Jezebel

| Jezebel, Queen of Israel | |

|---|---|

19th-century painting by John Liston Byam Shaw | |

| Religion | Cult of Baal |

| Spouse(s) | King Ahab |

| Children | Ahaziah, Joram, and Athaliah |

| Parent(s) | Ithobaal I |

Jezebel (/ˈdʒɛzəbəl/,[1] Hebrew: אִיזֶבֶל / אִיזָבֶל, Modern Izével / Izável Tiberian ʾÎzéḇel / ʾÎzāḇel) (fl. 9th century BCE) was a princess, identified in the Hebrew Book of Kings (1 Kings 16:31) as the daughter of Ethbaal, King of Sidon (Lebanon/Phoenicia) and the wife of Ahab, king of northern Israel.[2]

According to the Hebrew Bible, Jezebel incited her husband King Ahab to abandon the worship of Yahweh and encourage worship of the deities Baal and Asherah instead. Jezebel persecuted the prophets of Yahweh, and fabricated evidence of blasphemy against an innocent landowner who refused to sell his property to King Ahab, causing the landowner to be put to death. For these transgressions against the God and people of Israel, Jezebel met a gruesome death - thrown out of a window by members of her own court retinue, and the flesh of her corpse eaten by stray dogs.

Jezebel became associated with false prophets. In some interpretations, her dressing in finery and putting on makeup [3] led to the association of the use of cosmetics with "painted women" or prostitutes.

Meaning of name

Jezebel is the Anglicized transliteration of the Hebrew אִיזָבֶל ('Izevel/'Izavel). The Oxford Guide to People & Places of the Bible states that the name is "best understood as meaning 'Where is the Prince?'",[4] a ritual cry from worship ceremonies in honor of Baal during periods of the year when the god was considered to be in the underworld.

Scriptural account

Jezebel's story is told in 1st and 2nd Kings. She was a Phoenician princess, the daughter of Ethbaal, king of Tyre (1 Kings 16:31 says she was “Sidonian”, which is a biblical term for Phoenicians in general).[4] According to genealogies given in Josephus and other classical sources, she was the great-aunt of Dido, Queen of Carthage.[4] Jezebel married King Ahab of the Northern Kingdom (i.e. Israel during the time when ancient Israel was divided into Israel in the north and Judah in the south). Ahab was the son of King Omri, who had brought the northern Kingdom of Israel to great power, established Samaria as his capital, and whose historical existence is confirmed by ancient inscriptions on the Mesha Stele and the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III.[5]

This marriage was the culmination of the friendly relations existing between Israel and Phenicia during Omri's reign, and possibly cemented important political designs of Ahab. Jezebel, like the foreign wives of Solomon, required facilities for carrying on her form of worship, so Ahab made an altar for Baal in the house of Baal, which he had built in Samaria.[6]

Jezebel went so far as to require that her religion should be the national religion of Israel. She organized and maintained guilds of prophets, 450 of Baal, and 400 of Asherah. She also destroyed such prophets of Israel as she could reach. Obadiah, the faithful overseer of Ahab's house, rescued one hundred of these, hid them, and secretly fed them in a cave.[6] Bromiley points out that it was Phoenician practice to install a royal woman as a priestess of Astarte. As such she would have a more active role in temple and palace relations than was customary in the Hebrew monarchy.[7]

Elijah

The prophet Elijah confronted Ahab and charged him with the sin of following Baal. Elijah had two altars set up at Carmel, one dedicated to Baal, one to Yahweh, and a bull sacrificed upon each altar. The supporters of Baal called upon their god to send fire to consume the sacrifice, but nothing happened. When Elijah called on Yahweh, fire came down from heaven immediately and consumed the offering. Elijah ordered the people to seize the prophets of Baal and Asherah, and they were all slaughtered. The superiority of Elijah and of his God in the test at Carmel, and the slaughter of the 450 prophets of Baal and 400 prophets of Asherah, fired the vengeance of Jezebel. Elijah fled for his life to the wilderness, where he mourned the devotion of Israel to Baal and the lack of worshipers of Israel's God.[6]

Naboth

Naboth owned a vineyard near the royal palace in the city of Jezreel. Wishing to acquire Naboth's vineyard so that he could expand his own gardens, Ahab offered to purchase Naboth's vineyard or to give him a better one in exchange, but Naboth refused, saying he could not part with ancestral land. When Jezebel saw that her husband was depressed by this, she arranged for the elders to falsely accuse Naboth of blasphemy and stone him to death. When Ahab took possession of Naboth's vineyard, he was again confronted by Elijah, who prophesied that, owing to the way Ahab and Jezebel had plotted to have Naboth killed, Ahab would die, his royal line would be obliterated, and Jezebel would be eaten by dogs.[8]

Death

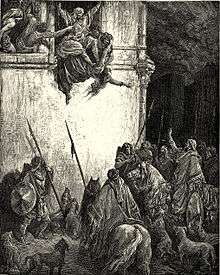

Three years later, Ahab died in battle. His son Ahaziah inherited the throne, but died as the result of an accident and Ahaziah was succeeded by his brother, Joram. Elisha, Elijah's successor, commanded one of his disciples to anoint Jehu, commander of Joram's army, as king, in order that he might destroy Ahab's descendants as a punishment for the way Jezebel had treated God's prophets and his people.[4] Jehu killed Joram and next went to the royal palace at Jezreel, where Jezebel was the last formal obstacle to his kingship.

Knowing that he was coming, Jezebel put on make-up and a formal wig with adornments and looked out a window. Bromiley says that it should be looked at less as an attempt at seduction than the public appearance of the queen mother, invested with the authority of the royal house and cult, confronting a rebellious commander.[7] In his two-volume Guide to the Bible (1967 and 1969), Isaac Asimov describes Jezebel's last act: dressing in all her finery, make-up and jewelry, as deliberately symbolic, indicating her dignity, royal status and determination to go out of this life as a queen.[9]

Jehu ordered her servants to throw her from the window. Her blood splashed on the wall and horses, and Jehu's horse trampled her corpse. He entered the palace where, after he ate and drank, he ordered Jezebel's body to be taken for burial. His servants discovered only her skull, her feet and the palms of her hands - her flesh had been eaten by stray dogs, just as the prophet Elijah had prophesied.[10]

Historicity

According to Israel Finkelstein, the marriage of King Ahab to the daughter of the ruler of the Phoenician empire was a sign of the power and prestige of Ahab and the northern Kingdom of Israel. He termed it a "brilliant stroke of international diplomacy."[5] He says that the inconsistencies and anachronisms in the biblical stories of Jezebel and Ahab mean that they must be considered "more of a historical novel than an accurate historical chronicle."[5] Among these inconsistencies, The two books of Kings are part of the Deuteronomistic history, compiled more than two hundred years after the death of Jezebel. Finkelstein notes that these accounts are "obviously influenced by the theology of the seventh century BCE writers".[5] The compilers of the biblical accounts of Jezebel and her family were writing in the southern kingdom of Judah centuries after the events from a perspective of strict monolatry. These writers considered the polytheism of the members of the Omride dynasty to be sinful. In addition, they were hostile to the northern kingdom and its history, as its center of Samaria was a rival to Jerusalem.[5]

However, other scholars such as Dr J Bimson, of Trinity College, Bristol, argue that 1 and 2 Kings are not 'a straightforward history but a history which contains its own theological commentary'.[11] He points to verses like 1 Kings 14:19 that show the author of Kings was drawing on other earlier sources.

According to Geoffrey Bromiley, the depiction of her as "the incarnation of Canaanite cultic and political practices, detested by Israelite prophets and loyalists, has given her a literary life far beyond the existence of a ninth-century Tyrian princess."[7]

An ancient seal, discovered in 1964, may be inscribed with Jezebel's name.[12][13][14]

Cultural symbol

Through the centuries, the name Jezebel came to be associated with false prophets. By the early 20th century, it was also associated with fallen or abandoned women.[15] In Christian lore, a comparison to Jezebel suggested that a person was a pagan or an apostate masquerading as a servant of God. By manipulation and/or seduction, she misled the saints of God into sins of idolatry and sexual immorality.[16] In particular, Christians associated Jezebel with promiscuity. In modern usage, the name of Jezebel is sometimes used as a synonym for sexually promiscuous and/or controlling women,[17] especially as a racist stereotype of Black women, the Jezebel stereotype.[18]

In popular culture

- Bette Davis starred as an antebellum Southern belle named Julie in New Orleans, Louisiana, in the film Jezebel (1938). Her aunt says the young woman Julie makes her aunt think of "Jezebel, a woman who did evil in the sight of the Lord".[19]

- Frankie Laine recorded "Jezebel" (1951), written by Wayne Shanklin, which became a hit song.[20] The song begins:

If ever the Devil was born without a pair of hornsIt was you, Jezebel, it was you If ever an angel fell

Jezebel, it was you, Jezebel, it was you![21]

- Sade features the song "Jezebel" on the band's 1985 album Promise.

- Chely Wright features a country song "Jezebel" on her 2001 album Never Love You Enough. The song is about another woman trying to woo her man away from her and she tells Jezebel to save her charms because he's not hers yet. There are themes about witchcraft or sorcery and voodoo and cheating.

- 10000 Maniacs recorded a song "Jezebel" as part of their 1992 album Our Time in Eden. Their song is written from the perspective of a woman who has realized that she is no longer in love with her husband and wants to dissolve their marriage.[22]

- Iron & Wine included a song "Jezebel" on their 2005 EP Woman King. It contains many references to the biblical Jezebel, in particular the dogs associated with her death.[23]

- The debut single "Doo Wop (That Thing)" by American R&B/Hip-Hop artist Lauryn Hill features a lyric that refers to the death of Jezebel:

Talking out your neck sayin' you're a ChristianA Muslim sleeping with the gin Now that was the sin that did Jezebel in

Who you gon' tell when the repercussions spin[24]

- In his novel The Caves of Steel (1953, 1954), Isaac Asimov portrayed Jezebel as an ideal wife and woman who, in full compliance with the mores of the time, promoted her religion.[25]

- Paulette Goddard starred as the Biblical queen Jezebel in the film Sins of Jezebel (1953).[26]

- The Gawker offshoot blog Jezebel (launched 2007) concerns mostly feminist issues and women's interests.[27]

- In the speculative fiction novel The Handmaid's Tale (1985) by Margaret Atwood, the brothel is called "Jezebel's" and prostitutes are referred to as "Jezebels."[28]

- The popular historian Lesley Hazleton wrote a revisionist account, Jezebel, The Untold Story of the Bible's Harlot Queen (2004), presenting Jezebel as a sophisticated queen engaged in mortal combat with the fundamentalist prophet Elijah. Hazleton has also written several non-fiction books about the Middle East.[29]

- In the popular children's novel Abomination, written by Robert Swindells, the elder sister is referred to as Jezebel for being promiscuous, and having boyfriends.

- Jezebel's story figures prominently in the novel "Skinny Legs and All" by Tom Robbins.

- Kelly Clarkson referenced Jezebel in I Had A Dream on her album Piece by Piece (2015).[30]

- Jean Plaidy wrote a historical novel in 1953 about the last years of Catherine de' Medici, titled Queen Jezebel.

- In Hannibal (TV Series) Episode 7 of Season 3, 'Digestivo,' a parallel is made between Jezebel and character Mason Verger. "You recall dogs ate her face." [31]

References

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, Second Edition.

- ↑ Elizabeth Knowles, "Jezebel", The Oxford Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, OUP 2006

- ↑ 2Kings 9:30

- 1 2 3 4 Hackett, Jo Ann (2004). Metzger, Bruce M; Coogan, Michael D, eds. The Oxford Guide to People & Places of the Bible. Oxford University Press. pp. 150–151. ISBN 978-0195176100.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2001). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. Simon and Schuster. pp. 169–195. ISBN 978-0-684-86912-4.

- 1 2 3 "Jezebel", Jewish Encyclopedia

- 1 2 3 Bromiley, Geoffrey M., "Jezebel", International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1995, ISBN 9780802837820

- ↑ Brenner, Athalya. "Jezebel: Bible", Jewish Women's Archive

- ↑ Asimov, Isaac (1988). Asimov's Guide to the Bible: Two Volumes in One, the Old and New Testaments (reprint ed.). Wings. ISBN 978-0517345825.

- ↑ 2Kings 9:35-36

- ↑ IVP New Bible Commentary 21st Century Edition, pp 335

- ↑ "Ancient Seal Belonged To Queen Jezebel". Science Daily. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ↑ Liphshiz, Cnaan (11 October 2007). "The missing letter". Haaretz. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ↑ Korpel, Marjo C.A. "Fit for a Queen: Jezebel’s Royal Seal". Biblical Archaeology Society. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ↑

Cook, Stanley Arthur (1911). "Jezebel". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 411.

Cook, Stanley Arthur (1911). "Jezebel". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 411. - ↑ The New Testament, Book of Revelation., Ch. 2, vs. 20-23.

- ↑ "Meaning #2: "an impudent, shameless, or morally unrestrained woman"". Merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ↑ Pilgrim, David. "Jezebel Stereotype". Jim Crow Museum. Ferris State University. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ↑ "Jezebel". Cosmopolis. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ↑ Frankie Laine’s hits in the years 1947-1952.

- ↑ "Jezebel lyrics". Frankie Laine lyrics. Metro Lyrics. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ↑

- ↑ Leahey, Andrew. "Iron & Wine, "Jezebel"". americansongwriter.com. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ↑

- ↑ Asimov, Isaac, The Caves of Steel, Panther Books Ltd, 1958, 7th reprint 1973, p. 40-41.

- ↑ "At The Imperial: "Jezebel" Color Spectacle Stars Paulette Goddard In Title Role". The News and Eastern Townships Advocate. 14 January 1954. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ↑ Smith, Stephanie D.; Carmon, Irin (21 May 2007). "Memo Pad: Winners And Loosers… Going Home… Fool’s Gold…". Women's Wear Daily. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ↑

- ↑ "JEZEBEL The Untold Story of the Bible’s Harlot Queen by Lesley Hazleton". Kirkus reviews. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ↑ "Kelly Clarkson - Piece by Piece". Amazon. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ↑ "'Hannibal' Season 3 Episode 7, 'Digestivo'".

External links

-

Media related to Jezebel at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Jezebel at Wikimedia Commons

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||