Kihansi spray toad

| Wikispecies has information related to: Nectophrynoides asperginis |

| Kihansi spray toad | |

|---|---|

| |

| Kihansi spray toad at the Toledo Zoo | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Anura |

| Family: | Bufonidae |

| Genus: | Nectophrynoides |

| Species: | N. asperginis |

| Binomial name | |

| Nectophrynoides asperginis Poynton, Howell, Clarke & Lovett, 1999 | |

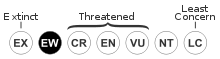

The Kihansi spray toad, Nectophrynoides asperginis, is a small toad endemic to Tanzania.[2][3] The species is live-bearing and insectivorous.[2] The Kihansi spray toad is currently categorized as "Extinct in the wild" by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), though the species persists in ex situ, captive breeding populations.

Physiology

The Kihansi spray toad is a small, sexually dimorphic anuran, with females reaching up to 2.9 cm (1.1 in) long and males up to 1.9 cm (0.75 in).[2] The toads display yellow skin coloration with brownish dorsolateral striping. [4] Females are often duller in coloration, and males normally have more significant markings [5] Additionally, males exhibit dark inguinal patches on their sides where their hind legs meet their abdomens.[5] Abdominal skin is translucent, and developing offspring can often be seen in the bellies of gravid females.[5]

These toads have webbed toes on their hind legs,[5][4] but lack expanded toe tips.[4] They lack external ears, but do possess normal anuran inner ear features, with the exception of tympanic membranes and air-filled middle ear cavities.[6]

Habitat

Prior to its extirpation, the Kihansi spray toad was endemic only to a two hectare area at the base of the Kihansi River waterfall in the Udzungwa escarpment of the Eastern Arc Mountains in Tanzania.[7] The Kihansi Gorge is about 4 km long with a north-south orientation.[4] A number of wetlands made up the habitat of this species, all fed by spray from the Kihansi River waterfall.[4] These wetlands were characterized by dense, grassy vegetation including Panicum grasses, Selaginella kraussiana moss, and snail ferns (Tectaria gemmifera).[4] Areas within the spray zones of the waterfall experienced near-constant temperatures and 100% humidity.[4]

Extinction in the wild

The extinction in the wild of the Kihansi spray toad was mainly due to habitat loss following the construction of Kihansi Dam in 1999, which reduced the amount of water coming down from the waterfall into the gorge by 90 percent.[1] This led to the spray toad's microhabitat being compromised, as it reduced the amount of water spray, which the toads were reliant on. A sprinkler system that mimicked the natural water spray was not yet operational when the Kihansi Dam opened.[1] In 2003 there was a final population crash in the species. This coincided with a breakdown of the sprinkler system during the dry season, the appearance of the disease chytridiomycosis, and the brief opening of the Kihansi Dam to flush out sediments, which contained pesticides.[1] The last confirmed record of wild Kihansi spray toads was in 2004.[1]

Survival in captivity

The Bronx Zoo initiated a project where almost 500 Kihansi spray toads were taken from their native gorge in 2001 and placed in six U.S. zoos as a possible hedge against extinction.[8][9][10] Initially its unusual life style and reproduction mode caused problems in captivity, and only Bronx Zoo and Toledo Zoo were able to maintain populations.[9] By December 2004, less than 70 remained in captivity, but when their exact requirements were discovered greater survival and breeding success was achieved.[8][9] In November 2005, the Toledo Zoo opened an exhibit for the Kihansi spray toad, and for some time this was the only place in the world where it was on display to the public.[8] The Toledo Zoo now has several thousand Kihansi spray toads,[8][11] the majority off-exhibit. The Bronx Zoo also has several thousand Kihansi spray toads,[11] and it opened a small exhibit for some of these in February 2010.[9][12] In 2010 Toledo Zoo transferred 350 toads to Chattanooga Zoo,[8] which has created a small exhibit for them. Groups numbering in the hundreds are now also maintained at Detroit Zoo and Omaha's Henry Doorly Zoo.[11]

Reintroduction

In August 2010, a group of 100 Kihansi spray toads were flown from the Bronx Zoo and Toledo Zoo to their native Tanzania,[8] as part of an effort to reintroduce the species into the wild, using a propagation center at the University of Dar es Salaam.[10][13] In 2012, scientists from the center returned a test population of 48 toads to the Kihansi gorge, having found means to co-inhabit the toads with the chytrid fungus. They plan to release a total population of about 1,800 toads after monitoring the initial release for several months.[14]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Channing, A., Howell, K., Loader, S., Menegon, M. & Poynton, J. (2009). "Nectophrynoides asperginis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- 1 2 3 Channing and Howell. (2006). Amphibians of East Africa. Pp. 106-107. ISBN 3-930612-53-4

- ↑ Frost, Darrel R. (2015). "Nectophrynoides asperginis Poynton, Howell, Clarke, and Lovett, 1999". Amphibian Species of the World: an Online Reference. Version 6.0. American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Channing, A., Finlow-Bates, S., Haarklau S.E., and Hawkes P.G. (2006). "The biology and recent history of the critically endangered Kihansi Spray Toad Nectophrynoides asperginis in Tanzania". Journal of East African Natural History 95 (2): 117–138. doi:10.2982/0012-8317(2006)95[117:tbarho]2.0.co;2.

- 1 2 3 4 Lee, S., Zippel, K., Ramos, L., and Searle, J. (2006). "Captive-breeding program for the Kihansi spray toad Nectophrynoides asperginis at the Wildlife Conservation Society, Bronx, New York". International Zoo Yearbook 40: 241–253. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1090.2006.00241.x.

- ↑ Arch, V.S., Richards-Zawaki, C.L., and Feng, A.S. (2011). "Acoustic communication in the Kihansi spray toad (Nectophrynoides asperginis): Insights from a captive population". Journal of Herpetology 45 (1): 45–49. doi:10.1670/10-084.1.

- ↑ Menegon, M., S. Salvidio, and S.P. Loader (2004). "Five new species of Nectophrynoides Noble 1926 (Amphibia Anura Bufanidae) from the Eastern Arc Mountains, Tanzania". Tropical Zoology 17: 97–121. doi:10.1080/03946975.2004.10531201.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "TZ to Tanzania: A Kihansi Spray Toad Fact Sheet". Toledo Zoo. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 New York Times (1 February 2010). Saving Tiny Toads Without a Home. Accessed 8 January 2012.

- 1 2 Science Daily (17 August 2010). Kihansi Spray Toads Make Historic Return to Tanzania. Accessed 8 January 2011.

- 1 2 3 ISIS (2012). Nectophrynoides asperginis. Version 23 December 2011. Accessed 8 January 2012.

- ↑ World Conservation Society (2 February 2010). Extinct toad in the wild on exhibit at WCS's Bronx zoo. Accessed 8 January 2011

- ↑ Rhett A. Butler (4 September 2008). "Yellow toad births offer hope for extinct-in-the-wild species". mongabay.com. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ↑ Tanzania: Kihansi Toads Pass Anti-Fungal 'Test', by Abdulwakil Saiboko, Tanzania Daily News, 14 August 2012.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to: Nectophrynoides asperginis |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nectophrynoides asperginis. |