History of the Jews in Gdańsk

The Jewish Community of Gdańsk (German: Danzig) dates back to at least the 15th century though for many centuries it was separated from the rest of the city. Under Polish rule, Jews acquired limited rights in the city in the 16th and 17th centuries and after the city's 1793 incorporation into Prussia the community largely assimilated to German culture. In the 1920s, during the period of the Free City of Danzig, the number of Jews increased significantly and the city acted as a transit point for Jews leaving Eastern Europe for the United States and Canada. Antisemitism existed among German nationalists and the persecution of Jews in the Free City intensified after the Nazis came to power in 1933. During World War II and the Holocaust the majority of the community either emigrated or were murdered. Since the fall of communism Jewish property has been returned to the community, and an annual festival, the Baltic Days of Jewish Culture, has taken place since 1999.

History

Early history

A Jewish community in Danzig proper did not exist until the 15th century.[1][2][3] The earliest records indicate that Jews were present in Gdańsk as early as 11th century.[4] In 1308 Gdańsk was taken over by the Teutonic Knights and a year later, the Grand Master of the Order, Siegfried von Feuchtwangen, forbid Jews to settle or remain in the city in an edict of non-toleration ("de non tolerandis Judaeis"). The knights weakened the restriction in early 15th century under pressure from the Grand Duke of Lithuania, Witold, and as a result a limited number of Jewish merchants from Lithuania and Volhynia were allowed to come to Danzig.[5] Around 1440 a "Judengasse" ("Jewish Lane", modern Spichrzowa) and around 1454 a Jewish settlement existed.[6]

After the end of the Thirteen Years' War the city returned to Poland and Jewish merchants came to trade from all over Poland and Lithuania. Many of them received special privileges from the King of Poland in regards to both the internal (along the Vistula river) as well as trans-Baltic trade. Others acted as agents of the szlachta (Polish nobility) in commercial matters.[5]

In 1476, on the initiative of the King of Poland, Casimir IV Jagiellon the city council allowed two Jewish merchants to have equal rights with other merchants.[6] Danzig's semi-autonomous status within the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth however allowed the city to refuse citizenship and trading rights to outsiders, thus the rights of Jews in the Kingdom did not apply in Danzig (similar restrictions also applied to Scots and Mennonites, many of whom also settled around the city).[1][5] On the insistence of local merchants, Jews had to move to the Schottland suburb outside of the city's boundary in 1520, subsequently Jews also settled in other places outside of the jurisdiction of the city.

The city burghers continued to curtail the rights of Jews in the city throughout the 16th century, particularly in regards to trade. This was opposed by the Jewish merchants through a boycott of the Danzig owned banking house in Kowno (which had to be closed down) and through the intercession of the Polish Kings on behalf of the Council of the Four Lands.[6]

In 1577, Danzig rebelled against the election of Stephen Báthory as King of Poland and an inconclusive siege of the city commenced. The negotiations that finally broke the stalemate included concessions by the Polish king in religious matters that also concerned Jews. Jewish religious services were not allowed in the city and in 1595 the city council again permitted sojourns only during the fair days. In the 1620s Jewish merchants were allowed to stay for the Domenic Fair and remain 4 days after its closure.[7]

At the beginning of the 17th century, almost half a thousand Jews lived in the city and, in 1620, King Zygmunt III Waza enforced an edict permitting the Jews to live within the city. A few years later, Jews were allowed to trade in grain and timber, first in one part of the city, then all of it.[6]

In 1752 a city ordinance regulated a tax of 12 Florin per month for a Jewish merchant, 8 Florin for an assistant and a 4 Florin for a servant.[1] 50 Jewish families received citizenship in 1773 and 160 Jews were allowed to reside in the city.[6]

Kingdom of Prussia

The situation changed with the First partition of Poland in 1772, when the suburbs became Prussian while the city of Danzig remained part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth until 1793. The 240 Jewish families (1,257 persons) of the Danzig suburbs received a General-Privilege in August 1773, which guaranteed their legal status. As Gershon C. Bacon states:[1]

This was the beginning of the association of Danzig Jewry with Germany, the German economy and German culture, which lasted until the dissolution of the community in the Nazi era.

Although the emancipation edict of 1812 improved the legal status of Jews in Prussia, anti-Jewish riots happened in 1819 and 1821 and the legal rights of Jews were often questioned by local officials.[1][6]

In the 19th century the communities of Altschottland (modern Stary Szkoty), Weinberg (modern Winnicka), Langfuhr (modern Wrzeszcz), Danzig-Breitgasse (modern Szeroka) and Danzig-Mattenbuden (modern Szopy) were still independent and elected their own officers, built synagogues, ran charitable institutions and chose their own rabbis. The Altschottland community started an initiative to unify the Jews of Danzig in 1878. A committee was established in 1880 and in February 1883 elections were held for a unified Kehilla board. In 1887 the new founded Synagogen-Gemeinde (Synagogue-kehilla) opened the Great Synagogue. Danzig Jewry at that time was a liberal, German-Jewish community and most Danzig Jews considered themselves "Germans of the Mosaic persuasion" and spoke German.[1][8]

Many Danzig Jews volunteered for military service in World War I,[3] about 95 of them died in service, a memorial plaque was later displayed in the Great Synagogue and shipped to New York's Jewish Museum in 1939.[1]

Free City of Danzig

After World War I Danzig became a Free City under the protection of the League of Nations. The number of Jews in Danzig grew rapidly as visa restrictions did not exist and many Jews from the areas attached to Poland after World War I, the Second Polish Republic and refugees of the Russian Civil War settled here or were awaiting visas for the US or Canada.[1]

Danzig Jewry, aided by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society took care for these refugees, which were housed in a transit camp in the port area.[6] Between 1920 and 1925 some 60,000 Jews passed through Danzig. The influence of Eastern European Jews, often sympathizing with Zionism, caused tensions within Synagogengemeinde Danzig. Besides the traditional Centralverein Danziger Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens (CV; Central Association of Danzig Citizens of Jewish Faith), led by Bernhard Kamnitzer, Jews from Russia and Poland founded the new "OSE" association, which also provided for charitable services such as a kindergarten, a public soup kitchen, a clothing store, occupational counselling, and a job service, as well as for a theatre for the people's edification and entertainment.

The OSE further ran a health centre in the former Friedländersche Schule on Jakobstor street #13. The native Jews tried to maintain their German-Liberal style community and their leadership made several attempts to restrict the participation of foreigners in the election of the Repräsentantenversammlung (legislative assembly of representatives) of Synagogengemeinde Danzig.[1] However, naturalised immigrants could vote so that also proponents of "Agudas Jisro'el" and "Misrachi", forming Jüdische Volkspartei (Yiddish: ייִדישע פֿאָלקספּאַרטײַ; Polish: fołkspartaj) ran for seats and eventually won some.

In 1920 the "Jung-Jüdischer Bund Danzig" (Young-Jewish Association Danzig) was founded, a newspaper, the Jüdisches Wochenblatt (Jewish weekly), was published from 1929 to 1938[6] as well as the Zionist Danziger Echo (until 1936).

A new synagogue was built on Mirchauer Weg in Langfuhr (Wrzeszcz) in 1927.[9] In 1931 the first world conference of the Betar was organized in Danzig.[10]

Persecution

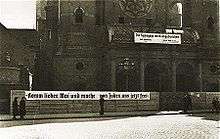

In the 1920s and early 1930s anti-Semitism grew[11] and the local Nazi party took power in the Volkstag (parliament) elections of 1933 and 1935. The Nazis took over the government in 1933 and as a result Jews were dismissed from public service and discriminated against in public life.[12][13] The presence of the League of Nations' High Commissioner however still guaranteed a minimum of legal certainty. In summer 1933 an "Association of Jewish Academics" was founded, which protested against the discrimination of Jews to the Senate and the League of Nations. Though the League declared several acts of the Nazi-government unconstitutional, this had no effect on the actual situation in the Free City. Following the example of the Jüdischer Kulturbund in Berlin a similar association existed since September 1933.[12]

On 23 October 1937 60 shops and several private residences were damaged in a Pogrom which followed a speech of the Nazi Party's Gauleiter of the city, Albert Forster.[14] This caused the flight of about the half of the Jewish community within a year.[6][12] In 1938 Forster initiated an official policy of repression against Jews; Jewish businesses were seized and handed over to Gentile Danzigers, Jews were forbidden to attend theaters, cinemas, public baths and swimming pools, or stay in hotels within the city, and, with the approval of the city's senate, barred from the medical, legal and notary professions. Jews from Zoppot (Sopot) were forced to leave that city within the Danzig state territory.[5] The Kristallnacht riots in Germany were followed by similar riots between 12 and 14 November 1938. The Synagogues in Langfuhr, Mattenbuden, and Zoppot were destroyed and the Great Synagogue was only saved because Jewish war veterans guarded the building.[1]

Following these riots the Nazi senate (government) introduced the racialist Nuremberg laws in November 1938[12][15] and the Jewish community decided to organize its emigration.[6][16] All property, including the Synagogues and cemeteries, was sold to finance the emigration of the Danzig Jewry.[2] The Great Synagogue on Reitbahn street was taken over by the municipal administration and torn down in May 1939. The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee paid up to $50,000[16] for the ceremonial objects, books, scrolls, tapestries, textiles and all kind of memorabilia, which arrived at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America on 26 July 1939. The extensive collection of Lesser Giełdziński was also shipped to New York, where it was placed at the Jewish museum.[2][5]

Holocaust

In early 1939 about 3,500 Jews, most of them Danzig citizens, were still living in the city. In March 1939 the first transport to Palestine departed[12] and by September 1939 barely 1,700, mostly elderly, Jews remained.

After the invasion of Poland by Wehrmacht and SS Heimwehr Danzig, followed by the German annexation of Danzig Free City, about 130 Jews were held in a "ghetto" in a building on Milchkannengasse street (today's ulica Stagiewna), and another group was imprisoned, along with the city's Poles, at the Victoriaschule, an old gymnasium building, where they were beaten and tortured. There were also camps at Westerplatte and Ohra (modern Orunia). Jews from Zoppot were executed in the Piaśnica forest murders. In 1940 another ghetto was created, which held about 600 individuals.[5]

The last group that managed to leave for Palestine departed in August 1940, with many of them facing the Patria disaster in Haifa port.[6][12] Of those who remained, 395 were deported during February and March 1941 to Warsaw Ghetto and 200 from the Jewish old age home were sent to Theresienstadt[6] and Auschwitz. Some were also taken out into the Baltic sea on barges and drowned.[5]

In the former territory of the Free City of Danzig Stutthof concentration camp was organized in September 1939, when first Jews arrived.[17] Tens of thousands of Jews (49 000) were sent there in 1944, many of them died.,[18][19]

At the end of World War II 22 Jewish partners of mixed marriages, who had remained in the city, survived.[6] About 350 individuals, from the areas surrounding the city, reported to the regional offices of the Central Committee of Polish Jews in the summer of 1945.[5]

Present day

Jewish life in Gdańsk began to revive as soon as the war was over. Jewish committees were organized within the city and region. In particular the Regional Jewish Committee (Okręgowy Komitet Żydowski) was composed of members of Ichud, Poale Zion and Poale Zion-Left members, as well as the Polish Communist Party. Members of the Bund however were excluded and not allowed to join by the Communist authorities. The religious organization Jewish Religious Organization of the (Pomeranian) Voivodeship (Wojewódzkie Żydowskie Zrzeszenie Religijne) was created in October 1945 and reacquired the synagogue in Wrzeszcz in the same year. However, the religious life of Gdańsk's Jews was slow during this time, partly because a good portion of those present in the city were non-religious and partly because of general anti-religious persecutions carried out by the Stalinist regime during the period 1947–53.[5]

During the March 1968 events, a major student and intellectual protests against the communist government of the People's Republic of Poland, the communist authorities instigated a wave of antisemitism as part of a "anti-Zionist" campaign. Jews of Gdańsk were also affected, as exemplified by the repressions directed at Wiktor Taubenfigiel, the director of the Gdańsk hospital.[5] Jakub Szadaj, a native of Gdańsk involved in Jewish cultural activities in the city and a prominent member of the democratic anti-communist opposition, was also arrested and sentenced to ten years in prison (later commuted to five). Szadaj was exonerated of all charges in post-Communist Poland in 1992.[20] An exhibit of photographs and documents entitled "Marzec '68" (March '68) covering the events was held in the Great Synagogue in 2010.[21] However the general subject of what impact the events of 1968 had on the Jewish community in Gdańsk has not yet been studied extensively.[5]

According to the In Your Pocket City Guide no member of the contemporary Jewish community is a descended of a prewar resident.[4] However, Jakub Szadaj, for example, is the son of Moses Szadaj, a citizen of the pre war Free City of Danzig.[20]

An annual festival, the Baltic Days of Jewish Culture (Bałtyckie Dni Kultury Żydowskiej), has been taking place in Gdańsk since 1999. It is organized by Social and Cultural Organization of Jews in Poland (Towarzystwo Społeczno-Kulturalne Żydów w Polsce) and Jakub Szadaj.[22][23]

In 2001 the only remaining pre-war synagogue, used as a warehouse for store furniture and as music school after World War II, was transferred to the Jewish community. Since September 2009 the complete "New Synagogue" serves for religious purposes again.[24] A photo exhibit "Żydzi gdańscy—Obrazy nieistniejącego świata" (Jews of Gdańsk—Images of a lost world) was held in the Opatów Palace in Oliwa in 2008. The exhibition included more than 200 photographs documenting the history of the Jewish community in the city from the end of the 19th century until 1968.[25]

The Independent Gmina of the Mosaic Faith (Niezależna Gmina Wyznania Mojżeszowego) represents about 100 Jews in the city,[26] a WUPJ affiliate. In addition to helping with the organization of the Baltic Days of Jewish Culture, it offers Hebrew lessons and keeps contact with the Beit Warszawa congregation in Warsaw.[27]

Demographics

| year | number of members[1][3] |

|---|---|

| 1765 | 1,098 (outside of the city's boundary) |

| 1816 | 3,798 |

| 1880 | 2,736 (2.4% of total population) |

| 1885 | 2,859 |

| 1895 | 2,367 |

| 1900 | 2,553 |

| 1905 | 2,546 |

| 1910 | 2,390 (1.4% of total population) |

| December 1910 | 2,717 |

| November 1923 | 7,282 (2,500 Danzig nationals, 4,782 non-citizens) |

| August 1924 | 9,239 |

| August 1929 | 10,448 |

| 1937 | 12,000 |

| 1939 | 1,666 |

Notable members

- Max Abraham, physicist

- Salomon Adler, one of the earliest Jewish painters in post-medieval Europe for which there is any documentation

- Ike Aronowicz, captain of the immigrant ship SS Exodus

- Aaron Bernstein, author, reformer and scientist

- Avraham Danzig, Rabbi, author Chayei Adam

- Samuel Echt, historian, teacher, community leader

- Alfred Flatow, gymnast, competed at the 1896 Summer Olympics in Athens.

- Levin Goldschmidt, jurist

- Salome Gluecksohn-Waelsch, geneticist, co-founder of the field of developmental genetics

- Theodor Hirsch, historian

- Maximilian Kaminsky, father of Mel Brooks

- Bernhard Kamnitzer, jurist, senator

- Isaac Landau, father of Moshe Landau

- Israel Lipschutz, rabbi, author of Tiferes Yisrael

- Hugo Münsterberg, psychologist, pioneer in applied psychology,

- Hugo Neumann (1882–1962), politician

- Meir Shamgar, President of the Israeli Supreme Court

- Rutka Laskier, Holocaust victim and diarist, called the Polish Anne Frank

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Danzig Jewry: A Short History by Gershon C. Bacon

- 1 2 3 Grass, Günther; Mann, Vivian B.; Gutmann, Joseph (1980). Danzig 1939, treasures of a destroyed community. New York: The Jewish Museum. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-8143-1662-7.

- 1 2 3 jewishgen.org

- 1 2 inyourpocket.com

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Żydzi na Pomorzu (Polish)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Gdansk at Jewish Virtual Library

- ↑ Kaplan, Yosef (2000). An alternative path to modernity. Brill. p. 93. ISBN 90-04-11742-3.

- ↑ Wolli Kaelter interview

- ↑ Schalom, Günther Grass, Die Tageszeitung, 7 October 2007

- ↑ Betar at Jewish Virtual Library

- ↑ Żydzi na terenie Wolnego Miasta Gdańska Grzegorz Berendt page 110, Gdańskie Tow. Nauk., Wydz. I Nauk Społecznych i Humanistycznych, 1997

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gippert, Wolfgang. "Die „Lösung der Judenfrage“ in der Freien Stadt Danzig" (in German). Zukunft braucht Erinnerung.

- ↑ Epstein, Catherine (2010). Model Nazi:Arthur Greiser and the Occupation of Western Poland. Oxford University Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-19-954641-1.

- ↑ Schenk, Dieter (2013). Danzig 1930 - 1945: Das Ende einer Freien Stadt (in German). Ch. Links. p. 70. ISBN 978-3-86153-737-3.

- ↑ Schwartze-Köhler, Hannelore (2009). "Die Blechtrommel" von Günter Grass:Bedeutung, Erzähltechnik und Zeitgeschichte (in German). Frank & Timme GmbH. p. 396. ISBN 978-3-86596-237-9.

- 1 2 Bauer, Yehuda (1981). American Jewry and the Holocaust. Wayne State University Press. p. 145. ISBN 0-8143-1672-7.

- ↑ Gelsenzentrum: Das Konzentrationslager Stutthof

- ↑ Jewishgen, German Jews at Stutthof Concentration Camp

- ↑ Stutthof Museum

- 1 2 (Polish) Wstrząs po latachNiezależna Gmina Wyznania Mojżeszowego w PR

- ↑ (Polish) Gdańsk. Wystawa "Marzec '68" w Nowej Synagodze

- ↑ Gdańsk.pl, official website of the city of Gdańsk, X Bałtyckie Dni Kultury Żydowskiej, last accessed August 9, 2010

- ↑ jewish.org.pl (Polish)

- ↑ Gdańsk shul back in Jewish hands Jerusalem Post 1 September 2009

- ↑ (Polish) Żydzi gdańscy - Obrazy nieistniejącego świata

- ↑ – Demografia

- ↑ interia.pl (Polish)

Bibliography

- Wolli Kaelter, From Danzig: An American Rabbi's Journey, Pangloss Press, 1997. ISBN 0-934710-36-8

- Mira Ryczke Kimmelman: Echoes from the Holocaust, a memoir ISBN 978-0-87049-956-2

- Samuel Echt, Die Geschichte der Juden in Danzig, (German)

- Erwin Lichtenstein, Die Juden der Freien Stadt Danzig unter der Herrschaft des Nationalsozialismus (German)

- Erwin Lichtenstein, Bericht an meine Familie,: ein Leben zwischen Danzig und Israel(German)