Karl Georg Christian von Staudt

| Karl G. C. von Staudt | |

|---|---|

|

Karl von Staudt (1798 - 1867) | |

| Born |

24 January 1798 Free Imperial City of Rothenburg (modern day Rothenburg ob der Tauber, Germany) |

| Died |

1 June 1867 Erlangen |

| Residence | Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Fields |

Astronomy Mathematics |

| Alma mater | University of Erlangen |

| Doctoral advisor | Gauss |

| Known for |

Algebra of throws von Staudt-Clausen theorem |

| Influences | Gauss |

| Influenced |

Eduardo Torroja Caballe Corrado Segre Mario Pieri |

Karl Georg Christian von Staudt (January 24, 1798 – June 1, 1867) was a German mathematician who used synthetic geometry to provide a foundation for arithmetic.

Life and influence

Karl was born in the Free Imperial City of Rothenburg, which is now called Rothenburg ob der Tauber in Germany. From 1814 he studied in Gymnasium in Ausbach. He attended the University of Göttingen from 1818 to 1822 where he studied with Gauss who was director of the observatory. Staudt provided an ephemeris for the orbits of Mars and the asteroid Pallas. When in 1821 Comet Nicollet-Pons was observed, he provided the elements of its orbit. These accomplishments in astronomy earned him his doctorate from University of Erlangen in 1822.

Staudt's professional career began as a secondary school instructor in Würzburg until 1827 and then Nuremberg until 1835. He married Jeanette Dreschler in 1832. They had a son Eduard and daughter Mathilda, but Jeanette died in 1848.

The book Geometrie der Lage (1847) was a landmark in projective geometry. As Burau (1976) wrote:

- Staudt was the first to adopt a fully rigorous approach. Without exception his predecessors still spoke of distances, perpendiculars, angles and other entities that play no role in projective geometry.[1]

Furthermore, this book (page 43) uses the complete quadrangle to "construct the fourth harmonic associated with three points on a straight line", the projective harmonic conjugate.

Indeed, in 1889 Mario Pieri translated von Staudt, before writing his I Principii della Geometrie di Posizione Composti in un Systema Logico-deduttivo (1898). In 1900 Charlotte Scott of Bryn Mawr College paraphased much of von Staudt's work in English for The Mathematical Gazette.[2] When Wilhelm Blaschke published his textbook Projective Geometry in 1948, a portrait of the young Karl was placed opposite the Vorwort.

Staudt went beyond real projective geometry and into complex projective space in his three volumes of Beiträge zur Geometrie der Lage published from 1856 to 1860.

In 1922 H. F. Baker wrote of von Staudt's work:

- It was von Staudt to whom the elimination of the ideas of distance and congruence was a conscious aim, if, also, the recognition of the importance of this might have been much delayed save for the work of Cayley and Klein upon the projective theory of distance. Generalised, and combined with the subsequent Dissertation of Riemann, v. Staudt's volumes must be held to be the foundation of what, on its geometrical side, the Theory of Relativity, in Physics, may yet become.[3]

Von Staudt is also remembered for his view of conic sections and the relation of pole and polar:

- Von Staudt made the important discovery that the relation which a conic establishes between poles and polars is really more fundamental than the conic itself, and can be set up independently. This "polarity" can then be used to define the conic, in a manner that is perfectly symmetrical and immediately self-dual: a conic is simply the locus of points which lie on their polars, or the envelope of lines which pass through their poles. Von Staudt’s treatment of quadrics is analogous, in three dimensions.[4]

Algebra of throws

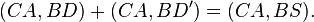

In 1857, in the second Beiträge, von Staudt contributed a route to number through geometry called the algebra of throws (German: Wurftheorie). It is based on projective range and the relation of projective harmonic conjugates. Through operations of addition of points and multiplication of points, one obtains an "algebra of points", as in chapter 6 of Veblen & Young's textbook on projective geometry. The usual presentation relies on cross ratio (CA,BD) of four collinear points. For instance, Coolidge wrote:[5]

- How do we add two distances together? We give them the same starting point, find the point midway between their terminal points, that is to say, the harmonic conjugate of infinity with regard to their terminal points, and then find the harmonic conjugate of the initial point with regard to this mid-point and infinity. Generalizing this, if we wish to add throws (CA,BD) and (CA,BD' ), we find M the harmonic conjugate of C with regard to D and D' , and then S the harmonic conjugate of A with regard to C and M :

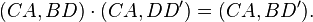

- In the same way we may find a definition of the product of two throws. As the product of two numbers bears the same ratio to one of them as the other bears to unity, the ratio of two numbers is the cross ratio which they as a pair bear to infinity and zero, so Von Staudt, in the previous notation, defines the product of two throws by

- These definitions involve a long series of steps to show that the algebra so defined obeys the usual commutative, associative, and distributive laws, and that there are no divisors of zero.

A summary statement is given by Veblen & Young[6] as Theorem 10: "The set of points on a line, with  removed, forms a field with respect to the operations previously defined". As Freudenthal notes[7]:199

removed, forms a field with respect to the operations previously defined". As Freudenthal notes[7]:199

- ...up to Hilbert, there is no other example for such a direct derivation of the algebraic laws from geometric axioms as found in von Staudt's Beiträge.

Another affirmation of von Staudt's work with the harmonic conjugates comes in the form of a theorem:

- The only one-to-one correspondence between the real points on a line which preserves the harmonic relation between four points is a non-singular projectivity.[8]

The algebra of throws was described as "projective arithmetic" in The Four Pillars of Geometry (2005).[9] In a section called "Projective arithmetic", he says

- The real difficulty is that the construction of a + b , for example, is different from the construction of b + a, so it is a "coincidence" if a + b = b + a. Similarly it is a "coincidence" if ab = ba, of any other law of algebra holds. Fortunately, we can show that the required coincidences actually occur, because they are implied by certain geometric coincidences, namely the Pappus and Desargues theorems.

If one interprets von Staudt’s work as a construction of the real numbers, then it is incomplete. One of the required properties is that a bounded sequence has a cluster point. As Hans Freudenthal observed:

- To be able to consider von Staudt's approach as a rigorous foundation of projective geometry, one need only add explicitly the topological axioms which are tacitly used by von Staudt. ... how can one formulate the topology of projective space without the support of a metric? Von Staudt was still far from raising this question, which a quarter of a century later would become urgent. ... Felix Klein noticed the gap in von Staudt's approach; he was aware of the need to formulate the topology of projective space independently of Euclidean space.... the Italians were the first to find truly satisfactory solutions for the problem of a purely projective foundation of projective geometry, which von Staudt had tried to solve.[7]

One of the Italian mathematicians was Giovanni Vailati who studied the circular order property of the real projective line. The science of this order requires a quaternary relation called the separation relation. Using this relation, the concepts of monotone sequence and limit can be addressed, in a cyclic "line". Assuming that every monotone sequence has a limit,[10] the line becomes a complete space. These developments were inspired by von Staudt’s deductions of field axioms as an initiative in the derivation of properties of ℝ from axioms in projective geometry.

Works

- 1831: Über die Kurven, 2. Ordnung. Nürnberg

- 1845: De numeris Bernoullianis: commentationem alteram pro loco in facultate philosophica rite obtinendo, Carol. G. Chr. de Staudt. Erlangae: Junge.

- 1845: De numeris Bernoullianis: loci in senatu academico rite obtinendi causa commentatus est, Carol. G. Chr. de Staudt. Erlangae: Junge.

The following links are to Cornell University Historical Mathematical Monographs:

- 1847: Geometrie der Lage. Nürnberg.

- 1856: Beiträge zur Geometrie der Lage, Erstes Heft. Nürnberg.

- 1857: Beiträge zur Geometrie der Lage, Zweites Heft. Nürnberg.

- 1860: Beiträge zur Geometrie der Lage, Drittes Heft. Nürnberg.

See also

References

- ↑ Walter Burau (1976) "Karl Georg Christian von Staudt", Dictionary of Scientific Biography, auspices of American Council of Learned Societies

- ↑ Charlotte Scott (1900) "On von Staudt's Geometrie der Lage", The Mathematical Gazette 1(19):307–14, 1(20):323–31, 1(22):363–70

- ↑ H. F. Baker (1922) Principles of Geometry, volume 1, page176, Cambridge University Press

- ↑ H.S.M. Coxeter (1942) Non-Euclidean Geometry, pp 48,9, University of Toronto Press

- ↑ J. L. Coolidge (1940) A History of Geometrical Methods, pages 100, 101, Oxford University Press

- ↑ Veblen & Young page 141

- 1 2 Hans Freudenthal (1974) "The Impact of Von Staudt's Foundations of Geometry", in For Dirk Struik, R.S. Cohen editor, D. Reidel. Also found in Geometry – von Staudt’s Point of View, Peter Plaumann & Karl Strambach editors, Proceedings of NATO Advanced Study Institute, Bad Windsheim, July/August 1980, D. Reidel, ISBN 90-277-1283-2

- ↑ Dirk Struik (1953) Lectures on Analytic and Projective Geometry, p 22, "theorem of von Staudt"

- ↑ John Stillwell, Sheldon Axler, Ken A. Ribet (2005) The Four Pillars of Geometry, page 128, Springer: Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics ISBN 978-0-387-29052-2

- ↑ H. S. M. Coxeter (1949) The Real Projective Plane, Chapter 10: Continuity, McGraw Hill

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Karl George Christian von Staudt", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- Veblen, Oswald; Young, J. W. A. (1938). Projective geometry. Boston: Ginn & Co. ISBN 978-1-4181-8285-4.

- John Wesley Young (1930) Projective Geometry, Chapter 8: Algebra of points and the introduction of analytic methods, Open Court for Mathematical Association of America.

|