Kepler problem

In classical mechanics, the Kepler problem is a special case of the two-body problem, in which the two bodies interact by a central force F that varies in strength as the inverse square of the distance r between them. The force may be either attractive or repulsive. The "problem" to be solved is to find the position or speed of the two bodies over time given their masses and initial positions and velocities. Using classical mechanics, the solution can be expressed as a Kepler orbit using six orbital elements.

The Kepler problem is named after Johannes Kepler, who proposed Kepler's laws of planetary motion (which are part of classical mechanics and solve the problem for the orbits of the planets) and investigated the types of forces that would result in orbits obeying those laws (called Kepler's inverse problem).[1]

For a discussion of the Kepler problem specific to radial orbits, see: Radial trajectory. The Kepler problem in general relativity produces more accurate predictions, especially in strong gravitational fields.

Applications

The Kepler problem arises in many contexts, some beyond the physics studied by Kepler himself. The Kepler problem is important in celestial mechanics, since Newtonian gravity obeys an inverse square law. Examples include a satellite moving about a planet, a planet about its sun, or two binary stars about each other. The Kepler problem is also important in the motion of two charged particles, since Coulomb’s law of electrostatics also obeys an inverse square law. Examples include the hydrogen atom, positronium and muonium, which have all played important roles as model systems for testing physical theories and measuring constants of nature.

The Kepler problem and the simple harmonic oscillator problem are the two most fundamental problems in classical mechanics. They are the only two problems that have closed orbits for every possible set of initial conditions, i.e., return to their starting point with the same velocity (Bertrand's theorem). The Kepler problem has often been used to develop new methods in classical mechanics, such as Lagrangian mechanics, Hamiltonian mechanics, the Hamilton–Jacobi equation, and action-angle coordinates. The Kepler problem also conserves the Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector, which has since been generalized to include other interactions. The solution of the Kepler problem allowed scientists to show that planetary motion could be explained entirely by classical mechanics and Newton’s law of gravity; the scientific explanation of planetary motion played an important role in ushering in the Enlightenment.

Mathematical definition

The central force F that varies in strength as the inverse square of the distance r between them:

where k is a constant and  represents the unit vector along the line between them.[2] The force may be either attractive (k<0) or repulsive (k>0). The corresponding scalar potential (the potential energy of the non-central body) is:

represents the unit vector along the line between them.[2] The force may be either attractive (k<0) or repulsive (k>0). The corresponding scalar potential (the potential energy of the non-central body) is:

Solution of the Kepler problem

The equation of motion for the radius  of a particle

of mass

of a particle

of mass  moving in a central potential

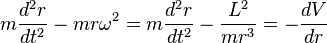

moving in a central potential  is given by Lagrange's equations

is given by Lagrange's equations

and the angular momentum

and the angular momentum  is conserved. For illustration, the first term on the left-hand side is zero for circular orbits, and the applied inwards force

is conserved. For illustration, the first term on the left-hand side is zero for circular orbits, and the applied inwards force  equals the centripetal force requirement

equals the centripetal force requirement  , as expected.

, as expected.

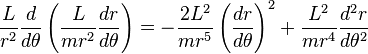

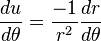

If L is not zero the definition of angular momentum allows a change of independent variable from  to

to

giving the new equation of motion that is independent of time

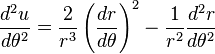

The expansion of the first term is

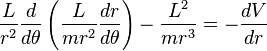

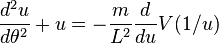

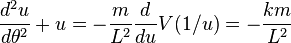

This equation becomes quasilinear on making the change of variables  and multiplying both sides by

and multiplying both sides by

After substitution and rearrangement:

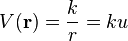

For an inverse-square force law such as the gravitational or electrostatic potential, the potential can be written

The orbit  can be derived from the general equation

can be derived from the general equation

whose solution is the constant  plus a simple sinusoid

plus a simple sinusoid

where  (the eccentricity) and

(the eccentricity) and  (the phase offset) are constants of integration.

(the phase offset) are constants of integration.

This is the general formula for a conic section that has one focus at the origin;  corresponds to a circle,

corresponds to a circle,  corresponds to an ellipse,

corresponds to an ellipse,  corresponds to a parabola, and

corresponds to a parabola, and  corresponds to a hyperbola. The eccentricity

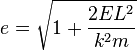

corresponds to a hyperbola. The eccentricity  is related to the total energy

is related to the total energy  (cf. the Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector)

(cf. the Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector)

Comparing these formulae shows that  corresponds to an ellipse (all solutions which are closed orbits are ellipses),

corresponds to an ellipse (all solutions which are closed orbits are ellipses),  corresponds to a parabola, and

corresponds to a parabola, and  corresponds to a hyperbola. In particular,

corresponds to a hyperbola. In particular,  for perfectly circular orbits (the central force exactly equals the centripetal force requirement, which determines the required angular velocity for a given circular radius).

for perfectly circular orbits (the central force exactly equals the centripetal force requirement, which determines the required angular velocity for a given circular radius).

For a repulsive force (k > 0) only e > 1 applies.

See also

- Action-angle coordinates

- Bertrand's theorem

- Binet equation

- Hamilton–Jacobi equation

- Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector

- Kepler orbit

- Kepler problem in general relativity

- Kepler's equation

- Kepler's laws of planetary motion

References

- ↑ Goldstein, H. (1980). Classical Mechanics (2nd ed.). Addison Wesley.

- ↑ Arnold, VI (1989). Mathematical Methods of Classical Mechanics, 2nd ed. New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 38. ISBN 0-387-96890-3.

![u \equiv \frac{1}{r} = -\frac{km}{L^{2}} \left[ 1 + e \cos \left( \theta - \theta_{0}\right) \right]](../I/m/e6dbb49a0a921664aefc4168bf77c262.png)