Franz Wilhelm Junghuhn

| Franz Wilhelm Junghuhn | |

|---|---|

Photograph taken in 1860. | |

| Born |

October 26, 1809 Mansfeld, Germany |

| Died |

April 24, 1864 Lembang, West Java |

| Nationality | German-born Dutch |

| Occupation | Botanist and geologist |

Friedrich Franz Wilhelm Junghuhn (October 26, 1809 in Mansfeld, Germany – April 24, 1864 in Lembang, Bandung, West Java), was a German-Dutch botanist and geologist. His father, Friedrich Junghuhn was a barber and a surgeon. His mother was Christine Marie Schiele. Junghuhn studied medicine in Halle and in Berlin from 1827 to 1831, meanwhile (1830) publishing a seminal paper on mushrooms in Limnaea. Ein Journal für Botanik.

Early life

As a student Junghuhn was given to bouts of depression and he attempted suicide. He became involved in a 'matter of honor', and in the ensuing duel was himself hit, but perhaps unknown to him his opponent died of his wounds. Junghuhn fled by taking service in the Prussian army as a surgeon but was discovered and sentenced to ten years in prison. He feigned insanity, and was able to escape in the Autumn of 1833. He was briefly a member of the French Foreign Legion in North Africa but was dismissed on account of his poor health. At Paris, he sought out the famed Dutch botanist Christian Hendrik Persoon, who recommended that Junghuhn "enlist in the Dutch colonial army, and have yourself sent to the Dutch East Indies as a medical doctor".[1] Junghuhn did so, leaving Europe (Hellevoetsluis) in the early Summer of 1835, arriving in Jakarta (then called "Batavia") on October 13, 1835.

Java

Junghuhn settled on Java, where he made an extensive study of the land and its people. He discovered the Kawah Putih crater lake south of Bandung in 1837. He published extensively on his many often highly adventurous expeditions and his scientific analyses. Among his works is an important description and natural history in many volumes of the volcanoes of Java, Bijdragen tot de geschiedenis der vulkanen in den Indischen Archipel (1843). He completed Die Topographischen und Naturwissenschaftlichen Reisen durch Java (Topographic and Scientific Journeys in Java) in 1845 and a first anthropological and topographical study of Sumatra, Die Bättalander auf Sumatra (Batak lands of Sumatra). in 1847. In 1849, ill health forced his return to the Netherlands, where he married Johanna Louisa Frederika Koch on January 23, 1850, and had a son. While in the Netherlands, Junghuhn began work on a four volume treatise published in Dutch and translated into German between 1850 and 1854: Java, deszelfs gedaante, bekleeding en inwendige struktuur (in German: Java, seine Gestalt, Pflanzendecke, und sein innerer Bau). Junghuhn was an avid humanist and socialist. In the Netherlands he published anonymously his free-thinking manifesto Licht- en Schaduwbeelden uit de Binnenlanden van Java (Images of Light and Shadow from Java's interior) between 1853 and 1855. The work was controversial, advocating socialism in the colonies and fiercely criticizing Christian and Islamic proselytization of the Javanese people. Junghuhn instead wrote of his preference for a form of Pandeism (pantheistic deism), contending that God was in everything, but could only be determined through reason. The work was banned in Austria and parts of Germany for its "denigrations and vilifications of Christianity", but was a strong seller in the Netherlands where it was first published pseudonymously. It was also popular in colonial Indonesia, despite opposition from the Dutch Christian Church there. The publisher of the first volume, Jacobus Hazenberg, refused to continue his association with the work; the remaining four were published by the outspoken liberal, Frans Günst, from volume three as installments (from October 1, 1855) of the newly founded journal for freethinkers, De Dageraad (Dawn).

Recovered from his ills, Junghuhn returned to Java in 1855. Highly interested in botany and its practical applications, he (together with J.E. de Vrij of Bandung) became embroiled in a bitter and extended controversy with Johannes Elias Teijsmann, hortulanus of 's Lands Plantentuin at Buitenzorg (now Bogor) and J.C. Hasskarl about the effectiveness of Cinchona species in the treatment of malaria. This controversy was conducted in public and in print with open letters to and demands on "Het Natuurkundig Genootschap"; part of this exchange of minds can be followed in Natuurkundig Tijdschrift voor Nederlandsch Indië from 1862 onwards. At his direction massive plantation of Chincocina was carried out in Java, making it leading producer of Kina (Chinocina bark). He remained on Java until his death from liver disease in 1864. On his deathbed in his house near Lembang on the slopes of the volcano Tangkuban Perahu just north of Bandung, Java, Junghuhn asked the doctor to open the windows, so he could say goodbye to the mountains that he loved. In Lembang there is a small monument to his memory in a grassy square named after him planted with some of his favorite trees among which the Cinchona. A minor item of trivia playing into polemical discussions of Junghuhn is his surname, literally translated as "young chicken".

The plants Cyathea junghuhniana and Nepenthes junghuhnii are named after Franz Junghuhn.

Gallery of Junghuhn's Drawing

-

The Pyramids of Giza

-

Patengan Lake.

-

Southern coast of Java

-

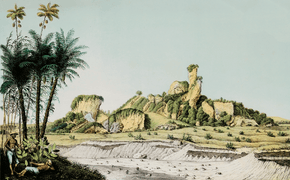

Candi Sebu

-

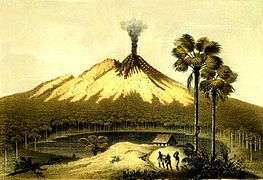

Junghuhn in Mount Merapi

-

The island Pontjang Kitjil (Poncang Kecil) in Tapanulibaai (now Teluk Sibolga)

References

- ↑ J. P. Poley, Eroica: The Quest for Oil in Indonesia (1850-1898) (2000) p. 26.

Bibliography

- Franz Junghuhn. Biographische Beiträge zur 100. Wiederkehr seines Geburtstages, ed. Max. C.P. Schmidt, Leipzig: Dürr'schen Buchhandlung, 1909.

- F. Junghuhn. Gedenkboek 1809-1909, De Junghuhn-Commissie, 's-Gravenhage: Martinus Nijhoff, 1910.

- Java's onuitputtelijke natuur. Reisverhalen, tekeningen en fotografieën van Franz Wilhelm Junghuhn, ed. Rob Nieuwenhuys and Frits Jaquet, Alphen aan den Rijn: A.W. Stijthof, 1980.

A curious 'scientific' novel about Junghuhn's life is: C.W. Wormser, Frans Junghuhn, Deventer: W. van Hoeve, 1942.

External links

|