Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross

| Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Awarded by the Führer and Reichspräsident | |

| Type | Neck order |

| Eligibility | Military personnel |

| Awarded for | Awarded to holders of the Iron Cross to recognise extreme battlefield bravery or outstanding military leadership |

| Campaign | World War II |

| Status | Obsolete |

| Statistics | |

| Established | 1 September 1939 |

| First awarded | 30 September 1939 |

| Last awarded | 11 May 1945 / 17 June 1945[Note 1] |

| Posthumous awards |

Swords: 15 Oak Leaves: 95 Knight's Cross: 581 |

| Distinct recipients |

Golden Oak Leaves: 1 Diamonds: 27 Swords: 160 Oak Leaves: 890 Knight's Cross: 7,364 |

| Precedence | |

| Next (higher) | Grand Cross of the Iron Cross |

| Next (lower) | Iron Cross 1st Class |

The Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross (German language: Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes), or simply the Knight's Cross (Ritterkreuz), was a grade of the 1939 version of the Iron Cross (Eisernes Kreuz), which had been created in 1813. The Knight's Cross was the highest award made by Nazi Germany to recognise extreme battlefield bravery or outstanding military leadership during World War II. Among the military decorations of Nazi Germany, it was second only to the Grand Cross of the Iron Cross (Großkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes), an award that was given only once, to Nazi leader and Hitler's second-in-command Hermann Göring. He was granted it as a result of his services in building up the Luftwaffe (the German air force), and for serving as its commander-in-chief. The Knight's Cross was therefore functionally the highest order that German soldiers of all rank could obtain.

The Knight's Cross grade of the Iron Cross was worn at the neck and was slightly larger but similar in appearance to the 1813 Iron Cross. It was legally based on the 1 September 1939 renewal of the Iron Cross. The order could be presented to German soldiers of all ranks and to soldiers from other Axis countries. Its first presentation was made on 30 September 1939, following the German Invasion of Poland, which marked the beginning of World War II in Europe. As the war progressed, some of the recipients distinguished themselves further, and a higher grade, the Oak Leaves to the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross (Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes mit Eichenlaub), was instituted in 1940. In 1941, two higher grades of the Knight's Cross with Oak Leaves were instituted. These were the Knight's Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords (Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes mit Eichenlaub und Schwertern) and the Knight's Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds (Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes mit Eichenlaub, Schwertern und Brillanten). At the end of 1944 the final grade, the Knight's Cross with Golden Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds (Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes mit goldenem Eichenlaub, Schwertern und Brillanten), was created. The Golden Oak Leaves to the Knight's Cross was verifiably awarded only once, to Hans-Ulrich Rudel on 29 December 1944.

The last legal presentation of the Knight's Cross, in any of its grades, had to be made before 23:01 Central European Time 8 May 1945, the time when the German surrender became effective. A number of presentations were made after this date, the last on 17 June 1945. These late presentations are considered de facto but not de jure awards. In post-World War II Germany, the Federal Republic of Germany prohibited the wearing of Nazi insignia. In 1957 the German government authorized a replacement Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross, with an oak leaf cluster in place of the swastika, which could be worn by World War II Knight's Cross recipients. In 1986, the Association of Knight's Cross Recipients (AKCR) acknowledged 7,321 presentations made to the members of the three military branches of the Wehrmacht—the Heer (Army), Kriegsmarine (Navy) and Luftwaffe (Air Force)—as well as the Waffen-SS, the Reichsarbeitsdienst (RAD—Reich Labour Service) and the Volkssturm (German national militia). There were also 43 recipients in the military forces of allies of the Third Reich for a total of 7,364 recipients.[2] Analysis of the German Federal Archives revealed evidence for 7,161 officially—de facto and de jure—bestowed recipients, including one additional presentation previously unidentified by the AKCR.[3] The AKCR names 890 recipients of the Oak Leaves to the Knight's Cross, including the eight recipients who served in the military forces of other Axis countries. The German Federal Archives do not substantiate 27 of these Oak Leaves recipients. The Swords to the Knight's Cross were awarded 160 times according to the AKCR, among them the posthumous presentation to the Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, 13 of which cannot be supported by the German Federal Archives. The Diamonds to the Knight's Cross were awarded 27 times, all of which are verifiable in the German Federal Archives.

Historic background

The Prussian king Friedrich Wilhelm III established the Iron Cross (Eisernes Kreuz) at the beginning of the Befreiungskrieg (War of Liberation) as part of the Napoleonic Wars. Karl Friedrich Schinkel received the contract to design a silver-framed cast iron cross on 13 March 1813. The decree was then backdated to 10 March 1813, the birthday of the King's wife, Louise of Prussia, who had died in 1810.[4] Iron was a material which symbolised defiance and reflected the spirit of the age. The Prussian state had mounted a campaign steeped in patriotic rhetoric to rally their citizens to repulse the French occupation. To finance the military opposition against Napoleon I the king implored wealthy Prussians to turn in their jewels in exchange for a men's cast-iron ring or a ladies' brooch, each bearing the legend "Gold I gave for iron" (Gold gab ich für Eisen) or alternatively, "Gold for defence, Iron for honour" (Gold zur Wehr, Eisen zur Ehr).

Initially, the Iron Cross award was of a temporary nature and could only be made when the country was in a state of war. A formal renewal procedure was required every time the award was to be presented.[5] The renewal date, relating to the year of re-institution, therefore appears on the lower obverse arm of the Iron Cross. The Iron Cross was renewed twice after the Napoleonic Wars and prior to World War II. Its first renewal on 19 July 1870 was related to the Franco-Prussian War and its second renewal came on 5 August 1914, with the outbreak of World War I. The 1914 Iron Cross remained a Prussian decoration but could be awarded in the name of the Kaiser (as the King of Prussia) to members of all the German states' armies and of the Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial Navy). The regulation was extended and from 16 March 1915 the award could also be presented to individuals in the military forces of allies of the German state. During this period the Iron Cross was only awarded in three grades; the Iron Cross 2nd Class (Eisernes Kreuz 2. Klasse), Iron Cross 1st Class (Eisernes Kreuz 1. Klasse) and the Grand Cross of the Iron Cross (Großkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes) leaving a large gap between grades. There was no nationwide decoration placed between the Iron Cross 2nd and 1st Class, which could be awarded to soldiers of all ranks, and the Grand Cross of the Iron Cross, which was awarded only to senior commanders for winning a major battle or campaign. This gap was partly filled by awards given from the Empire's member states. Among the best known of these awards are the Prussian Order Pour le Mérite and House Order of Hohenzollern, which could only be awarded to officers. For non-commissioned officers and soldiers the Prussian Golden Military Merit Cross (Goldenes Militär-Verdienstkreuz) was the highest achievable decoration. With the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II at the end of World War I the awards granted by the various royal households became obsolete.[6]

With the outbreak of World War II on 1 September 1939, Adolf Hitler in his role as commander in chief of the German armed forces (Oberster Befehlshaber der deutschen Wehrmacht) decreed the renewal of the Iron Cross of 1939. The decree was also signed by the Chief of the Armed Forces High Command, Wilhelm Keitel, the Minister of the Interior, Wilhelm Frick and by the State-Minister and Chief of the Presidential Chancellery of the Führer and Reich Chancellor, Otto Meißner.[7] The renewal of 1939 also filled the gap between the Iron Cross 1st Class and the Grand Cross of the Iron Cross. Rather than using an unrelated award to bridge this gap, a new grade of the Iron Cross series was introduced, the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross (Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes).[6] The Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross, without distinction, was awarded to officers and soldiers alike, conforming with the National Socialist political slogan: "One people, one nation, one leader" (Ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Führer).[8]

The Knight's Cross grades of the Iron Cross

Adolf Hitler decreed on the first day of hostilities of World War II the renewal of the Iron Cross.

Since I have decided to call the German people to arms to guard against the threat of attack, I now renew in memory of the heroic battles which Germany's sons have endured protecting the homeland in previous great wars, the order of the Iron Cross.

The legal grounds for this decree had been established in 1937. Paragraph §3 of the German law of Titles, Orders and Honorary Signs (Gesetz über Titel, Orden und Ehrenzeichen) from 1 July 1937 (Reichsgesetzblatt I S. 725[9]) made the Führer and Reichskanzler the only person who was allowed to award orders or honorary signs. The re-institution of the Iron Cross was therefore a Führer decree based on the enactment (Reichsgesetzblatt I S. 1573[10]) of 1 September 1939 Verordnung über die Erneuerung des Eisernen Kreuzes (Ordinance re-establishing the Iron Cross). This had certain political implication since the Treaty of Versailles had explicitly denied Germany the creation of a military decoration, order or medal. The re-institution was more than just a symbolic act. While the renewals of the Iron Cross of 1870 and 1914 had renewed a Prussian honorary sign, the renewal of 1 September 1939 in contrast for the first time had created an honorary sign of the entire German state.[7]

The Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross and its higher grades was awarded for a wide range of reasons and across all ranks, including to a senior commander for skilled leadership of his troops in battle, or to a low-ranking soldier for a single act of extreme gallantry.[6] As the war progressed four additional grades were introduced to further distinguish those who had already won the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross or one of the higher grades and who continued to show merit in combat bravery or military success and the Knight's Cross was eventually awarded in five grades:

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Golden Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds.

Knight's Cross (Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes)

| Manufacturer | PKZ #[Note 2] | LDO #[Note 3] |

|---|---|---|

| C. E. Juncker | 2 | L/12 |

| Otto Schickle | — | L/15 |

| Steinhauer & Lück | 4 | L/16 |

| Klein & Quenzer | (65) | L/26 |

| Gebrüder Godet & Co. | 21 | L/50 |

| C. F. Zimmermann | 20 | L/52 |

The Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross is based on the enactment (Reichsgesetzblatt I S. 1573[10]) of 1 September 1939 Verordnung über die Erneuerung des Eisernen Kreuzes (Ordinance re-establishing the Iron Cross). Its appearance was very similar to the Iron Cross. Its shape was that of a cross pattée, a cross that has arms which are narrow at the center and broader at the perimeter.[11]

The most common Knight's Crosses were produced by the manufacturer Steinhauer & Lück in Lüdenscheid. The Steinhauer & Lück crosses are stamped with the digits "800", indicating 800 grade silver, on the reverse side. These digits can also be found on the band clip. The Steinhauer & Lück Knight's Cross are 48.19 millimetres (1.897 in) wide and 54.12 millimetres (2.131 in) high. Its weight, without band clip, is 28.79 grams (1.016 oz).[12]

-

Ribbon bar

-

Ribbon bar (version)

-

.jpg)

Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross

-

Brevet (certificate of award)

| Verordnung über die Erneuerung des Eisernen Kreuzes | Enactment regarding the renewing of the Iron Cross |

| Nachdem ich mich entschlossen habe, das Deutsche Volk zur Abwehr gegen die ihm drohenden Angriffe zu den Waffen zu rufen, erneuere ich eingedenk der heldenmütigen Kämpfe, die Deutschlands Söhne in den früheren großen Kriegen zum Schutze der Heimat bestanden haben, den Orden des Eisernen Kreuzes. | After I decided to call the German people to arms in defense of the threat of being attacked, I renew in memory of the heroic battles, which Germany's sons have endured protecting the homeland in previous great wars, the Order of the Iron Cross. |

| Artikel 1 | Article 1 |

Das Eiserne Kreuz wird in folgender Abstufung und Reihenfolge verliehen:

|

The Iron Cross will be awarded in the following grades and order:

|

| Artikel 2 | Article 2 |

| Das Eiserne Kreuz wird ausschließlich für besondere Tapferkeit vor dem Feind und für hervorragende Verdienste in der Truppenführung verliehen. Die Verleihung einer höheren Klasse setzt den Besitz der vorangehenden Klasse voraus. | The Iron Cross is exclusively awarded for bravery before the enemy and for excellent merits in commanding troops. The award of a higher class must be preceded by the award of all preceding classes. |

| Artikel 3 | Article 3 |

| Die Verleihung des Großkreuzes behalte ich mir vor für überragende Taten, die den Verlauf des Krieges entscheidend beeinflussen. | I reserve for myself the power to award the Grand Cross of the Iron Cross, for superior actions that decisively influence the course of the war. |

| Artikel 4 | Article 4 |

| Das Eiserne Kreuz 2. Klasse und das Eiserne Kreuz 1. Klasse gleichen in Größe und Ausführung den bisherigen mit der Abweichung, daß auf der Vorderseite das Hakenkreuz und die Jahreszahl 1939 angebracht sind.

Die 2. Klasse wird an einem schwarz-weiß-roten Bande im Knopfloch oder an der Schnalle, die 1. Klasse ohne Band auf der linken Brustseite getragen. Das Ritterkreuz ist größer als das Eiserne Kreuz 2. Klasse. Es wird an einem schwarz-weiß-roten Bande am Halse getragen. Das Großkreuz ist etwa doppelt so groß wie das Eiserne Kreuz 2. Klasse. Es wird an einem breiteren schwarz-weiß-roten Bande am Halse getragen. |

The 2nd Class and 1st Class are of the same size and format as previous versions with the exception that the front sides bears the swastika and the date 1939.

The 2nd Class is worn on a black-white-red band in the buttonhole or clasp, the 1st Class without band on the left breast side. The Knight's Cross is larger in size than the Iron Cross 1st Class and is worn around the neck (neck order) with a black-white-red band. The Grand Cross is approximately twice the size of the Iron Cross 1st Class, a golden trim instead of the silver trim and is worn around the neck with a broader black-white-red band. |

| Artikel 5 | Article 5 |

| Ist der Beliehene schon im Besitz einer oder beider Klassen des Eisernen Kreuzes des Weltkrieges, so erhält er an Stelle eines zweiten Kreuzes eine silberne Spange mit dem Hoheitszeichen und der Jahreszahl 1939 zu dem Eisernen Kreuz des Weltkrieges verliehen; die Spange wird beim Eisernen Kreuz 2. Klasse auf dem Bande getragen, beim Eisernen Kreuz 1. Klasse über dem Kreuz angesteckt. | In case the recipient already owns one or two of the classes of the Iron Cross from the World War, then instead of a second Cross a silver clasp to Iron Cross of the World War bearing the national emblem and the date 1939 is awarded; in case of the 2nd Class the clasp is worn on the band, in case of the 1st Class above the Cross. |

| Artikel 6 | Article 6 |

| Der Beliehene erhält eine Besitzurkunde. | The recipient receives a certificate of ownership. |

| Artikel 7 | Article 7 |

| Das Eiserne Kreuz verbleibt nach dem Ableben des Beliehenen als Erinnerungsstück den Hinterbliebenen. | The Iron Cross shall be retained as an heirloom by the heirs of the recipient after his demise. |

| Artikel 8 | Article 8 |

| Die Durchführungsbestimmungen erläßt der Chef des Oberkommandos der Wehrmacht im Einverständnis mit dem Staatsminister und Chef der Präsidialkanzlei.

Berlin, den 1. September 1939. |

The processing provisions are released by the Supreme Command of the Armed Forces in cooperation with the State Minister and Chief of the Presidential Chancellery.

Berlin, 1 September 1939 |

| Der Führer Adolf Hitler |

Der Führer Adolf Hitler |

| Der Chef des Oberkommandos der Wehrmacht Wilhelm Keitel |

Chief of the Armed Forces High Command Wilhelm Keitel |

| Der Reichsminister des Innern Dr. Wilhelm Frick |

Minister of the Interior Dr. Wilhelm Frick |

| Der Staatsminister und Chef der Präsidialkanzlei des Führers und Reichskanzlers Otto Meißner |

State-Minister and Chief of the Presidential Chancellery of the Führer and Reich Chancellor Otto Meißner |

Knight's Cross with Oak Leaves (mit Eichenlaub)

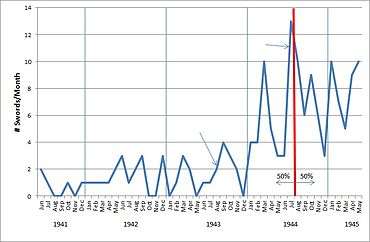

The Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves (Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes mit Eichenlaub) was based on enactment (Reichsgesetzblatt I S. 849[13]) of 3 June 1940 which augmented article 1 and 4 of the 1939 Ordinance re-establishing the Iron Cross. Before the introduction of the Oak Leaves only 124 members of the Wehrmacht had received the Knight's Cross. Prior to Case Yellow (Fall Gelb), the attack on the Netherlands, Belgium and France, just 52 Knight's Crosses had been awarded. In May 1940 the number of presentations peaked. The timing for the introduction of the Oak Leaves is closely linked to Case Red (Fall Rot), the second and decisive phase of the Battle of France.[14]

Like the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross to which it was added, the Oak Leaves clasp could be awarded for leadership, distinguished service or personal gallantry.[15] The Oak Leaves, just like the 1813 Iron Cross and Grand Cross of the Iron Cross, was not a National Socialist invention. The Oak Leaves originally appeared in conjunction with the Golden Oak Leaves of the Red Eagle Order (Roter Adlerorden), which was the second highest Prussian order after the Black Eagle Order (Schwarzer Adlerorden). The 1705 established Red Eagle Order had received the Oak Leaves with a cabinet of the king decree on 18 January 1811. Friedrich Wilhelm III had also ordered the Oak Leaves to be part of the Iron Cross design in commemoration of his 1810 deceased wife, Queen Louise of Prussia. The king also awarded the Oak Leaves together with the Pour le Mérite since 9 October 1813 to honour the soldierly merit before the enemy.[16]

The decoration consisted of a cluster of three oak-leaves with the centre leaf superimposed on the two lower leaves. The middle of the Oak Leaves were decorated by a stylized letter "L" in memoriam of Louise of Prussia. The original clasp was die-struck from 900 grade silver and 2 centimetres (0.79 in) in diameter. The clasp had a pebbled matt finish, with the edges and central ribs of the leaves burnished.[17] The official manufacturer of the Oak Leaves was exclusively the firm Gebrüder Godet & Co. (Godet Brothers & Co.) in Berlin.[Note 4] Godet & Co manufactured two variants of the Oak Leaves which mainly distinguished itself in the appearance of the Oak Leaves on the front right side. Additionally the second variant had a more massive appearance. The first variant was produced until mid 1943.[18]

-

Ribbon bar

-

Ribbon bar (version)

-

With Oak Leaves

-

Detail

| Gebrüder Godet & Co. Type |

Dimensions | Material | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height | Width | Weight | ||

| Type 1—"L/50" | 19.1 mm (0.75 in) | 20.1 mm (0.79 in) | 6.7 g (0.24 oz) | Silver 900 |

| Type 2—"21" | 19.2 mm (0.76 in) | 20.0 mm (0.79 in) | 6.9 g (0.24 oz) | Silver 900 |

| Artikel 1 | Article 1 |

|

|

| Artikel 4 | Article 4 |

| Das Eichenlaub zum Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes besteht aus drei silbernen Eichenblättern, die auf der Bandspange aufliegen. | The Oak Leaves to the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross are made of three silver oak leaves attached to the band clasp. |

Knight's Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords (mit Eichenlaub und Schwertern)

The Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords (Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes mit Eichenlaub und Schwertern) was based on enactment (Reichsgesetzblatt I S. 613[19]) of 28 September 1941 which again augmented articles 1 and 4. The Oak Leaves with Swords clasp was similar in appearance to the Oak Leaves clasp with the exception that a pair of crossed swords were soldered to the base of the Oak Leaves. The reverse side mounted band clip was slightly larger than the one attached to the Oak Leaves without swords. For added stability the swords were soldered to both the Oak Leaves and the clip. The swords are 24 millimetres (0.94 in) long. The entire Oak Leaves with Swords clasp was 24.83 millimetres (0.978 in) wide, 27.58 millimetres (1.086 in) high and had a weight of 9.03 grams (0.319 oz).[20]

-

Ribbon bar

-

Ribbon bar (version)

-

With Oak Leaves and Swords

| Artikel 1 | Article 1 |

|

|

| Artikel 4 | Article 4 |

| Das Eichenlaub mit Schwertern zeigt unter den drei silbernen Blättern zwei gekreuzte Schwerter. Bei dem Eichenlaub mit Schwertern und Brillanten sind die drei silbernen Blätter und die Schwertgriffe mit Brillanten besetzt. |

The Oak Leaves and Swords depict two crossed swords beneath the three silver leaves. In case of the Oak Leaves with Swords and Diamonds the three silver leaves and the hilts of the swords are jewelled with Diamonds. |

Knight's Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds (mit Eichenlaub, Schwertern und Brillanten)

The Knight's Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds (Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes mit Eichenlaub, Schwertern und Brillianten) is like the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords based on enactment (Reichsgesetzblatt I S. 613[19]) of 28 September 1941. The first version was based on the design of the Oak Leaves with Swords clasp manufactured by the firm Gebrüder Godet & Co. in Berlin and had the same size. The clasp was drilled out to accept the Diamonds. This first version was awarded to the first two recipients, Werner Mölders and Adolf Galland, before production was transferred to the firm of Otto Klein in Hanau.[21] The first soldier to receive the Otto Klein variant of the Diamonds was Gordon Gollob on 30 August 1942. Presentation of the Otto Klein Diamonds came as a set and included the more elaborate A-piece and the quiet gift of a second clasp with rhinestones for everyday wear, the B-piece.[22] The Diamonds were awarded 27 times during World War II. However three individuals never received a set of Diamonds. Hans-Joachim Marseille, the fourth recipient, was killed in an aircraft crash prior to its presentation. The deteriorating situation and the end of the war prevented its presentation to Karl Mauss, the 26th recipient and Dietrich von Saucken, the 27th and final recipient.[23]

-

Ribbon bar

-

Ribbon bar (version)

-

With Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds

-

Helmut Lent's Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds on display at the Bundeswehr Military History Museum in Dresden.

| Manufacturer | Dimensions | Construction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height | Width | Weight | Material | Stone | ||

| Gebrüder Godet & Co. | 30.1 mm (1.19 in) | 19.9 mm (0.78 in) | 9.3 g (0.33 oz) | Silver | Diamonds | |

| Otto Klein | A-piece | 32.2 mm (1.27 in) | 22.4 mm (0.88 in) | 14.4 g (0.51 oz) | Platinum | Diamonds |

| B-piece | 33.3 mm (1.31 in) | 22.5 mm (0.89 in) | 9.0 g (0.32 oz) | Silver | Rhinestone | |

Knight's Cross with Golden Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds (mit Goldenem Eichenlaub, Schwertern und Brillanten)

The Knight's Cross with Golden Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds (Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes mit Goldenem Eichenlaub, Schwertern und Brillianten) is based on enactment (Reichsgesetzblatt 1945 I S. 11[24]) of 29 December 1944 which augmented articles 1, 2 and 4. The firm Otto Klein from Hanau manufactured six sets of Golden Oak Leaves and delivered them to the Präsidialkanzlei (Presidential Chancellery). Each set consisted of an A-piece, made of "740" gold (18 Carat) with 58 real diamonds and a B-piece, made of "585" gold (14 Carat) with 68 real sapphires. One of these sets was presented to Hans-Ulrich Rudel on 1 January 1945, the remaining five sets were taken to Schloss Klessheim, where they were captured by the US 3rd Infantry Division.[25] The A-piece has a weight of 13.2 grams (0.47 oz), thus it is slightly lighter than the platinum made A-piece of the silver Diamonds.[26]

-

Ribbon bar

-

Ribbon bar (version)

-

With Golden Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds

-

Rear side of the Oak Leaves of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross

| Artikel 1 | Article 1 |

|

|

| Artikel 2 | Article 2 |

| Das Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes mit dem Goldenen Eichenlaub mit Schwertern und Brillanten wird nur zwölf mal verliehen, um höchstbewährte Einzelkämpfer, die mit allen Stufen des Ritterkreuzes des Eisernen Kreuzes ausgezeichnet sind, vor dem Deutschen Volke besonders zu ehren. | The Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Golden Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds is to be awarded twelve times only, to honor before the German people the most successful combatants, that have received all grades of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross. |

| Artikel 4 | Article 4 |

| Bei dem Goldenen Eichenlaub mit Schwertern und Brillanten sind die drei Blätter und die Schwerter in Gold ausgeführt und wie bei dem silbernen Eichenlaub mit Brillanten besetzt. | In case of the Golden Oak Leaves with Swords and Diamonds the three leaves and the swords are made of gold and likewise jewelled with Diamonds. |

Award documentation

At first, the recipient of the Knight's Cross, or one of its higher grades, received a brief telegram informing him of the award of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross. Thereafter he received a Vorläufiges Besitzzeugnis (Preliminary Testimonial of Ownership). The wording was standardized reading "The Führer and commander in chief of the Armed Forces has awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross <recipients name>" and pre-printed format.[27] The award was also noted in the recipients Soldbuch (Soldiers Pay Book), his Wehrpass (Military Identification) and personnel records.[28]

The preliminary testimonial of ownership was followed by a more elaborate and formal award document, the Ritterkreuzurkunde (Knight's Cross Certificate). The official award document that came with the Knight's Cross was hand-lettered on vellum and placed inside a large red leather binder embossed with a gold Reichsadler. Sometimes, Hitler's signature was a facsimile, but when time allowed, he did sign them. These documents for the Knight's Cross were used between 1939 and 1942, when the number of recipients made it possible only for documents of this type to be made for the higher grades of the order.

The document folder itself was designed by Frieda Thiersch.

Nomination and approval procedure

| Award |

|

Nomination | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Every presentation of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross, or one of its higher grades, was preceded by one or multiple deeds, but also by a nomination (Verleihungsvorschlag). Nominations for the Knight's Cross could be made at company level or higher. Commanders could not nominate themselves.[29] In this instance the division adjutant made the recommendation. In the Luftwaffe the lowest level was the Geschwader and in the Kriegsmarine the respective flotilla was authorized to make the nomination. It was also possible to nominate subordinated foreign units. The nomination by the troop had to be submitted in writing and in double copy. The format and the content were predefined. Every nomination contained the personal data, the rank and unit at the time of the bravery-act, since when the soldier held this position, the employment status (for example "of the Reserves"), the occupation (if Reserves), the peacetime unit (if professional soldier), the military service entry date, previous military decorations awarded and date of presentation, and the profession of the father. For enlisted soldiers and noncommissioned officers the résumé had to be submitted as well.[30]

The nomination had to be forwarded in writing by a courier up the official command chain. Every intermittent administrative office or commander between the nominating unit and the commander-in-chief of the respective Wehrmacht branch (commander-in-chief of the Heer, commander-in-chief of the Luftwaffe and commander-in-chief of the Kriegsmarine with their respective staff offices) had to give their approval along with a short comment. In exceptional cases, such as the nominated individual had sustained severe injuries or that the command chain had been interrupted, a nomination could be submitted via teleprinter communication.[30]

Approval authority

1 September 1939 to 20 April 1945

Administration/Berlin (preliminary decision) → Chief of the Heerespersonalamt/Berlin (preliminary decision) → Oberkommando der Wehrmacht-Department/Berlin (presenting) → Hitler (decision)[31]

The Army Personnel Branch Office was split due to the deteriorating war situation and was moved to Marktschellenberg in the time frame 21 to 24 April 1945.[31]

25 April 1945 to 30 April 1945 (Hitlers death)

Administration/Marktschellenberg (preliminary decision) → deputy Chief of the Heerespersonalamt/Marktschellenberg (preliminary decision) → Chief of the HPA/Berlin (preliminary decision) → OKW-Department/Berlin (presenting) → Hitler (decision)[32]

30 April 1945 onwards

The approval authority of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross became confusing after Hitler's death on 30 April 1945. General Ernst Maisel, deputy chief of Army Personnel Office, was authorized by the Presidential Chancellery to approve presentations of the Knights Cross effective as of 28 April 1945. Maisel, on 30 April, legally approved and conferred 33 Knight's Crosses, 29 nominations were rejected and four were deferred.[33] Hitler's death ended Maisel's authority to approve nominations. The authority to approve and make presentations was passed on to Hitler's successor as Staatsoberhaupt (Head of State) Karl Dönitz, who held the title of Reichspräsident (President) and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces.[34]

3 May 1945

A teleprinter message dated 3 May 1945 was sent to the Commander-in-Chiefs of those units still engaged in combat, empowering them to make autonomous presentations of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross themselves. The following decision making chains of command were possible at this time:[34]

- Northern sector

- Administration (preliminary decision) → Chief of the Heerespersonalamt/Flensburg (preliminary decision) → Chief of the OKW/Flensburg (presenting) → Dönitz/Flensburg (decision)

- Commander-in-Chief North: Ernst Busch

- Commander-in-Chief Army Group Courland: Carl Hilpert

- Commander-in-Chief East Prussia: Dietrich von Saucken

- Commander-in-Chief Norway: Franz Böhme

- Commander-in-Chief Denmark: Georg Lindemann

- Commander-in-Chief Army Group Vistula: Kurt von Tippelskirch (the army group was annihilated on 3 May 1945 and removed from the distribution list)

- Southern sector

- Commander-in-Chief Army Group G: Albert Kesselring

- Commander-in-Chief Army Group E: Alexander Löhr

- Commander-in-Chief Army Group Ostmark: Lothar Rendulic

- Commander-in-Chief Army Group Centre: Ferdinand Schörner

- Commander-in-Chief Army Group C: Heinrich von Vietinghoff (the army group was annihilated on 2 May 1945 and removed from the distribution list)

Prerequisites

To qualify for the Knight's Cross, a soldier had to already hold the 1939 Iron Cross First Class, though the Iron Cross First Class was awarded concurrently with the Knight's Cross in some rare cases. Unit commanders could also be awarded the medal for the exemplary conduct of the unit as a whole. Also, U-boat commanders could qualify for sinking 100,000 tons of shipping and Luftwaffe pilots could qualify for accumulating 20 "points" (with one point being awarded for shooting down a single-engine plane, two points for a twin-engine plane and three for a four-engine plane, with all points being doubled at night). It was issued from 1939 to 1945, with the requirements being gradually raised as the war went on.

Recipients

Distribution by service

The Association of Knight's Cross Recipients (AKCR) names 7,321 recipients of the Knight's Cross in the three military branches of the Wehrmacht, consisting of the Heer (Army), Kriegsmarine (Navy) and Luftwaffe (Air force), the Waffen-SS, the Reichsarbeitsdienst (RAD) and the Volkssturm.[35] The AKCR also lists 43 individuals from non-German Axis forces for a total of 7,364 recipients of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross.[36] Of these 890 individuals received Oak Leaves (882 members of the Wehrmacht and 8 non-Germans); 160 received Oak Leaves and Swords (159 members of the Wehrmacht and one honorary recipient, the Japanese admiral Isoroku Yamamoto). Only 27 men were awarded the Diamonds grade of the Knight's Cross (3 field marshals, 10 generals, 3 colonels, 9 ace pilots and 2 U-boat captains); Hans-Ulrich Rudel was the only recipient of the Knight's Cross with Golden Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds.

Among those generally accepted 159 German recipients of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords are 13 recipients, whose Swords to the Knight's Cross do not meet the formal awarding criteria of the Knight's Cross. Twenty-four recipients of the Knight's Cross with Oak Leaves are also lacking sustainable evidence that their listing is justifiable. Otto Weidinger, Günther-Eberhardt Wisliceny, Sylvester Stadler and Wilhelm Bittrich received the Swords from SS Obergruppenführer Josef Dietrich, who was not legally authorized to present the award.

Further, Hermann Fegelein was executed in the last days of the war for desertion, a charge which upon conviction would have legally deprived him of all rank and awards, including his Knight's Cross. However, his might have been an extralegal execution. According to the recollections of Wilhelm Mohnke, he and the three other general officers tasked with holding a court martial for Fegelein found him to be of such unsound mind that he was not competent to stand trial under military law. Fegelein subsequently disappeared in the hands of Gruppenführer Johann Rattenhuber, who had been one of the empaneled court-martial judges and the Führerbunker's Reichssicherheitsdienst security squad. Fegelein was executed by firing squad.[37]

Author Veit Scherzer concluded that every presentation of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross, or one of its higher grades, made until 20 April 1945 is verifiable in the German Federal Archives. The first echelon of the Heerespersonalamt Abteilung P 5/Registratur (Army Personnel Office Department P 5/Registry) was relocated from Zossen in Brandenburg to Traunstein in Bavaria on this day and the confusion regarding who can be considered a legitimate Knight's Cross recipient began.[38]

Among the officers who participated in the plot to assassinate Hitler on 20 July 1944 were thirteen recipients of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross. In addition, 711 recipients of the Knight's Cross later served in the Bundeswehr, with 114 of them reaching the rank of general.[39]

Award ceremony

Hitler quite frequently made the presentations of the Oak Leaves and higher grades to the bestowed himself in order to express his gratitude personally. The first presentations in 1940 and 1941 were made in the Reich Chancellery in Berlin or on the Berghof in Obersalzberg near Berchtesgaden. Beginning with Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union, in the summer of 1941 the presentations were made at the Führerhauptquartier "Wolf's Lair" (Wolfschanze) near Rastenburg in East Prussia, from the summer 1942 until October 1942 in the Führerhauptquartier "Wehrwolf" near Vinnytsia in Ukraine and then again in the "Wolfschanze". From early 1944 until mid July 1944 the ceremony was again held on the Obersalzberg. This was continued until about August 1944, shortly after the July 20 plot, the failed assassination attempt of Oberst Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg. Later onwards the presentation were only made sporadically by Hitler himself. The last presentations by Hitler were made early in 1945 in the Führerbunker in Berlin. After the July 20 plot senior commanders like the commander in chief of the Kriegsmarine (Oberbefehlshaber der Kriegsmarine) or the commander in chief of the Luftwaffe (Oberbefehlshaber der Luftwaffe) and from the fall of 1944 also by the Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, made the presentations.[40]

| Beginning letter | Recipients According to AKCR |

Additional recipients According to Veit Scherzer |

Delisted According to AKCR |

Disputed According to Veit Scherzer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 118[41] | — |

1[42] | 3[43] |

| Ba–Bm, Bn–Bz | 368[44] + 357[45] = 725 | — | 1[46] | 13[47] + 8[48] = 21 |

| C | 82[49] | — | — | — |

| D | 238[50] | — | — | 6[51] |

| E | 188[52] | — | — | 3[53] |

| F | 280[54] | — | 1[1] | 12[55] |

| G | 380[56] | — | 1[57] | 11[58] |

| Ha–Hm, Hn–Hz | 437[59] + 224[60] = 661 | — | 1[61] | 15[62] + 14[63] = 29 |

| I | 26[64] | — | — | — |

| J | 142[65] | — | 1[1] | 4 |

| Ka–Km, Kn–Kz | 289[66] + 428[67] = 717 | — | 1[68] | 4[69] + 8[70] = 12 |

| L | 386[71] | — | — | 16[72] |

| M | 457[73] | — | 1 | 7 |

| N | 145[74] | — | 2[75] | 2[76] |

| O | 82[77] | — | — | 2[78] |

| P | 324[79] | — | 1 | 5[80] |

| Q | 7[81] | — | — | — |

| R | 447[82] | 1[83] | — | 11 |

| Sa–Schr, Schu–Sz | 457[84] + 603[85] = 1,060 | — | — | 11[86] + 14[87] = 25 |

| T | 182[88] | — | — | 5 |

| U | 32[89] | — | — | 1[90] |

| V | 92[91] | — | — | 5 |

| W | 446[92] | — | — | 11 |

| X | 1 | — | — | — |

| Z | 103[93] | — | — | 2[94] |

| Totals | 7,321 | 1 | 11 | 193 |

Association of Knight's Cross Recipients

The Association of Knight's Cross Recipients (AKCR) (German language: Ordensgemeinschaft der Ritterkreuzträger des Eisernen Kreuzes e.V. (OdR)) is an association of highly decorated front-line soldiers of both world wars. The association was founded in 1955 in Köln-Wahn. Generaloberst Alfred Keller, Knight of the Order Pour le Mérite and Recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross, called upon the recipients of the highest combat decorations for bravery to organize an association for tradition. Later, the Recipients of the Prussian Golden Military Merit Cross, or the Pour le Mérite for enlisted personnel, were included. The memorandum of the AKCR incorporates the awarding of 7318 Knight's Crosses, as well as 882 Oakleaves, 159 Swords, 27 Diamonds, 1 Golden Oak Leaves and 1 Grand Cross of the Iron Cross for all ranks in the three branches of the Wehrmacht and the Waffen-SS.[95]

In 1999, German Minister of Defense Rudolf Scharping banned all kinds of official contacts between the Bundeswehr and the Association of Knight's Cross Recipients, stating that the Association and many of its members shared neo-Nazi and revanchistic ideas which were not in conformity with the German constitution and Germany's postwar policies.[96]

Dönitz-decree

Großadmiral and President of Germany Karl Dönitz, Hitler's successor as Head of State (Staatsoberhaupt) and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces, had declared that "All nominations for the bestowal of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross and their higher grades which have been received by the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht — staff of the Wehrmacht high command — until the capitulation becomes effective are approved, under the premise that all nominations are formally and correctly approved by the nominating authorities of the Wehrmacht, Heer including the Waffen-SS, Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe all the way to the level of the army and army group leadership."[97] This "Dönitz-decree" (German: Dönitz-Erlaß) is most likely dated from 7 May 1945. Manfred Dörr, author of various publications related to the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross, requested legal counsel on this decree in 1988. The Deutsche Dienststelle (WASt) came to the conclusion that this decree is unlawful and bears no legal justification. This blanket decree is not in line with the law governing the bestowal of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross which requires a case by case decision.[98]

Law about Titles, Orders and Honorary Signs

The German Law about Titles, Orders and Honorary Signs (German language: Gesetz über Titel, Orden und Ehrenzeichen) (BGBl. I S. 334)[99] regulates the wearing of the Knight's Cross in post World War II Germany. The reason for this is that German law prohibits wearing a swastika, so on 26 July 1957 the West German government authorized replacement Knight's Crosses with an Oak Leaf Cluster in place of the swastika, similar to the Iron Crosses of 1813, 1870 and 1914, which could be worn by World War II Knight's Cross recipients.

Military slang

In the military slang of the German soldiers the Knight's Cross is often referred to as the Blechkrawatte (tin-necktie). Glory-hungry soldiers seeking this medal (which was worn conspicuously around the neck or throat) were seen as suffering from Halsschmerzen: a cynical slang-term play on the word meaning "afflicted with throat trouble", having a "neck rash", "itching neck" or "sore throat". (Navy slang: Draufgänger: a U-boat commander who was viewed as a "daredevil" seeking to earn the Knight's Cross by being too aggressive in endangering his own submarine and crew in pursuit of enemy ships. Different degrees of the Iron Cross were awarded based upon the number and/or tonnage of enemy ships sunk.)

The term Ritterkreuz-Auftrag ("Knight's Cross Mission") referred to a mission that was extremely dangerous, or a no-win situation.

Footnotes

- ↑ Großadmiral Karl Dönitz had ordered the cessation of all promotions and awards as of 11 May 1945 (Dönitz decree). Consequently the last Knight's Cross awarded to Oberleutnant zur See of the Reserves Georg-Wolfgang Feller on 17 June 1945 must therefore be considered a de facto but not de jure award.[1]

- ↑ PKZ stands for Präsidialkanzlei—Presidential Chancellery

- ↑ LDO is the abbreviation of Leistungsgemeinschaft der Deutschen Ordenshersteller—Performance or service community of German order manufacturers

- ↑ The company Gebrüder Godet & Co (brothers Godet & Co.) was founded 1761 by the goldsmith Jean Godet. The company Godet was one of the first German manufactures of orders and honorary signs in Germany. Godet became the prime royal warrant for orders under the leadership of Jean Fredric Godet. The company was known as J. Godet & Söhne between 1864 and 1924. The company name then changed to Eugen Godet & Co. The name changed again in the late 1920s or early 1930s to Gebrüder Godet & Co.

References

- Citations

- 1 2 3 Fellgiebel 2000, p. 4.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 113–460, 483, 485–487, 492, 494, 498–499, 501, 503, 509.

- ↑ Scherzer 2007, pp. 117–186.

- ↑ Potempa 2003, p. 9.

- ↑ Schaulen 2003, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 Williamson 2004, p. 3.

- 1 2 Schaulen 2003, p. 6.

- ↑ Maerz 2007, p. 29.

- ↑ "Reichsgesetzblatt Teil I S. 725; 1 July 1937" (PDF). ALEX Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (in German). Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- 1 2 "Reichsgesetzblatt Teil I S. 1573; 1 September 1939" (PDF). ALEX Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (in German). Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ↑ Williamson 2004, p. 4.

- ↑ Schaulen 2004, p. 10.

- ↑ "Reichsgesetzblatt Teil I S. 849; 3 June 1940" (PDF). ALEX Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (in German). Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ↑ Maerz 2007, p. 238

- ↑ Williamson 2005, p. 7.

- ↑ Schaulen 2003, p. 9.

- ↑ Williamson 2005, p. 3.

- ↑ Schaulen 2004, p. 11.

- 1 2 "Reichsgesetzblatt Teil I S. 613; 28 September 1941" (PDF). ALEX Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (in German). Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ↑ Schaulen 2004, p. 12.

- ↑ Williamson 2006, p. 3.

- ↑ Maerz 2007, p. 300.

- ↑ Maerz 2007, p. 293.

- ↑ "Reichsgesetzblatt 1945 I S. 11; 29 December 1944" (PDF). ALEX Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (in German). Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ↑ Maerz 2007, pp. 310–311.

- ↑ Maerz 2007, p. 314.

- ↑ Williamson 2004, p. 5.

- ↑ Williamson 2004, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Scherzer 2007, p. 30.

- 1 2 Scherzer 2007, p. 31.

- 1 2 Scherzer 2007, p. 50.

- ↑ Scherzer 2007, p. 52.

- ↑ Scherzer 2007, p. 62.

- 1 2 Scherzer 2007, p. 63.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 113–460, 485–488, 499, 501, 503, 509

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 461–463, 510

- ↑ O'Donnell, James P. (2001) [1978]. The Bunker. New York: Da Capo Press. pp. 182–183. ISBN 0-306-80958-3.

- ↑ Scherzer 2007, p. 15.

- ↑ German Ministry of Defence (BMVg) on the Iron Cross.

- ↑ Schaulen 2003, p. 11.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 113–118.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, p. 483.

- ↑ Scherzer 2007, p. 117.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 119–135, 485–486.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 135–152, 487.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, p. 150.

- ↑ Scherzer 2007, pp. 117–122.

- ↑ Scherzer 2007, pp. 122–125.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 152–156, 488.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 156–167.

- ↑ Scherzer 2007, pp. 126–127.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 167–176.

- ↑ Scherzer 2007, pp. 127–128.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 176–189.

- ↑ Scherzer 2007, pp. 128–131.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 154, 190–208, 488.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Scherzer 2007, pp. 131–135.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 208–228.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 229–239.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, p. 492.

- ↑ Scherzer 2007, pp. 136–141.

- ↑ Scherzer 2007, pp. 141–145.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 239–240.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 241–247.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 248–261.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 261–281.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, p. 494.

- ↑ Scherzer 2007, pp. 147–149.

- ↑ Scherzer 2007, pp. 149–151.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 282–299.

- ↑ Scherzer 2007, pp. 151–157.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 300–320, 498.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 321–327.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 499, 511.

- ↑ Scherzer 2007, p. 161.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 327–331.

- ↑ Scherzer 2007, pp. 161–162.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 332–346, 499.

- ↑ Scherzer 2007, p. 162–163

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, p. 347.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 347–368, 501.

- ↑ Scherzer 2007, p. 630.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 369–390.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 390–418, 503.

- ↑ Scherzer 2007, p. 168–172

- ↑ Scherzer 2007, p. 173–178

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 418–427.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 427–429.

- ↑ Scherzer 2007, p. 180.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 429–433.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 433–455, 509.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, pp. 455–460.

- ↑ Scherzer 2007, p. 186.

- ↑ Association of Knight's Cross Recipients

- ↑ Official Note of the German Parliament about contacts between the Bundeswehr and Nazi traditionalist associations

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, last page of the addendum

- ↑ Scherzer 2007, pp. 69-74.

- ↑ BGBl. I S. 334 @ Bundesministerium der Justiz

- Bibliography

- Berger, Florian (1999). Mit Eichenlaub und Schwertern. Die höchstdekorierten Soldaten des Zweiten Weltkrieges [With Oak Leaves and Swords. The Highest Decorated Soldiers of the Second World War] (in German). Vienna, Austria: Selbstverlag Florian Berger. ISBN 978-3-9501307-0-6.

- Fellgiebel, Walther-Peer (2000) [1986]. Die Träger des Ritterkreuzes des Eisernen Kreuzes 1939–1945 — Die Inhaber der höchsten Auszeichnung des Zweiten Weltkrieges aller Wehrmachtteile [The Bearers of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross 1939–1945 — The Owners of the Highest Award of the Second World War of all Wehrmacht Branches] (in German). Friedberg, Germany: Podzun-Pallas. ISBN 978-3-7909-0284-6.

- Fraschka, Günther (1994). Knights of the Reich. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Military/Aviation History. ISBN 978-0-88740-580-8.

- MacLean, French L. (2007). Luftwaffe Efficiency & Promotion Reports For The Knight's Cross Winners

- Maerz, Dietrich (2007). Das Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes und seine Höheren Stufen (in German). Richmond, MI: B&D Publishing LLC. ISBN 978-0-9797969-1-3.

- Maerz, Dietrich (2007) "The Knights Cross of the Iron Cross and its Higher Grades" (in English), Richmind, MI, B&D Publishing LLC, ISBN 978-0-9797969-0-6.

- Potempa, Harald (2003). Das Eiserne Kreuz—Zur Geschichte einer Auszeichnung (in German). Luftwaffenmuseum der Bundeswehr Berlin-Gatow.

- Schaulen, Fritjof (2003). Eichenlaubträger 1940 – 1945 Zeitgeschichte in Farbe I Abraham – Huppertz [Oak Leaves Bearers 1940 – 1945 Contemporary History in Color I Abraham – Huppertz] (in German). Selent, Germany: Pour le Mérite. ISBN 978-3-932381-20-1.

- Schaulen, Fritjof (2004). Eichenlaubträger 1940 – 1945 Zeitgeschichte in Farbe II Ihlefeld - Primozic [Oak Leaves Bearers 1940 – 1945 Contemporary History in Color II Ihlefeld - Primozic] (in German). Selent, Germany: Pour le Mérite. ISBN 978-3-932381-21-8.

- Schaulen, Fritjof (2005). Eichenlaubträger 1940 – 1945 Zeitgeschichte in Farbe III Radusch – Zwernemann [Oak Leaves Bearers 1940 – 1945 Contemporary History in Color III Radusch – Zwernemann] (in German). Selent, Germany: Pour le Mérite. ISBN 978-3-932381-22-5.

- Scherzer, Veit (2007). Die Ritterkreuzträger 1939–1945 Die Inhaber des Ritterkreuzes des Eisernen Kreuzes 1939 von Heer, Luftwaffe, Kriegsmarine, Waffen-SS, Volkssturm sowie mit Deutschland verbündeter Streitkräfte nach den Unterlagen des Bundesarchives [The Knight's Cross Bearers 1939–1945 The Holders of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross 1939 by Army, Air Force, Navy, Waffen-SS, Volkssturm and Allied Forces with Germany According to the Documents of the Federal Archives] (in German). Jena, Germany: Scherzers Miltaer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-938845-17-2.

- Williamson, Gordon & Bujeiro, Ramiro (2004). Knight's Cross and Oak Leaves Recipients 1939-40. Osprey Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-84176-641-0.

- Williamson, Gordon & Bujeiro, Ramiro (2005). Knight's Cross and Oak Leaves Recipients 1941-45. Osprey Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-84176-642-9.

- Williamson, Gordon (2006). Knight's Cross, Oak-Leaves and Swords Recipients 1941-45. Osprey Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-84176-643-7.

- Williamson, Gordon (2006). Knight's Cross with Diamonds Recipients 1941-45. Osprey Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-84176-644-5.

External links

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross @ Feldgrau.com

- Memorial to the Order.

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross @ Angelfire.com

- Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes @ Lexikon der Wehrmacht (German)

- Knights Cross Award Document

| ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||