Kaiserreich abdication of Wilhelm II

| Abdication statement of Emperor Wilhelm II | |

|---|---|

| |

| 28 November 1918 |

The Kaiserreich[1] abdication was issued by Wilhelm II, German Emperor, the last German Emperor (Kaiser) and King of Prussia. He ruled the German Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia from 15 June 1888 to 9 November 1918. Kaiser Wilhelm II issued his abdication statement on 28 November 1918, from exile in Amerongen. Following the abdication statement and German Revolution of 1918–19, the German nobility as a legally defined class was abolished. On promulgation of the Weimar Constitution on 11 August 1919, all Germans were declared equal before the law.[2] Altogether abolished were titles borne exclusively by monarchs; eg, emperor/empress, king/queen, grand duke/grand duchess, etc. There were 22 federal princes of the Kaiserreich (within Germany), who lost their titles and domains. Of these princely heads of state, 4 held the title King (König) (the Kings of Prussia, Bavaria, Saxony, and Württemberg), 6 held the title Grand Duke (Großherzog), 5 held the title Duke (Herzog), and 7 held the title Prince (i.e. Sovereign Prince, Fürst).

"Statement of Abdication"

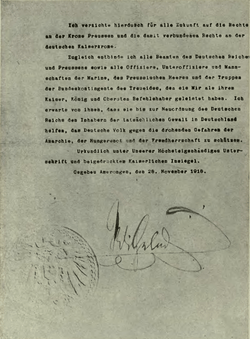

Wilhelm first settled in Amerongen, where on 28 November he issued a belated statement of abdication from both the Prussian and imperial thrones, thus formally ending the House of Hohenzollern's 400-year rule over Prussia. Accepting the reality that he had lost both of his crowns for good, he gave up his rights to "the throne of Prussia and to the German Imperial throne connected therewith." He also released his soldiers and officials in both Prussia and the empire from their oath of loyalty to him.[3]

- Statement of Abdication. I herewith renounce for all time claims to the throne of Prussia and to the German Imperial throne connected therewith. At the same time I release all officials of the German Empire and of Prussia, as well as all officers, non-commissioned officers and men of the navy and of the Prussian army, as well as the troops of the federated states of Germany, from the oath of fidelity which they tendered to me as their Emperor, King and Commander-in-Chief. I expect of them that until the re-establishment of order in the German Empire they shall render assistance to those in actual power in Germany, in protecting the German people from the threatening dangers of anarchy, famine, and foreign rule. Proclaimed under our own hand and with the imperial seal attached. Amerongen, 28 November 1918. Signed WILLIAM.[4]

Abdication negotiations

After the Oberste Heeresleitung stated the German front was about to collapse and asked for immediate negotiation of an armistice, the cabinet of Chancellor Georg von Hertling resigned on 30 September 1918. Hertling, with the support of Haußmann, Oberst Hans von Haeften and Erich Ludendorff suggested Prince Max as his successor. To have Wilhelm II appoint Max as Chancellor of Germany and Minister President of Prussia.[5][6] When Max arrived in Berlin on 1 October, Emperor Wilhelm II convinced him to take the post and appointed him on 3 October 1918. The message asking for an armistice went out on 4 October, hopefully to be accepted by President of the United States Woodrow Wilson.[7]:44 In late October, Wilson's third note seemed to imply that negotiations of an armistice would be dependent on the abdication of Wilhelm II. On 1 November, Max wrote to all the ruling Princes of Germany, asking them whether they would approve of an abdication by the Emperor.[6] On 6 November, Maximilian urged Wilhelm II to abdicate. The Kaiser, who had fled from Berlin to the Spa, Belgium OHL-headquarters, was willing to consider abdication only as Emperor, not as King of Prussia.

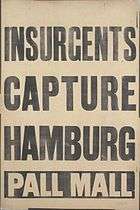

Around 4 November delegations of sailors dispersed to all of the country's big cities. By 7 November the revolution had seized all large coastal cities as well as Hanover, Brunswick, Frankfurt on Main and Munich. On 7 November, Max met with Friedrich Ebert, leader of the Social Democratic Party of Germany and discussed his plan to go to Spa and convince Wilhelm II to abdicate. He was thinking about setting up Wilhelm's second son as regent.[7]:76 However, the outbreak of the revolution in Berlin prevented Max from implementing his plan. Ebert decided that to keep control of the socialist uprising the Emperor had to resign quickly and that a new government was required.[7]:77 As the masses gathered in Berlin, at noon on 9 November 1918, Maximilian went ahead and unilaterally announced the abdication, as well as the renunciation of Crown Prince Wilhelm.[7]:86

Abdication and flight

After the outbreak of the German Revolution, Wilhelm could not make up his mind whether or not to abdicate. Up to that point, he accepted that he would likely have to give up the imperial crown, but still hoped to retain the Prussian kingship. However, this was impossible under the Constitution of the German Empire. While Wilhelm thought he ruled as emperor in a personal union with Prussia, the constitution actually tied the imperial crown to the Prussian crown, meaning that Wilhelm could not renounce one crown without renouncing the other. Wilhelm's hopes of retaining at least one of his crowns was revealed as unrealistic when, in the hope of preserving the monarchy in the face of growing revolutionary unrest, Chancellor Prince Max of Baden announced Wilhelm's abdication of both titles on 9 November 1918. Prince Max himself was forced to resign later the same day, when it became clear that only Friedrich Ebert, leader of the SPD, could effectively exert control. Later that day, one of Ebert's secretaries of state (ministers), Social Democrat Philipp Scheidemann, proclaimed Germany a republic. Wilhelm consented to the abdication only after Ludendorff's replacement, General Wilhelm Groener, had informed him that the officers and men of the army would march back in good order under Paul von Hindenburg's command, but would certainly not fight for Wilhelm's throne on the home front. The monarchy's last and strongest support had been broken, and finally even Hindenburg, himself a lifelong royalist, was obliged, with some embarrassment, to advise the Emperor to give up the crown.[8]

On 10 November, Wilhelm crossed the border by train and went into exile in the Netherlands, which had remained neutral throughout the war.[9] Upon the conclusion of the Treaty of Versailles in early 1919, Article 227 expressly provided for the prosecution of Wilhelm "for a supreme offence against international morality and the sanctity of treaties", but Queen Wilhelmina and the Dutch government refused to extradite him, despite appeals from the Allies. King George V wrote that he looked on his cousin as "the greatest criminal in history", but opposed Prime Minister David Lloyd George's proposal to "hang the Kaiser". President Woodrow Wilson of the United States rejected extradition, arguing that punishing Wilhelm for waging war would destabilize international order and lose the peace.[10]

Restoration of the Kaiserreich

| DNVP German National People's Party | |

|---|---|

| |

| "The monarchical form of government corresponds to the uniqueness and historical development of Germany...we are committed to the renewal of the German empire as established under the Hohenzollerns."[11] |

Wilhelm moved to the municipality of Doorn, to Huis Doorn on 15 May 1920.[13] The Weimar Republic allowed Wilhelm to remove twenty-three railway wagons of packages from the New Palace at Potsdam.[14] In 1922, Wilhelm published the first volume of his memoirs[15]—a very slim volume that insisted he was not guilty of initiating the Great War, and defended his conduct throughout his reign, especially in matters of foreign policy. In the early 1930s, Wilhelm apparently hoped that the successes of the German Nazi Party would stimulate interest in a restoration of the monarchy, with his eldest grandson as the fourth Kaiser.[16] His second wife, Hermine Reuss of Greiz, actively petitioned the Nazi government on her husband's behalf, but the petitions were ignored.

After Hindenburg appointed Hitler as Chancellor in 1933, the Nazi regime restored the Prussian imperial flag. On 21 March 1933, the new Reichstag (Nazi Germany) was constituted with an opening ceremony at the Garrison Church in Potsdam, which was until 1918, the Parish church of the Prussian royal family. This "Day of Potsdam" was held to demonstrate unity between the Nazi movement and the old Prussian elite and military. Hitler appearing in a morning coat and humbly greeting Hindenburg. [17][18] After the deposed heir of Wilhelm II; Crown Prince Wilhelm joined the Stahlhelm which merged in 1931 into the Harzburg Front, Adolf Hitler visited the former Crown Prince at Cecilienhof three times, in 1926, in 1933 (on the "Day of Potsdam") and in 1935.[19] In September 1939, Kaiser Wilhelm's adjutant, General von Dommes, wrote on his behalf to Hitler, stating that the House of Hohenzollern "remained loyal" stating nine Prussian Princes (one son and eight grandchildren) were stationed at the front, concluding "because of the special circumstances that require residence in a neutral foreign country, His Majesty must personally decline to make the aforementioned comment. The Emperor has therefore charged me with making a communication."[20]

In March 1939, Hitler demanded the return of the Danzig and the Polish Corridor, a strip of land that separated East Prussia from the rest of Germany.[21] German forces then invaded Poland, which was Hitler's first military action which started WWII, also restoring Wilhelm's Prussian territories lost in 1918. Wilhelm greatly admired the success Hitler was able to achieve in the opening months of World War II, and personally sent a congratulatory telegram when the Netherlands surrendered in May 1940: "My Fuhrer, I congratulate you and hope that under your marvellous leadership the German monarchy will be restored completely."

| “ | Just as the Bismarck Empire arose from the year 1866, so too will the Greater Germanic Empire arise from this day. Adolf Hitler. 9 April 1940[22] |

” |

In another telegram to Hitler upon the fall of Paris a month later, Wilhelm stated "Congratulations, you have won using my troops." In a letter to his daughter Victoria Louise, Duchess of Brunswick, he wrote triumphantly, "Thus is the pernicious Entente Cordiale of Uncle Edward VII brought to nought."[23] Nevertheless, after the Nazi conquest of the Netherlands in 1940, the aging Wilhelm retired completely from public life. In May 1940, when Hitler invaded the Netherlands, Wilhelm declined an offer from Winston Churchill, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of asylum in the United Kingdom, preferring to die at Huis Doorn on 4 June 1941. .[24] In a letter of 1940 to his sister, Wilhelm wrote: "The hand of God is creating a new world & working miracles... We are becoming the U.S. of Europe under German leadership, a united European Continent." ."[20]

Hohenzollern claims (post 1919)

.png)

William, German Crown Prince was first son and heir of Prussia and the collective Kaiserreich of Kaiser Wilhelm II. The Crown Prince is known to have abdicated around the same time as his father in 1918. Prince William was a military commander, as second in command to his Commander in Chief father, with Generalfeldmarschall Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria and Generalfeldmarschall Albrecht, Duke of Württemberg, at German military headquarters throughout WWI, until the allied armistice of 11/11/1918. As such, Wilhelm II and Crown Prince William directly commanded their Chief of General Staff, General Paul von Hindenburg throughout WWI. In 1933, von Hindenburg appointed (Nazi Party Leader) Hitler as the new Chancellor of Germany. On Hindenburg's death, Hitler officially became Führer and Chancellor of the Realm/Reich. Previously in Germany (1871-1918), the Chancellor was only responsible to the Prussian Kaiser (as Leader of the reich). In 1933, the Nazi regime abolished the flag of the Weimar Republic, and officially restored the Imperial Prussian flag, alongside the Swastika.

An earlier meeting with a (later) senior Nazi figure occurred in 1916, when Crown Prince William invested Herman Göring with his Iron Cross, first class, after Göring flew reconnaissance and bombing missions in a Feldflieger Abteilung 25 (FFA 25) – in Crown Prince William's Fifth Army.[26] Like many veterans, Göring believed the Stab-in-the-back legend, that the WWI German Army had not really lost the war, but was betrayed by Marxists, Jews, and especially Republicans, who had overthrown the German monarchy.[27] In 1933, with Hitler and the Nazi Party in power, Göring was appointed as Minister of the Interior for Prussia,[28] for which he established a Prussian police force called the Geheime Staatspolizei, or Gestapo.[29] The headquarters of Reich Main Security Office, SD, Gestapo and SS in Nazi Germany (1933-1945), was symbolically housed at Prinz Albrecht -Strasse, off Wilhelm -straße, in Berlin.

In the early 1930s, Wilhelm II apparently hoped the successes of the German Nazi Party would stimulate interest in a restoration of the monarchy, with Crown Prince William's son as the fourth Kaiser.[16] After Crown Prince Wilhelm joined the Stahlhelm which merged in 1931 into the Harzburg Front, Adolf Hitler visited the former Crown Prince at Cecilienhof three times, in 1926, in 1933 (on the "Day of Potsdam") and in 1935.[19] In May 1940, Prince Wilhelm of Prussia, the son of Crown Prince William, nominated by Wilhelm as the fourth Kaiser, took part in the invasion of France. He was wounded during the fighting in Valenciennes and died on 26 May 1940. The service drew over 50,000 mourners.[30] His death and the ensuing sympathy of the German public toward a member of the former German royal house greatly bothered Hitler, and he began to see the Hohenzollerns as a threat to his power. In 1940 Hitler issued the Prinzenerlass, prohibiting princes from German royal houses from military service the Wehrmacht,[30] but did not prohibit membership of military SA & SS units which many princes joined.

Prince August Wilhelm of Prussia was the fourth son of Emperor Wilhelm II, by his first wife, Augusta Victoria. In 1933 August Wilhelm had a position in the Prussian state, and became a member of the German Reichstag. The former prince hoped "that Hitler would one day hoist him or his son Alexander up to the vacant throne of the Kaiser". In 1939 August Wilhelm was made an SA-Obergruppenführer, the second highest SA rank. Translated as "senior group leader",[31]Obergruppenführer was a Nazi Party paramilitary rank first created in 1932 as a rank of the SA, and adopted by the Schutzstaffel one year later. Until 1942, it was the highest commissioned SS rank, inferior only to Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler.

As listed, Prince August was given Nazi Party membership number 24, at number 12 was SS-Obergruppenführer Philipp Bouhler. He was a SS-Reichsleiter, (same SS rank as Himmler and Goebbels), he was 2nd only to the rank of the Führer in NASDAP. Philipp Bouhler, worked alongside Philipp, Landgrave of Hesse who was a close friend of Göring. Bouhler was head of Nazi Action T4 euthanasia program for children and the handicapped; (70,000 murders). Deputy Führer to Hitler, also ranked SS-Obergruppenführer, and also SS-Reichsleiter, Rudolf Hesse was number 14. Hesse and Hitler, like Göring, held a shared belief in the stab-in-the-back myth, that Germany's loss in WWI was caused by a conspiracy of Jews and Bolsheviks rather than a military defeat.[32][33]

After the death of Prince August's father, Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1942, more so after making derogatory remarks about Joseph Goebbels, Prince August was denounced in 1942, side-lined and also banned from making public speeches. In 1945, with former Crown Princess Cecilie, August Wilhelm fled the approaching Red Army to Kronberg to take refuge with his aunt Princess Margaret of Prussia.

Prince Alexander Ferdinand was the only son of Prince August Wilhelm and his wife Princess Alexandra Victoria.[34] In 1939, Prince Alexander was a first lieutenant in the Air Force Signal Corps.[35][36][37] Like his father, Prince August hope that Hitler "would one day hoist him, or his son, up to the vacant throne of the Kaiser". Prince Alexander and his fathers support for the Nazis, caused disagreements among the Hohenzollerns, with Wilhelm II urging them both to leave the Nazi party.[38] In 1933, Prince Alexander quit the SA and became a private in the German regular army.[39] In 1934, Berlin leaked out that the prince quit the SA because Hitler had chosen 21-year-old Alexander Ferdinand to succeed him as "head man in Germany when he [Hitler] no longer can carry the torch".[39] The report said Joseph Goebbels was expected to oppose the prince's nomination.[39] Unlike many princes untrusted and removed from their commands by Hitler, Prince Alexander was the only Hohenzollern allowed to remain at his post.[40]

| NSDAP | Nazi Party | Military Rank | Title and Name | Royal House | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSDAP - 24 | Joined: 1/4/1930 |   | Prince August Wilhelm of Prussia |  |  |

| NSDAP - 534782 | Joined: 1/5/1931 |   | Prince Alexander Ferdinand of Prussia |  |  |

| NSDAP - 2407422 | Joined: 1/5/1935 |  | Prince Karl Franz of Prussia |  |  |

Abolished federal princedoms of the Kaiserreich

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- ↑ Harper's Magazine, Volume 63. P. 593. The term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people, the term "Kaiserreich" literally denotes an empire - particularly a hereditary empire led by a literal emperor, though Reich has been used in German to denote the Roman Empire because it has a weak hereditary tradition. In the case of the German Empire, the official name was Deutsches Reich that is properly translated as "German Realm" because the official position of head of state in the constitution of the German Empire was officially a "presidency" of a confederation of German states led by the King of Prussia who would assume "the title of German Emperor" as referring to the German people but was not emperor of Germany as in an emperor of a state.

- ↑ Article 109 of the Weimar Constitution constitutes: Adelsbezeichnungen gelten nur als Teil des Namens und dürfen nicht mehr verliehen werden ("Noble names are only recognised as part of the surname and may no longer be granted").

- ↑ The American Year Book: A Record of Events and Progress. 1919. p. 153.

- ↑ Statement of Abdication (1918). As translated and appearing in the 1923 Source Records of the Great War, Vol. VI, edited by Charles F. Horne.

- ↑ "Biografie Prinz Max von Baden (German)". Deutsches Historisches Museum. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- 1 2 "Biografie Prinz Max von Baden (German)". Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Haffner, Sebastian (2002). Die deutsche Revolution 1918/19 (German). Kindler. ISBN 3-463-40423-0.

- ↑ Cecil 1996, vol. 2 p. 292.

- ↑ Cecil 1996, vol. 2 p. 294.

- ↑ Ashton & Hellema 2000, pp. 53–78.

- ↑ German National People's Party Program pages 348-352 from The Weimar Republic Sourcebook edited by Anton Kaes, Martin Jay and Edward Dimendberg, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1994 page 349.

- ↑ Beck, Hermann The Fateful Alliance: German Conservatives and Nazis in 1933 Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2009, pp. 47–48. "Westarp continued to maintain that he was a monarchist utterly committed to restoring the House of Hohenzollern while his party was participating in a republican government".

- ↑ Macdonogh 2001, p. 426.

- ↑ Macdonogh 2001, p. 425.

- ↑ Hohenzollern 1922.

- 1 2 RADOWITZ-NEI.Copyright, BARON CLEMENS VON (3 July 1922). "MONARCHY WILL RETURN, BUT NOT I, SAYS EX-KAISER; Ebert Capable, but Republic Is Only a Temporary Affair, Former Ruler Holds. SEES NATION AGAIN A POWER Hopes for an Economic Union in Central Europe, but Disapproves Austrian Alliance.ASSAILS THE SOVIET TREATYTslka on Many Current Issues With Baron Clemens von Radowitz-Nel, One of a Group Of Callers at Doorn.". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- ↑ City of Potsdam.

- ↑ Shirer 1960, pp. 196–197.

- 1 2 Müller, Heike; Berndt, Harald (2006). Schloss Cecilienhof und die Konferenz von Potsdam 1945 (German). Stiftung Preussische Schlösser und Gärten. ISBN 3-910068-16-2.

- 1 2 Petropoulos 2006, p. 170.

- ↑ Kershaw 2008, p. 486.

- ↑ Sager & Winkler 2007, p. 74.

- ↑ Palmer 1978, p. 226.

- ↑ Martin 1994, p. 523.

- ↑ Showalter, D. E., Tannenberg: Clash of Empires. Hamden: Archon, 1991. p 177

- ↑ Manvell 2011, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Manvell 2011, p. 39.

- ↑ Manvell 2011, p. 92.

- ↑ Evans 2005, p. 54.

- 1 2 "Wilhelm Prinz von Preussen (in German)" (in German). Preussen.de. Retrieved 2008-07-12.

- ↑ McNab (II) 2009, p. 15.

- ↑ Nesbit & van Acker 2011, p. 15.

- ↑ Evans 2003, p. 177.

- ↑ Lundy, Darryl. "The Peerage: Alexander Ferdinand Prinz von Preußen". Retrieved 13 December 2010.

- 1 2 "Family of Ex-Kaiser Sends Many to Front", The New York Times, 26 November 1939

- 1 2 Associated Press (26 November 1939), "Kaiser's Kin Serve Hitler In Nazi Army", The Washington Post (Berlin)

- 1 2

- ↑ MacDonogh, Giles (2000). The Last Kaiser: The Life of Wilhelm II. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 449.

- 1 2 3 4 Prince Chosen by Hitler as Reich Regent (PDF), 2 January 1934, pp. Tonawanda Evening News

- ↑ Petropoulos, Jonathan (2006). Royals and the Reich: The Princes von Hessen in Nazi Germany. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 243.

- ↑ "Kaiser's Grandson is Killed in Action", The New York Times (Berlin), 17 September 1939

Bibliography

- Ashton, Nigel J; Hellema, Duco (2000), "Hanging the Kaiser: Anglo-Dutch Relations and the Fate of Wilhelm II, 1918–20", Diplomacy & Statecraft 11 (2): 53–78, doi:10.1080/09592290008406157, ISSN 0959-2296.

- Cecil, Lamar (1996), Wilhelm II: Emperor and Exile, 1900–1941, ISBN 0-8078-2283-3.

- Hohenzollern, William II (1922), My Memoirs: 1878–1918, London: Cassell & Co, Google Books.

- Kershaw, Ian (2008). Hitler: A Biography. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06757-6.

- Klee, Ernst: Das Personenlexikon zum Dritten Reich. Wer war was vor und nach 1945. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Zweite aktualisierte Auflage, Frankfurt am Main 2005 ISBN 978-3-596-16048-8

- Klee, Ernst Das Kulturlexikon zum Dritten Reich. Wer war was vor und nach 1945. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2007 ISBN 978-3-10-039326-5

- Macdonogh (2001), The Last Kaiser: William the Impetuous, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, ISBN 978-1-84212-478-9.

- Palmer, Alan (1978), The Kaiser: Warlord of the Second Reich, Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Shirer, William L. (1960). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-62420-0.

- Stein, Harry (2004). Buchenwald concentration camp 1937–1945. Wallstein Verlag. ISBN 3-89244-695-4.

External links

- * The German Emperor as shown in his public utterances

- The German emperor's speeches: being a selection from the speeches, edicts, letters, and telegrams of the Emperor William II

- Works by or about Kaiserreich abdication of Wilhelm II at Internet Archive, mostly in German

-

"William II. of Germany". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

"William II. of Germany". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911. - The Last German Emperor, Living in Exile in The Netherlands 1918-1941 on YouTube

- Historical film documents on Wilhelm II from the time of World War I at European Film Gateway

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

-de.svg.png)