Peccary

| Peccaries Temporal range: 33.9–0 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Collared peccary, Pecari tajacu | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Suborder: | Suina |

| Family: | Tayassuidae Palmer, 1897 |

| Genera | |

| |

| |

| Range of the peccaries | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Dicotylidae | |

A peccary (also javelina or skunk pig) is a medium-sized hoofed mammal of the family Tayassuidae (New World pigs) in the suborder Suina along with the Old World pigs, Suidae. They are found throughout Central and South America and in the southwestern area of North America. Peccaries usually measure between 90 and 130 cm (3.0 and 4.3 ft) in length, and a full-grown adult usually weighs about 20 to 40 kg (44 to 88 lb).

Peccaries, which are native to the Americas, are often confused[1] with the pig family that originated in Afro-Eurasia, especially since some domestic pigs brought by European settlers have escaped over the years and now run wild as "razorback" hogs in many parts of the United States.[2]

In many countries, especially in the developing world, they are raised on farms as a source of food for local communities.[3]

Name

The word peccary is derived from the Carib word pakira or paquira.[4] In Brazilian Portuguese, a peccary is called pecari, porco-do-mato, queixada, or tajaçu, among other names; in Spanish, "javelina", jabalí, sajino, or pecarí; in French Guiana, pakira.

Characteristics

A peccary is a medium-sized animal, with a strong resemblance to a pig. Like a pig, it has a snout ending in a cartilaginous disc, and eyes that are small relative to its head. Also like a pig, it uses only the middle two digits for walking, although, unlike pigs, the other toes may be altogether absent. Its stomach is not ruminating, although it has three chambers, and is more complex than those of pigs.[5]

Peccaries are omnivores, and eat small animals, although their preferred foods consist of roots, grasses, seeds, fruit,[5] and cacti—particularly prickly pear.[6] Pigs and peccaries can be differentiated by the shape of the canine tooth, or tusk. In European pigs, the tusk is long and curves around on itself, whereas in peccaries, the tusk is short and straight. The jaws and tusks of peccaries are adapted for crushing hard seeds and slicing into plant roots,[5] and they also use their tusks for defending against predators. The dental formula for peccaries is: 2.1.3.33.1.3.3

By rubbing the tusks together, they can make a chattering noise that warns potential predators not to get too close. In recent years in northwestern Bolivia near Madidi National Park, large groups of peccaries have been reported to have seriously injured or killed people.[7]

Peccaries are social animals, and often form herds. Over 100 individuals have been recorded for a single herd of white-lipped peccaries, but collared and Chacoan peccaries usually form smaller groups. Such social behavior seems to have been the situation in extinct peccaries, as well. The recently discovered giant peccary (Pecari maximus) of Brazil appears to be less social, primarily living in pairs.[8]

Peccaries have scent glands below each eye and another on their backs, though these are believed to be rudimentary in P. maximus. They use the scent to mark herd territories, which range from 75 to 700 acres (2.8 km2). They also mark other herd members with these scent glands by rubbing one against another. The pungent odor allows peccaries to recognize other members of their herd, despite their myopic vision. The odor is strong enough to be picked up by humans, which earns the peccary the nickname of "skunk pig".

Species

Three (possibly four) living species of peccaries are found from the southwestern United States through Central America and into South America and Trinidad.

The collared peccary (Pecari tajacu) or "musk hog", referring to the animal's scent glands, occurs from the southwestern United States into South America and the island of Trinidad. They are found in all kinds of habitats, from arid scrublands to humid tropical rain forests. The collared peccary is well adapted to habitat disturbed by humans, merely requiring sufficient cover; they can be found in cities and agricultural land throughout their range. Notable populations exist in the suburbs of Phoenix and Tucson, Arizona, where they feed on ornamental plants and other cultivated vegetation.[9][10] Collared peccaries are generally found in bands of eight to 15 animals of various ages. They defend themselves if they feel threatened, but otherwise tend to ignore humans. They defend themselves with their long tusks, which sharpen themselves whenever the mouth opens or closes.

A second species, the white-lipped peccary (Tayassu pecari), is mainly found in rainforests of Central and South America, but also known from a wide range of other habitats such as dry forests, grasslands, mangrove, cerrado, and dry xerophytic areas.[11]

The third species, the Chacoan peccary (Catagonus wagneri), is the closest living relative to the extinct Platygonus pearcei. It is found in the dry shrub habitat or Chaco of Paraguay, Bolivia, and Argentina. The Chacoan peccary has the unusual distinction of having been first described based on fossils and was originally thought to be only an extinct species. In 1975, the animal was discovered to still be alive and well in the Chaco region of Paraguay. The species was well known to the native people.

A fourth as yet unconfirmed species, the giant peccary (Pecari maximus), was described from the Brazilian Amazon and north Bolivia[12] by Dutch biologist Marc van Roosmalen. Though relatively recently discovered, it has been known to the local Tupi people as caitetu munde, which means "great peccary which lives in pairs".[13][14] Thought to be the largest extant peccary, it can grow to 1.2 m (3.9 ft) in length. Its pelage is completely dark gray, with no collars whatsoever. Unlike other peccaries, it lives in pairs, or with one or two offspring. However, the scientific evidence for considering it as a species separate from the collared peccary has later been questioned,[15][16] leading the IUCN to treat it as a synonym.[17]

Evolution

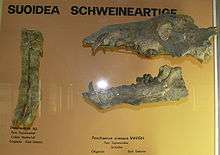

Peccaries first appeared in the fossil records of the Late Eocene or Early Oligocene periods in Europe. Fossils have later been found in all continents except Australia and Antarctica. It became extinct in the Old World sometime after the Miocene period. Extinct genera include Macrogenis from the Miocene, and Floridachoerus.

Although they are common in South America today, peccaries did not reach that continent until about three million years ago during the Great American Interchange, when the Isthmus of Panama formed, connecting North America and South America. At that time, many North American animals—including peccaries, llamas and tapirs—entered South America, while some South American species, such as the ground sloths, and opossums, migrated north.[18]

References

- ↑ George Oxford Miller (October 1988). A field guide to wildlife in Texas and the Southwest. Texas Monthly Press. ISBN 978-0-87719-126-1. Retrieved 26 December 2011. "many people confuse them with domestic pigs gone wild"

- ↑ Susan L. Woodward; Joyce A. Quinn (30 September 2011). Encyclopedia of Invasive Species: From Africanized Honey Bees to Zebra Mussels. ABC-CLIO. pp. 277–. ISBN 978-0-313-38220-8. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ↑ Commercial farming of collared peccary: A Large-scale commercial farming of collared peccary (Tayassu tajacu) in North-Eastern Brazil. Pigtrop.cirad.fr (2007-04-30). Retrieved on 2012-12-18.

- ↑ "Peccary". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved March 26, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Castellanos, Hernan (1984). Macdonald, D., ed. The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. pp. 504–505. ISBN 0-87196-871-1.

- ↑ Sowls, Lyle K. (1997). Javelinas and Other Peccaries: Their Biology, Management, and Use (2 ed.). Texas A&M University Press. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-0-89096-717-1.

- ↑ Madidi Diary – Joel Sartore. Sartorestock.com. Retrieved on 2012-12-18.

- ↑ Roosmalen, M.G.M.; Frenz, L.; Hooft, W.F. van; Iongh, H.H. de; Leirs, H. (2007). "A New Species of Living Peccary (Mammalia: Tayassuidae) from the Brazilian Amazon". Bonner zoologische Beitrage 55 (2): 105–112.

- ↑ Friederici, Peter (August–September 1998). "Winners and Losers". National Wildlife Magazine (National Wildlife Federation) 36 (5).

- ↑ Sowls, Lyle K. (1997). Javelinas and Other Peccaries: Their Biology, Management, and Use (2 ed.). Texas A&M University Press. pp. 67–68. ISBN 978-0-89096-717-1.

- ↑ Keuroghlian, A., Desbiez, A., Reyna-Hurtado, R., Altrichter, M., Beck, H., Taber, A. & Fragoso, J.M.V. (2013). "{{{title}}}". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.3. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ↑ Moravec, J., & Böhme, W. (2009). Second Find of the Recently Discovered Amazonian Giant Peccary, Pecari maximus (Mammalia: Tayassuidae) van Roosmalen et al., 2007: First Record from Bolivia. Bonner zoologische Beiträge 56(1-2): 49-54.

- ↑ Lloyd, Robin (2007-11-02). Big Pig-Like Beast Discovered. livescience.com

- ↑ Giant wild pig found in Brazil. The Guardian (2007-11-05). Retrieved on 2012-12-18.

- ↑ Gongora, J., Taber, A., Keuroghlian, A., Altrichter, M., Bodmer, R.E., Mayor, P., Moran, C., Damayanti, C.S., González S. (2007). Re-examining the evidence for a 'new' peccary species, 'Pecari maximus', from the Brazilian Amazon. Newsletter of the Pigs, Peccaries, and Hippos Specialist Group of the IUCN/SSC. 7(2): 19–26.

- ↑ Gongora, J., Biondo, C., Cooper, J.D., Taber, A., Keuroghlian, A., Altrichter, M., Ferreira do Nascimento, F., Chong, A.Y., Miyaki, C.Y., Bodmer, R., Mayor, P. and González, S. (2011). Revisiting the species status of Pecari maximus van Roosmalen et al., 2007 (Mammalia) from the Brazilian Amazon. Bonn Zoological Bulletin 60(1): 95-101.

- ↑ Gongora, J., Reyna-Hurtado, R., Beck, H., Taber, A., Altrichter, M. & Keuroghlian, A. (2011). "Pecari tajacu". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.3. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ↑ McDonald, Greg (1999-03-27) Pearce's Peccary – Platygonus Pearcei. Hagerman Fossil Beds' CRITTER CORNER.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tayassuidae. |