Jim Leslie (Louisiana)

| James S. "Jim" Leslie | |

|---|---|

|

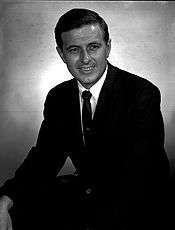

The Shreveport Times photo of Jim Leslie in the Louisiana State University in Shreveport Archive | |

| Born |

October 27, 1937 Place of birth missing |

| Died |

July 9, 1976 (aged 38) Baton Rouge, Louisiana, USA |

| Cause of death | Unsolved assassination |

| Resting place | Forest Park East Cemetery in Shreveport, Louisiana |

| Residence | Shreveport, Louisiana |

| Alma mater | Missing |

| Occupation |

Journalist for The Shreveport Times |

| Spouse(s) | Married |

| Children | Scott and Mickey Leslie |

James S. Leslie, known as Jim Leslie (October 27, 1937 – July 9, 1976),[1] was a journalist for The Shreveport Times who became a public relations and advertising executive in Shreveport in northwestern Louisiana. His shotgun assassination in the capital city of Baton Rouge led quickly to the collapse of the controversial administration of Shreveport Public Safety Commissioner George W. D'Artois.

D'Artois's advertising man

In 1974, D'Artois hired Leslie to conduct public relations for D'Artois's successful campaign for reelection as the citywide commissioner of public safety, a post to which the Democrat had first been elected in 1962 and encompassed authority over both the police and fire departments. D'Artois twice paid Leslie for his services, the second time under threat, through a Shreveport municipal account; Leslie spurned the checks and asked for proper payment from the campaign fund instead.[2] Leslie also testified before a grand jury investigating corruption in the Shreveport Department of Public Safety.[3]

D'Artois was not Leslie's first client. He had worked successfully in 1972 to elect Democrat J. Bennett Johnston, Jr., of Shreveport to the United States Senate as the long-range successor to the late Allen J. Ellender and in 1975 to make J. Kelly Nix the new Louisiana state superintendent of education through the defeat of incumbent Louis J. Michot.[3]

Assassination

In the summer of 1976, Leslie was involved with the forces led by Edward J. Steimel of the Louisiana Association of Business and Industry which passed a right-to-work law through the Louisiana State Legislature in line with Section 14b of the Taft-Hartley Act, which permits states to outlaw closed shops that require employees of companies to join or pay dues to a labor union. As Leslie came to the Prince Murat Inn at the state capital for a celebration of the legislative breakthrough, he parked in an available distant spot, got out of his car, and walked to the hotel. Author Brad Kozak recounts the horror Leslie quickly faced: "the assailant raised a 12-gauge shotgun loaded with double-ought and fired from about 20 feet behind Leslie. All 16 pellets from the shell penetrated his body, ripping through his heart and lungs with the force of .32 caliber bullets. He died instantly."[2]

Speculation persisted that D'Artois, soon forced from office on multiple corruption charges in Shreveport, hired the assassin who killed Leslie. D'Artois was charged in the Leslie murder but died during open heart surgery in San Antonio, Texas, and hence never faced trial for his role in the case.[4]

Nine days after taking office as the sheriff of Caddo Parish, Harold Terry had the unpleasant duty of informing the Leslie family in Shreveport of Leslie's assassination in the evening of July 9, 1976. Josiah Lee "J. L." Wilson, III (1940-2015),[5] then a reporter for The Shreveport Times reported that deputies told him that Sheriff Terry's eyes were red from weeping as he left his office to meet with Mrs. Carolyn S. Leslie (born April 30, 1934) and the couple's two sons, D. Scott Leslie (born November 11, 1968) and Mickey Leslie, to relay the tragic news. Terry never commented on how the Leslies handled the disclosure in order to protect their privacy.[6] Terry and D'Artois had been deputies together prior to 1962 under then Sheriff J. Howell Flournoy.

Enduring speculation

Years later, James H. "Jim" Brown, a state senator at the time of Leslie's assassination and later the Louisiana Secretary of State, a candidate for governor in 1987, and the state insurance commissioner, reported a chance meeting in March 2006 at a hotel in Bossier City, where he met Leslie's son, presumably Mickey, a bellman whom he did not name but indicated was then thirty-four years of age, hence born c. 1971. Brown subsequently wrote a column in which he recalled that Rusty Griffith was "ultimately tagged as the trigger man" in the case but was himself assassinated a few months later in Brown's own Concordia Parish in eastern Louisiana. "Some say it was to shut [Griffith] up from trying to blackmail D'Artois," said Brown.[4]

The case inspired former Louisiana State Senator Bill Keith, then of Shreveport and later of Longview, Texas, and a journalist with The Shreveport Times and the since defunct Shreveport Journal, to publish in 2009, The Commissioner: A True Story of Deceit, Dishonor, and Death, a study of the D'Artois administration, the commissioner's connection to crime bosses, and the unsolved Leslie murder. In 2014, Jere Joiner, a former Shreveport police officer, published Badge of Dishonor, another look into the corruption of the D'Artois administration. Political pundit and consultant Elliott Stonecipher, a Leslie friend who accompanied the body back to Shreveport, said that he never once doubted that D'Artois was behind the assassination though some had thought the right-to-work controversy may have spurred the crime. Stonecipher said that Leslie had told him prior to the fateful end that he believed D'Artois would try to have him killed.[7]

Brad Kozak called Leslie "a stand-up guy, a good ad man, and a rarity in the advertising game – a man with a conscience."[2] Leslie is interred at Forest Park East Cemetery in Shreveport. So is George W. D'Artois.[1]

The Shreveport-Bossier Advertising Federation awards the annual Jim Leslie Memorial Scholarship in the amount of $1,100 to a freshman student at Louisiana State University in Shreveport studying in the field of communications-related curricula.[8]

References

- 1 2 John Andrew Prime. "James S. "Jim" Leslie". findagrave.com. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Brad Kozak (October 19, 2011). "When Cops Go Bad I: The Tale of George D’Artois". thetruthaboutguns.com. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- 1 2 Elliott Stonecipher (July 5, 2012). "Lessons from the Murder of Jim Leslie". forward-now.com. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- 1 2 James H. "Jim" Brown (March 23, 2006). "Jim Leslie's Murder: Thirty Years Ago (1976) in Baton Rouge" (PDF). jimbrownla.com. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Josiah Lee "J. L." Wilson, III". The Shreveport Times. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- ↑ Bill Keith (2009). The Commissioner: A True Story of Deceit, Dishonor, and Death. Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican Publishing Company. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-58980-655-9. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- ↑ "Badge of Dishonor: George D'Artois and his alleged murder plot against Jim Leslie". KTBS-TV. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Jim Leslie Memorial Scholarship". meritaid.com. Retrieved July 27, 2014.