The King in Yellow

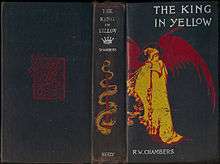

Cover of an 1895 edition[1] | |

| Author | Robert W. Chambers |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Decadent literature, horror, supernatural |

| Publisher | F. Tennyson Neely |

Publication date | 1895 |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 316 |

The King in Yellow is a book of short stories by American writer Robert W. Chambers, first published by F. Tennyson Neely in 1895.[2] The book is named after a fictional play with the same title which recurs as a motif through some of the stories.[3] The first half of the book features highly esteemed weird stories, and the book has been described by critics such as E. F. Bleiler, S. T. Joshi and T. E. D. Klein as a classic in the field of the supernatural.[3][4] There are ten stories, the first four of which ("The Repairer of Reputations", "The Mask", "In the Court of the Dragon", and "The Yellow Sign") mention The King in Yellow, a forbidden play which induces despair or madness in those who read it. "The Yellow Sign" inspired a film of the same name released in 2001.

The British first edition was published by Chatto & Windus in 1895 (316 pages).[5]

Stories

The first four stories are loosely connected by three main devices:

- A fictional play in book form entitled The King in Yellow

- A mysterious and malevolent supernatural entity known as the King in Yellow

- An eerie symbol called the Yellow Sign

These stories are macabre in tone, centering, in keeping with the other tales, on characters that are often artists or decadents.

The first and fourth stories, "The Repairer of Reputations" and "The Yellow Sign", are set in an imagined future 1920s America, whereas the second and third stories, "The Mask" and "In the Court of the Dragon", are set in Paris. These stories are haunted by the theme: "Have you found the Yellow Sign?"

The weird and macabre character gradually fades away during the remaining stories, and the last three are written in the romantic fiction style common to Chambers' later work. They are all linked to the preceding stories by their Parisian setting and their artistic protagonists.

List of stories

The stories in the book are:

- "The Repairer of Reputations" – A powerful, weird story of egotism and paranoia that carries the imagery of the book's title.

- "The Mask" – A dream story of art, love, and uncanny science.

- "In the Court of the Dragon" – A man is pursued by a sinister church organist who is after his soul.

- "The Yellow Sign" – An artist is troubled by a sinister churchyard watchman who resembles a coffin worm.

- "The Demoiselle d'Ys" – A ghost story, the theme of which anticipates H. G. Wells' "The Door in the Wall" (1906).[6]

- "The Prophets' Paradise" – A sequence of eerie prose poems that develop the style and theme of a quote from the fictional play The King in Yellow which introduces "The Mask".

- "The Street of the Four Winds" – An atmospheric tale of an artist in Paris who is drawn to a neighbor's room by a cat; the story ends with a macabre touch.

- "The Street of the First Shell" – A war story set in the Paris Siege of 1870.

- "The Street of Our Lady of the Fields" – Romantic American bohemians in Paris.

- "Rue Barrée" – Romantic American bohemians in Paris, with a discordant ending that playfully reflects some of the tone of the first story.

The play called The King in Yellow

The imaginary play The King in Yellow has two acts and at least three characters: Cassilda, Camilla and "The Stranger", who may or may not be the title character. Chambers' story collection excerpts sections from the play to introduce the book as a whole, or individual stories. For example, "Cassilda's Song" comes from Act 1, Scene 2 of the play:

- Along the shore the cloud waves break,

- The twin suns sink behind the lake,

- The shadows lengthen

- In Carcosa.

- Strange is the night where black stars rise,

- And strange moons circle through the skies,

- But stranger still is

- Lost Carcosa.

- Songs that the Hyades shall sing,

- Where flap the tatters of the King,

- Must die unheard in

- Dim Carcosa.

- Song of my soul, my voice is dead,

- Die thou, unsung, as tears unshed

- Shall dry and die in

- Lost Carcosa.[7]

The short story "The Mask" is introduced by an excerpt from Act 1, Scene 2d:

- Camilla: You, sir, should unmask.

- Stranger: Indeed?

- Cassilda: Indeed it's time. We have all laid aside disguise but you.

- Stranger: I wear no mask.

- Camilla: (Terrified, aside to Cassilda.) No mask? No mask![8]

It is also stated, in the "The Repairer of Reputations", that the final moment of the first act involves the character of Cassilda on the streets, screaming in a horrified fashion, "Not upon us, oh, king! Not upon us!".[9]

All of the excerpts come from Act I. The stories describe Act I as quite ordinary, but reading Act II drives the reader mad with the "irresistible" revealed truths. "The very banality and innocence of the first act only allowed the blow to fall afterward with more awful effect". Even seeing the first page of the second act is enough to draw the reader in: "If I had not caught a glimpse of the opening words in the second act I should never have finished it [...]" ("The Repairer of Reputations").

Chambers usually gives only scattered hints of the contents of the full play, as in this extract from "The Repairer of Reputations":

He mentioned the establishment of the Dynasty in Carcosa, the lakes which connected Hastur, Aldebaran and the mystery of the Hyades. He spoke of Cassilda and Camilla, and sounded the cloudy depths of Demhe, and the Lake of Hali. "The scolloped tatters of the King in Yellow must hide Yhtill forever", he muttered, but I do not believe Vance heard him. Then by degrees he led Vance along the ramifications of the Imperial family, to Uoht and Thale, from Naotalba and Phantom of Truth, to Aldones, and then tossing aside his manuscript and notes, he began the wonderful story of the Last King.

A similar passage occurs in "The Yellow Sign", in which two protagonists have read The King in Yellow:

Night fell and the hours dragged on, but still we murmured to each other of the King and the Pallid Mask, and midnight sounded from the misty spires in the fog-wrapped city. We spoke of Hastur and of Cassilda, while outside the fog rolled against the blank window-panes as the cloud waves roll and break on the shores of Hali.

Influences

Chambers borrowed the names Carcosa, Hali and Hastur from Ambrose Bierce: specifically, his short stories "An Inhabitant of Carcosa" and "Haïta the Shepherd". There is no strong indication that Chambers was influenced beyond liking the names. For example, Hastur is a god of shepherds in "Haïta the Shepherd", but is implicitly a location in "The Repairer of Reputations", listed alongside the Hyades and Aldebaran.[10]

Brian Stableford pointed out that the story "The Demoiselle d'Ys" was influenced by the stories of Théophile Gautier, such as "Arria Marcella" (1852); both Gautier and Chambers' stories feature a love affair enabled by a supernatural time slip.[11] The name Jeanne d'Ys is also a homophone for the word jaundice and continues the symbolism of The King in Yellow.

Cthulhu Mythos

H. P. Lovecraft read The King in Yellow in early 1927[12] and included passing references to various things and places from the book—such as the Lake of Hali and the Yellow Sign — in "The Whisperer in Darkness" (1931),[13] one of his seminal Cthulhu Mythos stories. Lovecraft borrowed Chambers' method of only vaguely referring to supernatural events, entities, and places, thereby allowing his readers to imagine the horror for themselves. The imaginary play The King in Yellow effectively became another piece of occult literature in the Cthulhu Mythos alongside the Necronomicon and others.

In the story, Lovecraft linked the Yellow Sign to Hastur, but from his brief (and only) mention it is not clear what Lovecraft meant Hastur to be. August Derleth developed Hastur into a Great Old One in his controversial reworking of Lovecraft's universe, elaborating on this connection in his own mythos stories. In the writings of Derleth and a few other latter-day Cthulhu Mythos authors, the King in Yellow is an Avatar of Hastur, so named because of his appearance as a thin, floating man covered in tattered yellow robes.

In Lovecraft's cycle of horror sonnets, Fungi from Yuggoth, sonnet XXVII "The Elder Pharos" mentions the last Elder One who lives alone talking to chaos via drums: "The Thing, they whisper, wears a silken mask of yellow, whose queer folds appear to hide a face not of this earth...".[14]

In the Call of Cthulhu roleplaying game published by Chaosium, the King in Yellow is an avatar of Hastur who uses his eponymous play to spread insanity among humans. He is described as a hunched figure clad in tattered, yellow rags, who wears a smooth and featureless "Pallid Mask". Removing the mask is a sanity-shattering experience; the King's face is described as "inhuman eyes in a suppurating sea of stubby maggot-like mouths; liquescent flesh, tumorous and gelid, floating and reforming".

Although none of the characters in Chambers' book describe the plot of the play, Kevin Ross fabricated a plot for the play within the Call of Cthulhu mythos.

References

- ↑ "The King In Yellow: First Edition Controversy". Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- ↑ American Supernatural Tales. Penguin Classics. Penguin Books. 2007. p. 474. ISBN 978-0-14-310504-6.

First publication: Robert W. Chambers, The King in Yellow ... F. Tennyson Neely, 1895

- 1 2 "Robert W. Chambers" in American Supernatural Tales. Penguin Classics. Penguin Books. 2007. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-14-310504-6.

- ↑ Klein, T. E. D. (1986). "Chambers, Robert W(illiam)". In Sullivan, Jack. The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural. New York: Penguin/Viking. pp. 74–6. ISBN 0-670-80902-0.

- ↑ "The King in Yellow". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ↑ "The King in Yellow and Other Horror Stories by Robert W. Chambers - Reviews, Discussion, Bookclubs, Lists". Goodreads. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

- ↑ "The King in Yellow" in e.g. Chambers, Robert W. (2004). The Yellow Sign and Other Stories. Call of Cthulhu Fiction. Chaosium. p. 3. ISBN 1-56882-170-0.

- ↑ "The Mask" in e.g. Chambers, Robert W. (2004). The Yellow Sign and Other Stories. Call of Cthulhu Fiction. Chaosium. p. 33. ISBN 1-56882-170-0.

- ↑ Chambers, Robert W. (2004). The Yellow Sign and Other Stories. Call of Cthulhu Fiction. Chaosium. p. 20. ISBN 1-56882-170-0.

- ↑ Chambers, Robert W. (2000). Joshi, S. T., ed. The Yellow Sign and Other Stories. Oakland, CA: Chaosium. p. xiv. ISBN 978-1-56882-126-9.

- ↑ Brian Stableford, "The King in Yellow" in Frank N. Magill, ed. Survey of Modern Fantasy Literature, Vol 2. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Salem Press, Inc., 1983. (pp. 844-847).

- ↑ Joshi, S. T.; Schultz, David E. (2001). "Chambers, Robert W[illiam]". An H. P. Lovecraft Encyclopedia. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-313-31578-7.

- ↑ Pearsall, Anthony B. "Yellow Sign". The Lovecraft Lexicon (1st ed.). Tempe, AZ: New Falcon. p. 436. ISBN 0-313-31578-7.

- ↑ Lovecraft, Howard Phillips (1971). Fungi from Yuggoth and other poems. Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-02147-2.

Further reading

- Bleiler, Everett (1948). The Checklist of Fantastic Literature. Chicago: Shasta Publishers.

- Rehearsals for Oblivion: Act 1 - Tales of The King in Yellow, edited by Peter A. Worthy, Elder Signs Press, 2007

- Strange Aeons 3'' (an issue dedicated to The King in Yellow, edited by Rick Tillman and K.L. Young, Autumn 2010

- The Hastur Cycle, edited by Robert M. Price, Chaosium, 1993

- The Yellow Sign and Other Stories, edited by S.T. Joshi, Chaosium, 2004

- Watts, Richard; Love, Penelope (1990). Fatal Experiments. Oakland, CA: Chaosium. ISBN 0-933635-72-9.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- The King in Yellow at Project Gutenberg

- The King in Yellow at yankeeclassic.com

- The King in Yellow at sff.net

- The King in Yellow title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- "The King in Yellow": An Introduction by Christophe Thill

- The King in Yellow, part 1 at librivox.org

- The King in Yellow, part 2 at librivox.org

| ||||||||||||||