Japanese folktales

Japanese folktales are the folktales of Japan. In commonplace usage, it signifies a certain set of well-known classic tales, with a vague distinction of whether they fit the rigorous definition of folktale or not.

The admixed imposters are literate written pieces, dating back to the Muromachi period (14th-16th centuries) or even earlier times in the Middle Ages. These would not normally qualify as "folktales" (i.e., pieces collected from oral tradition among the populace).

In a more stringent sense, "Japanese folktales" refer to orally transmitted folk narrative. Systematic collection of specimens was pioneered by folklorist Kunio Yanagita. Yanagita disliked the word minwa (民話), a coined term directly translated from "folktale" (Yanagita stated that the term was not familiar to actual old folk he collected folktales from, and was not willing to "go along" with the conventions of other countries[1]). He therefore proposed the use of the term mukashibanashi (昔話 "tales of long ago") to apply to all creative types of folktales (i.e., those that are not "legendary" types which are more of a reportage).[2]

Overview

A representative sampling of Japanese folklore would definitely include the quintessential Momotarō (Peach Boy), and perhaps other folktales listed among the so-called "five great fairy tales" (五大昔話 Go-dai Mukashi banashi):[3] the battle between The Crab and the Monkey, Shita-kiri Suzume (Tongue-cut sparrow), Hanasaka Jiisan (Flower-blooming old man), and Kachi-kachi Yama.

These stories just named are considered genuine folktales, having received those auspices by folklorist Kunio Yanagita.[4] During the Edo Period these tales had been adapted by professional writers and woodblock-printed in a form a called kusazōshi (cf.chapbooks), but a number of local variant versions of the tales have been collected in the field as well.

As aforestated, non-genuine folktales are those already committed to writing long ago, the earliest being the tale of Princess Kaguya (or The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter), an example of monogatari type of romance dated to as early as the 10th century,[5] though extant manuscripts are much later. The text gives reference, for example, to the flame-proof "fire rat (火鼠 Hinezumi) (or salamander)'s fur robe" (perhaps familiar to watchers of the anime InuYasha as the vestment of the title character), which attests to considerable degree of book-knowledge and learning by its author.

Other examples of pseudo-folktales which have been composed in the Middle Ages are the Uji Shūi Monogatari (13th century) that includes the nucleus of classics as (Kobutori Jīsan - the old man with the hump on his cheek, and Straw Millionaire). This and the Konjaku Monogatarishū (12th century) also contains a number of type of tales designated setsuwa, a generic term for narratives of various nature, anything from moralizing to comical. Both works, it might be noted, are divided into parts containing tales from India, tales from China, and tales from Japan. In the Konjaku Monogatarishū can be seen the early developments of the Kintarō legend, familiar in folktale-type form.

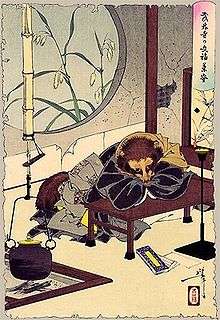

The Japanese word used to correspond to "folktale" has undergone development over the years. From the Edo Period, the term used was otokibanashi (お伽話), i.e., tales told by the otogii-shū who were professional storytellers hired to entertain the daimyo lord at the bedside.[6] That term continued to be in currency through the Meiji era (late 19th century), when imported terms such as minwa began usage.[6] In the Taisho era, the word dōwa (lit. "children's story" but was a translated coinage for fairy tales or märchen) was used.[6] Then Yanagita popularized the use of mukashi-banashi "tales of long ago", as mentioned before.

Although some Japanese ghost stories or kaidan such as the story of the Yuki-onna ("snow woman") might be considered examples of folktales, but even though some overlaps may exist, they are usually treated as another genre. The familiar forms of stories are embellished works of literature by gesaku writers, or retooled for the kabuki theater performance, in the case of the bakeneko or monstrous cat. The famous collection Kwaidan by Lafcadio Hearn also consists of original retellings. Yanagita published a collection 'Legends of Tohno (遠野物語 Tohno Monogatari)' (1910) which featured a number of fanatastical yokai creatures such as Zashiki-warashi and kappa.

In the middle years of the 20th century storytellers would often travel from town to town telling these stories with special paper illustrations called kamishibai.

List of tales

Below is a list of well-known Japanese folktales:

| No. | Name | Portrait | Note | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hero/heroine type | |||||

| 1 | Chikarataro | ||||

| 2 | Issun-boshi | |

the One-inch Boy | ||

| 3 | Kintaro |  |

the superhuman Golden Boy, based on folk hero Sakata no Kintoki | ||

| 4 | Momotaro |  |

the oni-slaying Peach Boy | ||

| 5 | The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter |  |

about a mysterious girl called Kaguya-hime who is said to be from the capital of the moon | ||

| grateful creature motif | |||||

| 6 | Bunbuku Chagama |  |

the story of a teakettle which is actually a shape-changing tanuki | ||

| 7 | Hanasaka Jiisan | the story of the old man that made the flowers bloom | |||

| 8 | Kasa jizo | a Jizo statue given a straw hat and is grateful | |||

| 9 | Omusubi kororin | a Jizo statue given a straw hat and is grateful | |||

| 10 | Shita-kiri Suzume | |

the story of the tongue-cut sparrow | ||

| 11 | Yuko-Chan and the Daruma Doll | the story about the adventures of a blind Japanese girl who saves her village; written by Sunny Seki | |||

| 12 | Urashima Taro |  |

who rescued a turtle and visited the bottom of the sea | ||

| 13 | My Lord Bag of Rice |  |

|||

| good fortune motif | |||||

| 14 | Kobutori Jīsan |  |

a man with a large wen (tumor, kobu) on his cheek, and how he loses it | ||

| 15 | Straw Millionaire | (warashibe choja (??????)) | |||

| punishment motif | |||||

| 16 | The Crab and the Monkey | |

(saru kani gassen (????)) | ||

| 17 | Kachi-kachi Yama |  |

rabbit punishes tanuki | ||

Animals in folklore

Tongue-cut sparrow: A washer woman cut off the tongue of a sparrow that was pecking at her rice starch. The sparrow had been fed regularly by the washer woman’s neighbors, so when the sparrow didn’t come, they went in the woods to search for it. They found it, and after a feast and some dancing (which the sparrow prepared), the neighbors were given the choice between two boxes; one large and one small. The neighbors picked the small box, and it was filled with riches. The washer woman saw these riches and heard where they came from, so she went to the sparrow. She too was entertained and given the choice between two boxes. The washer woman picked the largest box and instead of gaining riches, she was devoured by devils.[7]

Mandarin Ducks: A man kills a drake mandarin duck for food. That night he had a dream that a woman was accusing him of murdering her husband, and then told him to return to the lake. The man does this, and a female mandarin walks up to him and tears its chest open.[7]

Tanuki and Rabbit: A man catches a tanuki and tells his wife to cook it in a stew. The tanuki begs the wife not to cook him and promises to help with the cooking if he is spared. The wife agrees and unties him. The tanuki then transforms into her and kills her, then cooks her in a stew. Disguised as the man’s wife, the tanuki feeds him his wife. Once he is done, the tanuki transforms back to his original form and teases the man for eating his wife. A rabbit that was friends with the family was furious, so he had the tanuki carry sticks and, while he wasn’t looking, set these sticks on fire. Then the rabbit treated the burn with hot pepper paste. Finally the rabbit convinced the tanuki to build a boat of clay, and the rabbit followed in a sturdy boat. The clay boat began to sink, so the tanuki tried to escape, but then the rabbit hit him in the head with an oar, knocking him out and making him drown.[7]

Badger and Fox cub: A badger, vixen, and the vixen’s cub lived in a forest that was running out of food, so they came up with the plan of one of them pretending to be dead, the other disguising as a merchant, and the “merchant” selling the “dead” animal to a human. Then they would have money to buy food. The vixen pretended to be dead while the badger was the merchant. While the transaction was happening however, the badger told the human that the vixen wasn’t actually dead, so the human killed her. This infuriated the cub, so he proposed a competition. They would both disguise as humans and go into the village at different times. Whoever guessed what “human” was the other first, wins. The cub walked towards the village first, but he hid behind a tree. The badger went into the village, and accused the governor of being the fox, so the bodyguards of the governor beheaded him.[7]

Theorized influences

The folklore of Japan has been influenced by foreign literature as well as the kind of spirit worship prevalent all throughout prehistoric Asia.

The monkey stories of Japanese folklore have been influenced both by the Sanskrit epic Ramayana and the Chinese classic Journey to the West.[8] The stories mentioned in the Buddhist Jataka tales appear in a modified form throughout the Japanese collection of popular stories.[9][10]

Some stories of ancient India were influential in shaping Japanese stories by providing them with materials. Indian materials were greatly modified and adapted in such a way as would appeal to the sensibilities of common people of Japan in general, transmitted through China and Korea.[11][12]

See also

- Gesaku

- Tale of the Gallant Jiraiya Jiraiya Goketsu Monogatari

- Kaidan

- Banchō Sarayashiki, the ghost story of Okiku and the Nine Plates.

- Yotsuya Kaidan, the ghost story of Oiwa.

- Yukionna, the snow woman.

- Legends

- Hagoromo legend, related to Hagoromo (play)

- Kiyohime legend; passionate for a priest, she turned into a dragon.

- Tamamo-no-Mae, a vixen-type yōkai monster, masquerading as a woman.

- Tokoyo, a girl who reclaimed the honour of her samurai father.

- Ushiwakamaru, about Yoshitsune's youth and training with the tengu of Kurama.

- Mythology

- Luck of the Sea and Luck of the Mountains

- Setsuwa

- Urban Legends

References

- ↑ Yanagita, "Preface to the 1960 edition", appended to Nihon no mukashibanashi (Folk tales of Japan), Shinchosha, 1983, p.175.

- ↑ Heibonsha 1969, encyclopedia, vol.21, 492

- ↑ Asakura, Haruhiko(朝倉治彦) (1963). 神話伝説事典 (snippet). 東京堂出版. ISBN 978-4-490-10033-4.,p.198. quote:"ごだいおとぎぱなし(五大御伽話)。五大昔話ともいう。桃太郎、猿蟹合戦、舌切雀、花咲爺、かちかち山の五話"

- ↑ Yanagita, Kunio(柳田國男) (1998). Collected Works (柳田國男全集) (snippet) 6. Tsukuma Shobo., p.253, says calling them otogibanashi (see below) is a misnomer, since they are mukashi banashi (Yanagita's preferred term for folktales orally transmitted)

- ↑ Dickins, F. Victor (Frederick Victor), 1838-1915 (1888). The Old Bamboo-Hewer's Story (Taketori no okina no monogatari): The earliest of the Japanese romances, written in the 10th century (google). Trübner.

- 1 2 3 Heibonsha 1969, encyclopedia, vol.21, 499-504, on mukashibanashi by Shizuka Yamamuro and Taizo Tanaka

- 1 2 3 4 Japanese Mythology: Library of the World's Myths and Legends, by Juliet Piggott

- ↑ On the Road to Baghdad Or Traveling Biculturalism: Theorizing a Bicultural Approach to... By Gonul Pultar, ed., Gönül Pultar. Published 2005. New Academia Publishing, LLC. ISBN 0-9767042-1-8. Page 193

- ↑ The Hindu World By Sushil Mittal. Published 2004. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-21527-7. pp93

- ↑ Discovering the Arts of Japan: A Historical Overview By Tsuneko S. Sadao, Stephanie Wada. Published 2003. Kodansha International. ISBN 4-7700-2939-X. pp41

- ↑ Miraculous Stories from the Japanese Buddhist Tradition: The Nihon Ryōiki of the Monk Kyōkai By Kyōkai. Published 1997. Routledge. ISBN 0-7007-0449-3

- ↑ The Sanskrit Epics By John L Brockington. Published 1998. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-02642-8. pp514

- Heibonsha (1969) [1968]. 世界百科事典(Sekai hyakka jiten) 15. pp. 804–6., Article under densetsu (伝説), by Keigo Seki (ja:関敬吾)

- Heibonsha (1969) [1968]. 世界百科事典(Sekai hyakka jiten) 21. p. 492., Article under minwa (民話), by Katsumi Masuda (ja:益田勝実)

- Heibonsha (1969) [1968]. 世界百科事典(Sekai hyakka jiten) 21. pp. 499–504., Article under mukashibanashi (昔話), by Shizuka Yamamuro (ja:山室静) and Taizo Tanaka (ja:田中泰三)

- Gordon Smith, Richard, 1858-1918. (1908). Ancient Tales and Folklore of Japan (Forgotten Books). London: A. & C. Black.

- Rasch, Carsten: TALES OF OLD JAPAN FAIRY TALE - FOLKLORE - GHOST STORIES - MYTHOLOGY: INTRODUCTION IN THE JAPANESE LITERATURE OF THE GENRE OF FAIRY TALES - FOLKLORE - GHOST STORIES AND MYTHOLOGY, Hamburg 2015.