Kelvin–Voigt material

A Kelvin–Voigt material, also called a Voigt material, is a viscoelastic material having the properties both of elasticity and viscosity. It is named after the British physicist and engineer Lord Kelvin and after German physicist Woldemar Voigt.

Definition

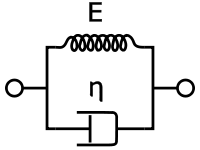

The Kelvin–Voigt model, also called the Voigt model, can be represented by a purely viscous damper and purely elastic spring connected in parallel as shown in the picture.

If we connect these two elements in series we get a model of a Maxwell material.

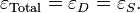

Since the two components of the model are arranged in parallel, the strains in each component are identical:

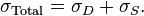

Similarly, the total stress will be the sum of the stress in each component:

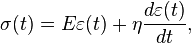

From these equations we get that in a Kelvin–Voigt material, stress σ, strain ε and their rates of change with respect to time t are governed by equations of the form:

where E is a modulus of elasticity and  is the viscosity. The equation can be applied either to the shear stress or normal stress of a material.

is the viscosity. The equation can be applied either to the shear stress or normal stress of a material.

Effect of a sudden stress

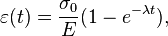

If we suddenly apply some constant stress  to Kelvin–Voigt material, then the deformations would approach the deformation for the pure elastic material

to Kelvin–Voigt material, then the deformations would approach the deformation for the pure elastic material  with the difference decaying exponentially:

with the difference decaying exponentially:

where t is time and  the rate of relaxation

the rate of relaxation  .

.

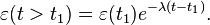

If we would free the material at time  , then the elastic element would retard the material back until the deformation becomes zero. The retardation obeys the following equation:

, then the elastic element would retard the material back until the deformation becomes zero. The retardation obeys the following equation:

The picture shows the dependence of the dimensionless deformation  on dimensionless time

on dimensionless time  . In the picture the stress on the material is loaded at time

. In the picture the stress on the material is loaded at time  , and released at the later dimensionless time

, and released at the later dimensionless time  .

.

Since all the deformation is reversible (though not suddenly) the Kelvin–Voigt material is a solid.

The Voigt model predicts creep more realistically than the Maxwell model, because in the infinite time limit the strain approaches a constant:

while a Maxwell model predicts a linear relationship between strain and time, which is most often not the case. Although the Kelvin–Voigt model is effective for predicting creep, it is not good at describing the relaxation behavior after the stress load is removed.

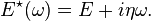

Dynamic modulus

The complex dynamic modulus of the Kelvin–Voigt material is given by:

Thus, the real and imaginary components of the dynamic modulus are:

Note that  is constant, while

is constant, while  is directly proportional to frequency (where the apparent viscosity,

is directly proportional to frequency (where the apparent viscosity,  , is the constant of proportionality).

, is the constant of proportionality).

References

- Meyers and Chawla (1999): Section 13.10 of Mechanical Behaviors of Materials, Mechanical behavior of Materials, 570–580. Prentice Hall, Inc.

- http://stellar.mit.edu/S/course/3/fa06/3.032/index.html

![E_1 = \Re [E( \omega )] = E,](../I/m/00aa8c366cf6852a38d110e31ea3b49e.png)

![E_2 = \Im [E( \omega )] = \eta \omega.](../I/m/373bd7510a17db65b6e01ed3f9f25f3b.png)