José Maria de Eça de Queirós

| José Maria de Eça de Queirós | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

25 November 1845 Póvoa de Varzim, Portugal |

| Died |

16 August 1900 (aged 54) Paris, France |

| Occupation | Novelist/Consul |

| Nationality | Portuguese |

| Literary movement | Realism, Romanticism |

|

| |

| Signature |

|

José Maria de Eça de Queiroz [1] (European Portuguese: [ʒuˈzɛ mɐˈɾiɐ dɨ ˈɛsɐ dɨ kejˈɾɔʃ]; 25 November 1845 – 16 August 1900) is generally considered to be the greatest Portuguese writer in the realist style.[2] Zola considered him to be far greater than Flaubert.[3] The London Observer critics rank him with Dickens, Balzac and Tolstoy.[4] Eça never officially rejected Catholicism, and in many of his private letters he even invokes Jesus and uses expressions typical of Catholics, but was very critical of the Catholic Church of his time, and of Christianity in general (also Protestant churches) as is evident in some of his novels.

During his lifetime, the spelling was "Eça de Queiroz" and this is the form that appears on many editions of his works; the modern standard Portuguese spelling is "Eça de Queirós".

Biography

Eça de Queirós was born in Póvoa de Varzim, Portugal, in 1845. An illegitimate child, he was officially recorded as the son of José Maria de Almeida Teixeira de Queirós and Carolina Augusta Pereira d'Eça.

At age 16, he went to Coimbra to study law at the University of Coimbra; there he met the poet Antero de Quental. Eça's first work was a series of prose poems, published in the Gazeta de Portugal magazine, which eventually appeared in book form in a posthumous collection edited by Batalha Reis entitled Prosas Bárbaras ("Barbarous texts"). He worked as a journalist at Évora, then returned to Lisbon and, with his former school friend Ramalho Ortigão and others, created the Correspondence of the fictional adventurer Fradique Mendes. This amusing work was first published in 1900.

In 1869 and 1870, Eça de Queirós travelled to Egypt and watched the opening of the Suez Canal, which inspired several of his works, most notably O Mistério da Estrada de Sintra ("The Mystery of the Sintra Road", 1870), written in collaboration with Ramalho Ortigão, in which Fradique Mendes appears. A Relíquia ("The Relic") was also written at this period but was published only in 1887. The work was strongly influenced by Memorie di Giuda ("Memoirs of Judas") by Ferdinando Petruccelli della Gattina, such as to lead some scholars to accuse the Portuguese writer of plagiarism.[5]

When he was later dispatched to Leiria to work as a municipal administrator, Eça de Queirós wrote his first realist novel, O Crime do Padre Amaro ("The Sin of Father Amaro"), which is set in the city and first appeared in 1875.

Eça then worked in the Portuguese consular service and after two years' service at Havana was stationed, from late 1874 until April 1879, at 53 Grey Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, where there is a memorial plaque in his honour.[6] His diplomatic duties involved the dispatch of detailed reports to the Portuguese foreign office concerning the unrest in the Northumberland and Durham coalfields - in which, as he points out, the miners earned twice as much as those in South Wales, along with free housing and a weekly supply of coal. The Newcastle years were among the most productive of his literary career. He published the second version of O Crime de Padre Amaro in 1876 and another celebrated novel, O Primo Basílio ("Cousin Bazilio") in 1878, as well as working on a number of other projects. These included the first of his "Cartas de Londres" ("Letters from London") which were printed in the Lisbon daily newspaper Diário de Notícias and afterwards appeared in book form as Cartas de Inglaterra. As early as 1878 he had at least given a name to his masterpiece Os Maias ("The Maias"), though this was largely written during his later residence in Bristol and was published only in 1888. There is a plaque to Eça in that city and another was unveiled in Grey Street, Newcastle, in 2001 by the Portuguese ambassador.

Eça, a cosmopolite widely read in English literature, was not enamoured of English society, but he was fascinated by its oddity. In Bristol he wrote: "Everything about this society is disagreeable to me - from its limited way of thinking to its indecent manner of cooking vegetables." As often happens when a writer is unhappy, the weather is endlessly bad. Nevertheless, he was rarely bored and was content to stay in England for some fifteen years. "I detest England, but this does not stop me from declaring that as a thinking nation, she is probably the foremost." It may be said that England acted as a constant stimulus and a corrective to Eça’s traditionally Portuguese Francophilia.

In 1888 he became Portuguese consul-general in Paris. He lived at Neuilly-sur-Seine and continued to write journalism (Ecos de Paris, "Echos from Paris") as well as literary criticism. He died in 1900 of either tuberculosis or, according to numerous contemporary physicians, Crohn's disease.[7] His son António Eça de Queirós would hold government office under António de Oliveira Salazar.

Works by Eça de Queirós

- O Mistério da Estrada de Sintra ("The Mystery of the Sintra Road", 1870, in collaboration with Ramalho Ortigão)

- O Crime do Padre Amaro ("The Sin of Father Amaro", 1875, revised 1876, revised 1880)

- A Tragédia da Rua das Flores ("The Rua das Flores (Flower's Street) Tragedy") (1877-1878)

- O Primo Basílio ("Cousin Bazilio", 1878)

- O Mandarim ("The Mandarin", 1880)

- As Minas de Salomão, translation of H. Rider Haggard's King Solomon's Mines (1885)

- A Relíquia ("The Relic", 1887)

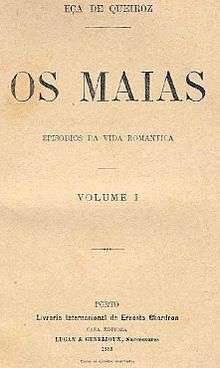

- Os Maias ("The Maias", 1888)

- Uma Campanha Alegre ("A Cheerful Campaign") (1890-1891)

- Correspondence of Fradique Mendes,1890

- A Ilustre Casa de Ramires ("The Noble House of Ramires", 1900)

Posthumous works

- A Cidade e as Serras ("The City and the Hills", 1901, Posthumous)

- Contos ("Stories") (1902, Posthumous)

- Prosas Bárbaras ("Barbarous Texts", 1903, Posthumous)

- Cartas de Inglaterra ("Letters from England") (1905, Posthumous)

- Ecos de Paris ("Echos from Paris") (1905, Posthumous)

- Cartas Familiares e Bilhetes de Paris ("Family Letters and Notes from Paris") (1907, Posthumous)

- Notas Contemporâneas ("Contemporary Notes") (1909, Posthumous)

- Últimas páginas ("Last Pages") (1912, Posthumous)

- A Capital ("The Capital") (1925, Posthumous)

- O Conde d'Abranhos ("The Earl of Abranhos") (1925, Posthumous)

- Alves & C.a ("Alves & Co.", published in English as "The Yellow Sofa", 1925, Posthumous)

- O Egipto ("Egypt", 1926, Posthumous)

Periodicals to which Eça de Queirós contributed

- Gazeta de Portugal

- As Farpas ("Barbs")

- Diário de Notícias

Translations

His works have been translated into about 20 languages, including English.

Since 2002 English versions of six of his novels and a volume of short stories, translated by Margaret Jull Costa, have been published in the UK by Dedalus Books.

- A capital (The Capital): translation by John Vetch, Carcanet Press (UK), 1995.

- A Cidade e as serras (The City and the Mountains): translation by Roy Campbell, Ohio University Press, 1968.

- A Ilustre Casa de Ramires (The illustrious house of Ramires): translation by Ann Stevens, Ohio University Press, 1968.

- A Relíquia (The Relic): translation by Aubrey F. Bell, A. A. Knopf, 1925. Also published as The Reliquary, Reinhardt, 1954.

- A Relíquia (The Relic): translation by Margaret Jull Costa, Dedalus Books, 1994.

- A tragédia da rua das Flores (The Tragedy of the Street of Flowers): translation by Margaret Jull Costa, Dedalus Books, 2000.

- Alves & Cia (Alves & Co.): translation by Robert M. Fedorchek, University Press of America, 1988.

- Cartas da Inglaterra (Letters from England): translation by Ann Stevens, Bodley Head, 1970. Also published as Eça's English Letters, Carcanet Press, 2000.

- O Crime do Padre Amaro (El crimen del Padre Amaro): Versión de Ramón del Valle - Inclan, Editorial Maucci, 1911

- O Crime do Padre Amaro (The Sin of Father Amaro): translation by Nan Flanagan, St. Martins Press, 1963. Also published as The Crime of Father Amaro, Carcanet Press, 2002.

- O Crime do Padre Amaro (The Crime of Father Amaro): translation by Margaret Jull Costa, Dedalus Books, 2002.

- O Mandarim (The Mandarin in The Mandarin and Other Stories): translation by Richard Frank Goldman, Ohio University Press, 1965. Also published by Bodley Head, 1966; and Hippocrene Books, 1993.

- Um Poeta Lírico (A Lyric Poet in The Mandarin and Other Stories): translation by Richard Frank Goldman, Ohio University Press, 1965. Also published by Bodley Head, 1966; and Hippocrene Books, 1993.

- Singularidades de uma Rapariga Loura (Peculiarities of a Fair-haired Girl in The Mandarin and Other Stories): translation by Richard Frank Goldman, Ohio University Press, 1965. Also published by Bodley Head, 1966; and Hippocrene Books, 1993.

- José Mathias (José Mathias in The Mandarin and Other Stories): translation by Richard Frank Goldman, Ohio University Press, 1965. Also published by Bodley Head, 1966; and Hippocrene Books, 1993.

- O Mandarim (The Mandarin in The Mandarin and Other Stories): translation by Margaret Jull Costa, Hippocrene Books, 1983.

- O Mandarim (The Mandarin in The Mandarin and Other Stories): translation by Margaret Jull Costa, Dedalus Books, 2009.

- José Mathias (José Mathias in The Mandarin and Other Stories): translation by Margaret Jull Costa, Dedalus Books, 2009.

- O Defunto (The Hanged Man in The Mandarin and Other Stories): translation by Margaret Jull Costa, Dedalus Books, 2009.

- Singularidades de uma Rapariga Loura (Idiosyncrasies of a young blonde woman in The Mandarin and Other Stories): translation by Margaret Jull Costa, Dedalus Books, 2009.

- O Primo Basílio (Dragon's teeth): translation by Mary Jane Serrano, R. F. Fenno & Co., 1896.

- O Primo Basílio (Cousin Bazilio): translation by Roy Campbell, Noonday Press, 1953.

- O Primo Basílio (Cousin Bazilio): translation by Margaret Jull Costa, Dedalus Books, 2003.

- Suave milagre (The Sweet Miracle): translation by Edgar Prestage, David Nutt, 1905. Also published as The Fisher of Men, T. B. Mosher, 1905; The Sweetest Miracle, T. B. Mosher, 1906; The Sweet Miracle, B. H. Blakwell, 1914.

- Os Maias (The Maias): translation by Ann Stevens and Patricia McGowan Pinheiro, St. Martin's Press, 1965.

- Os Maias (The Maias): translation by Margaret Jull Costa, New Directions, 2007.

- O Defunto (Our Lady of the Pillar): translation by Edgar Prestage, Archibald Constable, 1906.

- Pacheco (Pacheco): translation by Edgar Prestage, Basil Blackwell, 1922.

- A Perfeição (Perfection): translation by Charles Marriott, Selwyn & Blovnt, 1923.

- José Mathias (José Mathias in José Mathias and A Man of Talent): translation by Luís Marques, George G. Harap & Co., 1947.

- Pacheco (A man of talent in José Mathias and A Man of Talent): translation by Luís Marques, George G. Harap & Co., 1947.

- Alves & Cia (The Yellow Sofa in Yellow Sofa and Three Portraits): translation by John Vetch, Carcanet Press, 1993. Also published by New Directions, 1996.

- Um Poeta Lírico (Lyric Poet in Yellow Sofa and Three Portraits): translation by John Vetch, Carcanet Press, 1993. Also published by New Directions, 1996.

- José Mathias (José Mathias in Yellow Sofa and Three Portraits): translation by Luís Marques, Carcanet Press, 1993. Also published by New Directions, 1996.

- Pacheco (A man of talent in Yellow Sofa and Three Portraits): translation by Luís Marques, Carcanet Press, 1993. Also published by New Directions, 1996.

Adaptations

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eça de Queirós. |

There have been two film versions of O Crime do Padre Amaro, a Mexican one in 2002 and a Portuguese version in 2005 which was edited out of a SIC television series, released shortly after the film (the film was by then the most seen Portuguese movie ever, though very badly received by critics, but the TV series, maybe due to being a slightly longer version of the same thing seen by a big share of Portuguese population, flopped and was rather ignored by audiences and critics).

Eça's works have been also adapted on Brazilian television. In 1988 Rede Globo produced O Primo Basílio in 35 episodes. Later, in 2007, a movie adaptation of the same novel was made by director Daniel Filho. In 2001 Rede Globo produced an acclaimed adaptation of Os Maias as a television serial in 40 episodes.

A movie adaptation of O Mistério da Estrada de Sintra was produced in 2007.[8] The director had shortly before directed a series inspired in a whodunit involving the descendants of the original novel's characters (Nome de Código Sintra, Code Name Sintra), and some of the historical flashback scenes (reporting to the book's events) of the series were used in the new movie. The movie was more centered on Eça's and Ramalho Ortigão's writing and publishing of the original serial and the controversy it created and less around the book's plot itself.

References

Notes

- ↑ His last name was officially spelled "Queiroz"; as Queirós is the most common spelling nowadays, the author is sometimes referred to as "Eça de Queirós"

- ↑ Pick of the week - Consul yourself, Nicholas Lezard, The Guardian, 23 December 2000

- ↑ backcover of The crime of Father Amaro: scenes of the religious life

- ↑ The Maias, by Eca de Queiros, New Directions Publishing Corp Archived 4 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Cláudio Basto, Foi Eça de Queirós um plagiador?, Maranus, 1924, p.70

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ filmesfundo.com

Bibliography

- Theatre Adaptations: 'Galleon Theatre Company', the resident producing company at the 'Greenwich Playhouse' (London), has staged internationally acclaimed theatre adaptations, by Alice de Sousa and directed by Bruce Jamieson, of Eça de Queirós' novels. In 2001, the company presented 'Cousin Basílio' and in 2002 'The Maias'. From 8 March to 3 April 2011 the company are reviving their greatly acclaimed production of 'The Maias' at the 'Greenwich Playhouse'.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: José Maria Eça de Queirós |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Eça de Queiroz, José Maria. |

- About Eça de Queirós (formerly Queirós, but out of date)

- Works by José Maria de Eça de Queirós at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about José Maria de Eça de Queirós at Internet Archive

- Works by José Maria de Eça de Queirós at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Petri Liukkonen. "José Maria de Eça de Queirós". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Archived from the original on 4 July 2013.

- Book: New edition of "The Relic" by Eça de Queirós published – Tagus Press, UMD Portuguese American Journal

- (Portuguese) (English) Queirós's/Queirós's Idealism & Realism (idealismo e realismo)

- The sweet miracle, and English translation of Suave milagre

| ||||||||||

|