Kallikantzaros

| Grouping | Folklore |

|---|---|

| Sub grouping | Goblin |

| Other name(s) | karakoncolos, karakondžula, karakondzhol |

| Country | Greece, Bulgaria, Macedonia, Serbia, Turkey, Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| Region | Southeastern Europe |

The kallikantzaros (Greek: Καλλικάντζαρος; Bulgarian: караконджул; pl. kallikantzaroi) is a malevolent goblin in Southeastern European and Anatolian folklore. Stories about the kallikantzaros or its equivalents can be found in Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia, Bosnia and Turkey. Kallikantzaroi are believed to dwell underground but come to the surface during the twelve days of Christmas, from 25 December to 6 January (from the winter solstice for a fortnight during which time the sun ceases its seasonal movement).

Etymology

Amongst other proposed etymologies, the term kallikantzaros is speculated to be derived from the Greek kalos-kentauros ("beautiful centaur"), although this theory has met with considerable opposition.[1]

In Greek folklore

It is believed that kallikantzaroi stay underground sawing the world tree, so that it will collapse, along with Earth.[1] However, according to folklore, when they are about to saw the final part, Christmas dawns and they are able to come to the surface. They forget the tree and come to bring trouble to mortals.

Finally, on the Epiphany (6 January), the sun starts moving again, and they must go underground again to continue their sawing. They see that during their absence the world tree has healed itself, so they must start working all over again. This is believed to occur annually.

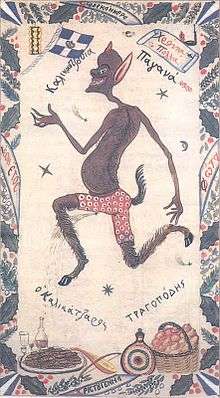

Appearance

There is no standard description of the appearance of kallikantzaroi; there are regional variations in how their appearance is described. Some Greeks have imagined them with some animal parts, like hairy bodies, horse legs, or boar tusks; sometimes enormous, other times diminutive. Others see them as humans of small size that smell horrible. They are predominantly male, often with protruding sex characteristics.[1] Many Greeks have imagined them as tall, black, hairy, with burning red eyes, goats' or donkeys' ears, monkeys' arms, tongues that hang and heads that are huge.[2] Nonetheless, the most common belief is that they are small, black creatures, humanoid apart from their long black tails. The shape of the kallikantzaros is said to resemble that of a little, black devil. They are, also, mostly blind, speak with a lisp and love to eat frogs, worms, and other small creatures.[3]

Lore

Kallikantzaroi are believed to be creatures of the night. According to folklore, there were many ways people could protect themselves during the days when the kallikantzaroi were loose. One such method was to leave a colander on their doorstep to trick the visiting kallikantzaros. It was believed that since it could not count above two – three was believed to be a holy number, and by pronouncing it, the kallikantzaros would supposedly kill itself – the kallikantzaros would sit at the doorstep all night, counting each hole of the colander, until the sun rose and it was forced to hide.

Another supposed method of protection from kallikantzaroi was to leave the fire burning in the fireplace, all night, so that they could not enter through it. In some areas, people would burn the Yule log for the duration of the twelve days. In other areas, people would throw foul-smelling shoes in the fire, as the stench was believed to repulse the kallikantzaroi and thus force them to stay away. Additional ways to keep them away included marking one's door with a black cross on Christmas Eve and burning incense.[4]

According to legend, any child born during the twelve days of Christmas was in danger of transforming to a kallikantzaros during each Christmas season, starting with adulthood. It was believed that the antidote to prevent this transformation was to bind the baby in tresses of garlic or straw, or to singe the child's toenails. According to another legend, anyone born on a Saturday could see and talk with the kallikantzaroi.[5]

One particularity that set the kallikantzaroi apart from other goblins or creatures in folklore was that they were said to appear on Earth for only twelve days each year. Their short duration on earth, as well as the fact that they were not considered purely malevolent creatures but rather impish and stupid, led to a number of theories about their creation. One such theory connects them to the masquerades of the ancient Roman winter festival of Bacchanalia, and later the Greek Dionysia. During the drunken, orgiastic parts of the festivals, people wearing masks, hidden under costumes in bestial shapes yet still appearing humanoid, may have made an exceptional impression on the minds of simple folk who were intoxicated.[4]

In Greek, the term kallikantzaros is also used to describe a number of other short, ugly and usually mischievous beings in folklore. When not used for the abovementioned creatures, it seems to express the collective sense for the Irish word leprechaun and the English words gnome and goblin.

In Serbian folklore

In Serbian Christmas traditions, the Twelve Days of Christmas were previously called the "unbaptized days" and were considered a time when demonic forces of all kinds were believed to be more active and dangerous than usual. People were cautious not to attract their attention, and did not go out late at night. The latter precaution was especially because of the mythical demons called karakondžula (Serbian Cyrillic: Караконџула; also karakondža, karakandža or karapandža), imagined as heavy, squat, and ugly creatures. According to tradition, when a karakondžula found someone outdoors during the night of an unbaptized day, it would jump on the person's back and demand to be carried wherever it wanted. This torture would end only when roosters announced the dawn; at that moment the creature would release its victim and run away.[6]

In Anatolian folklore

The karankoncolos is a malevolent creature in Northeast Anatolian Turkish folklore. It is a variety of bogeyman, usually merely troublesome and rather harmless, but sometimes truly evil. It is believed to have thick hairy fur like the Sasquatch. The Turkish name is derived from the Greek name. According to late Ottoman Turkish myth, they appear on the first ten days of Zemheri ("the dreadful cold") when they stand on murky corners, and ask seemingly ordinary questions to passers-by. The legend states that in order to escape harm, one should answer each question, using the word kara (Turkish for "black"), or risk being struck dead by the creature. It was also said in Turkish folklore that the karakoncolos could call people out during the cold Zemheri nights by imitating voices of loved ones. The victim of the karakoncolos risked freezing to death if he or she could not awake from the charm.

In Bulgarian folklore

The Bulgarian name of the creature is karakondjul (or karakondjol, Bulgarian: караконджол). The Karakondjul walks at night. A Bulgarian custom called kukeri (or koukeri) is performed to scare away the evil creature and avoid contact with it.

In popular culture

Kallikantzaroi are the subject of the Grimm episode "The Grimm Who Stole Christmas".

The narrator/protagonist of Roger Zelazny's novel This Immortal is a Greek born on Christmas Day. The book's first sentence is his new wife teasingly calling him a "kallikanzaros" [sic], although she doesn't mean anything hostile by it. The reference comes up several other times throughout the story.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Carlo Ginzburg (14 June 2004). Ecstasies: Deciphering the Witches' Sabbath. University of Chicago Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-226-29693-7.

According to one etymological conjecture that has met with many objections, the term kallikantzaros derives from kalos-kentauros (beautiful centaur).

- ↑ Miles, Clement A. (2008). Christmas in Ritual and Tradition, Christian and Pagan. USA: Zhingoora Books. p. 244. ISBN 978-1434473769.

- ↑ Μανδηλαρἀς, Φἰλιππος (2005). Ιστοριες με Καλικἀντζαρους (in Greek). Εκδὀσεις Πατἀκης. p. 11. ISBN 960-16-1742-6. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- 1 2 Miles 2008, p. 245.

- ↑ Μανδηλαρἀς 2005, p. 20.

- ↑ Vuković, Milan T. (2004). "Божићни празници". Народни обичаји, веровања и пословице код Срба [Serbian folk customs, beliefs, and sayings] (in Serbian) (12 ed.). Belgrade: Sazvežđa. p. 94. ISBN 86-83699-08-0.

Sources

- Özhan Öztürk. (Black Sea: Encyclopedic Dictionary) Karadeniz Ansiklopedik Sözlük. 2 Vol. Heyamola Publishing. Istanbul. 2005 ISBN 975-6121-00-9