Konbaung–Hanthawaddy War

| Konbaung–Hanthawaddy War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Wars of Konbaung Empire | |||||||

Konbaung invasion of Lower Burma 1755–1757 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Restored Hanthawaddy Kingdom | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Binnya Dala Upayaza Talaban Toungoo Ngwegunhmu | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

~5000 (1752) 20,000[1] (1753) 30,000+ (1754–1757)[2] |

10,000 (1752)[3] ~7,000 (1753) 20,000 (1754–1757) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| unknown but probably higher than Hanthawaddy[4] | unknown | ||||||

The Konbaung–Hanthawaddy War (Burmese: ကုန်းဘောင်-ဟံသာဝတီ စစ်) was the war fought between the Konbaung Dynasty and the Restored Hanthawaddy Kingdom of Burma (Myanmar) from 1752 to 1757. The war was the last of several wars between the Burmese-speaking north and the Mon-speaking south that ended the Mon people's centuries-long dominance of the south.[5][6]

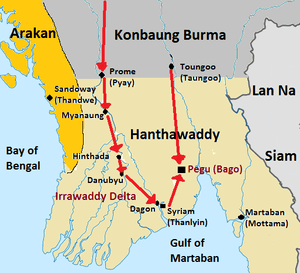

The war began in April 1752 as independent resistance movements against Hanthawaddy armies which had just toppled the Toungoo Dynasty. Alaungpaya, who founded the Konbaung Dynasty, quickly emerged as the main resistance leader, and by taking advantage of Hanthawaddy's low troop levels, went on to conquer all of Upper Burma by the end of 1753. Hanthawaddy belatedly launched a full invasion in 1754 but it faltered. The war increasingly turned ethnic in character between the Burman (Bamar) north and the Mon south. Konbaung forces invaded Lower Burma in January 1755, capturing the Irrawaddy delta and Dagon (Yangon) by May. The French defended port city of Syriam (Thanlyin) held out for another 14 months but eventually fell in July 1756, ending French involvement in the war. The fall of the 16-year-old southern kingdom soon followed in May 1757 when its capital Pegu (Bago) was sacked. Disorganized Mon resistance fell back to the Tenasserim peninsula (present day Mon State and Taninthayi Region) in the next few years with Siamese help but was driven out by 1765 when Konbaung armies captured the peninsula from the Siamese.

The war proved decisive. Ethnic Burman families from the north began settling in the delta after the war. By the early 19th century, assimilation and inter-marriage had reduced the Mon population to a small minority.[5]

Background

The authority of Toungoo Dynasty with the capital at Ava (Inwa) had long been in decline when the Mon of Lower Burma broke away in 1740, and founded the Restored Hanthawaddy Kingdom with the capital at Pegu (Bago). The "palace kings" at Ava had been unable to defend against the Manipuri raids, which began in 1724 and had been ransacking increasingly deeper parts of Upper Burma. Ava failed to recover southern Lan Na (Chiang Mai) that revolted in 1727, and did nothing to prevent the annexation of northern Shan states by Qing China in the mid-1730s. King Mahadhammaraza Dipadi of Toungoo made feeble efforts to recover Lower Burma in the early 1740s, but by 1745, Hanthawaddy had successfully established itself in Lower Burma.

The low-grade warfare between Ava and Pegu went on until late 1750, when Pegu launched its final assault, invading Upper Burma in full force. By early 1752, Peguan forces, equipped with French arms, had reached the gates of Ava. Upayaza, the heir apparent of Hanthawaddy throne, issued a proclamation, summoning the administrative officers in the country north of the city to submit, and swear allegiance to the king of Hanthawaddy. Many regional chiefs of Upper Burma faced a choice: whether to join the Hanthawaddy forces or resist occupation. A few chose to cooperate. But many others chose to resist.[7]

Upper Burma (1752–1754)

By late March 1752, it was clear to everyone that Ava's fate was sealed. Hanthawaddy forces had breached Ava's outer defenses, and pushed Avan defenses inside the palace walls. At Moksobo in the Mu valley about 60 miles northwest of Ava, one village headman named Aung Zeya persuaded 46 villages in home region to join him in resistance. Aung Zeya proclaimed himself king with the royal style of Alaungpaya (the Embryo Buddha), and founded the Konbaung Dynasty. He prepared the defenses by stockading his village, now renamed Shwebo, and building a moat around it. He had the jungle outside the stockade cleared, the ponds destroyed and the wells filled.

Konbaung was only one among many other resistance forces, at Salin along the middle Irrawaddy and Mogaung in the far north, which had independently sprung up across panicked Upper Burma. Fortunately for the resistance forces, the Hanthawaddy command mistakenly equated their capture of Ava with the victory over Upper Burma, and withdrew two-thirds of the invasion force back to Pegu, leaving just a third (less than 10,000 men)[3] for what they considered a mop-up operation. Moreover, the Hanthawaddy leadership was concerned by the Siamese annexation of the upper Tenasserim peninsula (present-day Mon State) while Hanthawaddy troops were laying siege to Ava.[8][9]

The decision to redeploy turned out to be an epic miscalculation as the Siamese threat was never as acute as the threat from Upper Burma, the traditional home of political power in Burma. The Siamese takeover of Upper Tenasserim was an opportunistic land grab taking advantage of Hanthawaddy's preoccupations with Ava. It is unclear whether the Siamese ever planned or had the means to extend their influence into mainland Lower Burma. It was much more probable that any existential threat to Hanthawaddy would come from Upper Burma.

Battle of Shwebo (1752)

The Hanthawaddy command nevertheless was confident that they could pacify the entire Upper Burma countryside. At first the strategy seemed to work. They established outposts as far north as Wuntho and Kawlin in present day northern Sagaing Region, and the Gwe Shans of Madaya in present-day northern Mandalay Region joined them. The Hanthawaddy officer stationed at Singu, about 30 miles north of Ava, sent a detachment of 50 men to secure allegiance of the Mu valley.[3] Alaungpaya personally led forty of his best men to meet the detachment at Halin, south of Shwebo, and wiped them out. It was 20 April 1752 (Thursday, 4th waxing of Kason 1114 ME).[10]

As Upayaza prepared to ship the main body of his troops downstream, leaving a garrison behind under his next-in-command, Talaban. Before leaving he received the unpleasant news that one of his detachments, sent to demand the allegiance of Moksobo had been cut to pieces by the inhabitants. He ought to have enquired more carefully into the nature of the incident, but made the fatal mistake of treating it as trivial. With the parting injunction to Talaban to make an example of the place, he set off home with his troops.[9]

Another larger detachment was sent. It too was defeated, with only half a dozen got back to Ava alive. In May, Gen. Talaban himself led a force of several thousand well-armed troops to take Shwebo. But the army lacked cannon to overcome the stockade, and it was forced to lay siege. A month into the siege, on 20 June 1752,[11] Alaungpaya burst out at the head of a general sortie and routed the besiegers. The Hanthawaddy forces withdrew in disarray, leaving their equipment, including several scores of muskets, which were "worth their weight in gold in these critical days".[12]

Consolidation of Upper Burma (1752–1753)

The news spread. Soon, Alaungpaya was mustering a proper army from across the Mu valley and beyond, using his family connections and appointing his fellow gentry leaders as his key lieutenants. Success drew fresh recruits everyday from many regions across Upper Burma. Alaungpaya then selected 68 ablest men to be the commanders of his growing army. Many of the 68 would prove to be brilliant military commanders in Konbaung's domestic and external campaigns, and form the core leadership of Konbaung armies for the next thirty years. They include the likes of Minhla Minkhaung Kyaw, Minkhaung Nawrahta, Maha Thiha Thura, Ne Myo Sithu, Maha Sithu and Balamindin. Most other resistance forces as well as officers from the disbanded Palace Guards had joined him with such arms as they retained. By October 1752, he had emerged the primary challenger to Hanthawaddy, and driven out all Hanthawaddy outposts north of Ava, and their allies Gwe Shans from Madaya. He also defeated a rival resistance leader, Chit Nyo of Khin-U. A dozen legends gathered around his name. Men felt that when he led them they could not fail.[12]

Despite repeated setbacks, Pegu incredibly still did not send in reinforcements even as Alaungpaya consolidated his gains throughout Upper Burma. Instead of sending every troop they had, they merely replaced Talaban, the general who won Ava, with another general, Toungoo Ngwegunhmu. By late 1753, Konbaung forces controlled all of Upper Burma except Ava. On 3 January 1754, Alaungpaya's second son, Hsinbyushin, only 17, successfully retook Ava, which was left ruined and burned.[13] The whole of Upper Burma was clear of Hanthawaddy troops. Alaungpaya then turned to nearer Shan States to secure the rear, and to draw fresh levies. He received homage from the nearer sawbwas (saophas or chiefs) as far north as Momeik.[14]

_Myanmar(Burma).jpg)

Hanthawaddy counter-offensive (1754)

In March 1754, Hanthawaddy did what they should have done two years before, and sent the entire army. It would have been 1751–1752 all over again except that they had to face Alaungpaya instead of an effete dynasty. At first, the invasion went as planned. The Hanthawaddy forces led by Upayaza, the heir-apparent and Gen. Talaban defeated the Konbaung armies led by Alaungpaya's sons Naungdawgyi and Hsinbyushin at Myingyan. One Hanthawaddy army chased Hsinbyushin to Ava, and laid siege to the city. Another army chased Naungdawgyi's army, advancing as far as Kyaukmyaung a few miles from Shwebo, where Alaungpaya was residing. The Hanthawaddy flotilla had complete control of the entire Irrawaddy River.

But they could not make further progress. They met heavy Konbaung resistance at Kyaukmyaung, and lost many men trying to take a heavily fortified Ava. Two months into the invasion, the invasion was going nowhere. The Hanthawaddy forces had lost many men and boats, and were short on ammunition and supplies. In May, Alaungpaya personally led his armies (10,000 men, 1000 cavalry, 100 elephants) in the Konbaung counterattack, and pushed back the invaders to Sagaing, on the west bank of the Irrawaddy, opposite Ava. On the east bank, Hsinbyushin also broke the siege of Ava. With the rainy season just a few weeks away, the Hanthawaddy command decided to retreat.[15]

Meanwhile, Burman refugees who had escaped general slaughter by the delta Mons seized Prome (Pyay), the historical border town between Upper Burma and Lower Burma, and shut the gates to the retreating Hanthawaddy armies. Knowing the importance of Prome for the safety of his kingdom, King Binnya Dala of Hanthawaddy ordered his forces to retake Prome at any cost. Led by Talaban, the Hanthawady forces consisted of 10,000 men and 200 war boats laid siege to Prome.[16]

Turning into an ethnic conflict

By late 1754, the siege of Prome was going nowhere for Talaban's men. The besiegers had been able to fight off Konbaung attempts to lift the siege but they could not take the fortified city either. At Pegu, some of the Hanthawaddy commanders now feared Alaungpaya's full-scale invasion of the south, and looked for an alternative. Preferring the loose rule of a weak king, they attempted to free the captive king, Mahadhammaraza Dipati on the throne of Hanthawaddy. The plot was discovered by Binnya Dala, who executed not only the conspirators but also the former king himself and other captives from Ava in October 1754. This shortsighted action removed the only possible rival to Alaungpaya, and allowed those who had stayed loyal to the former king to join Alaungpaya with an easy conscience.[17]

The conflict increasingly turned into an ethnic conflict between the Burman north and the Mon south. It was not always so. When the southern rebellion began in 1740, the Mon leaders of the rebellion welcomed southern Burmans and Karens who despised Ava's rule. The first king of Restored Hanthawaddy, Smim Htaw Buddhaketi, despite his Mon title, was an ethnic Burman. Burmans of the south had served in the Mon-speaking Hanthawaddy army although there had been episodes of purges of Burmans throughout the south by their Mon compatriots since 1740. (About 8000 ethnic Burmans were massacred in 1740.) Instead of persuading their Burman troops to stay, when they needed every last soldier, the Hanthawaddy leadership escalated "self-defeating" policies of ethnic polarization. They began requiring all Burmans in the south to wear an earring with a stamp of the Pegu heir-apparent and to cut their hair in Mon fashion as a sign of loyalty.[5] This persecution strengthened Alaungpaya's hand. Alaungpaya was only happy to exploit the situation, encouraging remaining Burman troops to come over to him. Many did.

Konbaung invasion of Lower Burma (1755–1757)

While the Hanthawaddy leadership alienated their Burman constituency in the south, Alaungpaya gathered troops from all over Upper Burma, including Shan, Kachin and Chin levies. By January 1755, he was ready to launch a full-scale invasion of the south. The invading army now had a considerable manpower advantage. Hanthawaddy troops still had better firearms and modern weaponry. (Hanthawaddy's firearm advantage would claim many Konbaung casualties in upcoming battles.)

Battle of Prome (June 1754 – February 1755)

Alaungpaya's first target was Prome that had been under siege by the Hanthawaddy troops for seven months. The Hanthawaddy troops were well entrenched in their earthwork stockades surrounding Prome. They had repulsed Konbaung troops trying to relieve the siege throughout 1754. In January, Alaungpaya himself returned with a large army. Still, Konbaung assaults could not make any headway amid heavy musket fire by determined Hanthawaddy defenses. Alaungpaya then ordered large 6-foot (2 m) by 30-foot (9 m) basket cases filled with hay, which were to be used as cover. Then in mid-February, the Konbaung troops forced their way in behind rolling baskets amid heavy slaughter by musket fire, and captured the Mayanbin fort, relieving the siege.[18] They captured many muskets, cannon and ammunition, which Hanthawaddy had acquired from Europeans at Thanlyin, along with 5000 prisoners of war. The Hanthawaddy troops retreated to the delta. Alaungpaya entered Prome, returned solemn thanks at the Shwesandaw Pagoda, and received homage of central Burma. He held an investiture, honoring those who had led the uprising against Hanthawaddy.[14][19]

Battle of Irrawaddy delta (April–May 1755)

In early April, he launched the invasion of Irrawaddy delta in a blitz. He occupied Lunhse, renaming it Myanaung (Speedy Victory). Moving down the river, the advance guard defeated the Hanthawaddy resistance at Hinthada, and captured Danubyu by mid-April, right before the Burmese new year festivities. By late April, his forces had overrun the entire delta.[19] Alaungpaya now received homage from local lords, as far away as Thandwe in Arakan (Rakhine).[14]

Then the Konbaung armies turned their sights on the main port city of Syriam (Thanlyin), which stood in their way to Pegu. On 5 May 1755, Konbaung troops defeated a Hanthawaddy division at Dagon, on the opposite bank of Syriam. Alaungpaya envisioned Dagon to be the future port city, added settlements around Dagon, and renamed the new city, Yangon (lit. "End of Strife").[19]

Battle of Syriam (May 1755 – July 1756)

The fortified port of Syriam was guarded by Hanthawaddy troops, aided by the French personnel and arms. Konbaung armies' first attempt to take the city in May 1755 was a failure. Its sturdy walls and modern cannon made difficult any attempt to storm the fortress. In June, Hanthawaddy launched a counter-offensive, attacking the Konbaung stronghold at Yangon. The attack was joined in by an English East India Company ship Arcot, apparently without orders by the Company. The counterattack was unsuccessful. The English, fearing reprisals by Alaungpaya, now speedily sent an envoy, Captain George Baker, to Alaungpaya at Shwebo with presents of cannon and muskets and with orders to conclude a friendship.[20]

Although Alaungpaya was deeply suspicious of English intentions, he also needed to secure modern arms against French-defended Syriam. He agreed that the English could stay at their colony at Negrais, which they had seized since 1753, but postponed signing any immediate treaty with the Company. Instead, he proposed an alliance between the two countries. The English who were about to enter the Seven Years' War against the French seemed like natural allies. Despite what Alaungpaya regarded as a magnanimous gesture over Negrais no military help of any kind materialized.[20]

Konbaung troops would now have to take Syriam the hard way. The siege continued for the remainder of 1755. The French inside were desperate for reinforcements from their India headquarters at Pondicherry. Alaungpaya returned to the front in January 1756 with his two sons, Naungdawgyi and Hsinbyushin. In July, Alaungpaya launched another attack by water and by land, capturing the only French ship left at the port, and the French factory at the outskirts of the town. On 14 July 1756 (3rd waning of Waso 1118 ME),[21] Minhla Minkhaung Kyaw, the chief of musket corps and top Konbaung general, was severely wounded by cannon fire. As Minhla Minkhaung Kyaw lay dying of his wounds, and being brought back by boat, the king went down to the boat himself to see his old childhood friend, who had won him many battles. The king publicly mourned the death of his chief general and honored him with a funeral under a white umbrella before the whole army.[22][23] The leader of the French, Sieur de Bruno, secretly tried to negotiate with Alaungpaya, but was found out and put in prison by Hanthawaddy commanders. The siege went on.

For Alaungpaya, the worry was that French reinforcements would soon arrive. He decided that the time had come for the fortress to be stormed, now. He knew that the French and the Mons, expecting no quarter, would resist fiercely and that hundreds of his men would die in any attempt to breach the walls. He called for volunteers and then selected 93, whom he named the Golden Company of Syriam, a name that would find pride of place in Burmese nationalist mythology. They included guards, officers, and royal descendants of Bayinnaung. The afternoon before, as the early monsoon rains poured down in torrents outside the makeshift huts, they ate together in their king's presence. Alaungpaya gave each a leather helmet and lacquer armor.[20]

That evening, on 25 July 1756, as the Konbaung troops banged their drums and played loud music to encourage Syriam's defenders into thinking festivities were under way and to relax their watch, the Golden Company scaled the walls. At the dawn of 26 July 1756, after bloody hand-to-hand fighting they managed to pry open the great wooden gates, and in darkness, amid the war cries of the Konbaung troops ("Shwebotha!" "Shwebotha!"; lit. sons of Shwebo) and the screams of the women and the children inside, the city was overrun. The Hanthawaddy commander barely escaped the carnage. Alaungpaya presented the stacks of gold and silver captured from the city to the surviving 20 men of the Golden Company and the families of the 73 who died.[20][24]

A few days later and a few days too late, on 29 July 1756, two French relief ships, the Galatee and the Fleury arrived, loaded with troops as well as arms, ammunition and food from Pondicherry. The Burmese seized the ships, and press-ganged 200 French officers and soldiers into Alaungpaya's army. Also on board were 35 ship's guns, five field guns and 1300 muskets. It was a considerable haul.[24] More importantly, the battle ended French involvement in the Burmese civil war.

Battle of Pegu (October 1756 – May 1757)

After the fall of Syriam, Alaungpaya waited out the monsoon season. In September, one Konbaung army marched from Syriam in the south, while another army marched from Toungoo (Taungoo) in the north. The advance was slow with great losses as the Hanthawaddy defenses still had cannon and they were literally fighting with their backs to the wall. By mid-October, the combined armies converged on Pegu. Konbaung war boats too flung off Hanthawaddy fire-rafts and completed the Konbaung line around the city.

By January 1757, the city was starving, and Binnya Dala asked for terms. Alaungpaya demanded no less than a full unconditional surrender. Those surrounding Binnya Dala were determined to fight on, and put the king under restraint. The famine only grew worse. On 6 May 1757 (4th waning of Kason 1119)[25] Konbaung armies unleashed their final assault on the starving city. The Konbaung armies broke through at moonrise, and massacred men, women, and children without distinction. Alaungpaya entered through the Mohnyin Gate, surrounded by a crowd of his guardsmen and French gunners, and prostrated himself before the Shwemawdaw Pagoda. The city walls and 20 gates by Tabinshwehti and Bayinnaung two centuries before were then razed to the ground. After the fall of Pegu, the governors of Martaban (Mottama), and Tavoy (Dawei) who had sought Siamese protection, now backtracked and sent in tribute to Alaungpaya.[26][27]

Aftermath

After the fall of Pegu, remnants of Mon resistance fell back to the upper Tenasserim peninsula (present-day Mon State), and remained active there with Siamese support. However, the resistance was disorganized, and did not control any major towns. It remained active only because Konbaung's control of the upper Tenasserim peninsula in 1757–1759 was still largely nominal. Its effective control still did not extend beyond Martaban as the majority of the Konbaung armies were back north in Manipur and in the northern Shan states.[28][29]

However, no single southern leader emerged to rally the Mon populace as Alaungpaya did with the Burmans in 1752. A rebellion broke out in 1758 throughout Lower Burma but was put down by local Konbaung garrisons. The window of opportunity came to a close in the second half of 1759 when the Konbaung armies, having conquered Manipur and the northern Shan states, were back down south, preparing for their invasion of the Tenasserim coast and Siam. The Konbaung armies seized the upper Tenasserim coast following the Burmese-Siamese War (1759–1760), and pushed out the Mon resistance farther down the coast. (Alaungpaya died in the war.) The resistance was driven out of Tenasserim in 1765 when Alaungpaya's son Hsinbyushin seized the lower coastline as part of the Burmese-Siamese War (1765–1767).

Legacy

The Konbaung–Hanthawaddy war was the last of the many wars fought between the Burmese-speaking north and the Mon-speaking south that began with King Anawrahta's conquest of the south in 1057. Many more wars had been fought over the centuries. Aside from the Forty Years' War in the 14th and 15th centuries, the south usually had been on the losing side.

But this war proved to be the proverbial final nail. For the Mon, the defeat marked the end of their dream of independence. For a long time, they would remember the utter devastation that accompanied the final collapse of their short-lived kingdom. Thousands fled across the border into Siam. One Mon monk wrote of the time: "Sons could not find their mothers, nor mothers their sons, and there was weeping throughout the land".[6]

Soon, entire communities of ethnic Burmans from the north began to settle in the delta. Mon rebellions still flared up in 1762, 1774, 1783, 1792, and 1824–1826. Each revolt typically was followed by fresh deportations, Mon flight to Siam, and punitive cultural proscriptions. The last king of Hanthawaddy was publicly humiliated and executed in 1774. In the aftermath of revolts, Burmese language was encouraged at the expense of Mon. Chronicles by late 18th century and early 19th Mon monks portrayed the south's recent history as a tale of unrelenting northern encroachment. By the early 19th century, assimilation and inter-marriage had reduced the Mon population to a small minority. Centuries of Mon supremacy along the coast came to an end.[5][6]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Alaungpaya Ayedawbon 1961: 41–42

- ↑ Alaungpaya Ayedawbon 1961: 77–79

- 1 2 3 Phayre 1967: 150–151

- ↑ Konbaung forces on the offense suffered heavy casualties in battles of Prome, Syriam and Pegu.

- 1 2 3 4 Lieberman 2003: 202–206

- 1 2 3 Myint-U 2006: 97–98

- ↑ Phayre 1967: 149

- ↑ Ba Pe 1952: 145–146

- 1 2 Hall 1960 Chapter IX: Mon Revolt: 15

- ↑ Maung Maung Tin Vol. 1 1905: 53

- ↑ Phayre 1967: 152

- 1 2 Harvey 1925: 220–221

- ↑ Hall 1960: 17, Aung-Thwin 1996: 79 for the exact date

- 1 2 3 Harvey 1925: 222–224

- ↑ Kyaw Thet 1962: 278

- ↑ Phayre 1967: 155

- ↑ Htin Aung 1967: 162–163

- ↑ Kyaw Thet 1962: 282

- 1 2 3 Phayre 1967: 156–158

- 1 2 3 4 Myint-U 2006: 94–95

- ↑ Maung Maung Tin Vol. 1 1905: 153

- ↑ Alaungpaya Ayedawbon 1961: 96

- ↑ Harvey 1925: 236

- 1 2 Maung Maung Tin Vol. 1 (1905): 155–157

- ↑ Maung Maung Tin Vol. 1 (1905): 128

- ↑ Harvey 1925: 241

- ↑ Kyaw Thet 1962: 289

- ↑ Myint-U 2006: 100–101

- ↑ Harvey 1925: 238–239

References

- Aung-Thwin, Michael A. (1996). "Kingdom of Bagan". In Gillian Cribbs. Myanmar Land of the Spirits. Guernsey: Co & Bear Productions. ISBN 0-9527665-0-7.

- Ba Pe (1952). Abridged History of Burma (in Burmese) (9th (1963) ed.). Sarpay Beikman.

- Charney, Michael W. (2006). Powerful Learning: Buddhist Literati and the Throne in Burma's Last Dynasty, 1752-1885. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan.

- Hall, D.G.E. (1960). Burma (3rd ed.). Hutchinson University Library. ISBN 978-1-4067-3503-1.

- Harvey, G. E. (1925). History of Burma: From the Earliest Times to 10 March 1824. London: Frank Cass.

- Htin Aung, Maung (1967). A History of Burma. Cambridge University Press.

- Kyaw Thet (1962). History of Union of Burma (in Burmese). Yangon University Press.

- Letwe Nawrahta and Twinthin Taikwun (c. 1770). Hla Thamein, ed. Alaungpaya Ayedawbon (in Burmese) (1961 ed.). Ministry of Culture, Union of Burma.

- Maung Maung Tin, U (1905). Konbaung Set Maha Yazawin (in Burmese) 1–2 (2004 ed.). Yangon: Department of Universities History Research, University of Yangon.

- Myint-U, Thant (2006). The River of Lost Footsteps--Histories of Burma. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-16342-6.

- Phayre, Lt. Gen. Sir Arthur P. (1883). History of Burma (1967 ed.). London: Susil Gupta.