Khanate of Kokand

| Khanate of Kokand | |||||

| خانات خوقند Qo'qon Xonligi | |||||

| |||||

|

| |||||

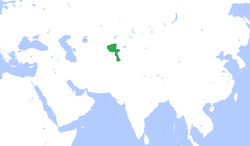

The Khanate of Kokand (green), c. 1850. | |||||

| Capital | Kokand | ||||

| Languages | Uzbek, Persian[1] | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||

| Khan | |||||

| • | 1709-1721 | Shahrukh Biy | |||

| • | 1875-1876 | Nasr ad-Din Abdul Karin Khan | |||

| History | |||||

| • | Established | 1709 | |||

| • | Disestablished | 1876 | |||

| Today part of | | ||||

The Khanate of Kokand (Uzbek: Qo'qon Xonligi, Persian: خانات خوقند) was a Central Asian[2] state that existed from 1709–1876 within the territory of modern Kyrgyzstan, eastern Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, and southeastern Kazakhstan. The name of the city and the khanate may also be spelled as Khoqand in modern scholarly literature.

History

The Khanate of Kokand was established in 1709 when the Shaybanid emir Shahrukh, of the Ming Tribe of Uzbeks, declared independence from the Khanate of Bukhara, establishing a state in the eastern part of the Fergana Valley. He built a citadel as his capital in the small town of Kokand, thus starting the Khanate of Kokand. His son, Abd al-Karim, and grandson, Narbuta Beg, enlarged the citadel, but both were forced to submit as a protectorate, and pay tribute to, the Qing dynasty in China between 1774 and 1798.

Narbuta Beg’s son Alim was both ruthless and efficient. He hired a mercenary army of Tajik highlanders, and conquered the western half of the Fergana Valley, including Khujand and Tashkent. He was assassinated by his brother Omar in 1809. Omar’s son, Mohammed Ali (Madali Khan), ascended to the throne in 1821 at the age of 12. During his reign, the Khanate of Kokand reached its greatest territorial extent. The Kokand Khanate also housed the Khojas of Kashgar like Jahangir Khoja. In 1841, the British officer Captain Arthur Conolly failed to persuade the various khanates to put aside their differences, in an attempt to counter the growing penetration of the Russian Empire into the area. In November 1841, he left Kokand for Bukhara in an ill-fated attempt to rescue fellow officer Colonel Charles Stoddart, and both were executed on June 24, 1842 by the order of Emir Nasrullah Khan of Bukhara.[3]

Following this, Madali Khan, who had received Conolly in Kokand, and who had also sought an alliance with Russia, lost the trust of Nasrullah. The Emir, encouraged by the conspiratorial efforts of several influential figures in Kokand (including the commander in chief of its army), invaded the khanate in 1842. Shortly thereafter he executed Madali Khan, his brother, and Omar Khan's widow, the famed poetess Nadira. Madali Khan’s cousin, Shir Ali, was installed as the Khan of Kokand in June 1842.[4] Over the next two decades, the khanate was weakened by a bitter civil war, which was further exacerbated by Bukharan and Russian incursions. Shir Ali’s son, Khudayar Khan, ruled from 1845 to 1858, and, following another interlude under Emir Nasrullah, again from 1865. In the meantime, Russia was continuing its advance: on June 28, 1865 Tashkent was taken by the Russian troops of General Chernyayev; the loss of Khujand followed in 1867.

Shortly before the fall of Tashkent, Kokand’s best known son, Yakub Beg, former lord of Tashkent, was sent by the then Khan of Kokand, Alimqul, to Kashgar, where the Hui Muslims were in revolt against the Chinese. When Alimqul was killed in 1867 following the loss of Tashkent, many Kokandian soldiers fled to join Yaqub Beg, helping him establish his dominion throughout the Tarim Basin, which lasted until 1877, when Qing reconquered the region.

In 1868, a treaty turned Kokand into a Russian vassal state. The now powerless Khudayar Khan spent his energies improving his lavish palace. Western visitors were impressed by the city of 80,000 people, which contained some 600 mosques and 15 madrasahs. Insurrections against Russian rule and Khudayar’s oppressive taxes forced him into exile in 1875. He was succeeded by his son, Nasir ad-din Abdul Karim Khan, whose anti-Russian stance provoked the annexation of Kokand (after six months of fierce fighting) by Generals Konstantin von Kaufman and Mikhail Skobelev. In March 1876, Tsar Alexander II stated that he had been forced to "... yield to the wishes of the Kokandi people to become Russian subjects." The Khanate of Kokand was declared abolished, and incorporated into the Fergana Province of Russian Turkestan. Nasir ad-din Abdul Karim Khan fled to India through the Pamirs and Afghanistan. He died in 1893 in the city of Peshawar, Pakistan (Then British India). His family is now inhabitant in Mir Tayyab Ghari, Peshawar.

Altun Bishik

The Khans of Kokand had a connection with the Timurid Empire (1370–1507). From the time of the last Timurids to that of the first Khans of Kokand there was a period of more than two hundred years. The Khans' genealogy was connected with Babur through a legendary figure, Altun Bishik. In the legend, a baby of Babur's family was left in a bishik (cradle) when Babur fled prosecution, fleeing to the limits of Transoxiana. The child was named Altun Bishik, after its imperial cradle, and in the legend he lived from 918-952 AH / 1512-1545 AD. Bishik may have been an historic figure, as he has appeared in historical sources. In the legend, this baby is the ancestor of the Khans of Kokand, making appearances in manuscripts on Kokand history since the beginning of the 19th century.

Khans of Kokand (1709-1876)

- Shahrukh Bı (1709–1721)

- Abdu’l Rahım Bı (1721–1733)

- Abdu’l Kahım Bı (1733–1746)

- Irdana (1751–1770)

- Narbuta Beg (1774–1798)

- Alim Khan (1798–1810)

- Muhammad Umar Khan (1810–1822) (styled Amir al-Muslimin from 1814)

- Muhammad Ali Khan (1822–1842)

- Shir Ali Khan (June 1842 - 1845)

- Murad Beg Khan (1845)

- Muhammad Khudayar Khan (1845–1852) (1st time)

- Muhammad Khudayar Khan (1853–1858) (2nd time)

- Muhammad Mallya Beg Khan (1858 - 1 March 1862)

- Shah Murad Khan (1862)

- Muhammad Khudayar Khan (1862–1865) (3rd time)

- Muhammad Sultan Khan (1863 - March 1865) (1st time) (with Alimqul as the regent)

- Bil Bahchi Khan (1865)

- Muhammad Sultah Khan (1865–1866) (2nd time)

- Muhammad Khudayar Khan (1866 - 22 July 1875) (4th time)

- Nasir ad-Din Khan (1875) (1st time)

- Muhammad Pulad Beg Khan (1875 - December 1875)

- Nasir ad-Din Abdul Karim Khan (December 1875 - 19 February 1876) (2nd time)

See also

References

References

- "The Muslim World"; Part III, "The Last Great Muslim Empires": Translation and Adaptations by F.R.C. Bagley. (Originally published 1969). Brill Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-90-04-02104-4.

- Beisembiev T. K. Kokandskaia istoriografiia : Issledovanie po istochnikovedeniiu Srednei Azii XVIII-XIX vekov. Almaty, TOO "PrintS", 2009, 1263 pp., ISBN 978-9965-482-84-7.

- Beisembiev T. "Annotated indices to the Kokand Chronicles". Tokyo: Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. Studia Culturae Islamica. № 91, 2008, 889 pp., ISBN 978-4-86337-001-2.

- Beisembiev T. "The Life of Alimqul: A Native Chronicle of Nineteenth Century Central Asia". Published 2003. Routledge (UK), 280 pages, ISBN 978-0-7007-1114-7.

- Beisembiev T.K. "Ta'rikh-i SHakhrukhi" kak istoricheskii istochnik. Alma Ata: Nauka, 1987. 200 p. Summaries in English and French.

- Beisembiev T.K. "Legenda o proiskhozhdenii kokandskikh khanov kak istochnik po istorii ideologii v Srednei Azii (na materialakh sochinenii kokandskoi istoriografii)". Kazakhstan, Srednjaja i Tsentralnaia Azia v XVI-XVIII vv. Alma-ata, 1983, pp. 94–105

- Dubavitski, Victor and Bababekov, Khaydarbek, in S. Frederick Starr, ed., Ferghana Valley: The Heart of Central Asia, pp. 31–33.

- Howorth, Sir Henry Hoyle. History of the Mongols: From the 9th to the 19th Century, Volume 2, Issue 2, pp. 795–801,816-845.

- Nalivkine V. P. Histoire du Khanat de Khokand. Trad. A.Dozon. Paris, 1889.

- Nalivkin V. "Kratkaia istoria kokandskogo khanstvа". Istoria Srednei Azii. A.I.Buldakov, S.A.Shumov, A.R.Andreev (eds.). Moskva, 2003, pp. 288–290.

- Vakhidov Sh.Kh. ХIХ-ХХ asr bāshlarida Qoqān khānligida tarikhnavislikning rivājlanishi. Tarikh fanlari doktori dissertatsiyasi. Tāshkent, 1998, pp. 114–137.

- Aftandil S.Erkinov. "Imitation of Timurids and Pseudo-Legitimation: On the origins of a manuscript anthology of poems dedicated to the Kokand ruler Muhammad Ali Khan (1822–1842)". <http://wcms-neu1.urz.uni-halle.de/download.php?down=9046&elem=1986852> GSAA Online Working Paper No. 5 [1]

- Aftandil S.Erkinov. "Les timourides, modeles de legitimite et les recueils poetiques de Kokand". Ecrit et culture en Asie centrale et dans le monde Turko-iranien, XIVe-XIXe siècles // Writing and Culture in Central Asia and in the Turko-Iranian World, 14th-19th Centuries. F.Richard, M.Szuppe (eds.), [Cahiers de Studia Iranica. 40]. Paris: AAEI, 2009, pp. 285–330.

- Scott Levi. "Babur’s Legacy and Political Legitimacy in the Khanate of Khoqand." to be submitted to the Journal of Asian Studies.

External links

Coordinates: 40°31′43″N 70°56′33″E / 40.5286°N 70.9425°E

|