Dál Riata

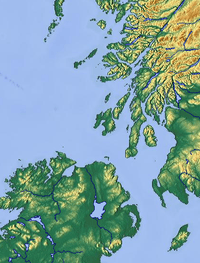

Dál Riata (also Dalriada or Dalriata), a Gaelic overkingdom, included parts of western Scotland and northeastern Ulster in Ireland (across the North Channel). In the late 6th–early 7th centuries it encompassed roughly what present-day Argyll and Lochaber in Scotland and County Antrim in Ulster.[1]

In Argyll it consisted initially of three kindreds:

- Cenél Loairn (kindred of Loarn) in north and mid-Argyll

- Cenél nÓengusa (kindred of Óengus) based on Islay

- Cenél nGabráin (kindred of Gabrán) based in Kintyre

A fourth kindred, Cenél Chonchride in Islay, was seemingly too small to be deemed a major division. By the end of the 7th century another kindred, Cenél Comgaill (kindred of Comgall), had emerged, based in eastern Argyll. The Lorn and Cowal districts of Argyll take their names from Cenél Loairn and Cenél Comgaill respectively,[1] while the Morvern district was formerly known as Kinelvadon, from the Cenél Báetáin, a subdivision of the Cenél Loairn.[2]

Latin-language sources often referred to the inhabitants of Dál Riata as Scots (Scoti in Latin), a name originally used by Roman and Greek writers for the Irish who raided Roman Britain. Later it came to refer to Gaelic-speakers, whether from Ireland or elsewhere.[3] They are referred to herein as Gaels, an unambiguous term, or as Dál Riatans.[4]

The kingdom reached its height under Áedán mac Gabráin (r. 574–608), but King Æthelfrith of Bernicia checked its growth at the Battle of Degsastan in 603. Serious defeats in Ireland and Scotland in the time of Domnall Brecc (d. 642) ended Dál Riata's "golden age", and the kingdom became a client of Northumbria, then subject to the Picts. There is disagreement over the fate of the kingdom from the late eighth-century onwards. Some scholars have seen no revival of Dál Riata after the long period of foreign domination (after 637 to around 750 or 760), while others have seen a revival of Dál Riata under Áed Find (736–778), and later under Kenneth MacAlpin (Cináed mac Ailpín, who (some sources claim) took the kingship there in c.840 following the disastrous defeat of the Pictish army by the Danes): some even claim that the Dál Riata usurped the kingship of Fortriu several generations before MacAlpin (800–858).[5] The kingdom's independence ended in the Viking Age, as it merged with the lands of the Picts to form the Kingdom of Alba.

The name of the kingdom survives in the terminology of the Dalradian geological series, a term coined by Archibald Geikie in 1891 because its outcrop has a similar geographical reach to that of the former Dál Riata.

Name

The name Dál Riata is derived from Old Irish. Dál, cognate to English dole and deal, German Teil / Theil, and Latin tāliō and descendants including French taille and Italian taglia, means "portion" or "share" (as in "a portion of land"); Riata or Riada is believed to be a personal name.[6] Thus, the name refers to "Riada's portion" of territory in the area.

People, land and sea

The modern human landscape of Dál Riata differs a great deal from that of the first millennium. Most people today live in settlements far larger than anything known in early times, while some areas, such as Kilmartin and many of the islands, such as Islay and Tiree may well have had as many inhabitants as they do today. Many of the small settlements have now disappeared, so that the countryside is far emptier than was formerly the case, and many areas which were formerly farmed are now abandoned. Even the physical landscape is not entirely as it was: sea-levels have changed, and the combination of erosion and silting will have considerably altered the shape of the coast in some places, while the natural accumulation of peat and man-made changes from peat-cutting has altered inland landscapes.[7]

As was normal at the time, subsistence farming was the occupation of most people. Oats and barley were the main cereal crops. Pastoralism was especially important, and transhumance (the seasonal movement of people with their livestock between fixed summer and winter pastures) was the practice in many places. Some areas, most notably Islay, were especially fertile, and good grazing would have been available all year round, just as it was in Ireland. Tiree was famed in later times for its oats and barley, while smaller, uninhabited islands were used to keep sheep. The area, until lately, was notable for its inshore fisheries, and for plentiful shellfish, therefore seafood is likely to have been an important part of the diet.[8]

The Senchus fer n-Alban lists three main kin groups in Dál Riata in Scotland, with a fourth being added later:[9]

- The Cenél nGabráin, in Kintyre, supposedly the descendants of Gabrán mac Domangairt.

- The Cenél nÓengusa, in Islay and Jura, supposedly the descendants of Óengus Mór mac Eirc.

- The Cenél Loairn, in Lorne, perhaps also Mull and Ardnamurchan, supposedly the descendants of Loarn mac Eirc.[10]

- The Cenél Comgaill, in Cowal and Bute, a later addition, supposedly the descendants of Comgall mac Domangairt.[11]

The Senchus does not list any kindreds in Ireland, but does also list an apparently very minor kindred called Cenel Chonchride in Islay descended from another son of Erc, Fergus Becc. Another kindred, Cenél Báetáin of Morvern (later Clan Maclean), branched off from Cenel Laiorn about the same time Cenel Comgaill separated from its parent kindred. The Cenel Loairn may have been the largest of the "three kindreds", as the Senchus reports it being divided further into Cenel Shalaig, Cenel Cathbath, Cenel nEchdach, Cenel Murerdaig. Among the Cenél Loairn it also lists the Airgíalla, although whether this should be understood as being Irish settlers or simply another tribe to whom the label was applied is unclear. Bannerman proposes a tie to the Uí Macc Uais.[12] The meaning of Airgíalla 'hostage givers' adds to the uncertainty, although it must be observed that only one grouping in Ireland was apparently given this name and it is therefore very rare, perhaps supporting the Ui Macc Uais hypothesis. There is no reason to suppose that this is a complete or accurate list.[13]

Among the royal centres in Dál Riata, Dunadd appears to have been the most important. It has been partly excavated, and weapons, quern-stones and many moulds for the manufacture of jewellery were found in addition to fortifications. Other high-status material included glassware and wine amphorae from Gaul, and in larger quantities than found elsewhere in Britain and Ireland. Lesser centres included Dun Ollaigh, seat of the Cenél Loairn kings, and Dunaverty, at the southern end of Kintyre, in the lands of the Cenél nGabráin.[14] The main royal centre in Ireland appears to have been at Dunseverick (Dún Sebuirge).[15]

The difficulty of overland travel and the many islands made Dál Riata an archipelago, with travel by sea by far the easiest means of moving any distance. As well as long distance trade, local trade must also have been significant.[16] Currachs were probably the most common seagoing craft, and on inland waters dugouts and coracles were used. Large timber ships, called long ships, perhaps similar to the Viking ships of the same name, are attested to in a variety of sources.[17]

Religion and art

No written accounts exist for pre-Christian Dál Riata, and the earliest known records come from the chroniclers of Iona and Irish monasteries. Adomnán's Life of St Columba implies a Christian Dál Riata.[18] Whether this is true cannot be known. The figure of Columba looms large in any history of Christianity in Dál Riata. Adomnán's Life, although useful as a record, was not intended to serve as history, but rather as hagiography. Because the writing of the lives of the saints in Adomnán's day had not reached the stylised formulas of the High Middle Ages, the Life contains a great deal of historically valuable information. It is also a vital linguistic source indicating the distribution of Gaelic and P-Celtic placenames in northern Scotland by the end of the 7th century. It famously notes Columba's need for a translator when conversing with an individual on Skye.[19] This evidence of a non-Gaelic language is supported by a sprinkling of P-Celtic placenames on the remote mainland opposite the island.[20]

Columba's founding Iona within the bounds of Dál Riata ensured that the kingdom would be of great importance in the spread of Christianity in northern Britain, not only to Pictland, but also to Northumbria, via Lindisfarne, to Mercia, and beyond. Although the monastery of Iona belonged to the Cenél Conaill of the Northern Uí Néill, and not to Dál Riata, it had close ties to the Cenél nGabráin, ties which may make the annals less than entirely impartial.[21]

If Iona was the greatest religious centre in Dál Riata, it was far from unique. Lismore, in the territory of the Cenél Loairn, was sufficiently important for the death of its abbots to be recorded with some frequency. Applecross, probably in Pictish territory for most of the period, and Kingarth on Bute are also known to have been monastic sites, and many smaller sites, such as on Eigg and Tiree, are known from the annals.[22] In Ireland, Armoy was the main ecclesiastical centre in early times, associated with Saint Patrick and with Saint Olcán, said to have been first bishop at Armoy. An important early centre, Armoy later declined, overshadowed by the monasteries at Movilla (Newtownards) and Bangor.[23]

As well as their primary spiritual importance, the political significance of religious centres cannot be dismissed. The prestige of being associated with the saintly founder was of no small importance. Monasteries represented a source of wealth as well as prestige. Additionally, the learning and literacy found in monasteries served as useful tools for ambitious kings.[24]

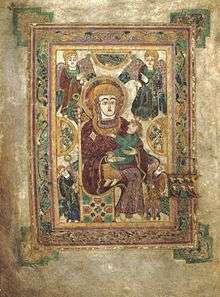

The illuminated manuscript Book of Kells was probably at least begun at Iona, although not by Columba as legend has it, as it dates from about 800 (it may have been commissioned to mark the bicentennial of Columba's death in 597). Whether it was or not, Iona was certainly important in the formation of Insular art, which combined Mediterranean, Anglo-Saxon, Celtic and Pictish elements into a style of which the book of Kells is a late example.

For other arts, a number of sculptures remain to give an impression of Dál Riatan work. The St. Martin's Cross on Iona is the best-preserved high cross, probably inspired by Northumbrian free-standing crosses, such as the Ruthwell Cross, although a similar cross exists in Ireland (Ahenny, County Tipperary). The Kildalton Cross on Islay is similar. A sculpted slab at Ardchattan appears to show strong Pictish influences, while the Dupplin Cross, it has been argued, shows that influences also moved in the opposite direction. Fine Hiberno-Saxon metalwork such as penannular brooches is believed to have been created at Dunadd.[25]

In addition to the monastic sites, a considerable number of churches are attested, not only from archaeological evidence, but also from the evidence of place-names. The element "kil", from Gaelic cill, can be shown in many cases to be associated with early churches, such as at Kilmartin by Dunadd.[26]

History

Origins

The Duan Albanach (Song of the Scots) tells that the three sons of Erc—Fergus Mór, Loarn and Óengus—conquered Alba (Scotland) around 500 AD. Bede offers a different, and probably older, account wherein Dál Riata was conquered by Irish Gaels led by a certain Reuda. Old Gaelic Dál means "portion" or "share", and is usually followed by the name of an eponymous founder.[6] Bede's tale may come from the same root as the Irish tales of Cairpre Riata and his brothers, the Síl Conairi (sons/descendants of Conaire Mór / Conaire Cóem).[28] The story of Dál Riata moves from foundation myth to something nearer to history with the reports of the death of Comgall mac Domangairt around 540 and of his brother Gabrán around 560.[29]

The version of history in the Duan Albanach was long accepted, although it is preceded by the purely fictional tale of Albanus and Brutus conquering Britain. The presence of Gaelic in Scotland was seen as the result of either a large-scale migration from Ireland,[30] or a takeover by Irish Gaelic elites. However, this theory is no longer universally accepted. In his academic paper Were the Scots Irish?, archaeologist Dr Ewan Campbell says that there is no archaeological or placename evidence of a migration or takeover.[31] This lack of archaeological evidence was previously noted by Professor Leslie Alcock.[31] Archaeological evidence shows that Argyll was different from Ireland, before and after the supposed migration, but that it also formed part of the Irish Sea province with Ireland, being easily distinguished from the rest of Scotland.[32] Campbell suggests that Argyll and Antrim formed a "maritime province", united by the sea and isolated from the rest of Scotland by the mountainous ridge called the Druim Alban.[31] This allowed a shared language to be maintained through the centuries; Argyll remained Gaelic-speaking while the rest of Scotland became Pictish/Brittonic-speaking.[31] Campbell argues that the medieval accounts were a kind of dynastic propaganda, constructed to bolster a dynasty's claim to the throne and to bolster Dál Riata claims to territory in Antrim.[31] This view of the medieval accounts is shared by other historians.[31] In her critical analysis of Campbell's paper, Bridget Brennan criticizes his archeological arguments, but says that many of them "are sound, particularly with respect to historical documentation and even to a certain extent the linguistic argument".[33]

However Dál Riata came to be, the time in which it arose was one of great instability in Ulster, following the Ulaid's loss of territory (including the ancient centre of Emain Macha) to the Airgíalla and the Uí Néill. Whether the two parts of Dál Riata had long been united, or whether a conquest in the 4th century or early 5th century, either of Antrim from Argyll, or vice versa, in line with myth, is not known. "The thriving of Dalriada", pp. 47–50, notes that a conquest of Irish Dál Riata from Scotland, in the period after the fall of Emain Macha, fits the facts as well as any other hypothesis.

Linguistic and genealogical evidence associates ancestors of the Dál Riata with the prehistoric Iverni and Darini, suggesting kinship with the Ulaid and a number of shadowy kingdoms in distant Munster. The Robogdii have also been suggested as ancestral.[34] Ultimately the Dál Riata, according to the earliest genealogies, are descendants of Deda mac Sin, a prehistoric king or deity of the Érainn.

Druim Cett to Mag Rath

The history of Dál Riata, while unknown before the middle of the 6th century, and very unclear after the middle of the 8th century, is relatively well recorded in the intervening two centuries, although many questions remain unanswered. As has been said, the origins of the link between Dál Riata in Scotland and Ireland are obscure. What is not in doubt is that Irish Dál Riata was a lesser kingdom of Ulaid. The Kingship of Ulster was dominated by the Dál Fiatach and contested by the Cruithne kings of the Dál nAraidi.[35]

In 575, Columba fostered an agreement between Áedán mac Gabráin and Áed mac Ainmuirech of the Cenél Conaill at Druim Cett. This alliance was likely precipitated by the conquests of the Dál Fiatach king Báetán mac Cairill, one of the very few High Kings of Ireland not of the Connachta or the Uí Néill, who had sought to subjugate all of Dál Riata, and the Isle of Man as well. Báetán died in 581, but the Ulaid kings did not abandon their attempts to control Dál Riata.

The kingdom of Dál Riata reached its greatest extent in the reign of Áedán mac Gabráin. It is said that Áedán was consecrated as king by Columba.[36] If true, this was one of the first such consecrations known. As noted, Columba brokered the alliance between Dál Riata and the Northern Uí Néill. This pact was successful, first in defeating Báetan mac Cairill, then in allowing Áedán to campaign widely against his neighbours, as far afield as Orkney and lands of the Maeatae, on the River Forth. Áedán appears to have been very successful in extending his power, until he faced the Bernician king Æthelfrith at Degsastan c. 603. Æthelfrith's brother was among the dead, but Áedán was defeated, and the Bernician kings continued their advances in southern Scotland. Áedán died c. 608 aged about 70. Dál Riata did expand to include Skye, possibly conquered by Áedán's son Gartnait.

It appears, although the original tales are lost, that Fiachnae mac Báetáin (d. 626), Dál nAraidi King of Ulster, was overlord of both parts of Dál Riata. Fiachnae campaigned against the Northumbrians, and besieged Bamburgh, and the Dál Riatans will have fought in this campaign.[37]

Dál Riata remained allied with the Northern Uí Néill until the reign of Domnall Brecc, who reversed this policy and allied with Congal Cáech (also known as Congal Cláen) of the Dál nAraidi. Domnall joined Congal in a campaign against Domnall mac Áedo of the Cenél Conaill, the son of Áed mac Ainmuirech.[38] The outcome of this change of allies was defeats for Domnall Brecc and his allies on land at Mag Rath (Moira, County Down) and at sea at Sailtír, off Kintyre, in 637. This, it was said, was divine retribution for Domnall Brecc turning his back on the alliance with the kinsmen of Columba.[39] Domnall Brecc's policy appears to have died with him in 642, at his final, and fatal, defeat by Eugein map Beli of Alt Clut at Strathcarron, for as late as the 730s, armies and fleets from Dál Riata fought alongside the Uí Néill.[40]

Mag Rath to the Pictish Conquest

The history of Dál Riata in Ireland after Mag Rath is not entirely clear. It appears that the Uí Chóelbad kings of Dál nAraidi came to control the Glens of Antrim in the years after the battle. The Dál Riatan lands along the River Bush appear to have fallen into the hands of the Cenél nEógain, and the Airgíalla may have benefitted by taking over lands to the south of the Antrim Mountains.[41] It has been proposed that some of the more obscure kings of Dál Riata mentioned in the Annals of Ulster, such as Fiannamail ua Dúnchado and Donncoirce may have been kings of Irish Dál Riata.[42]

The fate of Scottish Dál Riata is no more certain. It does appear that the kingdom was tributary to Northumbrian kings until the Pictish king Bruide mac Bili defeated Ecgfrith of Northumbria at Dun Nechtain in 685. It is not certain that this subjection ended in 685, although this is usually assumed to be the case.[43] However, it appears that Eadberht Eating made some effort to stop the Picts under Óengus mac Fergusa crushing Dál Riata in 740. Whether this means that the tributary relationship had not ended in 685, or if Eadberht sought only to prevent the growth of Pictish power, is unclear.[44]

Since it has been thought that Dál Riata swallowed Pictland to create the Kingdom of Alba, the later history of Dál Riata has tended to be seen as a prelude to future triumphs.[45] The annals make it clear that the Cenél Gabraín lost any earlier monopoly of royal power in the late 7th century and in the 8th, when Cenél Loairn kings such as Ferchar Fota, his son Selbach, and grandsons Dúngal and Muiredach are found contesting for the kingship of Dál Riata. The long period of instability in Dál Riata was only ended by the conquest of the kingdom by Óengus mac Fergusa, king of the Picts, in the 730s. After a third campaign by Óengus in 741, Dál Riata then disappears from the Irish records for a generation.

The last century

Áed Find may appear in 768, fighting against the Pictish king of Fortriu.[46] At his death in 778 Áed Find is called "king of Dál Riata", as is his brother Fergus mac Echdach in 781.[47] The Annals of Ulster say that a certain Donncoirche, "king of Dál Riata" died in 792, and there the record ends. Any number of theories have been advanced to fill the missing generations, none of which are founded on any very solid evidence.[48] A number of kings are named in the Duan Albanach, and in royal genealogies, but these are rather less reliable than we might wish. The obvious conclusion is that whoever ruled the petty kingdoms of Dál Riata after its defeat and conquest in the 730s, only Áed Find and his brother Fergus drew the least attention of the chroniclers in Iona and Ireland. This argues very strongly for Alex Woolf's conclusion that Óengus mac Fergusa "effectively destroyed the kingdom."[49]

It is unlikely that Dál Riata was ruled directly by Pictish kings, but it is argued that Domnall, son of Caustantín mac Fergusa, was king of Dál Riata from 811 to 835. He was apparently followed by the last named king of Dál Riata Áed mac Boanta, who was killed in the great Pictish defeat of 839 at the hands of the Vikings.[50]

From Dál Riata to the Innse Gall

If the Vikings had a great impact on Pictland and in Ireland, in Dál Riata, as in Northumbria, they appear to have entirely replaced the existing kingdom with a new entity. In the case of Dál Riata this was to be known as the kingdom of the Sudreys, traditionally founded by Ketil Flatnose (Caitill Find in Gaelic) in the middle of the 9th century. The Frankish Annales Bertiniani may record the conquest of the Inner Hebrides, the seaward part of Dál Riata, by Vikings in 847.[51]

Alex Woolf has suggested that there occurred a formal division of Dál Riata between the Norse-Gaelic Uí Ímair and the natives, like those divisions that took place elsewhere in Ireland and Britain, with the Norse controlling most of the islands, and the Gaels controlling the Scottish coast and the more southerly islands. In turn Woolf suggests that this gave rise to the terms Airer Gaedel and Innse Gall, respectively "the coast of the Gaels" and the "Islands of the foreigners".[52]

Under the House of Alpin

Woolf has further demonstrated that by the time of Malcolm II, the leading cenela of Dál Riata had moved from the southwest of the region (north of the Firths) to the north, east, and northeast, with Cenel Loairn moving up the Great Glen to occupy Moray, the former and sometimes still Fortriu, one branch of Cenel nGabhrain occupying the district known as Gowrie and another the district of Fife, Cenel nOengusa giving its name to Circinn as Angus, Cenel Comgaill occupying Strathearn, and another lesser known kindred, Cenel Conaing, probably moving to Mar.[53]

In fiction

In Rosemary Sutcliff's 1965 novel The Mark of the Horse Lord the Dál Riada undergo an internal struggle for control of royal succession, and an external conflict to defend their frontiers against the Caledones.

In Rosemary Sutcliff's historical adventure novel The Eagle of the Ninth (1954), a young Roman officer searches to recover the lost Roman eagle standard of his father's legion in the northern part of Great Britain. The story is based on the Ninth Spanish Legion's supposed disappearance in the Scottish Highlands near the end of the Roman occupation. The novel was adapted by Jeremy Brock into the film The Eagle (2011).

In the Kushiel novels (a series, beginning with Kushiel's Dart, 2001), by Jacqueline Carey, the Dalriada of the Kingdom of Alba figure prominently in a Royal marriage and subsequent alliance with France (known in the series as "Terre d'Ange").

In Julian May's Saga of Pliocene Exile series, the non-born Aiken Drum's homeworld is an ethnic Scottish planet called Dalriada.

In the Lost Girl TV series, the pub where the Light Fae and the Dark Fae mingle is called the Dal Riata; named after the ancient kingdom.

In Jules Watson's Dalriada Trilogy (2006–2008), three centuries are chronicled during the time of the Roman Invasion of Britain.

A feature length fantasy film named Dalriata's King is being made in Scotland, with a story based loosely on the first king of the Scots. It is currently in postproduction and the release date is set for late 2016.[54]

Dál Riata is a playable nation in Paradox Interactive's 4X video game Crusader Kings II. At the earliest start date, 769 AD with the Charlemagne DLC, they are an independent petty kingdom and considered ethnically Irish with Catholicism as their default religion. In start dates from 867 to 1241 the area is under first Norse, then Norwegian control, while by the latest 1337 start date it has become a vassal of King David II of Scotland.

Dalriada is the name of a Hungarian folk metal band: Dalriada.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Oxford Companion to Scottish History p. 161 162, edited by Michael Lynch, Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-923482-0.

- ↑ Watson, Celtic Place-names of Scotland, p. 122.

- ↑ Charles-Edwards, Early Christian Ireland, p. 159–160, considers whether the Latin terms Scotti and Atacotti refer to the confederations in Ulster and Leinster respectively. The etymology of Scotti, and its Gaelic roots, if any, are uncertain. The term in late Classical sources is either specifically linked to raiders from Ireland, or is geographically ambiguous. In sharp contrast, no clear reference pointing to Scotti in Scotland in the Roman period has been found. Despite several references listing different combinations of Picti, Scotti, Hiberni, Attecotti and Saxons together as later Roman Britain's archetypal enemies, it is worth noting that 'Scotti' and 'Hiberni' are never listed together, confirming they were then, as they were later, alternative names for the Irish or confederations of the Irish. Regardless of the original sense, or its modern popularity, to use the term "Scot" in this context invites confusion.

- ↑ See 1066 And All That, p. 5, for a parody of the confusion the word "Scot" engenders in this context.

- ↑ Smyth, and Bannerman, Scottish Takeover, present this case, arguing that Pictish kings from Ciniod son of Uuredech and Caustantín onwards were descendants of Fergus mac Echdach and Feradach, son of Selbach mac Ferchair. Broun's Pictish Kings offers an alternative reconstruction, and one which has attracted considerable support, e.g. Clancy, "Iona in the kingdom of the Picts: a note", Woolf, Pictland to Alba, pp 57–67.

- 1 2 Bede, HE, Book I, Chapter 1.

- ↑ See McDonald, Kingdom of the Isles, pp.10–20, for a short discussion of the geography of Dál Riata in Scotland.

- ↑ Campbell, Saints and Sea-kings, pp. 22–29; Foster, Picts, Gaels and Scots, pp. 49–59.

- ↑ The Senchus is translated in Bannerman, Studies, pp. 47–49; previously published in Celtica, vols. 7 (1966) – 9 (1971); earlier translations in Anderson, ESSH, vol. 1, pp. cl–cliii and Skene, Chronicles of the Picts and Scots.

- ↑ Broun, ""Dál Riata", notes that the Senchus treats the Cenél Loairn differently. In fact, it lists the three (actually four) thirds of the Cenél Loairn as the Cenél Shalaig (or Cenél Fergusa Shalaig), Cenél Cathbath, Cenél nEchdach and Cenél Muiredaig. Even the compiler of the Senchus doubts whether their eponymous founders Fergus Shalaig, Cathbad, Eochaid and Muiredach were all sons of Loarn mac Eirc.

- ↑ Bannerman, Studies, p. 110, dates the separation of the Cenél Comgaill from the Cenél nGabráin to around 700.

- ↑ Bannerman, Studies, pp. 115–118. See also Bannerman, Studies, pp. 120 & 122, noting that the Tripartite Life of Saint Patrick appears to refer to a "Cenél nÓengusa" in Antrim.

- ↑ The Annals of Ulster, s.a. 670, refer to the return of the genus Gartnaith, i.e. the Cenél Gartnait, from Ireland to Skye. This Gartnait is presumed to be a son of Áedán mac Gabraín: see Broun, "Dál Riata". Bannerman, Studies, pp. 92–94, identifies this Gartnait as a son of Áedán, whom he sees as the same person as Gartnait, king of the Picts. No such son is named by Adomnán, in the annals, or by the Senchus. See also Adomnán, Life, II, 22, and note 258, where a certain Ioan mac Conaill mac Domnaill is said to have belonged to "the royal lineage of Cenél nGabráin". See also the discussion of the Cenél Loairn above.

- ↑ Bannerman, Studies, pp. 111–118; Campbell, Saints and Sea-kings, pp. 17–28; Foster, Picts, Gaels and Scots, pp. 65–68.

- ↑ T. M. Charles-Edwards, Early Christian Ireland (2000), pp. 57–61.

- ↑ See Adomnán, Life, note 72, where a trading fleet of 50 ships is mentioned; see also Bannerman, Studies, pp. 148–154 for an analysis of Adomnán's reports, and those in the annals, dealing with maritime matters.

- ↑ Adomnán, Life, note 297; Foster, Picts, Gaels and Scots, pp. 99–100.

- ↑ Markus, "Iona"; Markus, "Conversion".

- ↑ As well as Sharpe's translation of Adomnán's Life of St Columba, Broun & Clancy (eds.), Spes Scotorum, is essential reading on Columba, Iona and Scotland.

- ↑ W.F.H. Nicolaisen, Scottish Placenames: Their study and significance (1976).

- ↑ See, for example, Broun, "Dál Riata"; for the evidence of place-names as an indicator of Ionan influence, see Taylor, "Iona abbots".

- ↑ Clancy, "Church institutions".

- ↑ Charles-Edwards, Early Christian Ireland, pp. 58–60.

- ↑ Foster, Picts, Gaels and Scots, pp. 42–44, 94–95 & 104–106.

- ↑ Laing & Laing, The Picts and the Scots, pp 136–137, deals with Dál Riatan arts at greater length; see also Ritchie, "Culture: Picto-Celtic".

- ↑ Markus, "Religious life".

- ↑ Revealed: carved footprint marking Scotland's birth is a replica, The Herald, 22 September 2007.

- ↑ Bannerman,Studies, pp. 122–124.

- ↑ Annals of Ulster, death of Comgall s.a. 538, also s.a. 542, s.a. 545, death of Gabrán s.a. 558, s.a. 560.

- ↑ See Mackie, A History of Scotland, pp. 18–19. Neither Smyth nor Laing & Laing accept the migration theory without reservation.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Campbell, Ewan. "Were the Scots Irish?" in Antiquity No. 75 (2001). pp. 285–292.

- ↑ Campbell, Saints and Sea-kings, pp. 8–15; Foster, Picts, Gaels and Scots, pp. 9–10; Broun, "Dál Riata"; Clancy, "Ireland"; Forsyth, "Origins", pp. 13–17.

- ↑ Brennan, Bridget. A critical analysis of Dr Ewan Campbell's paper "Were the Scots Irish?".

- ↑ see O'Rahilly's historical model

- ↑ For Kings of Ulster see Byrne, Irish Kings and High-Kings, pp. 106–129.

- ↑ Adomnán, Life of St Columba, Book III, Chapter 6.

- ↑ For Báetan and Fiachnae see Byrne, Irish Kings and High-Kings, pp. 109–112, and Ó Cróinín, Early Medieval Ireland, pp. 48–52.

- ↑ See Byrne, Irish Kings and High-Kings, pp. 112–114.

- ↑ See Cumméne's "Life of Columba" quoted in Sharpe's edition of Adomnán, Book III, Chapter 5, and notes 360, 362.

- ↑ Byrne, Irish Kings and High-Kings, p. 114; Annals of the Four Masters, s.a. 728.

- ↑ Charles-Edwards, Early Christian Ireland, pp. 60–62; Byrne, Irish Kings and High-Kings, pp. 112ff.

- ↑ See Bannerman, "Scottish Takeover", pp. 76–77. If Charles-Edwards and Byrne are correct as to the loss of lands in Antrim after Mag Rath, it not obvious how Bannerman's thesis can be accommodated.

- ↑ Adomnán, Life of St Columba, notes 360, 362; Broun, "Dál Riata"; Smyth, Warlords and Holy Men, pp. 116–118; Sharpe, "The thriving of Dalriada", pp. 60–61.

- ↑ Continuation of Bede's Ecclesiastical History (trans. Sellar), s.a. 740; Historia Regum Anglorum of Symeon of Durham, s.a. 740; also the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, manuscript D, which reports the burning of York, see also 741.

- ↑ The titles alone of John Bannerman's "The Scottish Takeover of Pictland" and Richard Sharpe's "The thriving of Dalriada" tell their own story.

- ↑ Annals of Ulster, s.a. 768: "A battle in Foirtriu between Aed and Cinaed." It is assumed that Áed Find is the "Aedh" in question, but cf. the Annals of the Four Masters, s.a. 763—corresponding with anno 768 in the Annals of Ulster—where it is reported: "A battle was fought between the Leinstermen themselves, namely, between Cinaech, son of Flann, and Aedh, at Foirtrinn, where Aedh was slain."

- ↑ Dates from the Annals of Ulster. The Annals of the Four Masters report the deaths of Abbots of Lismore, but nothing of Dál Riata except reports of the death of Áed, s.a. 771, and of his brother Fergus, s.a. 778.

- ↑ See the discussion in Broun, "Pictish Kings", where another theory is advanced.

- ↑ Woolf, "Ungus (Onuist), son of Uurguist."

- ↑ Broun, "Pictish Kings", passim; Clancy, "Caustantín son of Fergus (Uurguist)."

- ↑ Woolf, Pictland to Alba, pp. 99–100 & 286–289; Anderson, Early Sources, p. 277.

- ↑ Alex Woolf, "Age of Sea-Kings", pp. 94–95.

- ↑ Woolf, Alex. From Pictland to Alba, pp. 226–230

- ↑ http://www.fellowshipfilm.com/

References

- Adomnán, Life of St Columba, tr. & ed. Richard Sharpe. Penguin, London, 1995. ISBN 0-14-044462-9

- Anderson, Alan Orr, Early Sources of Scottish History A.D. 500–1286, volume 1. Reprinted with corrections. Paul Watkins, Stamford, 1990. ISBN 1-871615-03-8

- Bannerman, John, Studies in the History of Dalriada. Scottish Academic Press, Edinburgh, 1974. ISBN 0-7011-2040-1

- Bannerman, John, "The Scottish Takeover of Pictland" in Dauvit Broun & Thomas Owen Clancy (eds.) Spes Scotorum: Hope of Scots. Saint Columba, Iona and Scotland. T & T Clark, Edinburgh, 1999. ISBN 0-567-08682-8

- Broun, Dauvit, "Aedán mac Gabráin" in Michael Lynch (ed.), The Oxford Companion to Scottish History. Oxford UP, Oxford, 2001. ISBN 0-19-211696-7

- Broun, Dauvit, "Dál Riata" in Lynch (2001).

- Broun, Dauvit, "Pictish Kings 761–839: Integration with Dál Riata or Separate Development" in Sally M. Foster (ed.), The St Andrews Sarcophagus: A Pictish masterpiece and its international connections. Four Courts, Dublin, 1998. ISBN 1-85182-414-6

- Byrne, Francis John, Irish Kings and High-Kings. Batsford, London, 1973. ISBN 0-7134-5882-8

- Campbell, Ewan, Saints and Sea-kings: The First Kingdom of the Scots. Canongate, Edinburgh, 1999. ISBN 0-8624-1874-7

- Charles-Edwards, T.M., Early Christian Ireland. Cambridge UP, Cambridge, 2000. ISBN 0-521-36395-0

- Clancy, Thomas Owen, "Columba, Adomnán and the Cult of Saints in Scotland" in Broun & Clancy (1999).

- Clancy, Thomas Owen, "Church institutions: early medieval" in Lynch (2001).

- Clancy, Thomas Owen, "Iona in the kingdom of the Picts: a note" in The Innes Review, volume 55, number 1, 2004, pp. 73–76. ISSN 0020-157X

- Clancy, Thomas Owen, "Ireland: to 1100" in Lynch (2001).

- Cowan, E.J., "Economy: to 1100" in Lynch (2001).

- Forsyth, Katherine, "Languages of Scotland, pre-1100" in Lynch (2001).

- Forsyth, Katherine, "Origins: Scotland to 1100" in Jenny Wormald (ed.), Scotland: A History, Oxford UP, Oxford, 2005. ISBN 0-19-820615-1

- Foster, Sally M., Picts, Gaels, and Scots: Early Historic Scotland. Batsford, London, 2004. ISBN 0-7134-8874-3

- Laing, Lloyd & Jenny Lloyd, The Picts and the Scots. Sutton, Stroud, 2001. ISBN 0-7509-2873-5

- Mackie, J.D., A History of Scotland. London: Penguin, 1991. ISBN 0-14-013649-5

- McDonald, R. Andrew, The Kingdom of the Isles: Scotland's Western Seaboard, c. 1100–c. 1336. Tuckwell, East Linton, 2002. ISBN 1-898410-85-2

- Markus, Fr. Gilbert, O.P., "Iona: monks, pastors and missionaries" in Broun & Clancy (1999).

- Markus, Fr. Gilbert, O.P., "Religious life: early medieval" in Lynch (2001).

- Markus, Fr. Gilbert, O.P., "Conversion to Christianity" in Lynch (2001).

- Mac Néill, Eoin, Celtic Ireland. Dublin, 1921. Reprinted Academy Press, Dublin, 1981. ISBN 0-906187-42-7

- Nicolaisen, W.H.F., Scottish Place-names. B.T. Batsford, London, 1976. Reprinted, Birlinn, Edinburgh, 2001. ISBN 0-85976-556-3

- Ó Corráin, Donnchadh, "Vikings in Ireland and Scotland in the ninth century" in Peritia 12 (1998), pp. 296–339. Etext (pdf)

- Ó Cróinín, Dáibhí, Early Medieval Ireland: 400–1200. Longman, London, 1995. ISBN 0-582-01565-0

- Oram, Richard, "Rural society: medieval" in Lynch (2001).

- Owen, Olwyn, The Sea Road: A Viking Voyage through Scotland. Canongate, Edinburgh, 1999. ISBN 0-86241-873-9

- Rodger, N.A.M., The Safeguard of the Sea. A Naval History of Great Britain, volume one 660–1649. Harper Collins, London, 1997. ISBN 0-00-638840-X

- Ross, David, Scottish Place-names. Birlinn, Edinburgh, 2001. ISBN 1-84158-173-9

- Sellar, W.D.H., "Gaelic laws and institutions" in Lynch (2001).

- Sharpe, Richard, "The thriving of Dalriada" in Simon Taylor (ed.), Kings, clerics and chronicles in Scotland 500–1297. Fourt Courts, Dublin, 2000. ISBN 1-85182-516-9

- Smyth, Alfred P., Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland AD 80–1000. Edinburgh UP, Edinburgh, 1984. ISBN 0-7486-0100-7

- Taylor, Simon, "Seventh-century Iona abbots in Scottish place-names" in Broun & Clancy (1999).

- Taylor, Simon, "Place names" in Lynch (2001).

- Woolf, Alex, "Age of Sea-Kings: 900–1300", in Donald Omand (ed.), The Argyll Book. Birlinn, Edinburgh, 2004. ISBN 1-84158-253-0

- Woolf, Alex, "Nobility: early medieval" in Lynch (2001).

- Woolf, Alex, From Pictland to Alba, 789–1070, The New Edinburgh History of Scotland, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-7486-1234-5

External links

- CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts at University College Cork

- The Corpus of Electronic Texts includes the Annals of Ulster, Tigernach, the Four Masters and Innisfallen, the Chronicon Scotorum, the Lebor Bretnach, Genealogies, and various Saints' Lives. Most are translated into English, or translations are in progress

- Annals of Clonmacnoise at Cornell

- Bede's Ecclesiastical History and its Continuation (pdf), at CCEL, translated by A.M. Sellar.

- Digital archive of excavations associated with Lane & Campbell, Dunadd: An early Dalriadic capital at Glasgow University Dept. of Archaeology

- Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (PSAS) through 1999 (pdf).

- A history of Kintyre

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||