Conductivity (electrolytic)

Conductivity (or specific conductance) of an electrolyte solution is a measure of its ability to conduct electricity. The SI unit of conductivity is siemens per meter (S/m).

Conductivity measurements are used routinely in many industrial and environmental applications as a fast, inexpensive and reliable way of measuring the ionic content in a solution.[1] For example, the measurement of product conductivity is a typical way to monitor and continuously trend the performance of water purification systems.

In many cases, conductivity is linked directly to the total dissolved solids (T.D.S.). High quality deionized water has a conductivity of about 5.5 μS/m, typical drinking water in the range of 5-50 mS/m, while sea water about 5 S/m[2] (i.e., sea water's conductivity is one million times higher than that of deionized water).

Conductivity is traditionally determined by measuring the AC resistance of the solution between two electrodes. Dilute solutions follow Kohlrausch's Laws of concentration dependence and additivity of ionic contributions. Lars Onsager gave a theoretical explanation of Kohlrausch's law by extending Debye–Hückel theory.

Units

The SI unit of conductivity is S/m and, unless otherwise qualified, it refers to 25 °C. Often encountered in industry is the traditional unit of μS/cm. 106 μS/cm = 103 mS/cm = 1 S/cm. The values in μS/cm are lower than those in μS/m by a factor of 100 (i.e., 1 μS/cm = 100 μS/m). Occasionally a unit of EC (electrical conductivity) is found on scales of instruments: 1 EC = 1 μS/cm.[3] Sometimes encountered is mho (reciprocal of ohm): 1 mho/m = 1 S/m. Historically, mhos antedate Siemens by many decades; good vacuum-tube testers, for instance, gave transconductance readings in micromhos.

The commonly used standard cell has a width of 1 cm, and thus for very pure water in equilibrium with air would have a resistance of about 106 ohm, known as a megohm. Ultra-pure water could achieve 18 megohms or more. Thus in the past, megohm-cm was used, sometimes abbreviated to "megohm". Sometimes, conductivity is given in "microSiemens" (omitting the distance term in the unit). While this is an error, it can often be assumed to be equal to the traditional μS/cm.

The conversion of conductivity to the total dissolved solids depends on the chemical composition of the sample and can vary between 0.54 and 0.96. Typically, the conversion is done assuming that the solid is sodium chloride, i.e., 1 μS/cm is then equivalent to about 0.64 mg of NaCl per kg of water.

Molar conductivity has the SI unit S m2 mol−1. Older publications use the unit Ω−1 cm2 mol−1.

Measurement

The electrical conductivity of a solution of an electrolyte is measured by determining the resistance of the solution between two flat or cylindrical electrodes separated by a fixed distance.[4] An alternating voltage is used in order to avoid electrolysis. The resistance is measured by a conductivity meter. Typical frequencies used are in the range 1–3 kHz. The dependence on the frequency is usually small,[5] but may become appreciable at very high frequencies, an effect known as the Debye–Falkenhagen effect.

A wide variety of instrumentation is commercially available.[6] There are two types of cell, the classical type with flat or cylindrical electrodes and a second type based on induction.[7] Many commercial systems offer automatic temperature correction. Tables of reference conductivities are available for many common solutions.[8]

Definitions

Resistance, R, is proportional to the distance, l, between the electrodes and is inversely proportional to the cross-sectional area of the sample, A (noted S on the Figure above). Writing ρ (rho) for the specific resistance (or resistivity),

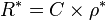

In practice the conductivity cell is calibrated by using solutions of known specific resistance, ρ*, so the quantities l and A need not be known precisely.[9] If the resistance of the calibration solution is R*, a cell-constant, C, is derived.

The specific conductance, κ (kappa) is the reciprocal of the specific resistance.

Conductivity is also temperature-dependent. Sometimes the ratio of l and A is called as the cell constant, denoted as G*, and conductance is denoted as G. Then the specific conductance κ (kappa), can be more conveniently written as

Theory

The specific conductance of a solution containing one electrolyte depends on the concentration of the electrolyte. Therefore, it is convenient to divide the specific conductance by concentration. This quotient, termed molar conductivity, is denoted by Λm

Strong electrolytes

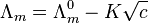

Strong electrolytes are believed to dissociate completely in solution. The conductivity of a solution of a strong electrolyte at low concentration follows Kohlrausch's Law

where  is known as the limiting molar conductivity, K is an empirical constant and c is the electrolyte concentration. (Limiting here means "at the limit of the infinite dilution".) In effect, the observed conductivity of a strong electrolyte becomes directly proportional to concentration, at sufficiently low concentrations i.e. when

is known as the limiting molar conductivity, K is an empirical constant and c is the electrolyte concentration. (Limiting here means "at the limit of the infinite dilution".) In effect, the observed conductivity of a strong electrolyte becomes directly proportional to concentration, at sufficiently low concentrations i.e. when

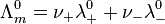

As the concentration is increased however, the conductivity no longer rises in proportion. Moreover, Kohlrausch also found that the limiting conductivity of anions and cations are additive: the conductivity of a solution of a salt is equal to the sum of conductivity contributions from the cation and anion.

where:

-

and

and  are the number of moles of cations and anions, respectively, which are created from the dissociation of 1 mole of the dissolved electrolyte;

are the number of moles of cations and anions, respectively, which are created from the dissociation of 1 mole of the dissolved electrolyte; -

and

and  are the limiting molar conductivities of the individual ions.

are the limiting molar conductivities of the individual ions.

The following table gives values for the limiting molar conductivities for selected ions.

Limiting ion conductivity in water at 298 K Cations λ+0 /mS m2mol−1 anions λ-0 /mS m2mol−1 H+ 34.96 OH− 19.91 Li+ 3.869 Cl− 7.634 Na+ 5.011 Br− 7.84 K+ 7.350 I− 7.68 Mg2+ 10.612 SO42− 15.96 Ca2+ 11.900 NO3− 7.14 Ba2+ 12.728 CH3CO2− 4.09

An interpretation of these results was based on the theory of Debye and Hückel.[10]

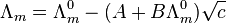

where A and B are constants that depend only on known quantities such as temperature, the charges on the ions and the dielectric constant and viscosity of the solvent. As the name suggests, this is an extension of the Debye–Hückel theory, due to Onsager. It is very successful for solutions at low concentration.

Weak electrolytes

A weak electrolyte is one that is never fully dissociated (i.e. there are a mixture of ions and complete molecules in equilibrium). In this case there is no limit of dilution below which the relationship between conductivity and concentration becomes linear. Instead, the solution becomes ever more fully dissociated at weaker concentrations, and for low concentrations of "well behaved" weak electrolytes, the degree of dissociation of the weak electrolyte becomes proportional to the inverse square root of the concentration.

Typical weak electrolytes are weak acids and weak bases. The concentration of ions in a solution of a weak electrolyte is less than the concentration of the electrolyte itself. For acids and bases the concentrations can be calculated when the value(s) of the acid dissociation constant(s) is(are) known.

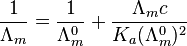

For a monoprotic acid, HA, obeying the inverse square root law, with a dissociation constant Ka, an explicit expression for the conductivity as a function of concentration, c, known as Ostwald's dilution law, can be obtained.

Higher concentrations

Both Kohlrausch's law and the Debye-Hückel-Onsager equation break down as the concentration of the electrolyte increases above a certain value. The reason for this is that as concentration increases the average distance between cation and anion decreases, so that there is more inter-ionic interaction. Whether this constitutes ion-association is a moot point. However, it has often been assumed that cation and anion interact to form an ion-pair. Thus the electrolyte is treated as if it were like a weak acid and a constant, K, can be derived for the equilibrium

- A+ + B−

A+B−; K=[A+] [B−]/[A+B−]

A+B−; K=[A+] [B−]/[A+B−]

Davies describes the results of such calculations in great detail, but states that K should not necessarily be thought of as a true equilibrium constant, rather, the inclusion of an "ion-association" term is useful in extending the range of good agreement between theory and experimental conductivity data.[11] Various attempts have been made to extend Onsager's treament to more concentrated solutions.[12]

The existence of a so-called conductance minimum has proved to be a controversial subject as regards interpretation. Fuoss and Kraus suggested that it is caused by the formation of ion-triplets,[13] and this suggestion has received some support recently.[14][15]

Conductivity Versus Temperature

Generally the conductivity of a solution increases with temperature, as the mobility of the ions increases. For comparison purposes reference values are reported at an agreed temperature, usually 298 K (~25 C), although occasionally 20C is used. So called 'compensated' measurements are made at a convenient temperature but the value reported is a calculated value of the expected value of conductivity of the solution, as if it had been measured at the reference temperature (usually 298 K (~25 C), although occasionally 20C is used). Basic compensation is normally done by assuming a linear increase of conductivity versus temperature of typically 2% per degree.

Solvent isotopic effect

The change in conductivity due to isotopic effect for deuterated electrolytes is sizable.[16]

Applications

Notwithstanding the difficulty of theoretical interpretation, measured conductivity is a good indicator of the presence or absence of conductive ions in solution, and measurements are used extensively in many industries.[17] For example, conductivity measurements are used to monitor quality in public water supplies, in hospitals, in boiler water and industries which depend on water quality such as brewing. This type of measurement is not ion-specific; it can sometimes be used to determine the amount of total dissolved solids (T.D.S.) if the composition of the solution and its conductivity behavior are known.[1] It should be noted that conductivity measurements made to determine water purity will not respond to non conductive contaminants (many organic compounds fall into this category), therefore additional purity tests may be required depending on application.

Sometimes, conductivity measurements are linked with other methods to increase the sensitivity of detection of specific types of ions. For example, in the boiler water technology, the boiler blowdown is continuously monitored for "cation conductivity", which is the conductivity of the water after it has been passed through a cation exchange resin. This is a sensitive method of monitoring anion impurities in the boiler water in the presence of excess cations (those of the alkalizing agent usually used for water treatment). The sensitivity of this method relies on the high mobility of H+ in comparison with the mobility of other cations or anions.

Conductivity detectors are commonly used with ion chromatography.[18]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Conductometry. |

- Debye–Falkenhagen effect

- Wien effect

- Svante Arrhenius

- Alfred Werner - coordination chemistry

- Conductimetric titration - methods to determine the equivalence point

References

- 1 2 Gray, James R. (2004). "Conductivity Analyzers and Their Application". In Down, R.D; Lehr, J.H. Environmental Instrumentation and Analysis Handbook. Wiley. pp. 491–510. ISBN 978-0-471-46354-2. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- ↑ "Water Conductivity". Lenntech. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ↑ "Sailinity measuring units - NSW Environment & Heritage". nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- ↑ Bockris, J. O'M.; Reddy, A.K.N; Gamboa-Aldeco , M. (1998). Modern Electrochemistry (2nd. ed.). Springer. ISBN 0-306-45555-2. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- ↑ Marija Bešter-Rogač and Dušan Habe, "Modern Advances in Electrical Conductivity Measurements of Solutions", Acta Chim. Slov. 2006, 53, 391–395 (pdf)

- ↑ Boyes, W. (2002). Instrumentation Reference Book (3rd. ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-7123-8. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- ↑ Gray, p 495

- ↑ "Conductivity ordering guide" (PDF). EXW Foxboro. 3 October 1999. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ↑ "ASTM D1125 - 95(2005) Standard Test Methods for Electrical Conductivity and Resistivity of Water". Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- ↑ Wright, M.R. (2007). An Introduction to Aqueous Electrolyte Solutions. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-84293-5.

- ↑ Davies, C.W. (1962). Ion Association. London: Butterworths.

- ↑ Miyoshi, K. (1973). "Comparison of the Conductance Equations of Fuoss - Onsager, Fuoss-Hsia and Pitts with the Data of Bis(2, 9-dimethyl-1, 10-phenanthroline)Cu(I) Perchlorate". Bull. Chem. Soc. Japan 46 (2): 426–430. doi:10.1246/bcsj.46.426.

- ↑ Fuoss, R.M.; Kraus, C.A. (1935). "Properties of Electrolytic Solutions. XV. Thermodynamic Properties of Very Weak Electrolytes". J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 57: 1–4. doi:10.1021/ja01304a001.

- ↑ Weingärtner, H.; Weiss, V.C.; Schröer, W. (2000). "Ion association and electrical conductance minimum in Debye–Hückel-based theories of the hard sphere ionic fluid". J. Chem. Phys. 113 (2): 762–. Bibcode:2000JChPh.113..762W. doi:10.1063/1.481822.

- ↑ Schröer, W.; Weingärtner, H. (2004). "Structure and criticality of ionic fluids". Pure Appl. Chem. 76 (1): 19–27. doi:10.1351/pac200476010019. pdf

- ↑ http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/ja970118o

- ↑ "Electrolytic conductivity measurement, Theory and practice" (PDF). Aquarius Technologies Pty Ltd.

- ↑ "Detectors for ion-exchange chromatography". Retrieved 17 May 2009.

- Friedman, Harold L. (1965). "Relaxation Term of the Limiting Law of the Conductance of Electrolyte Mixtures". The Journal of Chemical Physics 42 (2): 462. Bibcode:1965JChPh..42..462F. doi:10.1063/1.1695956.

|