Ludwig II of Bavaria

| Ludwig II | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

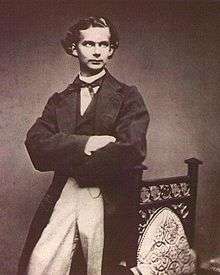

Ludwig in c. 1874 | |||||

| King of Bavaria | |||||

| Reign | 10 March 1864 – 13 June 1886 | ||||

| Predecessor | Maximilian II | ||||

| Successor | Otto | ||||

| Born |

25 August 1845 Nymphenburg Palace, Munich, Bavaria | ||||

| Died |

13 June 1886 (aged 40) Lake Starnberg, Bavaria, German Empire | ||||

| Burial | St. Michael's Church, Munich | ||||

| |||||

| House | Wittelsbach | ||||

| Father | Maximilian II of Bavaria | ||||

| Mother | Marie of Prussia | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholic | ||||

Ludwig II or Ludwig Otto Friedrich Wilhelm (25 August 1845 – 13 June 1886)[1] was King of Bavaria from 1864 until his death. He is sometimes called the Swan King (English) and der Märchenkönig, the Fairy Tale King (German). He also held the titles of Count Palatine of the Rhine, Duke of Bavaria, Duke of Franconia, and Duke in Swabia.[2]

He succeeded to the throne aged 18. Two years later Bavaria and Austria fought a war against Prussia, which they lost. However, in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 they sided with Prussia against France, and after it Bavaria became part of the new German Empire led by Prussia. Ludwig remained King of Bavaria but withdrew from many state affairs remaining within the powers of Bavaria, in favor of extravagant artistic and architectural projects. He commissioned the construction of two lavish palaces and the Neuschwanstein Castle and was a devoted patron of the composer Richard Wagner. Ludwig spent all his royal revenues (although not state funds) on these projects, borrowed extensively, and defied all attempts by his ministers to restrain him. This extravagance was used against him to declare him insane, an accusation which has since been claimed to have been incorrect.[3] Today, his architectural and artistic legacy includes many of Bavaria's most important tourist attractions.

Life

Childhood and adolescent years

Born in Nymphenburg Palace (today located in suburban Munich), he was the elder son of Maximilian II of Bavaria (then Bavarian Crown Prince) of the House of Wittelsbach, and his wife Princess Marie of Prussia. His parents intended to name him Otto, but his grandfather, Ludwig I of Bavaria, insisted that his grandson be named after him, since their common birthday, 25 August, is the feast day of Saint Louis IX of France, patron saint of Bavaria. His younger brother, born three years later, was named Otto.

Like many young heirs in an age when kings governed most of Europe, Ludwig was continually reminded of his royal status. King Maximilian wanted to instruct both of his sons in the burdens of royal duty from an early age.[4] Ludwig was both extremely indulged and severely controlled by his tutors and subjected to a strict regimen of study and exercise. There are some who point to these stresses of growing up in a royal family as the causes for much of his odd behavior as an adult. Ludwig was not close to either of his parents.[5] King Maximilian's advisers had suggested that on his daily walks he might like, at times, to be accompanied by his future successor. The King replied, "But what am I to say to him? After all, my son takes no interest in what other people tell him."[6] Later, Ludwig would refer to his mother as "my predecessor's consort".[6] He was far closer to his grandfather, the deposed and notorious King Ludwig I, who came from a family of eccentrics.

Ludwig's childhood years did have happy moments. He lived for much of the time at Castle Hohenschwangau, a fantasy castle his father had built near the Schwansee (Swan Lake) near Füssen. It was decorated in the Gothic Revival style with many frescoes depicting heroic German sagas. The family also visited Lake Starnberg. As an adolescent, Ludwig became close friends with his aide de camp, Prince Paul, a member of Bavaria's wealthy Thurn und Taxis family. The two young men rode together, read poetry aloud, and staged scenes from the Romantic operas of Richard Wagner. The friendship ended when Paul became engaged in 1866. During his youth Ludwig also initiated a lifelong friendship with his cousin, Duchess Elisabeth in Bavaria, later Empress of Austria.[5]

Early reign

Crown Prince Ludwig had just turned 18 when his father died after a three-day illness, and he ascended the Bavarian throne.[6] Although he was not prepared for high office, his youth and brooding good looks made him popular in Bavaria and elsewhere.[5] He continued the state policies of his father and retained his ministers.

His real interests were in art, music, and architecture. One of the first acts of his reign, a few months after his accession, was to summon Wagner to his court.[5][7] Also in 1864, he laid the foundation stone of a new Court Theatre, now the Staatstheater am Gärtnerplatz (Gärtnerplatz-Theater).

Ludwig was notably eccentric in ways that made serving as Bavaria's head of state problematic. He disliked large public functions and avoided formal social events whenever possible, preferring a life of seclusion that he pursued with various creative projects. He last inspected a military parade on 22 August 1875 and last gave a Court banquet on 10 February 1876.[8] His mother had foreseen difficulties for Ludwig when she recorded her concern for her extremely introverted and creative son who spent much time day-dreaming. These idiosyncrasies, combined with the fact that Ludwig avoided Munich and participating in the government there at all costs, caused considerable tension with the king's government ministers, but did not cost him popularity among the citizens of Bavaria. The king enjoyed traveling in the Bavarian countryside and chatting with farmers and labourers he met along the way. He also delighted in rewarding those who were hospitable to him during his travels with lavish gifts. He is still remembered in Bavaria as "Unser Kini" ("our cherished king" in the Bavarian dialect).

Austro-Prussian War and Franco-Prussian War

Relations with Prussia took center stage from 1866. In the Austro-Prussian War, which began in July, Ludwig supported Austria against Prussia.[5] Austria and Bavaria were defeated; and Bavaria was forced to sign a mutual defense treaty with Prussia. When the Franco-Prussian War broke out in 1870, Bavaria was required to fight alongside Prussia. After the Prussian victory over France, Bismarck moved to complete the Unification of Germany.

In November 1870, Bavaria joined the North German Confederation and thus lost its status as an independent kingdom. However, the Bavarian delegation under Prime Minister Count Otto von Bray-Steinburg secured privileged status for Bavaria within the Empire (Reservatrechte). Bavaria retained its own diplomatic corps and its own army, which would come under Prussian command only in times of war.

In December 1870, Bismarck by certain financial concessions induced Ludwig to write the so-called Kaiserbrief, a letter endorsing the creation of the German Empire with King Wilhelm I of Prussia as Emperor. Nevertheless, Ludwig regretted Bavaria's loss of independence and refused to attend Wilhelm's 10 January proclamation as German Emperor in the Palace of Versailles.[9] Ludwig's brother Prince Otto and his uncle Luitpold went instead.[10][11] Otto criticized the celebration as ostentatious and heartless in a letter to his brother.

Engagement and sexuality

The greatest stress of Ludwig's early reign was pressure to produce an heir. This issue came to the forefront in 1867. Ludwig became engaged to Duchess Sophie Charlotte in Bavaria, his cousin and the youngest sister of his dear friend Elisabeth, Empress of Austria.[5] They shared a deep interest in the works of Wagner. The engagement was announced on 22 January 1867; a few days earlier, Ludwig had written Sophie that "The main substance of our relationship has always been … Richard Wagner's remarkable and deeply moving destiny."[12]

But Ludwig repeatedly postponed the wedding date, and finally cancelled the engagement in October. After the engagement was broken off, Ludwig wrote to his former fiancée, "My beloved Elsa! Your cruel father has torn us apart. Eternally yours, Heinrich." (The names Elsa and Heinrich came from characters in Wagner's opera Lohengrin.)[12] Sophie later married Prince Ferdinand, Duke of Alençon.

Ludwig never married, nor had any known mistresses. It is known from his diary (begun in the 1860s), private letters, and other surviving personal documents, that he had strong homosexual desires. He struggled all his life to suppress his sexual desires and remain true to his Roman Catholic faith.[13] While homosexuality had not been punishable in Bavaria since 1813,[14] the Unification of Germany in 1871 under Prussian hegemony changed this.

Throughout his reign, Ludwig had a succession of close friendships with men, including his chief equerry and Master of the Horse, Richard Hornig (1843–1911), Hungarian theater actor Josef Kainz, and courtier Alfons Weber (born c.1862).

Ludwig's original diaries from 1869 onward were lost during World War II, and all that remain today are copies of entries made during the 1886 plot to depose him. Some earlier diaries have survived in the Geheimes Hausarchiv in Munich, and extracts starting in 1858 were published by Evers in 1986.[15]

Ludwig as patron

After 1871, Ludwig largely withdrew from politics, and devoted himself to his personal creative projects, most famously his castles, where he personally approved every detail of the architecture, decoration, and furnishing.

Ludwig and Wagner

Ludwig was intensely interested in the operas of Richard Wagner. This interest began when Ludwig first saw Lohengrin at the impressionable age of 15½, followed by Tannhäuser ten months later. Wagner's operas appealed to the king's fantasy-filled imagination.

Wagner had a notorious reputation as a political radical and philanderer, and was constantly on the run from creditors.[5] But on 4 May 1864, the 51-year-old Wagner was given an unprecedented 1¾ hour audience with Ludwig in the Royal Palace in Munich; later the composer wrote of his first meeting with Ludwig, "Alas, he is so handsome and wise, soulful and lovely, that I fear that his life must melt away in this vulgar world like a fleeting dream of the gods."[5][7] Ludwig was probably the savior of Wagner's career. Without Ludwig, it is doubtful that Wagner's later operas would have been composed, much less premiered at the prestigious Munich Royal Court Theatre (now the Bavarian State Opera).

A year after meeting the King, Wagner presented his latest work, Tristan und Isolde, in Munich to great acclaim. But the composer's perceived extravagant and scandalous behaviour in the capital was unsettling for the conservative people of Bavaria, and the King was forced to ask Wagner to leave the city six months later, in December 1865.

Ludwig considered abdicating to follow Wagner, but Wagner persuaded him to stay.

Ludwig provided a residence for Wagner in Switzerland. Wagner completed Die Meistersinger there; it was premiered in Munich in 1868. When Wagner returned to his "Ring Cycle", Ludwig demanded "special previews" of the first two works (Das Rheingold and Die Walküre) at Munich in 1869 and 1870.[16]

Wagner however was now planning his great personal opera house at Bayreuth. Ludwig initially refused to support this grandiose project. But when Wagner exhausted all other sources, he appealed to Ludwig, who gave him 100,000 thalers to complete the work. Ludwig attended the dress rehearsal and third public performance of the complete Ring Cycle in 1876.

Ludwig and theater

Ludwig's interest in theater was by no means confined to Wagner. In 1867, he appointed Karl von Perfall as Director of his new court theater. Ludwig wished to introduce Munich theater-goers to the best of European drama. Perfall, under Ludwig's supervision, introduced them to Shakespeare, Calderón, Mozart, Gluck, Ibsen, Weber, and many others. He also raised the standard of interpretation of Schiller, Molière, and Corneille.[17]

Between 1872 and 1885, the King had 209 private performances (Separatvorstellungen) given for himself alone or with a guest, in the two court theaters, comprising 44 operas (28 by Wagner, including eight of Parsifal), 11 ballets, and 154 plays (the principal theme being Bourbon France) at a cost of 97,300 marks.[18] This was not due so much to misanthropy but, as the King complained to the theatre actor-manager Ernst Possart: "I can get no sense of illusion in the theatre so long as people keep staring at me, and follow my every expression through their opera-glasses. I want to look myself, not to be a spectacle for the masses."

Ludwig's castles

Ludwig used his personal fortune (supplemented annually from 1873 by 270,000 marks from the Welfenfonds[19]) to fund the construction of a series of elaborate castles. In 1867 he visited Eugène Viollet-le-Duc's work at Pierrefonds, and the Palace of Versailles in France, as well as the Wartburg near Eisenach in Thuringia, which largely influenced the style of his construction. In his letters, Ludwig marvelled at how the French had magnificently built up and glorified their culture (e.g., architecture, art, and music) and how miserably lacking Bavaria was in comparison. It became his dream to accomplish the same for Bavaria. These projects provided employment for many hundreds of local laborers and artisans and brought a considerable flow of money to the relatively poor regions where his castles were built. Figures for the total costs between 1869 and 1886 for the building and equipping of each castle were published in 1968: Schloß Neuschwanstein 6,180,047 marks; Schloß Linderhof 8,460,937 marks (a large portion being expended on the Venus Grotto); Schloß Herrenchiemsee (from 1873) 16,579,674 marks[20] In order to give an equivalent for the era, the British Pound sterling, being the monetary hegemon of the time, had a fixed exchange rate (based on the gold standard) at £1 = 20.43 Goldmarks.

In 1868, Ludwig commissioned the first drawings for his buildings, starting with Neuschwanstein and Herrenchiemsee, though work on the latter did not commence until 1878.

Neuschwanstein

Schloss Neuschwanstein ("New Swan-on-the-Rock castle") is a dramatic Romanesque fortress with soaring fairy-tale towers. It is situated on an Alpine crag above Ludwig's childhood home, Castle Hohenschwangau (approximately, "High Swan Region"). Hohenschwangau was a medieval knights' castle which his parents had purchased. Ludwig reputedly had seen the location and conceived of building a castle there while still a boy.

In 1869, Ludwig oversaw the laying of the cornerstone for Schloss Neuschwanstein on a breathtaking mountaintop site. The walls of Neuschwanstein are decorated with frescoes depicting scenes from the legends used in Wagner's operas, including Tannhäuser, Tristan und Isolde, Lohengrin, Parsifal, and the somewhat less than mystic Die Meistersinger.[21]

Linderhof

In 1878, construction was completed on Ludwig's Schloss Linderhof, an ornate palace in neo-French Rococo style, with handsome formal gardens. The grounds contained a Venus grotto lit by electricity, where Ludwig was rowed in a boat shaped like a shell. After seeing the Bayreuth performances Ludwig built Hundinghütte ("Hunding's Hut", based on the stage set of the first act of Wagner's Die Walküre) in the forest near Linderhof, complete with an artificial tree and a sword embedded in it. (In Die Walküre, Siegmund pulls the sword from the tree.) Hunding's Hut was destroyed in 1945 but a replica was constructed at Linderhof in 1990. In 1877, Ludwig had Einsiedlei des Gurnemanz (a small hermitage, as seen in the third act of Parsifal) erected near Hunding's Hut, with a meadow of spring flowers. The king would retire to read. (A replica made in 2000 can now be seen in the park at Linderhof.) Nearby a Moroccan House, purchased at the Paris World Fair in 1878, was erected alongside the mountain road. Sold in 1891 and taken to Oberammergau, it was purchased by the government in 1980 and re-erected in the park at Linderhof after extensive restoration. Inside the palace, iconography reflected Ludwig's fascination with the absolutist government of Ancien régime France. Ludwig saw himself as the "Moon King", a romantic shadow of the earlier "Sun King", Louis XIV of France. From Linderhof, Ludwig enjoyed moonlit sleigh rides in an elaborate eighteenth-century sleigh, complete with footmen in eighteenth century livery.

Herrenchiemsee

In 1878, construction began on Herrenchiemsee, a partial replica of the palace at Versailles, sited on the Herreninsel in the Chiemsee. It was built as Ludwig's tribute to Louis XIV of France, the magnificent "Sun King." Only the central portion of the palace was built; all construction halted on Ludwig's death. What exists of Herrenchiemsee comprises 8,366 square metres (90,050 sq ft), a "copy in miniature" compared with Versailles' 551,112 ft².

Munich Residenz Palace Royal apartment

The following year, Ludwig finished the construction of the royal apartment in the Residenz Palace in Munich, to which he had added an opulent conservatory or winter garden on the palace roof. It was started in 1867 as quite a small structure, but after extensions in 1868 and 1871, the dimensions reached 69.5mx17.2mx9.5m high. It featured an ornamental lake complete with skiff, a painted panorama of the Himalayas as a backdrop, an Indian fisher-hut of bamboo, a Moorish kiosk, and an exotic tent. The roof was a technically advanced metal and glass construction. The winter garden was closed in June 1886, partly dismantled the following year and demolished in 1897.[22][23]

Later projects

In the 1880s, Ludwig continued his elaborate schemes.

He planned the construction of a new castle on Falkenstein ("Falcon Rock") near Pfronten in the Allgäu (a place he knew well: a diary entry for 16 October 1867 reads "Falkenstein wild, romantic").[24] The first design was a sketch by Christian Jank in 1883 "very much like the Townhall of Liege".[25] Subsequent designs showed a modest villa with a square tower[26] and a small Gothic castle.[27][28] By 1885, a road and water supply had been provided at Falkenstein but the old ruins remained untouched.[29]

Ludwig also proposed a Byzantine palace in the Graswangtal, and a Chinese summer palace by the Plansee in Tyrol. These projects never got beyond initial plans.

Controversy and struggle for power

Although the king had paid for his pet projects out of his own funds and not the state coffers, that did not necessarily spare Bavaria from financial fallout.[30] By 1885, the king was 14 million marks in debt, had borrowed heavily from his family, and rather than economizing, as his financial ministers advised him, he planned further opulent designs without pause. He demanded that loans be sought from all of Europe's royalty, and remained aloof from matters of state. Feeling harassed and irritated by his ministers, he considered dismissing the entire cabinet and replacing them with fresh faces. The cabinet decided to act first.

Seeking a cause to depose Ludwig by constitutional means, the rebelling ministers decided on the rationale that he was mentally ill, and unable to rule. They asked Ludwig's uncle, Prince Luitpold, to step into the royal vacancy once Ludwig was deposed. Luitpold agreed, on condition the conspirators produced reliable proof that the king was in fact helplessly insane.

Between January and March 1886, the conspirators assembled the Ärztliches Gutachten or Medical Report, on Ludwig's fitness to rule. Most of the details in the report were compiled by Count von Holnstein, who was disillusioned with Ludwig and actively sought his downfall. Holnstein used bribery and his high rank to extract a long list of complaints, accounts, and gossip about Ludwig from among the king's servants. The litany of supposed bizarre behavior included his pathological shyness, his avoidance of state business, his complex and expensive flights of fancy, dining out of doors in cold weather and wearing heavy overcoats in summer, sloppy and childish table manners; dispatching servants on lengthy and expensive voyages to research architectural details in foreign lands; and abusive, violent threats to his servants.

The degree to which these accusations were accurate may never be known. The conspirators approached Bismarck, who doubted the report's veracity, calling it "rakings from the King's wastepaper-basket and cupboards."[31] Bismarck commented after reading the Report that "the Ministers wish to sacrifice the King, otherwise they have no chance of saving themselves." He suggested that the matter be brought before the Bavarian Diet and discussed there, but did not stop the ministers from carrying out their plan.[32]

In early June, the report was finalized and signed by a panel of four psychiatrists: Dr. Bernhard von Gudden, chief of the Munich Asylum; Dr. Hubert von Grashey (who was Gudden's son-in-law); and their colleagues, a Dr. Hagen and a Dr. Hubrich. The report declared in its final sentences that the king suffered from paranoia, and concluded, "Suffering from such a disorder, freedom of action can no longer be allowed and Your Majesty is declared incapable of ruling, which incapacity will be not only for a year's duration, but for the length of Your Majesty's life." The men had never met the king, except for Gudden, only once, twelve years earlier, and none had ever examined him.[5] (Today the claim of paranoia is not considered correct; Ludwig's behavior is rather interpreted as a schizotypal personality disorder and he may also have suffered from Pick's disease during his last years, an assumption supported by a frontotemporal lobar degeneration mentioned in the autopsy report.)[33]

Ludwig's younger brother and successor, Otto, was considered insane,[34] providing a convenient basis for the claim of hereditary insanity.

Questions about the lack of medical diagnosis make the legality of the deposition controversial. Adding to the controversy are the mysterious circumstances under which King Ludwig died. He and the doctor assigned to him in captivity at Berg Castle on Lake Starnberg were both found dead in the lake in waist-high water, the doctor with unexplained injuries to the head and shoulders, the morning after the day Ludwig was deposed.[35] It was claimed that Ludwig had drowned, even though no water was found in his lungs at the autopsy. One of Ludwig's most quoted sayings was "I wish to remain an eternal enigma to myself and to others."[36]

Deposition

At 4 a.m. on 10 June 1886, a government commission including Holnstein and Gudden arrived at Neuschwanstein to deliver the document of deposition to the king formally and to place him in custody. Tipped off an hour or two earlier by a faithful servant, his coachman Fritz Osterholzer, Ludwig ordered the local police to protect him, and the commissioners were turned back at the castle gate at gunpoint. In an infamous sideshow, the commissioners were attacked by the 47-year-old baroness Spera von Truchseß,[37] loyal to the king, who flailed at the men with her umbrella and then rushed to the king’s apartments to identify the conspirators. Ludwig then had the commissioners arrested, but after holding them captive for several hours, released them.

That same day, the Government publicly proclaimed Luitpold as Prince Regent. The king’s friends and allies urged him to flee, or to show himself in Munich and thus regain the support of the people. Ludwig hesitated, instead issuing a statement, allegedly drafted by his aide-de-camp Count Alfred Dürckheim, which was published by a Bamberg newspaper on 11 June:

- The Prince Luitpold intends, against my will, to ascend to the Regency of my land, and my erstwhile ministry has, through false allegations regarding the state of my health, deceived my beloved people, and is preparing to commit acts of high treason. [...] I call upon every loyal Bavarian to rally around my loyal supporters to thwart the planned treason against the King and the fatherland.

The government succeeded in suppressing the statement by seizing most copies of the newspaper and handbills. Anton Sailer's pictorial biography of the King prints a photograph of this rare document. (The authenticity of the Royal Proclamation is doubted however, as it is dated 9 June, before the Commission arrived, it uses "I" instead of the royal "We" and there are orthographic errors.) As the king dithered, his support waned. Peasants who rallied to his cause were dispersed, and the police who guarded his castle were replaced by a police detachment of 36 men who sealed off all entrances to the castle.

Eventually the king decided he would try to escape, but it was too late. In the early hours of 12 June, a second commission arrived. The King was seized just after midnight and at 4 am was taken to a waiting carriage. He asked Dr. Gudden, "How can you declare me insane? After all, you have never seen or examined me before," only to be told that "it was unnecessary; the documentary evidence [the servants' reports] is very copious and completely substantiated. It is overwhelming." [38] Ludwig was transported to Berg Castle on the shores of Lake Starnberg, south of Munich.

Mysterious death

On the afternoon of the next day, 13 June 1886, Dr Gudden accompanied Ludwig on a stroll in the grounds of the castle. They were accompanied by two attendants. On their return Gudden expressed optimism to other doctors concerning the treatment of his royal patient. Following dinner, at around 6 PM, Ludwig asked Gudden to accompany him on a further walk, this time through the Schloß Berg parkland along the shore of Lake Starnberg. Gudden agreed; the walk may even have been his suggestion, and he told the aides not to accompany them. His words were ambiguous (Es darf kein Pfleger mitgehen, "No attendant may come along") and whether they were meant to follow at a discreet distance is not clear. The two men were last seen at about 6:30 PM; they were due back at 8 PM but never returned. After searches were made for more than two hours by the entire castle staff in a gale with heavy rain, at 10:30 PM that night, the bodies of both the King and von Gudden were found, head and shoulders above the shallow water near the shore. The King's watch had stopped at 6:54. Gendarmes patrolling the park had heard and seen nothing.

Ludwig's death was officially ruled a suicide by drowning, but the official autopsy report indicated that no water was found in his lungs.[39][40] Ludwig was a very strong swimmer in his youth, the water was approximately waist-deep where his body was found, and he had not expressed suicidal feelings during the crisis.[39][41] Gudden's body showed blows to the head and neck and signs of strangulation, leading to the suspicion that he was strangled although there is no evidence to prove this.[5]

Many hold that Ludwig was murdered by his enemies while attempting to escape from Berg. One account suggests that the king was shot.[39] The King's personal fisherman, Jakob Lidl (1864–1933), stated, "Three years after the king's death I was made to swear an oath that I would never say certain things — not to my wife, not on my deathbed, and not to any priest … The state has undertaken to look after my family if anything should happen to me in either peacetime or war." Lidl kept his oath, at least orally, but left behind notes which were found after his death. According to Lidl, he had hidden behind bushes with his boat, waiting to meet the king, in order to row him out into the lake, where loyalists were waiting to help him escape. "As the king stepped up to his boat and put one foot in it, a shot rang out from the bank, apparently killing him on the spot, for the king fell across the bow of the boat."[39][42] However, the autopsy report indicates no scars or wounds found on the body of the dead king; on the other hand, many years later Countess Josephine von Wrba-Kaunitz would show her afternoon tea guests a grey Loden coat with two bullet holes in the back, asserting it was the one Ludwig was wearing.[43] Another theory suggests that Ludwig died of natural causes (such as a heart attack or stroke) brought on by the cool water (12 °C) of the lake during an escape attempt.[39]

Ludwig’s remains were dressed in the regalia of the Order of Saint Hubert, and lay in state in the royal chapel at the Munich Residence Palace. In his right hand he held a posy of white jasmine picked for him by his cousin the Empress Elisabeth of Austria.[44] After an elaborate funeral on 19 June 1886, Ludwig's remains were interred in the crypt of the Michaelskirche in Munich. His heart, however, does not lie with the rest of his body. Bavarian tradition called for the heart of the king to be placed in a silver urn and sent to the Gnadenkapelle (Chapel of Mercy) in Altötting, where it was placed beside those of his father and grandfather.

Three years after his death, a small memorial chapel was built overlooking the site and a cross was erected in the lake. A remembrance ceremony is held there each year on 13 June.

The King was succeeded by his brother Otto, but since Otto was considered incapacitated by mental illness due to a "diagnosis" by Dr. Gudden, the king's uncle Luitpold remained regent. Luitpold maintained the regency until his own death in 1912 at the age of 91. He was succeeded as regent by his eldest son, also named Ludwig. The regency lasted for 13 more months until November 1913, when Regent Ludwig deposed the still-living but still-institutionalized King Otto, and declared himself King Ludwig III of Bavaria. His reign lasted until the end of the World War I, when monarchy in all of Germany came to an end.

Legacy

Ludwig was deeply peculiar and irresponsible, but the question of clinical insanity remains unresolved.[35] The prominent German brain researcher Heinz Häfner has disagreed with the contention that there was clear evidence for Ludwig's insanity.[5] Others believe he may have suffered from the effects of chloroform used in an effort to control chronic toothache rather than any psychological disorder. His cousin and friend, Empress Elisabeth held that, "The King was not mad; he was just an eccentric living in a world of dreams. They might have treated him more gently, and thus perhaps spared him so terrible an end."

Today visitors pay tribute to King Ludwig by visiting his grave as well as his castles. Ironically, the very castles which were said to be causing the king’s financial ruin have today become extremely profitable tourist attractions for the Bavarian state. The palaces, given to Bavaria by Ludwig III's son Crown Prince Rupprecht in 1923,[45] have paid for themselves many times over and attract millions of tourists from all over the world to Germany each year.

Buildings

It is not surprising that Ludwig II had a great interest in building. His paternal grandfather, King Ludwig I, had largely rebuilt Munich. It was known as the 'Athens on the Isar'. His father, King Maximilian II had also continued with more construction in Munich as well as the construction of Hohenschwangau Castle, the childhood home of Ludwig II, near the future Neuschwanstein Castle of Ludwig II. Ludwig II had planned to build a large opera house on the banks of the Isar river in Munich. This plan was vetoed by the Bavarian government.[46] Using similar plans, a festival theatre was built later in his reign from Ludwig's personal finances at Bayreuth.

- Winter Garden, Residenz Palace, Munich, an elaborate winter garden built on the roof of the Residenz Palace in Munich. It featured an ornamental lake with gardens and painted frescos. It was roofed over using a technically advanced metal and glass construction.[22] After the death of Ludwig II, it was dismantled in 1897 due to water leaking from the ornamental lake through the ceiling of the rooms below. Photographs and sketches still record this incredible creation which included a grotto, a Moorish kiosk, an Indian royal tent, an artificially illuminated rainbow and intermittent moonlight.[22][47]

- Neuschwanstein Castle,[48] or "New Swan Stone Castle", a dramatic Romanesque fortress with Byzantine, Romanesque and Gothic interiors, which was built high above his father's castle: Hohenschwangau. Numerous wall paintings depict scenes from the legends Wagner used in his operas. Christian glory and chaste love figure predominantly in the iconography, and may have been intended to help Ludwig live up to his religious ideals, but the bedroom decoration depicts the illicit love of Tristan & Isolde (after Gottfried von Strasbourg's poem). The castle was not finished at Ludwig's death; the Kemenate was completed in 1892 but the watch-tower and chapel were only at the foundation stage in 1886 and were never built.[49] The residence quarters of the King – which he first occupied in May 1884[50] – can be visited along with the servant's rooms, kitchens as well as the monumental throne room. Unfortunately the throne was never completed although sketches show how it might have looked on completion.[51]

Neuschwanstein Castle is a landmark well known by many non-Germans, and was used by Walt Disney in the twentieth century as the inspiration for the Sleeping Beauty Castles at Disney Parks around the world. The castle has had over 50 million visitors since it was opened to the public on 1 August 1886, including 1.3 million in 2008 alone.[52]

- Linderhof Castle, an ornate palace in neo-French Rococo style, with handsome formal gardens. Just north of the palace, at the foot of the Hennenkopf, the park contains a Venus grotto where Ludwig was rowed in a shell-like boat on an underground lake lit with red, green or "Capri" blue effects by electricity, a novelty at that time, provided by one of the first generating plants in Bavaria.[53] Stories of private musical performances here are probably apochryphal; nothing is known for certain.[54] In the forest nearby a romantic wooded hut was also built around an artificial tree (see Hundinghütte above). Inside the palace, iconography reflects Ludwig's fascination with the absolutist government of Ancien Régime France. Ludwig saw himself as the "Moon King", a romantic shadow of the earlier "Sun King", Louis XIV of France. From Linderhof, Ludwig enjoyed moonlit sleigh rides in an elaborate eighteenth century sleigh, complete with footmen in eighteenth century livery. He was known to stop and visit with rural peasants while on rides, adding to his legend and popularity. The sleigh can today be viewed with other royal carriages and sleds at the Carriage Museum (Marstallmusem) at Nymphenburg Palace in Munich. Its lantern was illuminated by electricity supplied by a battery.[55] There is also a Moorish Pavilion in the park of Schloß Linderhof.[56]

- Herrenchiemsee, a replica (although only the central section was ever built) of Louis XIV of France's Palace of Versailles, France, which was meant to outdo its predecessor in scale and opulence – for instance, at 98 meters the Hall of Mirrors and its adjoining Halls of War and Peace is slightly longer than the original. The palace is located on the Herren Island in the middle of the Chiemsee Lake. Most of the palace was never completed once the king ran out of money, and Ludwig lived there for only 10 days in October 1885, less than a year before his mysterious death.[50] It is interesting to note that tourists come from France to view the recreation of the famous Ambassadors' Staircase. The original Ambassadors' Staircase at Versailles was demolished in 1752.[57]

- Ludwig also outfitted Schachen king's house with an overwhelmingly decorative Oriental style interior, including a replica of the famous Peacock Throne.

- Falkenstein, a planned, but never executed "robber baron's castle" in the Gothic style. A painting by Christian Jank shows the proposed building as an even more fairytale version of Neuschwanstein, perched on a rocky cliff high above Castle Neuschwanstein.

Ludwig II left behind a large collection of plans and designs for other castles that were never built, as well as plans for further rooms in his completed buildings. Many of these designs are housed today in the King Ludwig II Museum at Herrenchiemsee Castle. These building designs date from the latter part of the King's reign, beginning around 1883. As money was starting to run out, the artists knew that their designs would never be executed. The designs became more extravagant and numerous as the artists realized that there was no need to concern themselves with economy or practicality.

| ||||||||||||||

Ludwig and the arts

It has been said that Richard Wagner’s late career is part of Ludwig’s legacy, since he almost certainly would have been unable to complete his opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen or to write his final opera, Parsifal, without the king’s support.

Ludwig also sponsored the premieres of Tristan und Isolde, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, and, through his financial support of the Bayreuth Festival, those of Der Ring des Nibelungen and Parsifal.[58]

Ludwig provided Munich with its Staatstheater am Gärtnerplatz, establishing a lasting tradition of performing the best of European drama.

In popular culture

Video Games

- The Beast Within: A Gabriel Knight Mystery (1995) – Released by Sierra On-Line

Board Games

- Castles of Mad King Ludwig (2014) - Released by Bezier Games and designed by Ted Alspach [59]

Film

- Ludwig II (1922), a silent Austrian film directed by Otto Kreisler and starring Olaf Fjord as Ludwig

- Ludwig II, King of Bavaria (1929), a late German silent film directed by and starring William Dieterle

- Ludwig II: Glanz und Ende eines Königs (1955), a West German film directed by Helmut Käutner and starring O. W. Fischer as Ludwig and Ruth Leuwerik as Empress Elizabeth

- Ludwig (1972), a film directed by Luchino Visconti which traces the life of Ludwig II from his accession to death, and stars Helmut Berger as Ludwig II and Romy Schneider as the Austrian Empress Elisabeth.

- The 1972 German film Ludwig - Requiem für einen jungfräulichen König (Ludwig – Requiem for a Virgin King), written and directed by Hans-Jürgen Syberberg provides a more personal, sympathetic, and idiosyncratic account of the King's life from boyhood to death, and stars Harry Baer and Balthasar Thomass as Ludwig II, and Gerhard Maerz as Richard Wagner.

- An epic film, Wagner (1983), directed by Tony Palmer, on the life of Richard Wagner, starring Richard Burton in the title role, also features László Gálffi in the substantial role of King Ludwig.

- In the 1993 film Ludwig 1881, Helmut Berger reprises his role as Ludwig II in an episode involving the actor Josef Kainz, who is invited to accompany the king on a cruise on a Swiss lake, in order to recreate scenes from a story that actually took place around the lake.

- Ludwig II (2012 film) (2012), directed by Peter Sehr and Marie Noelle, and starring Sabin Tambrea as the younger Ludwig and Sebastian Schipper as the king in his later years.

Literature

- The three-volume manga series Ludwig II (ルートヴィヒII世) by the artist You Higuri, published by Kadokawa Shoten, is a highly fictionalized account of Ludwig's love life.

- Sharyn McCrumb's 1984 mystery novel Sick of Shadows features a character who identifies with Ludwig II and builds a replica of Neuschwanstein castle in Georgia. The novel also acts out a few more disturbing incidents from Ludwig's life.

- The story of Ludwig II is discussed by the characters of the 1947 novel Doktor Faustus by Thomas Mann, in chapter XL.

- Ludwig is the central character in the novel Remember Me (1957) by the American David Stacton (1923–1968).[60] The novel, part of a triptych dealing with "The Invincible Questions"[61] concentrates on Ludwig's psychology, including his notion of kingship, his homoerotic relationships, and his reasons for building; Stacton represents Ludwig's death as a suicide.

- Chris Kuzneski's book, The Secret Crown, involves his main characters going through the life of Ludwig II to discover his secret palace.

- The Ludwig Conspiracy(2013) by Oliver Pötzsch is a thriller about a conspiracy around the murder of King Ludwig.

Music

- Illusions like 'Swan Lake, a restaging of Tchaikovsky's ballet Swan Lake by John Neumeier to reflect the life of Ludwig II.

- A number of musicals based on the life of Ludwig II have been staged. One was called, Ludwig: The Musical by Rolf Rettburg and another, Ludwig II: Longing For Paradise with music by Franz Hummel and lyrics by Stephen Barbarino. A special theatre was constructed on the shores of the lake at Fussen, not far from Castles Hohenschwangau and Neuschwanstein, specifically for the musical performances.

Ancestors

.jpg)

Titles and styles

- 25 August 1845 – 28 March 1848 His Royal Highness Prince Ludwig of Bavaria

- 28 March 1848 – 10 March 1864 His Royal Highness The Crown Prince of Bavaria

- 10 March 1864 – 13 June 1886 His Majesty The King of Bavaria

References

Notes

- ↑ At 00.28 hours: J.G. Wolf 1922, p. 16. Compare Ludwig's remark to Anton Niggl on 11/12 June 1886 about being born and going to die at 12.30 (Hacker 1966, p. 363 quoting Gerold 1914, pp. 91-3)

- ↑ Adreßbuch von München 1876, p. 1.

- ↑ "Mad King Ludwig? Study Claims Bavarian Monarch Was Sane". Der Spiegel. Hamburg. 31 January 2014. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ↑ Nohbauer, 1998, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Der Mythos vom Märchenkönig". focus.de. 2010-06-12. Retrieved 2011-06-14.

- 1 2 3 Nohbauer, 1998, p. 12.

- 1 2 Nohbauer, 1998, p. 25.

- ↑ Hojer 1986, p. 138

- ↑ Nohbauer, 1998, p. 37.

- ↑ Toeche-Mittler, Dr. Theodor. Die Kaiserproklamation in Versailles am 18. Januar 1871 mit einem Verzeichniß der Festtheilnehmer, Ernst Siegfried Mittler und Sohn, Berlin, 1896

- ↑ Schnaebeli, H. Fotoaufnahmen der Kaiserproklamation in Versailles, Berlin, 1871

- 1 2 Nohbauer, 1998, p. 40.

- ↑ McIntosh, 1982, pp. 155–158.

- ↑ Till 2010, p. 48

- ↑ Evers, Hans Gerhard. Ludwig II. von Bayern. Theaterfürst-König-Bauherr (Munich, 1986)

- ↑ Millington, Barry (ed.) (2001), The Wagner Compendium: A Guide to Wagner's Life and Music (revised edition), London: Thames and Hudson Ltd. ISBN 0-02-871359-1. pp 287, 290

- ↑ Rall, Petzet and Merta (2001) King Ludwig II

- ↑ See Hommel, Kurt. Die Separatvorstellungen vor König Ludwig II. von Bayern (Munich, 1963)

- ↑ Hojer, Gerhard (ed.) König Ludwig II.-Museum Herrenchiemsee. Katalog (Munich, 1986, p. 137)

- ↑ Petzet Katalog 1968, p. 226.

- ↑ "The pictures in the new castle shall follow the sagas and not Wagner's interpretation of them." Letter from footman Adalbert Welker to Court secretary Ludwig von Bürkel, 5 April 1879 (Petzet 1970, p. 138)

- 1 2 3 Nohbauer, 1998, p. 18.

- ↑ See Die Wintergarten König Ludwigs II. in der Münchener Residenz by Elmar D. Schmid in Gerhard Hojer (ed.): König Ludwig II. Museum Herrenchiemsee. Katalog. (Munich, 1986), pp. 62-94 & 446-451.

- ↑ Evers 1986, p. 228.

- ↑ Kreisel 1954, p. 82

- ↑ Dollmann 1884

- ↑ Schultze 1884, Hofmann 1886

- ↑ See Petzet Katalog 1968 & Hojer 1986, pp. 298-304 for details.

- ↑ Hojer 1986, p. 300.

- ↑ Nohbauer, 1998, p. 73.

- ↑ Blunt, Wilfrid; Petzet, Michael (1 December 1970). Dream King: Ludwig II of Bavaria. The Viking Press, Inc. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-670-28456-6.

- ↑ http://schwangau.de/646.0.html

- ↑ Prof. Hans Förstl, "Ludwig II. von Bayern – schizotype Persönlichkeit und frontotemporale Degeneration?", in: Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift, Nr. 132/2007

- ↑ Arndt Richter: Die Geisteskrankheit der bayerischen Könige Ludwig II. und Otto. Eine interdisziplinäre Studie mittels Genealogie, Genetik und Statistik, Degener & Co., Neustadt an der Aisch, 1997, ISBN 3-7686-5111-8

- 1 2 Desing, 1996.

- ↑ "Ein ewig Rätsel bleiben will ich mir und anderen." In a letter dated 27 April 1876 to the actress Marie Dahn-Hausmann (1829–1909), whom Ludwig may have regarded as a kind of substitute mother (published by Conrad in Die Propyläen 17, Munich, 9 July 1920). The words are based on a passage in Schiller's 1803 drama Die Braut von Messina II/1.

- ↑ Esperanza Truchsess von Wetzhausen née Esperanza von Sarachaga, of Spanish descent, born Petersburg 1839, married 1862 Friedrich Truchsess von Wetzhausen (1825–94); died after 1909. Böhm, Gottfried, Ritter von. Ludwig II König von Bayern: sein Leben und seine Zeit. 1922, p. 600. (German)

- ↑ name=nohbauer82

- 1 2 3 4 5 Nohbauer, 1998, p. 88.

- ↑ von Burg, 1989, p. 308.

- ↑ von Burg, 1989, p. 315.

- ↑ von Burg, 1989, p. 311.

- ↑ SPIEGEL ONLINE, Hamburg, Germany (7 November 2007). "Fresh Doubt About Suicide Theory: Was 'Mad' King Ludwig Murdered?". SPIEGEL ONLINE.

- ↑ Nohbauer, 1998, p. 86.

- ↑ "Princess Irmingard of Bavaria". The Daily Telegraph (London). 8 November 2010.

- ↑ Petzet and Neumeister, 1995, p. 24.

- ↑ Calore, 1998, pp. 164-165.

- ↑ First so-called only in 1891: Baumgartner 1981, p. 78

- ↑ Hojer 1986, p. 294

- 1 2 Merta 2005, p. 190

- ↑ Calore, 1998, p. 89.

- ↑ Till 2010, p. 34

- ↑ Petzet 1970, p. 144

- ↑ Petzet 1970, p. 146

- ↑ Petzet 1968, no. 780

- ↑ Katrin Bellinger Master Drawings: "Moroccan House", near the Moorish Pavilion, Linderhof. Watercolor by Heinrich Breling

- ↑ Calore, 1998, p. 60.

- ↑ See Detta & Michael Petzet 1970, passim

- ↑ "Castles of Mad King Ludwig - Board Game - BoardGameGeek". boardgamegeek.com.

- ↑ David Stacton, "Remember Me" [reprint London: Faber and Faber, 2012]

- ↑ Hal Jensen, "David Stacton's Invincible Questions" TLS (the-tls.co.uk, published 3 April 2013)

Bibliography

- English-language biographies and related information on Ludwig II

- Blunt, Wilfred; Petzet, Michael. The Dream King: Ludwig II of Bavaria. (1970) ISBN 0-241-11293-1, ISBN 0-14-003606-7.

- von Burg, Katerina. Ludwig II of Bavaria. (1989) ISBN 1-870417-02-X.

- Calore, Paola. Past and Present Castles of Bavaria. (1998) ISBN 1-84056-019-3.

- Chapman-Huston, Desmond. Bavarian Fantasy: The Story of Ludwig II. (1955) (Much reprinted but not entirely reliable; the author died before completing the biography.)

- Philippe Collas, Louis II de Bavière et Elisabeth d'Autriche, âmes sœurs, Éditions du Rocher, Paris/Monaco 2001) (ISBN 9782268038841)

- King, Greg. The Mad King: The Life and Times of Ludwig II of Bavaria. (1996) ISBN 1-55972-362-9.

- McIntosh, Christopher. The Swan King: Ludwig II of Bavaria. (1982) ISBN 1-86064-892-4.

- Nöhbauer, Hans. Ludwig II. (Taschen, 1998) ISBN 3-8228-7430-2.

- Rall, Hans; Petzet, Michael; Merta, Franz. King Ludwig II. Reality and Mystery. (Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg, 2001. ISBN 3-7954-1427-X (This English translation of König Ludwig II. Wirklichkeit und Rätsel is based on the 1980 German edition, despite revisions contained in the 1986 and subsequent German editions. Includes an itinerary by Merta of Ludwig's travels 1864–86. Rall [1912-98] was formerly Chief Archivist of the Geheimes Hausarchiv in Munich.)

- Richter, Werner. The Mad Monarch: The Life and Times of Ludwig II of Bavaria. (Chicago, 1954; 280 pages; abridged translation of German biography)

- Spangenberg, Marcus: Ludwig II - A Different Kind of King (Regensburg, 2015; 175 pages; translation Margaret Hiley, Oakham, Rutland) ISBN 978-3-7917-2744-8

- Spangenberg, Marcus: The Throne Room in Schloss Neuschwanstein: Ludwig II of Bavaria and his vision of Divine Right (1999) ISBN 978-3-7954-1233-3

- Wrba, Ernst (photos) & Kühler, Michael (text). The Castles of King Ludwig II. (Verlagshaus Würzburg, 2008; 128 richly illustrated pages.) ISBN 978-3-8003-1868-1

- Merkle, Ludwig: Ludwig II and his Dream Castles (Stiebner Verlag, Munich, 2nd edition 2000; 112 pages, 27 colour & 35 monochrome illus., 28.5 x 24.5 cm) ISBN 978-3-8307-1019-6

- Krückmann, Peter O.: The Land of Ludwig II: the Royal Castles and Residences in Upper Bavaria and Swabia (Prestel Verlag, Munich, 2000; 64 pages, 96 colour illus, 23 x 30 cm) ISBN 3-7913-2386-5

- Till, Wolfgang: Ludwig II King of Bavaria: Myth and Truth (Vienna, Christian Brandstätter Verlag, 2010: 112 pages, 132 illus., 21 cm: Engl. edition of Ludwig II König von Bayern: Mythos und Wahrheit [2010]) ISBN 978-3-85033-458-7 (The author was formerly Director of the Munich Civic Museum)

- German-language biographies and related information on Ludwig II

- Botzenhart, Christof: Die Regierungstätigkeit König Ludwig II. von Bayern - "ein Schattenkönig ohne Macht will ich nicht sein" (München, Verlag Beck, 2004, 234 S.) ISBN 3-406-10737-0.

- Design, Julius: Wahnsinn oder Verrat – war König Ludwig II. von Bayern geisteskrank? (Lechbruck, Verlag Kienberger, 1996)

- Hojer, Gerhard: König Ludwig II. - Museum Herrenchiemsee (München, Hirmer Verlag, 1986) ISBN 3-7774-4160-0.

- Petzet, Michael: König Ludwig und die Kunst (Prestel Verlag, München, 1968) (Exhibition catalogue)

- Petzet, Detta und Michael: Die Richard Wagner-Bühne Ludwigs II. (München, Prestel-Verlag, 1970: 840 pages, over 800 illus., 24.5x23cm) (Even for the non-German reader this is an important source of illustrations of designs, stage settings & singers in the early productions of Wagner's operas at Munich & Bayreuth.)

- Petzet, Michael; Neumeister, Werner: Ludwig II. und seine Schlösser: Die Welt des Bayerischen Märchenkönigs (Prestel Verlag, München, 1995) ISBN 3-7913-1471-8. (New edition of 1980 book.)

- Reichold, Klaus: König Ludwig II. von Bayern – zwischen Mythos und Wirklichkeit, Märchen und Alptraum; Stationen eines schlaflosen Lebens (München, Süddeutsche Verlag, 1996)

- Richter, Werner: Ludwig II., König von Bayern (1939; frequently reprinted: 14. Aufl.; München, Stiebner, 2001, 335 S.) ISBN 3-8307-1021-6. (See above for English translation. Richter 1888–1969 was a professional biographer of great integrity.)

- Schäffler, Anita; Borkowsky, Sandra; Adami, Erich: König Ludwig II. von Bayern und seine Reisen in die Schweiz – 20. Oktober – 2. November 1865, 22. Mai – 24. Mai 1866, 27. Juni – 14. Juli 1881; eine Dokumentation (Füssen, 2005)

- Wolf, Georg Jacob (1882–1936): König Ludwig II. und seine Welt (München, Franz Hanfstaengl, 1922; 248 pages, many monochrome illus., 24 cm)

- Spangenberg, Marcus: Ludwig II. - Der andere König (Regensburg, ³2015; 175 pages) ISBN 978-3-7917-2308-2

- Spangenberg, Marcus: Der Thronsaal von Schloss Neuschwanstein: König Ludwig II. und sein Verständnis vom Gottesgnadentum (1999) ISBN 978-3-7954-1225-8

- Rupert Hacker: Ludwig II. von Bayern in Augenzeugenberichten. (1966, 471 pages) (A valuable anthology of published & archival material, compiled by the Director of the Bavarian Civil Service College.)

- Wilhelm Wöbking: Der Tod König Ludwigs II. von Bayern. (Rosenheimer Verlagshaus, 1986, 414 pages) (Includes many documents from the Bavarian State Archives.)

- Schlimm, Jean Louis: König Ludwig II. Sein leben in Bildern und Memorabilien (Nymphenburger, München, 2005; 96 pages, many illus., 24 x 24 cm) ISBN 3-485-01066-9

- Rall, Hans; Petzet, Michael; & Merta, Franz: König Ludwig II. Wirklichkeit und Rätsel (Regensburg, Schnell & Steiner, 3rd edition 2005: 192 pages, 22 colour & 52 monochrome illus., 22.5x17cm) ISBN 3-7954-1426-1

- Nöhbauer, Hans F.: Auf den Spuren König Ludwigs II. Ein Führer zu Schlössern und Museen, Lebens- und Errinerungsstätten des Märchenkönigs. (München, Prestel Verlag, 3rd edition 2007: 240 pages, 348 illus, with plans & maps, 24x12cm) ISBN 978-3-7913-4008-1

- Baumgartner, Georg: Königliche Träume: Ludwig II. und seine Bauten. (München, Hugendubel, 1981: 260 pages, lavishly illustrated with 440 designs, plans, paintings & historic photos.; 30.5 x 26 cm) ISBN 3-88034-105-2

- Oliver Hilmes: Ludwig II. Der unzeitgemäße König, (Siedler Verlag, München), 1st edition October 2013: 447 pages (the first biographer with exclusive access to the private archives of the House of Wittelsbach), ISBN 978-3-88680-898-4

External links

- The romance of King Ludwig II. of Bavaria; his relations with Wagner and his Bavarian fairy places by Frances A Gerard 1901 English

- Ludwig the Second, king of Bavaria by Clara Tschudi 1908 English

- A royal recluse; memories of Ludwig II. of Bavaria by Werner Bertram b. 1900 English

- BBC R4 Great Lives programme on Ludwig – listen online: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b018gpdg

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ludwig II of Bavaria. |

- The 125th Anniversary of the Death of King Ludwig II, photo essay by Alan Taylor, "In Focus", The Atlantic, June 13, 2011

- Mysterious death of King Ludwig

- Ludwig II of Bavaria: Life and Castles

- New theory about the possible murder of Ludwig II

- Video on YouTube of the ballet Illusions – like “Swan Lake”

| Ludwig II of Bavaria Born: 25 August 1845 Died: 13 June 1886 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Maximilian II |

King of Bavaria 1864-1886 |

Succeeded by Otto |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||

|