kurdish tribes present in Baluchistan and some of those in Fars are believed to be remnants of those that assisted and accompanied Lotf Ali Khan and Karim Khan, respectively.[105]

Ottoman period

When Sultan Selim I, after defeating Shah Ismail I in 1514, annexed Western Armenia and Kurdistan, he entrusted the organisation of the conquered territories to Idris, the historian, who was a Kurd of Bitlis. He divided the territory into sanjaks or districts, and, making no attempt to interfere with the principle of heredity, installed the local chiefs as governors. He also resettled the rich pastoral country between Erzerum and Erivan, which had lain in waste since the passage of Timur, with Kurds from the Hakkari and Bohtan districts. For the next centuries, from the Peace of Amasya until the first half of the 19th century, several regions of the wide Kurdish homelands would be contested as well between the Ottomans and the neighboring rivalling successive Iranian dynasties (Safavids, Afsharids, Qajars) in the frequent Ottoman-Persian Wars.

The Ottoman centralist policies in the beginning of the 19th century aimed to remove power from the principalities and localities, which directly affected the Kurdish emirs. Bedirhan Bey was the last emir of the Cizre Bohtan Emirate after initiating an uprising in 1847 against the Ottomans to protect the current structures of the Kurdish principalities. Although his uprising is not classified as a nationalist one, his children played significant roles in the emergence and the development of Kurdish nationalism through the next century.[106]

The first modern Kurdish nationalist movement emerged in 1880 with an uprising led by a Kurdish landowner and head of the powerful Shemdinan family, Sheik Ubeydullah, who demanded political autonomy or outright independence for Kurds as well as the recognition of a Kurdistan state without interference from Turkish or Persian authorities.[107] The uprising against Qajar Persia and the Ottoman Empire was ultimately suppressed by the Ottomans and Ubeydullah, along with other notables, were exiled to Istanbul.

20th century

Kurdish nationalism emerged after World War I with the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire which had historically successfully integrated (but not assimilated) the Kurds, through use of forced repression of Kurdish movements to gain independence. Revolts did occur sporadically but only in 1880 with the uprising led by Sheik Ubeydullah were demands as an ethnic group or nation made. Ottoman sultan Abdul Hamid responded by a campaign of integration by co-opting prominent Kurdish opponents to strong Ottoman power with prestigious positions in his government. This strategy appears successful given the loyalty displayed by the Kurdish Hamidiye regiments during World War I.[108]

The Kurdish ethnonationalist movement that emerged following World War I and end of the Ottoman Empire was largely reactionary to the changes taking place in mainstream Turkey, primarily radical secularization which the strongly Muslim Kurds abhorred, centralization of authority which threatened the power of local chieftains and Kurdish autonomy, and rampant Turkish nationalism in the new Turkish Republic which obviously threatened to marginalize them.[109]

Jakob Künzler, head of a missionary hospital in Urfa, has documented the large scale ethnic cleansing of both Armenians and Kurds by the Young Turks.[110] He has given a detailed account of deportation of Kurds from Erzurum and Bitlis in winter of 1916. The Kurds were perceived to be subversive elements that would take the Russian side in the war. In order to eliminate this threat, Young Turks embarked on a large scale deportation of Kurds from the regions of Djabachdjur, Palu, Musch, Erzurum and Bitlis. Around 300,000 Kurds were forced to move southwards to Urfa and then westwards to Aintab and Marasch. In the summer of 1917, Kurds were moved to Konya in central Anatolia. Through these measures, the Young Turk leaders aimed at eliminating the Kurds by deporting them from their ancestral lands and by dispersing them in small pockets of exiled communities. By the end of World War I, up to 700,000 Kurds were forcibly deported and almost half of the displaced perished.[111]

Some of the Kurdish groups sought self-determination and the confirmation of Kurdish autonomy in the Treaty of Sèvres; in the aftermath of World War I, Kemal Atatürk prevented such a result. Kurds backed by the United Kingdom declared independence in 1927 and established the Republic of Ararat. Turkey suppressed Kurdist revolts in 1925, 1930, and 1937–1938, while Iran did the same in the 1920s to Simko Shikak at Lake Urmia and Jaafar Sultan of the Hewraman region, who controlled the region between Marivan and north of Halabja. A short-lived Soviet-sponsored Kurdish Republic of Mahabad in Iran did not long outlast World War II.

From 1922–1924 in Iraq a Kingdom of Kurdistan existed. When Ba'athist administrators thwarted Kurdish nationalist ambitions in Iraq, war broke out in the 1960s. In 1970 the Kurds rejected limited territorial self-rule within Iraq, demanding larger areas including the oil-rich Kirkuk region.

During the 1920s and 1930s, several large scale Kurdish revolts took place in Kurdistan. Following these rebellions, the area of Turkish Kurdistan was put under martial law and a large number of the Kurds were displaced. Government also encouraged resettlement of Albanians from Kosovo and Assyrians in the region to change the population makeup. These events and measures led to a long-lasting mutual distrust between Ankara and the Kurds .[112] During the relatively open government of the 1950s, Kurds gained political office and started working within the framework of the Turkish Republic to further their interests but this move towards integration was halted with the 1960 Turkish coup d'état.[108] The 1970s saw an evolution in Kurdish nationalism as Marxist political thought influenced some new generation of Kurdish nationalists opposed to the local feudal authorities who had been a traditional source of opposition to authority; eventually they would form the militant separatist organization PKK, also known as the Kurdistan Workers' Party in English. The Kurdistan Workers' Party later abandoned Marxism-Leninism.[113]

Kurds are often regarded as "the largest ethnic group without a state",[114][115][116][117][118][119] although larger stateless nations exist. Such periphrasis is rejected by some researchers like Martin van Bruinessen[120] and some other scholars who are usually close to Turkish authorities believe that such claims obscures Kurdish cultural, social, political and ideological heterogeneity without sufficient explanation.[121][122][123] Michael Radu who had worked for the United States's Pennsylvania Foreign Policy Research Institute argued that such claims mostly come from Kurdish nationalists, Western human rights activists and leftists in Europe.[121]

Kurdish communities

Turkey

According to CIA Factbook, Kurds formed approximately 18% of the population in Turkey (approximately 14 million) in 2008. One Western source estimates that up to 25% of the Turkish population is Kurdish (approximately 18-19 million people).[2] Kurdish sources claim there are as many as 20 or 25 million Kurds in Turkey.[124] In 1980, Ethnologue estimated the number of Kurdish-speakers in Turkey at around five million,[125] when the country's population stood at 44 million.[126] Kurds form the largest minority group in Turkey, and they have posed the most serious and persistent challenge to the official image of a homogeneous society. This classification was changed to the new euphemism of Eastern Turk in 1980.[127] Nowadays the Kurds, in Turkey, are still known under the name Easterner (Doğulu).

Several large scale Kurdish revolts in 1925, 1930 and 1938 were suppressed by the Turkish government and more than one million Kurds were forcibly relocated between 1925 and 1938. The use of Kurdish language, dress, folklore, and names were banned and the Kurdish-inhabited areas remained under martial law until 1946.[128] The Ararat revolt, which reached its apex in 1930, was only suppressed after a massive military campaign including destruction of many villages and their populations. In quelling the revolt, Turkey was assisted by the close cooperation of its neighboring states such as Soviet Union, Iran and Iraq.[129] The revolt was organized by a Kurdish party called Khoybun which signed a treaty with the Dashnaksutyun (Armenian Revolutionary Federation) in 1927.[129] By the 1970s, Kurdish leftist organizations such as Kurdistan Socialist Party-Turkey (KSP-T) emerged in Turkey which were against violence and supported civil activities and participation in elections. In 1977, Mehdi Zana a supporter of KSP-T won the mayoralty of Diyarbakir in the local elections. At about the same time, generational fissures gave birth to two new organizations: the National Liberation of Kurdistan and the Kurdistan Workers Party.[130]

The Partiya Karkerên Kurdistan (PKK), also known as KADEK and Kongra-Gel is Kurdish militant organization which has waged an armed struggle against the Turkish state for cultural and political rights and self-determination for the Kurds. Turkey's military allies the US, the EU, and NATO see the PKK as a terrorist organization while the UN,[131] Switzerland,[132] Russia,[133] China and India have refused to add the PKK to their terrorist list.[134] Some of them have even supported the PKK.[135]

Between 1984 and 1999, the PKK and the Turkish military engaged in open war, and much of the countryside in the southeast was depopulated, as Kurdish civilians moved from villages to bigger cities such as Diyarbakır, Van, and Şırnak, as well as to the cities of western Turkey and even to western Europe. The causes of the depopulation included mainly the Turkish state's military operations, state's political actions, Turkish Deep state actions, the poverty of the southeast and PKK atrocities against Kurdish clans which were against them.[136] Turkish State actions has included forced inscription, forced evacuation, destruction of villages, severe harassment, illegal arrests and executions of Kurdish civilians.[137][138][139][140]

Since the 1970s, the European Court of Human Rights has condemned Turkey for the thousands of human rights abuses.[137][141] The judgments are related to executions of Kurdish civilians,[138] torturing,[142] forced displacements[143] systematic destruction of villages,[144] arbitrary arrests[145] murdered and disappeared Kurdish journalists.[146]

Leyla Zana, the first Kurdish female MP from Diyarbakir, caused an uproar in Turkish Parliament after adding the following sentence in Kurdish to her parliamentary oath during the swearing-in ceremony in 1994: "I take this oath for the brotherhood of the Turkish and Kurdish peoples."[147]

In March 1994, the Turkish Parliament voted to lift the immunity of Zana and five other Kurdish DEP members: Hatip Dicle, Ahmet Turk, Sirri Sakik, Orhan Dogan and Selim Sadak. Zana, Dicle, Sadak and Dogan were sentenced to 15 years in jail by the Supreme Court in October 1995. Zana was awarded the Sakharov Prize for human rights by the European Parliament in 1995. She was released in 2004 amid warnings from European institutions that the continued imprisonment of the four Kurdish MPs would affect Turkey's bid to join the EU.[148][149] The 2009 local elections resulted in 5.7% for Kurdish political party DTP.[150]

Officially protected death squads are accused of disappearance of 3,200 Kurds and Assyrians in 1993 and 1994 in the so-called "mystery killings". Kurdish politicians, human-rights activists, journalists, teachers and other members of intelligentsia were among the victims. Virtually none of the perpetrators were investigated nor punished. Turkish government also encouraged Islamic extremist group Hezbollah to assassinate suspected PKK members and often ordinary Kurds.[151] Azimet Köylüoğlu, the state minister of human rights, revealed the extent of security forces' excesses in autumn 1994: While acts of terrorism in other regions are done by the PKK; in Tunceli it is state terrorism. In Tunceli, it is the state that is evacuating and burning villages. In the southeast there are two million people left homeless.[152]

Iran

The Kurdish region of Iran has been a part of the country since ancient times. Nearly all Kurdistan was part of Persian Empire until its Western part was lost during wars against the Ottoman Empire.[153] Following the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 Tehran had demanded all lost territories including Turkish Kurdistan, Mosul, and even Diyarbakır, but demands were quickly rejected by Western powers.[154] This area has been divided by modern Turkey, Syria and Iraq.[155] Today, the Kurds inhabit mostly northwestern territories known as Iranian Kurdistan but also the northeastern region of Khorasan, and constitute approximately 7-10%[156] of Iran's overall population (6.5–7.9 million), compared to 10.6% (2 million) in 1956 and 8% (800 thousand) in 1850.[157]

Unlike in other Kurdish-populated countries, there are strong ethnolinguistical and cultural ties between Kurds, Persians and others as Iranian peoples.[156] Some modern Iranian dynasties like the Safavids and Zands are considered to be partly of Kurdish origin. Kurdish literature in all of its forms (Kurmanji, Sorani, and Gorani) has been developed within historical Iranian boundaries under strong influence of the Persian language.[155] The Kurds sharing much of their history with the rest of Iran is seen as reason for why Kurdish leaders in Iran do not want a separate Kurdish state[156][158][159]

The government of Iran has never employed the same level of brutality against its own Kurds like Turkey or Iraq, but it has always been implacably opposed to any suggestion of Kurdish separatism.[156] During and shortly after the First World War the government of Iran was ineffective and had very little control over events in the country and several Kurdish tribal chiefs gained local political power, even established large confederations.[158] At the same time waves of nationalism from the disintegrating Ottoman Empire partly influenced some Kurdish chiefs in border regions to pose as Kurdish nationalist leaders.[158] Prior to this, identity in both countries largely relied upon religion i.e. Shia Islam in the particular case of Iran.[159][160] In 19th century Iran, Shia–Sunni animosity and the describing of Sunni Kurds as an Ottoman fifth column was quite frenquent.[161]

During the late 1910s and early 1920s, tribal revolt led by Kurdish chieftain Simko Shikak struck north western Iran. Although elements of Kurdish nationalism were present in this movement, historians agree these were hardly articulate enough to justify a claim that recognition of Kurdish identity was a major issue in Simko's movement, and he had to rely heavily on conventional tribal motives.[158] Government forces and non-Kurds were not the only ones to suffer in the attacks, the Kurdish population was also robbed and assaulted.[158][162] Rebels do not appear to have felt any sense of unity or solidarity with fellow Kurds.[158] Kurdish insurgency and seasonal migrations in the late 1920s, along with long-running tensions between Tehran and Ankara, resulted in border clashes and even military penetrations in both Iranian and Turkish territory.[154] Two regional powers have used Kurdish tribes as tool for own political benefits: Turkey has provided military help and refuge for anti-Iranian Turcophone Shikak rebels in 1918-1922,[163] while Iran did the same during Ararat rebellion against Turkey in 1930. Reza Shah's military victory over Kurdish and Turkic tribal leaders initiaded with repressive era toward non-Iranian minorities.[162] Government's forced detribalization and sedentarization in 1920s and 1930s resulted with many other tribal revolts in Iranian regions of Azerbaijan, Luristan and Kurdistan.[164] In particular case of the Kurds, this repressive policies partly contributed to developing nationalism among some tribes.[158]

As a response to growing Pan-Turkism and Pan-Arabism in region which were seen as potential threats to the territorial integrity of Iran, Pan-Iranist ideology has been developed in the early 1920s.[160] Some of such groups and journals openly advocated Iranian support to the Kurdish rebellion against Turkey.[165] Secular Pahlavi dynasty has endorsed Iranian ethnic nationalism[160] which seen the Kurds as integral part of the Iranian nation.[159] Mohammad Reza Pahlavi has personally praised the Kurds as "pure Iranians" or "one of the most noble Iranian peoples".[166] Another significant ideology during this period was Marxism which arose among Kurds under influence of USSR. It culminated in the Iran crisis of 1946 which included a separatist attempt of KDP-I and communist groups[167] to establish the Soviet puppet government[168][169][170] called Republic of Mahabad. It arose along with Azerbaijan People's Government, another Soviet puppet state.[156][171] The state itself encompassed a very small territory, including Mahabad and the adjacent cities, unable to incorporate the southern Iranian Kurdistan which fell inside the Anglo-American zone, and unable to attract the tribes outside Mahabad itself to the nationalist cause.[156] As a result, when the Soviets withdrew from Iran in December 1946, government forces were able to enter Mahabad unopposed.[156]

Several nationalist and Marxist insurgencies continued for decades (1967, 1979, 1989–96) led by KDP-I and Komalah, but those two organization have never advocated a separate Kurdish state or greater Kurdistan as did the PKK in Turkey.[158][173][174][175] Still, many of dissident leaders, among others Qazi Muhammad and Abdul Rahman Ghassemlou, were executed or assassinated.[156] During Iran–Iraq War, Tehran has provided support for Iraqi-based Kurdish groups like KDP or PUK, along with asylum for 1,400,000 Iraqi refugees, mostly Kurds. Kurdish Marxist groups have been marginalized in Iran since the dissolution of the Soviet Union. In 2004 new insurrection started by PJAK, separatist organization affiliated with the Turkey-based PKK[176] and designated as terrorist by Iran, Turkey and the USA.[176] Some analysts claim PJAK do not pose any serious threat to the government of Iran.[177] Cease-fire has been established on September 2011 following the Iranian offensive on PJAK bases, but several clashes between PJAK and IRGC took place after it.[122] Since the Iranian Revolution of 1979, accusations of "discrimination" by Western organizations and of "foreign involvement" by Iranian side have become very frequent.[122]

Kurds have been well integrated in Iranian political life during reign of various governments.[158] Kurdish liberal political Karim Sanjabi has served as minister of education under Mohammad Mossadegh in 1952.[166] During the reign of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi some members of parliament and high army officers were Kurds, and there was even a Kurdish Cabinet Minister.[158] During the reign of the Pahlavis Kurds received many favours from the authorities, for instance to keep their land after the land reforms of 1962.[158] In the early 2000s, presence of thirty Kurdish deputies in the 290-strong parliament has also helped to undermine claims of discrimination.[178] Some of influential Kurdish politicians during recent years include former first vice president Mohammad Reza Rahimi and Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, Mayor of Tehran and second-placed presidential candidate in 2013. Kurdish language is today used more than at any other time since the Revolution, including in several newspapers and among schoolchildren.[178] Large number of Kurds in Iran show no interest in Kurdish nationalism,[156] especially Shia Kurds who even vigorously reject idea of autonomy, preferring direct rule from Tehran.[156][173] Iranian national identity is questioned only in the peripheral Kurdish Sunni regions.[179]

Iraq

Kurds constitute approximately 17% of Iraq's population. They are the majority in at least three provinces in northern Iraq which are together known as Iraqi Kurdistan. Kurds also have a presence in Kirkuk, Mosul, Khanaqin, and Baghdad. Around 300,000 Kurds live in the Iraqi capital Baghdad, 50,000 in the city of Mosul and around 100,000 elsewhere in southern Iraq.[180]

Kurds led by Mustafa Barzani were engaged in heavy fighting against successive Iraqi regimes from 1960 to 1975. In March 1970, Iraq announced a peace plan providing for Kurdish autonomy. The plan was to be implemented in four years.[181] However, at the same time, the Iraqi regime started an Arabization program in the oil-rich regions of Kirkuk and Khanaqin.[182] The peace agreement did not last long, and in 1974, the Iraqi government began a new offensive against the Kurds. Moreover, in March 1975, Iraq and Iran signed the Algiers Accord, according to which Iran cut supplies to Iraqi Kurds. Iraq started another wave of Arabization by moving Arabs to the oil fields in Kurdistan, particularly those around Kirkuk.[183] Between 1975 and 1978, 200,000 Kurds were deported to other parts of Iraq.[184]

During the Iran–Iraq War in the 1980s, the regime implemented anti-Kurdish policies and a de facto civil war broke out. Iraq was widely condemned by the international community, but was never seriously punished for oppressive measures such as the mass murder of hundreds of thousands of civilians, the wholesale destruction of thousands of villages and the deportation of thousands of Kurds to southern and central Iraq.

The genocidal campaign, conducted between 1986 and 1989 and culminating in 1988, carried out by the Iraqi government against the Kurdish population was called Anfal ("Spoils of War"). The Anfal campaign led to destruction of over two thousand villages and killing of 182,000 Kurdish civilians.[185] The campaign included the use of ground offensives, aerial bombing, systematic destruction of settlements, mass deportation, firing squads, and chemical attacks, including the most infamous attack on the Kurdish town of Halabja in 1988 that killed 5000 civilians instantly.

After the collapse of the Kurdish uprising in March 1991, Iraqi troops recaptured most of the Kurdish areas and 1.5 million Kurds abandoned their homes and fled to the Turkish and Iranian borders. It is estimated that close to 20,000 Kurds succumbed to death due to exhaustion, lack of food, exposure to cold and disease. On 5 April 1991, UN Security Council passed resolution 688 which condemned the repression of Iraqi Kurdish civilians and demanded that Iraq end its repressive measures and allow immediate access to international humanitarian organizations.[186] This was the first international document (since the League of Nations arbitration of Mosul in 1926) to mention Kurds by name. In mid-April, the Coalition established safe havens inside Iraqi borders and prohibited Iraqi planes from flying north of 36th parallel.[46]:373, 375 In October 1991, Kurdish guerrillas captured Erbil and Sulaimaniyah after a series of clashes with Iraqi troops. In late October, Iraqi government retaliated by imposing a food and fuel embargo on the Kurds and stopping to pay civil servants in the Kurdish region. The embargo, however, backfired and Kurds held parliamentary elections in May 1992 and established Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG).[187]

The Kurdish population welcomed the American troops in 2003 by holding celebrations and dancing in the streets.[188][189][190][191] The area controlled by peshmerga was expanded, and Kurds now have effective control in Kirkuk and parts of Mosul. The authority of the KRG and legality of its laws and regulations were recognized in the articles 113 and 137 of the new Iraqi Constitution ratified in 2005.[192] By the beginning of 2006, the two Kurdish administrations of Erbil and Sulaimaniya were unified. On 14 August 2007, Yazidis were targeted in a series of bombings that became the deadliest suicide attack since the Iraq War began, killing 796 civilians, wounding 1,562.[193]

Syria

Kurds account for 9% of Syria's population, a total of around 1.6 million people.[194] This makes them the largest ethnic minority in the country. They are mostly concentrated in the northeast and the north, but there are also significant Kurdish populations in Aleppo and Damascus. Kurds often speak Kurdish in public, unless all those present do not. According to Amnesty International, Kurdish human rights activists are mistreated and persecuted.[195] No political parties are allowed for any group, Kurdish or otherwise.

Techniques used to suppress the ethnic identity of Kurds in Syria include various bans on the use of the Kurdish language, refusal to register children with Kurdish names, the replacement of Kurdish place names with new names in Arabic, the prohibition of businesses that do not have Arabic names, the prohibition of Kurdish private schools, and the prohibition of books and other materials written in Kurdish.[196][197] Having been denied the right to Syrian nationality, around 300,000 Kurds have been deprived of any social rights, in violation of international law.[198][199] As a consequence, these Kurds are in effect trapped within Syria. In March 2011, in part to avoid further demonstrations and unrest from spreading across Syria, the Syrian government promised to tackle the issue and grant Syrian citizenship to approximately 300,000 Kurds who had been previously denied the right.[200]

On 12 March 2004, beginning at a stadium in Qamishli (a largely Kurdish city in northeastern Syria), clashes between Kurds and Syrians broke out and continued over a number of days. At least thirty people were killed and more than 160 injured. The unrest spread to other Kurdish towns along the northern border with Turkey, and then to Damascus and Aleppo.[201][202]

As a result of Syrian civil war, since July 2012, Kurds were able to take control of large parts of Syrian Kurdistan from Andiwar in extreme northeast to Jindires in extreme northwest Syria. The Syrian Kurds started Rojava Revolution in 2013.

Transcaucasus

Between the 1930s and 1980s, Armenia was a part of the Soviet Union, within which Kurds, like other ethnic groups, had the status of a protected minority. Armenian Kurds were permitted their own state-sponsored newspaper, radio broadcasts and cultural events. During the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, many non-Yazidi Kurds were forced to leave their homes since both the Azeri and non-Yazidi Kurds were Muslim.

In 1920, two Kurdish-inhabited areas of Jewanshir (capital Kalbajar) and eastern Zangazur (capital Lachin) were combined to form the Kurdistan Okrug (or "Red Kurdistan"). The period of existence of the Kurdish administrative unit was brief and did not last beyond 1929. Kurds subsequently faced many repressive measures, including deportations, imposed by the Soviet government. As a result of the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, many Kurdish areas have been destroyed and more than 150,000 Kurds have been deported since 1988 by separatist Armenian forces.[203]

Diaspora

.jpg)

According to a report by the Council of Europe, approximately 1.3 million Kurds live in Western Europe. The earliest immigrants were Kurds from Turkey, who settled in Germany, Austria, the Benelux countries, Great Britain, Switzerland and France during the 1960s. Successive periods of political and social turmoil in the region during the 1980s and 1990s brought new waves of Kurdish refugees, mostly from Iran and Iraq under Saddam Hussein, came to Europe.[99] In recent years, many Kurdish asylum seekers from both Iran and Iraq have settled in the United Kingdom (especially in the town of Dewsbury and in some northern areas of London), which has sometimes caused media controversy over their right to remain.[204] There have been tensions between Kurds and the established Muslim community in Dewsbury,[205][206] which is home to very traditional mosques such as the Markazi. Since the beginning of the turmoil in Syria many of the refugees of the Syrian Civil War are Syrian Kurds and as a result many of the current Syrian asylum seekers in Germany are of Kurdish descent.[207][208]

There was substantial immigration of ethnic Kurds in Canada and the United States, who are mainly political refugees and immigrants seeking economic opportunity. According to a 2011 Statistics Canada household survey, there were 11,685 people of Kurdish ethnic background living in Canada,[41] and according to the 2011 Census, 10,325 Canadians spoke Kurdish language.[209] In the United States, Kurdish immigrants started to settle in large numbers in Nashville in 1976,[210] which is now home to the largest Kurdish community in the United States and is nicknamed Little Kurdistan.[211] Kurdish population in Nashville is estimated to be around 11,000.[212] Total number of ethnic Kurds residing in the United States is estimated by the US Census Bureau to be 15,400.[38] Other sources claim that there are 20,000 ethnic Kurds in the United States.[213]

Religion

As a whole, the Kurdish people are adherents to a large number of different religions and creeds, perhaps constituting the most religiously diverse people of West Asia. Traditionally, Kurds have been known to take great liberties with their practices. This sentiment is reflected in the saying "Compared to the unbeliever, the Kurd is a Muslim".[214]

Islam

Today, the majority of Kurds are Sunni Muslim, belonging to the Shafi school.

There is also a minority of Kurds who are Shia Muslims, primarily living in the Ilam and Kermanshah provinces of Iran, Central and south eastern Iraq (Fayli Kurds)

Mystical practices and participation in Sufi orders are also widespread among Kurds.[215]

The Alevis (usually considered adherents of a branch of Shia Islam with elements of Sufism) are another religious minority among the Kurds, living in Eastern Anatolia. Alevism developed out of the teachings of Haji Bektash Veli, a 13th-century mystic from Khorasan. Among the Qizilbash, the militant groups which predate the Alevis and helped establish the Safavid Dynasty, there were numerous Kurdish tribes. The American missionary Stephen van Renssalaer Trowbridge, working at Aintab (present Gaziantep) reported[216] that his Alevi acquaintances considered as their highest spiritual leaders an Ahl-i Haqq sayyid family in the Guran district.[217]

Ahl-i Haqq (Yarsan)

Ahl-i Haqq or Yarsanism is a syncretic religion founded by Sultan Sahak in the late 14th century in western Iran. Most of its adherents, totaling around 1 million, are Kurds. Its central religious text is the Kalâm-e Saranjâm, written in Gurani. In this text, the religion's basic pillars are summarized as: "The Yarsan should strive for these four qualities: purity, rectitude, self-effacement and self-abnegation".[218]

The Yarsan faith's unique features include millenarism, nativism, egalitarianism, metempsychosis, angelology, divine manifestation and dualism. Many of these features are found in Yazidism, another Kurdish faith, in the faith of Zoroastrians and in ghulat (non-mainstream Shia) groups; certainly, the names and religious terminology of the Yarsan are often explicitly of Muslim origin. Unlike other indigenous Persianate faiths, the Yarsan explicitly reject class, caste and rank, which sets them apart from the Yazidis and Zoroastrians.[219]

The Ahl-i Haqq consider the Bektashi and Alevi as kindred communities.[217]

Yazidism

Yazidism is another syncretic religion practiced among Kurdish communities, founded by Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir, an 12th-century mystic from Lebanon. Their numbers exceed 500,000. Its central religious texts are the Kitêba Cilwe and Meshaf Resh.

According to Yazidi beliefs, God created the world but left it in the care of seven holy beings or angels. The most prominent angel is Melek Taus (Kurdish: Tawûsê Melek), the Peacock Angel, God's representative on earth. Yazidis believe in the periodic reincarnation of the seven holy beings in human form.

Their holiest shrine and the tomb of the faith's founder is located in Lalish, in northern Iraq.[220]

Zoroastrianism

The Persian religion of Zoroastrianism had a major influence on the early Kurdish culture and has maintained some effect since the demise of the religion in the Middle Ages. The Kurdish philosopher Sohrevardi drew heavily from Zoroastrian teachings.[221] Ascribed to the teachings of the prophet Zoroaster, the faith's Supreme Being is Ahura Mazda. Leading characteristics, such as messianism, the Golden Rule, heaven and hell, and free will influenced other religious systems, including Second Temple Judaism, Gnosticism, Christianity, and Islam.[222]

Presently, there are a small number of Zoroastrian Kurds, most of which are recent converts. These communities have established new temples and have been attempting to recruit new members to their faith.[223] In 2015, it was claimed that up to 100,000 Iraqi Kurdish inhabitants practice Zoroastrianism;[224] Zoroastrianism has an estimated 2.6 million adherents.

Christianity

Although historically there have been various accounts of Kurdish Christians, most often these were in the form of individuals, and not as communities. However, in the 19th and 20th century various travel logs tell of Kurdish Christian tribes, as well as Kurdish Muslim tribes who had substantial Christian populations living amongst them. A significant number of these were allegedly originally Armenian or Assyrian,[225] and it has been recorded that a small number of Christian traditions have been preserved. Several Christian prayers in Kurdish have been found from earlier centuries.[226]

However, most contemporary Kurdish Christians are recent converts. Both among Turkish and Iraqi Kurds there have been an increasing number of Kurds converting to Christianity. Some communities of the Iraqi converts have formed their own evangelical churches. Prominent historical Kurdish Christians include Theophobos[227][228] and the brothers Zakare and Ivane.[229][230][231]

Culture

Kurdish culture is a legacy from the various ancient peoples who shaped modern Kurds and their society. As most other Middle Eastern populations, a high degree of mutual influences between the Kurds and their neighbouring peoples are apparent. Therefore, in Kurdish culture elements of various other cultures are to be seen. However, on the whole, Kurdish culture is closest to that of other Iranian peoples, in particular those who historically had the closest geographical proximity to the Kurds, such as the Persians and Lurs. Kurds, for instance, also celebrate Newroz (March 21) as New Year's Day.[232]

Education

A madrasa system was used before the modern era.[233][234] Mele are Islamic clerics and instructors.[235]

Women

Kurdish men and women participate in mixed-gender dancing during feasts, weddings and other social celebrations. Major Soane, a British colonial officer during World War I, noted that this is unusual among Islamic people and pointed out that in this respect Kurdish culture is more akin to that of eastern Europe than to their West Asian counterparts.[236]

Folklore and mythology

The Kurds possess a rich tradition of folklore, which, until recent times, was largely transmitted by speech or song, from one generation to the next. Although some of the Kurdish writers’ stories were well-known throughout Kurdistan; most of the stories told and sung were only written down in the 20th and 21st century. Many of these are, allegedly, centuries old.

Widely varying in purpose and style, among the Kurdish folklore one will find stories about nature, anthropomorphic animals, love, heroes and villains, mythological creatures and everyday life. A number of these mythological figures can be found in other cultures, like the Simurgh and Kaveh the Blacksmith in the broader Iranian Mythology, and stories of Shahmaran throughout Anatolia. Additionally, stories can be purely entertaining, or have an educational or religious aspect.[237]

Perhaps the most widely reoccurring element is the fox, which, through cunningness and shrewdness triumphs over less intelligent species, yet often also meets his demise.[237] Another common theme are the origins of a tribe.

Storytellers would perform in front of an audience, sometimes consisting of an entire village. People from outside the region would travel to attend their narratives, and the storytellers themselves would visit other villages to spread their tales. These would thrive especially during winter, where entertainment was hard to find as evenings had to be spent inside.[237]

Coinciding with the heterogeneous Kurdish groupings, although certain stories and elements were commonly found throughout Kurdistan, others were unique to a specific area; depending on the region, religion or dialect. The Kurdish Jews of Zakho are perhaps the best example of this; whose gifted storytellers are known to have been greatly respected throughout the region, thanks to a unique oral tradition.[238] Other examples are the mythology of the Yezidis,[239] and the stories of the Dersim Kurds, which had a substantial Armenian influence.[240]

During the criminalization of the Kurdish language after the coup d’état of 1980, dengbêj (singers) and çîrokbêj (tellers) were silenced, and many of the stories had become endangered. In 1991, the language was decriminalized, yet the now highly available radios and TV’s had as effect a diminished interest in traditional storytelling.[241] However, a number of writers have made great strides in the preservation of these tales.

Weaving

Kurdish weaving is renowned throughout the world, with fine specimens of both rugs and bags. The most famous Kurdish rugs are those from the Bijar region, in the Kurdistan Province. Because of the unique way in which the Bijar rugs are woven, they are very stout and durable, hence their appellation as the ‘Iron Rugs of Persia’. Exhibiting a wide variety, the Bijar rugs have patterns ranging from floral designs, medallions and animals to other ornaments. They generally have two wefts, and are very colorful in design.[242] With an increased interest in these rugs in the last century, and a lesser need for them to be as sturdy as they were, new Bijar rugs are more refined and delicate in design.

Another well-known Kurdish rug is the Senneh rug, which is regarded as the most sophisticated of the Kurdish rugs. They are especially known for their great knot density and high quality mountain wool.[242] They lend their name from the region of Sanandaj. Throughout other Kurdish regions like Kermanshah, Siirt, Malatya and Bitlis rugs were also woven to great extent.[243]

Kurdish bags are mainly known from the works of one large tribe: the Jaffs, living in the border area between Iran and Iraq. These Jaff bags share the same characteristics of Kurdish rugs; very colorful, stout in design, often with medallion patterns. They were especially popular in the West during the 1920s and 1930s.[244]

Handicrafts

Outside of weaving and clothing, there are many other Kurdish handicrafts, which were traditionally often crafted by nomadic Kurdish tribes. These are especially well known in Iran, most notably the crafts from the Kermanshah and Sanandaj regions. Among these crafts are chess boards, talismans, jewelry, ornaments, weaponry, instruments etc.

Kurdish blades include a distinct jambiya, with its characteristic I-shaped hilt, and oblong blade. Generally, these possess double-edged blades, reinforced with a central ridge, a wooden, leather or silver decorated scabbard, and a horn hilt, furthermore they are often still worn decoratively by older men. Swords were made as well. Most of these blades in curcilation stem from the 19th century.

Another distinct form of art from Sanandaj is 'Oroosi', a type of window where stylized wooden pieces are locked into each other, rather than being glued together. These are further decorated with coloured glass, this stems from an old belief that if light passes through a combination of seven colours it helps keep the atmosphere clean.

Among Kurdish Jews a common practice was the making of talismans, which were believed to combat illnesses and protect the wearer from malevolent spirits.

Tattoos

Adorning the body with tattoos (deq in Kurdish) is widespread among the Kurds; even though permanent tattoos are not permissible in Sunni Islam. Therefore, these traditional tattoos are thought to derive from pre-Islamic times.[245]

Tattoo ink is made by mixing soot with (breast) milk and the poisonous liquid from the gall bladder of an animal. The design is drawn on the skin using a thin twig and is, by needle, penetrated under the skin. These have a wide variety of meanings and purposes, among which are protection against evil or illnesses; beauty enhancement; and the showing of tribal affiliations. Religious symbolism is also common among both traditional and modern Kurdish tattoos. Tattoos are more prevalent among women than among men, and were generally worn on feet, the chin, foreheads and other places of the body.[245][246]

The popularity of permanent, traditional tattoos has greatly diminished among newer generation of Kurds. However, modern tattoos are becoming more prevalent; and temporary tattoos are still being worn on special occasions (such as henna, the night before a wedding) and as tribute to the cultural heritage.[245]

Music and dance

Traditionally, there are three types of Kurdish classical performers: storytellers (çîrokbêj), minstrels (stranbêj), and bards (dengbêj). No specific music was associated with the Kurdish princely courts. Instead, music performed in night gatherings (şevbihêrk) is considered classical. Several musical forms are found in this genre. Many songs are epic in nature, such as the popular Lawiks, heroic ballads recounting the tales of Kurdish heroes such as Saladin. Heyrans are love ballads usually expressing the melancholy of separation and unfulfilled love, one of the first Kurdish female singers to sing heyrans is Chopy Fatah, while Lawje is a form of religious music and Payizoks are songs performed during the autumn. Love songs, dance music, wedding and other celebratory songs (dîlok/narînk), erotic poetry, and work songs are also popular.

Throughout the Middle East, there are many prominent Kurdish artists. Most famous are Ibrahim Tatlises, Nizamettin Arıç, Ahmet Kaya and the Kamkars. In Europe, well-known artists are Darin Zanyar, Sivan Perwer, and Azad.

Cinema

The main themes of Kurdish films are the poverty and hardship which ordinary Kurds have to endure. The first films featuring Kurdish culture were actually shot in Armenia. Zare, released in 1927, produced by Hamo Beknazarian, details the story of Zare and her love for the shepherd Seydo, and the difficulties the two experience by the hand of the village elder.[247] In 1948 and 1959, two documentaries were made concerning the Yezidi Kurds in Armenia. These were joint Armenian-Kurdish productions; with H. Koçaryan and Heciye Cindi teaming up for The Kurds of Soviet Armenia,[248] and Ereb Samilov and C. Jamharyan for Kurds of Armenia.[248]

The first critically acclaimed and famous Kurdish films were produced by Yılmaz Güney. Initially a popular, award-winning actor in Turkey with the nickname Çirkin Kral (the Ugly King, after his rough looks), he spent the later part of his career producing socio-critical and politically loaded films. Sürü (1979), Yol (1982) and Duvar (1983) are his best-known works, of which the second won Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival of 1982,[249] the most prestigious award in the world of cinema.

Another prominent Kurdish film director is Bahman Qubadi. His first feature film was A Time for Drunken Horses, released in 2000. It was critically acclaimed, and went on to win multiple awards. Other movies of his would follow this example;[250] making him one of the best known film producers of Iran of today. Recently, he released Rhinos Season, starring Behrouz Vossoughi, Monica Bellucci and Yilmaz Erdogan, detailing the tumultuous life of a Kurdish poet.

Other prominent Kurdish film directors are Mahsun Kırmızıgül, Hiner Saleem and before mentioned Yilmaz Erdogan. There’s also been a number of films set and/or filmed in Kurdistan made by non-Kurdish film directors, such as the Wind Will Carry Us, Triage, The Exorcist, The Market: A Tale of Trade, Durchs wilde Kurdistan and Im Reiche des silbernen Löwen.

Sports

The most popular sport among the Kurds is football. Because the Kurds have no independent state, they have no representative team in FIFA or the AFC; however a team representing Iraqi Kurdistan has been active in the Viva World Cup since 2008. They became runners-up in 2009 and 2010, before ultimately becoming champion in 2012.

On a national level, the Kurdish clubs of Iraq have achieved success in recent years as well, winning the Iraqi Premier League four times in the last five years. Prominent clubs are Erbil SC, Duhok SC, Sulaymaniyah FC and Zakho FC.

In Turkey, a Kurd named Celal Ibrahim was one of the founders of Galatasaray S.K. in 1905, as well as one of the original players. The most prominent Kurdish-Turkish club is Diyarbakirspor. In the diaspora, the most successful Kurdish club is Dalkurd FF and the most famous player is Eren Derdiyok.[251]

Another prominent sport is wrestling. In Iranian Wrestling, there are three styles originating from Kurdish regions:

- Zhir-o-Bal (a style similar to Greco-Roman wrestling), practised in Kurdistan, Kermanshah and Ilam;[252]

- Zouran-Patouleh, practised in Kurdistan;[252]

- Zouran-Machkeh, practised in Kurdistan as well.[252]

Furthermore, the most accredited of the traditional Iranian wrestling styles, the Bachoukheh, derives its name from a local Khorasani Kurdish costume in which it is practiced.[252]

Kurdish medalists in the 2012 Summer Olympics were Nur Tatar,[253] Kianoush Rostami and Yezidi Misha Aloyan;[254] who won medals in taekwondo, weightlifting and boxing, respectively.

Architecture

The traditional Kurdish village has simple houses, made of mud. In most cases with flat, wooden roofs, and, if the village is built on the slope of a mountain, the roof on one house makes for the garden of the house one level higher. However, houses with a beehive-like roof, not unlike those in Harran, are also present.

Over the centuries many Kurdish architectural marvels have been erected, with varying styles. Kurdistan boasts many examples from ancient Iranic, Roman, Greek and Semitic origin, most famous of these include Bisotun and Taq-e Bostan in Kermanshah, Takht-e Soleyman near Takab, Mount Nemrud near Adiyaman and the citadels of Erbil and Diyarbakir.

The first genuinely Kurdish examples extant were built in the 11th century. Those earliest examples consist of the Marwanid Dicle Bridge in Diyarbakir, the Shadaddid Minuchir Mosque in Ani,[255] and the Hisn al Akrad near Homs.[256]

In the 12th and 13th centuries the Ayyubid dynasty constructed many buildings throughout the Middle East, being influenced by their predecessors, the Fatimids, and their rivals, the Crusaders, whilst also developing their own techniques.[257] Furthermore, women of the Ayyubid family took a prominent role in the patronage of new constructions.[258] The Ayyubids’ most famous works are the Halil-ur-Rahman Mosque that surrounds the Pool of Sacred Fish in Urfa, the Citadel of Cairo[259] and most parts of the Citadel of Aleppo.[260] Another important piece of Kurdish architectural heritage from the late 12th/early 13th century is the Yezidi pilgrimage site Lalish, with its trademark conical roofs.

In later periods too, Kurdish rulers and their corresponding dynasties and emirates would leave their mark upon the land in the form mosques, castles and bridges, some of which have decayed, or have been (partly) destroyed in an attempt to erase the Kurdish cultural heritage, such as the White Castle of the Bohtan Emirate. Well-known examples are Hosap Castle of the 17th century,[261] Sherwana Castle of the early 18th century, and the Ellwen Bridge of Khanaqin of the 19th century.

Most famous is the Ishak Pasha Palace of Dogubeyazit, a structure with heavy influences from both Anatolian and Iranic architectural traditions. Construction of the Palace began in 1685, led by Colak Abdi Pasha, a Kurdish bey of the Ottoman Empire, but the building wouldn’t be completed until 1784, by his grandson, Ishak Pasha.[262][263] Containing almost 100 rooms, including a mosque, dining rooms, dungeons and being heavily decorated by hewn-out ornaments, this Palace has the reputation as being one of the finest pieces of architecture of the Ottoman Period, and of Anatolia.

In recent years, the KRG has been responsible for the renovation of several historical structures, such as Erbil Citadel and the Mudhafaria Minaret.[264]

Gallery

-

Kurdish man on horseback.

-

Three Kurdish children from Bismil Province, Turkey.

-

Portrait of a Kurdish Peshmerga fighter holding his daughter in their village outside of Dohuk, Iraq

-

Kurdish boy from Beritan tribe

-

Kurdish Girls from Iran, ca. 1840 - 1933.

-

Kurdish girl, 1900

-

Kurdish man from Arbil

-

Kurdish children from Serenli village, Savur district, Turkey.

-

Portrait of a Kurdish cavalryman by Gigo Gabashvili, 1936.

-

A Kurdish woman, by Zoro Mettini.

-

Iraqi Kurdish smugglers near the border of Iraq

-

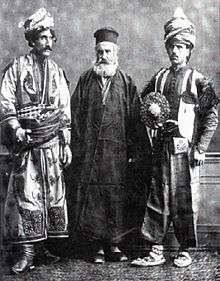

._Auguste_Wahlen._Moeurs%2C_usages_et_costumes_de_tous_les_peuples_du_monde._1843.jpg)

Mercier. Kurde (Asie) by Auguste Wahlen, 1843

See also

- Anatolian Kurds

- History of the Kurdish people

- Iranian Kurdistan

- Iranian languages

- Iranian peoples

- Iraqi Kurdistan

- Khorasani Kurds

- Kurdish Christians

- Kurdish Jews

- Kurds in Georgia

- Kurds in Lebanon

- Kurds in Turkey

- Lak people (Iran)

- List of Kurdish dynasties and countries

- List of Kurdish people

- List of Kurdish organisations

- National symbols of the Kurds

- Origins of the Kurds

- Syrian Kurdistan

- Turkish Kurdistan

- Yazidis

- Zaza people

Modern Kurdish governments

- Kingdom of Kurdistan 1920

- Republic of Ararat 1927–30

- Republic of Mahabad 1946

- Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) (1991 to date)

Notes and references

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 World Factbook (Online ed.). Langley, Virginia: US Central Intelligence Agency. 2015. ISSN 1553-8133. Retrieved 2 August 2015. A rough estimate in this edition has populations of 14.3 million in Turkey, 8.2 million in Iran, about 5.6 to 7.4 million in Iraq, and less than 2 million in Syria, which adds up to approximately 28–30 million Kurds in Kurdistan or adjacient regions. CIA estimates are as of August 2015 – Turkey: Kurdish 18%, of 81.6 million; Iran: Kurd 10%, of 81.82 million; Iraq: Kurdish 15%-20%, of 37.01 million, Syria: Kurds, Armenians, and other 9.7%, of 17.01 million.

- 1 2 3 Mackey, Sandra (2002). The Reckoning: Iraq and the Legacy of Saddam. W.W. Norton and Co. p. 350.

As much as 25% of Turkey is Kurdish

This would raise the population estimate by about 5 million. - ↑ "Over 22.5 million Kurds live in Turkey, new Turkish statistics reveal". Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Yildiz, Kerim; Fryer, Georgina (2004). The Kurds: Culture and Language Rights. Kurdish Human Rights Project. Data: 18% of Turkey, 20% of Iraq, 8% of Iran, 9.6%+ of Syria; plus 1–2 million in neighboring countries and the diaspora

- ↑ Ağirdir, Bekir (21 December 2008). "Kürtlerin nüfusu 11 milyonda İstanbul"da 2 milyon Kürt yaşıyor – Radikal Dizi". Radikal.com.tr (in Turkish). Retrieved 2013-07-12.

- ↑ Volume 2. Dabbagh – Kuwait University. — Iran, page 1111–1112. // Encyclopedia of Modern Middle East & North Africa. Second Edition. Volume 1 — 4. Editor in Chief: Philip Mattar. Associate Editors: Charles E. Butterworth, Neil Caplan, Michael R. Fischbach, Eric Hooglund, Laurie King–Irani, John Ruedy. Farmington Hills: Gale, 2004, 2936 pages. ISBN 9780028657691 "With an estimated population of 67 million in 2004, Iran is one of the most populous countries in the Middle East. ... Iran’s second largest ethnolinguistic minority, the Kurds, make up an estimated 5 percent of the country’s population and reside in the provinces of Kerman and Kurdistan as well as in parts of West Azerbaijan and Ilam. Kurds in Iran are divided along religious lines as Sunni, Shi'ite, or Ahl-e Haqq."

- ↑ Hoare, Ben; Parrish, Margaret, eds. (1 March 2010). "Country Factfiles — Iran". Atlas A–Z (Fourth ed.). London: Dorling Kindersley Publishing. p. 238. ISBN 9780756658625.

poem stripmarker inPopulation: 74.2 million

Religions: Shi'a Muslim 93%, Sunni Muslim 6%, other 1%

Ethnic Mix: Persian 50%, Azari 24%, other 10%, Kurd 8%, Lur and Bakhtiari 8%|quote=at position 1 (help) - ↑ Hoare & Parrish, ed. (2010). "Country Factfiles — Iran". Atlas A–Z (4th ed.). p. 239.

poem stripmarker inPopulation: 30.7 million

Religions: Shi'a Muslim 60%, Sunni Muslim 35%, other 5%

Ethnic Mix: Arab 80%, Kurd 15%, Turkmen 3%, other 2%|quote=at position 1 (help) - ↑ Dabrowska, Karen; Hann, Geoff (2008). "Ethnic groups and languages". Iraq Then and Now: A Guide to the Country and Its People. Chalfont St Peter, UK: Bradt Travel Guides. pp. 12–13. ISBN 9781841622439.

The Iraqi people were once like a necklace, where the thread of nationality united a variety of unique and colourful beads. The Arabs are in the majority, making up at least 75% of the population, while 18% are Kurds and the remaining 7% consists of Assyrians, Turcomans, Armenians and other, smaller minorities

This is a tertiary source that clearly includes information from other sources but does not name them. - ↑ "Iraq". The World Factbook. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ↑ Hoare & Parrish, ed. (2010). "Country Factfiles — Syria". Atlas A–Z (4th ed.). p. 331.

poem stripmarker inPopulation: 21.9 million

Religions: Sunni Muslim 74%, other Muslim 16%, Christian 10%

Ethnic Mix: Arab 89%, Kurd 6%, other 3%, Armenian, Turkmen, Circassian 2%|quote=at position 1 (help) - ↑ Jacobs Sparks, Karen, ed. (2011). "World Data — Syria". Britannica Book of the Year 2010. Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. p. 709. ISBN 9781615353668.

poem stripmarker inPopulation (2009): 21,763,000 (Includes 1,200,000 Iraqi refugees and 450,000 long-term Palestinian refugees in mid-2009.)

Ethnic composition (2000): Syrian Arab 74.9%; Bedouin Arab 7.4%; Kurd 7.3%; Palestinian Arab 3.9%; Armenian 2.7%; other 3.8%.

Religious affiliation (2000): Muslim c. 86%, of which Sunni c. 74%, Alawite (Shi'i) c. 11%; Christian c. 8%, of which Orthodox c. 5%, Roman Catholicc. 2%; Druze c. 3%; nonreligious/atheist c. 3%.|quote=at position 1 (help) - ↑ Van Bruinessen, Martin (1992). "General Information on Kurdistan — Population". Agha, Shaikh and State: The Social and Political Structures of Kurdistan. London: Zed Books. p. 15. ISBN 9781856490184.

Syria Here too, divergent estimates are made, but most fluctuate around 8.5% of the population, or just over 600,000 in 1975.

- ↑ McDowall, David (2004). "Appendix 2. The Kurds of Syria". A Modern History of the Kurds (Third ed.). London: I.B. Tauris. p. 466. ISBN 9781850434160.

Kurds probably constitute between 8 and 10 percent of the population of modern Syria, probably 1.2 and 1.5 million out of total population of an estimated 15.3 million in 1998.

- ↑ Lowe, Robert. "Studying the Kurds in Syria: Challenges and Opportunities". Syrian Studies Association Bulletin. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ↑ Henriques, John L. Syria: Issues and Historical Background. Nova Science Publishers. ISBN 9781590337639.

- ↑ Khasraw Gul, Zana (22 July 2013). "Where are the Syrian Kurds heading amidst the civil war in Syria?". openDemocracy.net. openDemocracy. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ↑ "Syria". Central Intelligence Agency. May 2015. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ↑ "Syria Overview". Minority Rights Group International. October 2011. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ↑ "Information from the 2011 Armenian National Census" (PDF). Statistics of Armenia (in Armenian). Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ↑ "The Human Rights situation of the Yezidi minority in the Transcaucasus" (PDF). United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. p. 18.

- ↑ Statistical Yearbook of Azerbaijan 2014. 2015. p. 80. Bakı.

- ↑ "Camps built in Germany, Austria to win new members for PKK, reports reveal". Zaman. 9 August 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ↑ "3 Kurdish women political activists shot dead in Paris". CNN. 11 January 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ↑ "Sweden". Ethnologue. 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ↑ "The Kurdish Diaspora". Institut Kurde de Paris. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ↑ "Kurds in Netherlands". WereldJournalisten.nl. 23 May 2007. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ↑ "Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 г. Национальный состав населения Российской Федерации". Demoscope.ru. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ↑ "QS211EW – Ethnic group (detailed)". NOMISweb.co.uk. UK Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ↑ "Ethnic Group – Full Detail_QS201NI". Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ↑ "Scotland's Census 2011 – National Records of Scotland, Language used at home other than English (detailed)" (PDF). scotlandscensus.gov.uk. Scotland Census. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ↑ Численность населения Республики Казахстан по отдельным этносам на начало 2014 года ЭТНОДЕМОГРАФИЧЕСКИЙ ЕЖЕГОДНИК КАЗАХСТАНА 2014

- ↑ "Switzerland". Ethnologue. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ↑ "Fakta: Kurdere i Danmark". Jyllandsposten (in Danish). 8 May 2006. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ↑ Al-Khatib, Mahmoud A.; Al-Ali, Mohammed N. "Language and Cultural Shift Among the Kurds of Jordan" (PDF). p. 12. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ↑ "Austria". Ethnologue. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ↑ "Greece". Ethnologue. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- 1 2 "2006–2010 American Community Survey Selected Population Tables". FactFinder2.Census.gov. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ↑ "Number of resident population by selected nationality" (PDF). UNStats.UN.org. United Nations. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ↑ "Население Кыргызстана" (in Russian). Archived from the original on 15 September 2012.

- 1 2 "2011 National Household Survey: Data tables". StatCan.GC.ca. Statistics Canada. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ "Language according to age and sex by region 1990–2014". Stat.fi. Statistics Finland. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ The People of Australia: Statistics from the 2011 census (PDF). Australian Department of Immigration and Border Protection. 2014. ISBN 978-1-920996-23-9. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ↑ Kurdish Awakening: Nation Building in a Fragmented Homeland, (2014), by Ofra Bengio, University of Texas Press

- 1 2 John A. Shoup III (17 October 2011). Ethnic Groups of Africa and the Middle East: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 159. ISBN 978-1-59884-363-7.

- 1 2 McDowall, David (14 May 2004). A Modern History of the Kurds (Third ed.). I.B. Tauris. pp. 8–9, 373, 375. ISBN 978-1-85043-416-0.

- ↑ "Kurds". The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed. Encyclopedia.com. 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ↑ Izady, Mehrdad R. (1992). The Kurds: A Concise Handbook. Taylor & Francis. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-8448-1727-9.

- ↑ Bois, T.; Minorsky, V.; MacKenzie, D. N. (2009). "Kurds, Kurdistan". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, T.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. Encyclopaedia Islamica. Brill.

poem stripmarker inThe Kurds, an Iranian people of the Near East, live at the junction of more or less laicised Turkey". ...

We thus find that about the period of the Arab conquest a single ethnic term Kurd (plur. Akrād) was beginning to be applied to an amalgamation of Iranian or iranicised tribes. ...

The classification of the Kurds among the Iranian nations is based mainly on linguistic and historical data and does not prejudice the fact there is a complexity of ethnical elements incorporated in them.|quote=at position 1 (help) - ↑ David Romano (2 March 2006). The Kurdish Nationalist Movement: Opportunity, Mobilization and Identity. Cambridge University Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-521-85041-4.

- ↑ Barbara A. West (1 January 2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. p. 518. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7.

- ↑ Ofra Bengio (15 November 2014). Kurdish Awakening: Nation Building in a Fragmented Homeland. University of Texas Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-292-75813-1.

- 1 2 3 Paul, Ludwig (2008). "Kurdish Language". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 2 December 2011. Writes about the problem of attaining a coherent definition of "Kurdish language" within the Northwestern Iranian dialect continuum. There is no unambiguous evolution of Kurdish from Middle Iranian, as "from Old and Middle Iranian times, no predecessors of the Kurdish language are yet known; the extant Kurdish texts may be traced back to no earlier than the 16th century CE." Ludwig Paul further states: "Linguistics itself, or dialectology, does not provide any general or straightforward definition of at which point a language becomes a dialect (or vice versa). To attain a fuller understanding of the difficulties and questions that are raised by the issue of the 'Kurdish language,' it is therefore necessary to consider also non-linguistic factors."

- ↑ D. N. MacKenzie (1961). "The Origins of Kurdish". Transactions of the Philological Society: 68–86.

- ↑ Based on arithmetic from World Factbook and other sources cited herein: A Near Eastern population of 28–30 million, plus approximately 2 million diaspora gives 30–32 million. If the highest (25%) estimate for the Kurdish population of Turkey, in Mackey (2002), proved correct, this would raise the total to around 37 million.

- ↑ Asatrian, G. (2009). Prolegomena to the Study of the Kurds, Iran and the Caucasus 13. pp. 1–58.