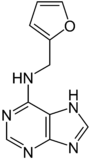

Kinetin

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

N6-furfuryladenine | |

| Identifiers | |

| 525-79-1 | |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:27407 |

| ChemSpider | 3698= |

| EC Number | 208-382-2 |

| Jmol interactive 3D | Image |

| KEGG | C08272 |

| PubChem | 3830 |

| RTECS number | AU6270000 |

| UNII | P39Y9652YJ |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C10H9N5O | |

| Molar mass | 215.22 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Off-white amorphous powder |

| Melting point | 269–271 °C (516–520 °F; 542–544 K) (decomposes) |

| Structure | |

| cubic | |

| Hazards | |

| S-phrases | S22 S24/25 |

| Related compounds | |

| Related |

cytokinin |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

Kinetin is a type of cytokinin, a class of plant hormone that promotes cell division. Kinetin was originally isolated by Miller[1] and Skoog et al.[2] as a compound from autoclaved herring sperm DNA that had cell division-promoting activity. It was given the name kinetin because of its ability to induce cell division, provided that auxin was present in the medium. Kinetin is often used in plant tissue culture for inducing formation of callus (in conjunction with auxin) and to regenerate shoot tissues from callus (with lower auxin concentration).

For a long time, it was believed that kinetin was an artifact produced from the deoxyadenosine residues in DNA, which degrade on standing for long periods or when heated during the isolation procedure. Therefore, it was thought that kinetin does not occur naturally, but, since 1996, it has been shown by several researchers that kinetin exists naturally in the DNA of cells of almost all organisms tested so far, including human and various plants. The mechanism of production of kinetin in DNA is thought to be via the production of furfural — an oxidative damage product of deoxyribose sugar in DNA — and its quenching by the adenine base's converting it into N6-furfuryladenine, kinetin.

Kinetin is also widely used in producing new plants from tissue cultures.

History

In 1939 P. A. C. Nobécourt (Paris) began the first permanent callus culture from root explants of carrot (Daucus carota). Such a culture can be kept forever by successive transplantations onto fresh nutrient agar. The transplantations occur every three to eight weeks. Callus cultures are not cell cultures, since whole tissue associations are cultivated. Though many cells keep their ability to divide, this is not true for all. One reason for this is the aneuploidy of the nuclei and the resultant unfavourable chromosome constellations.

In 1941 J. van Overbeek (Rijksuniversiteit Utrecht) introduced coconut milk as a new component of nutrient media for callus cultures.[3] Coconut milk is liquid endosperm. It stimulates the embryo to grow when it is supplied with food at the same time. Results yielded from callus cultures showed that its active components stimulate the growth of foreign cells too.

In 1954 F. Skoog (University of Wisconsin, Madison) developed a technique for the generation and culture of wound tumor tissue from isolated shoot parts of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum). The developing callus grows when supplied with yeast extract, coconut milk, or old DNA preparations. Freshly prepared DNA has no effect but becomes effective after autoclaving. This led to the conclusion that one of its breakdown products is required for cell growth and division. The substance was characterized, was given the name kinetin, and classified as a phytohormone.

See also

References

- ↑ Schwartz, Dale. "Carlos O. Miller" (pdf). Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- ↑ Amasino, R. (2005). "1955: Kinetin Arrives. The 50th Anniversary of a New Plant Hormone". Plant Physiology 138 (3): 1177–1184. doi:10.1104/pp.104.900160. PMC 1176392. PMID 16009993.

- ↑ Van Overbeek, J.; Conklin, M. E.; Blakeslee, A. F. (1941). "Factors in Coconut Milk Essential for Growth and Development of Very Young Datura Embryos". Science 94 (2441): 350–1. doi:10.1126/science.94.2441.350. PMID 17729950.

- Mok, David W.S.; Mok, Machteld C., eds. (1994). Cytokinins: chemistry, activity and function. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-6252-1.

- Barciszewski, J.; Siboska, G. E.; Pedersen, B. O.; Clark, B. F.; Rattan, S. I. (1996). "Evidence for the presence of kinetin in DNA and cell extracts". FEBS Letters 393 (2–3): 197–200. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(96)00884-8. PMID 8814289.

- Barciszewski, J.; Rattan, S. I. S.; Siboska, G.; Clark, B. F. C. (1999). "Kinetin — 45 years on". Plant Science 148: 37. doi:10.1016/S0168-9452(99)00116-8.

- Rattan, S. I. S.; Clark, B. F. C. (1994). "Kinetin Delays the Onset of Aging Characteristics in Human Fibroblasts". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 201 (2): 665–672. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1994.1752. PMID 8003000.

- Rattan, S. I. S. (2002). "N6-Furfuryladenine (Kinetin) as a Potential Anti-Aging Molecule". Journal of Anti-Aging Medicine 5: 113–111. doi:10.1089/109454502317629336.

- Hertz, Nicholas T.; Berthet, Amandine; Sos, Martin L.; Thorn, Kurt S.; Burlingame, Al L.; Nakamura, Ken; Shokat, Kevan M. "A Neo-Substrate that Amplifies Catalytic Activity of Parkinson’s-Disease-Related Kinase PINK1". Cell 154 (4): 737–747. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.030.