Japanese aircraft carrier Zuihō

Zuihō in 1940 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Takasaki |

| Namesake: | Auspicious Phoenix or Fortunate Phoenix |

| Builder: | Yokosuka Naval Arsenal |

| Laid down: | 20 June 1935 |

| Launched: | 19 June 1936 |

| Commissioned: | 27 December 1940 |

| Renamed: | Zuihō |

| Fate: | Sunk by air attack during the Battle of Cape Engaño, 25 October 1944 |

| General characteristics (as converted) | |

| Class & type: | Zuihō-class aircraft carrier |

| Displacement: | 11,443 tonnes (11,262 long tons) (standard) |

| Length: | 205.49 m (674 ft 2 in) |

| Beam: | 18.19 m (59 ft 8 in) |

| Draft: | 6.58 m (21 ft 7 in) |

| Installed power: | 52,000 shp (39,000 kW) |

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph) |

| Range: | 7,800 nmi (14,400 km; 9,000 mi) at 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) |

| Complement: | 785 |

| Armament: |

|

| Aircraft carried: | 30 |

Zuihō (瑞鳳, "Auspicious Phoenix" or "Fortunate Phoenix") was a light aircraft carrier of the Imperial Japanese Navy. Originally laid down as the submarine support ship Takasaki, she was renamed and converted while under construction into an aircraft carrier. The ship was completed during the first year of World War II and participated in many operations. Zuihō played a secondary role in the Battle of Midway in mid-1942 and did not engage any American aircraft or ships during the battle. The ship participated in the Guadalcanal Campaign during the rest of 1942. She was lightly damaged during the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands during this campaign and covered the evacuation of Japanese forces from the island in early 1943 after repairs.

Afterwards, her aircraft were disembarked several times in mid- to late-1943 and used from land bases in a number of battles in the South West Pacific. Zuihō participated in the Philippine Sea and Leyte Gulf battles in mid-1944. In this last battle, Zuihō mainly served as a decoy for the main striking forces and she was finally sunk by American aircraft fulfilling her task. In between engagements, the ship served as a ferry carrier and a training ship.

Design and conversion

The submarine support ship Takasaki was laid down on 20 June 1935 at the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal and was designed to be converted to either a fleet oiler or a light aircraft carrier as needed. She was launched on 19 June 1936 and began a lengthy conversion into a carrier while fitting-out. The ship was renamed Zuihō during the process which was not completed until 27 December 1940 when she was commissioned.[1]

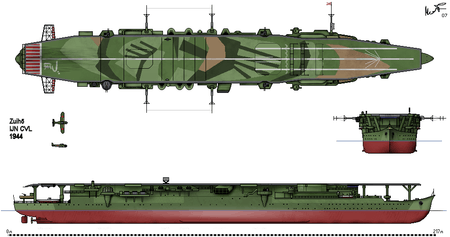

After her conversion, Zuihō had a length of 205.49 meters (674 ft 2 in) overall. She had a beam of 18.19 meters (59 ft 8 in) and a draft of 6.58 meters (21 ft 7 in). She displaced 11,443 tonnes (11,262 long tons) at standard load. As part of her conversion, her original diesel engines, which had given her a top speed of 29 knots (54 km/h; 33 mph), were replaced by a pair of destroyer-type geared steam turbine sets with a total of 52,000 shaft horsepower (39,000 kW), each driving one propeller. Steam was provided by four water-tube boilers and Zuihō now had a maximum speed of 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph). The boilers exhausted through a single downturned starboard funnel and she carried 2,600 tonnes (2,600 long tons) of fuel oil that gave her a range of 7,800 nautical miles (14,400 km; 9,000 mi) at a speed of 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph).[2] Her crew numbered 785 officers and men.[1]

Zuihō's flight deck was 179.98 meters (590 ft 6 in) long and had a maximum width of 23.01 meters (75 ft 6 in). The ship was designed with a single hangar 124.00 meters (406 ft 10 in) long and 17.98 meters (59 ft 0 in) wide.[3] The hangar was served by two octagonal centerline aircraft elevators. The forward elevator was 13.01 by 11.99 meters (42.67 by 39.33 ft) in size and the smaller rear elevator measured 11.99 by 10.79 meters (39.33 by 35.4 ft). She had arresting gear with six cables, but she was not fitted with an aircraft catapult. Zuihō was a flush-deck design and lacked an island superstructure. She was designed to operate 30 aircraft.[1]

The ship's primary armament consisted of eight 40-caliber 12.7 cm Type 89 anti-aircraft (AA) guns in twin mounts on sponsons along the sides of the hull. Zuihō was also initially equipped with four twin 25 mm Type 96 light AA guns, also in sponsons along the sides of the hull. In 1943, her light AA armament was increased to 48 twenty-five mm guns. The following year, an additional twenty 25 mm guns were added in addition to six 28-round AA rocket launchers.[4]

Service

After commissioning, Zuihō remained in Japanese waters until late 1941. Captain Sueo Ōbayashi assumed command on 20 September and Zuihō became flagship of the Third Carrier Division ten days later. On 13 October she was briefly assigned to the 11th Air Fleet in Formosa and arrived in Takao the following day. The ship returned to Japan in early November and was given a brief refit later in the month. Together with the carrier Hōshō and six battleships, Zuihō covered the return of the ships of the 1st Air Fleet as they returned from the Attack on Pearl Harbor in mid-December.[5]

On February 1942, the ship ferried Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters to Davao City, Philippines. Zuihō remained in Japanese waters until June when she participated in the Battle of Midway.[5] She led the Support Fleet and did not engage American carriers directly. Her aircraft complement consisted of six Mitsubishi A5M "Claude" and six Mitsubishi A6M2 "Zero" fighters, and twelve Nakajima B5N2 "Kate" torpedo bombers.[6] After a brief refit in July–August, the ship was assigned to First Carrier Division with Shōkaku and Zuikaku on 12 August.[5]

The division sailed to Truk on 1 October to support Japanese forces in the Guadalcanal Campaign and left Truk on 11 October[5] based on the promise of the Japanese Army to capture Henderson Field on Guadalcanal. At this time, Zuihō carried 18 A6Ms and 6 B5Ns. The Japanese and American carrier forces discovered each other in the early morning of 26 October during the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands and each side launched air strikes. The aircraft passed each other en route and 9 of Zuihō's Zeros attacked the aircraft launched by the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise. They shot down 3 each Grumman F4F Wildcat fighters and Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bombers and damaged one more of each type while losing four of their own. Two of Enterprise's Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers hit Zuihō with 500-pound (230 kg) bombs and damaged her flight deck enough that she could not conduct flight operations although she was not seriously damaged otherwise.[7] Together with the damaged Shōkaku, the ship withdrew from the battle and reached Truk two days later. After temporary repairs, the two carriers returned to Japan in early November and Zuihō's repairs were completed on 16 December. In the meantime, Captain Bunjiro Yamaguchi assumed command.[5]

The ship left Kure on 17 January 1943 and sailed for Truk with a load of aircraft. Upon arrival she was assigned to the Second Carrier Division to provide cover for the evacuation of Guadalcanal, along with Jun'yō and Zuikaku, later in the month and in early February. Zuihō's fighters were transferred to Wewak, New Guinea in mid-February and then to Kavieng in early March. They were transferred to Rabaul on mid-March to participate in Operation I-Go, a land-based aerial offensive against Allied bases in the Solomon Islands and New Guinea. The fighters returned to Truk on 18 March after claiming 18 Allied aircraft shot down.[8] Zuihō arrived at Sasebo on 9 May and received a brief refit in mid-June. She returned to Truk on 15 July and remained in the area until 5 November when she returned to Yokosuka.[5] Her air group, 18 Zeros and eight D3As, was briefly deployed to Kavieng in late August – early September before returning to Truk.[9] By this time, Zuihō was assigned to the First Carrier Division with Shōkaku and Zuikaku and they sailed for Eniwetok Atoll on 18 September for training and to be in position to intercept any attacks by American carriers in the vicinity of Wake Island and the Marshall Islands area. That day the American carriers raided the Gilbert Islands and were gone by the time the Japanese reached Eniwetok on 20 September. Japanese intelligence reports pointed to another American attack in the Wake-Marshall Islands area in mid-October and Admiral Mineichi Koga sortied the Combined Fleet, including the First Carrier Division, on 17 October. They arrived at Eniwetok two days later and waited for reports of American activity until 23 October. They then sailed for Wake Island and then returned to Truk on 26 October without encountering any American ships.[10]

Zuihō's air group was transferred to Rabaul at the beginning of November, just in time to participate in the raid on Rabaul a few days later. The fighters claimed to have shot down 25 American aircraft at the cost of 8 of their own; the survivors flew back to Truk where they remained.[9] On 30 November, Zuihō, together with the escort carriers Chūyō and Unyō, departed Truk for Japan, escorted by four destroyers. The Americans had cracked the Japanese naval codes and positioned several submarines along their route to Yokosuka. Skate unsuccessfully attacked Zuihō on 30 November, while Sailfish torpedoed and sank Chūyō five days later with heavy loss of life.[11] From December to May 1944, Zuihō ferried aircraft and supplies to Truk and Guam although she was reassigned to the Third Carrier Division on 29 January,[5] together with the converted carriers Chitose and Chiyoda. Each of the three carriers was intended to be equipped with 21 fighters and 9 torpedo bombers, but this plan was changed on 15 February to a consolidated air group, the 653rd, that controlled the aircraft of all three carriers.[9] While fully equipped by May with 18 Zero fighters, 45 Zero fighter-bombers, 18 B5Ns, and 9 Nakajima B6N "Jill" torpedo bombers,[12] the air group's pilots were largely drawn from the two most recent classes and lacked experience.[13] The ship sailed for Tawi-Tawi on 11 May in the Philippines. The new base was closer to the oil wells in Borneo on which the Navy relied and also to the Palau and western Caroline Islands where the Japanese expected the next American attack. However, the location lacked an airfield on which to train the green pilots and American submarines were very active in the vicinity which restricted the ships to the anchorage.[14]

Battle of the Philippine Sea

The 1st Mobile Fleet was en route to Guimares Island in the central Philippines on 13 June, where they intended to practice carrier operations in an area better protected from submarines, when Vice Admiral Jisaburō Ozawa learned of the American attack on the Mariana Islands the previous day. Upon reaching Guimares, the fleet refueled and sortied into the Philippine Sea where they spotted Task Force 58 on 18 June. The Americans failed to locate Ozawa's ships that day and the Japanese turned south to maintain a constant distance between them and the American carriers as Ozawa had decided on launching his air strikes early the following morning. He had deployed his forces in a "T"- shaped formation with the 3rd Carrier Division at the end of the stem, 115 nautical miles (213 km; 132 mi) ahead of the 1st and 2nd Carrier Divisions that formed the crossbar of the "T". Zuihō and her consorts were intended to draw the attentions of the Americans while the other carriers conducted their air strikes without disruption. Sixteen Aichi E13A floatplanes were launched by the heavy cruisers accompanying the carriers at 04:30 to search for the Americans; the three carriers launched a follow up wave of 13 B5Ns at 05:20. The first wave spotted one group of four carriers from Task Force 58 at 07:34 and the Japanese carriers launched their aircraft an hour later. This consisted of 43 Zero fighter-bombers and 7 B6Ns, escorted by 14 A6M5 fighters; the carriers retained only 3 fighters, 2 fighter-bombers, 2 B6Ns and 2 B5Ns for self-defense and later searches. While the air strike was still forming up, the second wave of searchers located Task Force 58's battleships and the air strike was diverted to attack them. The Americans detected the incoming Japanese aircraft at 09:59 and had a total of 199 Grumman F6F Hellcat fighters in the air by the time the Japanese aircraft were in range of the American ships. The defending fighters decimated the Japanese aircraft and only 21 survived. The only damage inflicted was from one A6M2 that hit the battleship South Dakota in her superstructure with a single 250-kilogram (550 lb) bomb that wounded 50 crewmen, but did little other damage. Only 3 Hellcats were lost in the affair, one to a B6N, although the Japanese claimed four victories. Some of the surviving Japanese aircraft landed at Guam while others, including the five surviving B6Ns, returned to their carriers where they claimed one carrier definitely damaged and another probably hit.[15]

At dusk, the Japanese turned away to the northwest to regroup and to refuel and the Americans turned west to close the distance. Both sides launched aircraft the next day to locate each other; Zuihō launched three aircraft at 12:00 to search east of the fleet, but they did not discover the Americans. The Americans discovered the retiring Japanese fleet during the afternoon and Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher ordered an air strike launched. While they sank the carrier Hiyō and damaged two others, Zuihō was not attacked and successfully disengaged that evening.[16] By the end of the battle, Air Group 653 was reduced to 2 Zero fighters, 3 Zero fighter-bombers and 6 torpedo bombers.[17] After reaching Japan on 1 July, the ship remained in Japanese waters until October,[5] training replacements for her air group.[18]

Battle of Leyte Gulf

After the Battle of the Philippine Sea, the commander of the Combined Fleet, Admiral Soemu Toyoda, prepared four "victory" plans: Shō-Gō 1 (捷1号作戦 Shō ichigō sakusen) was a major naval operation in the Philippines, while Shō-Gō 2 was intended to defend Formosa, the Ryukyu Islands and southern Kyushu. Shō-Gō 3 and Shō-Gō 4 were responses to attacks on Kyushu-Shikoku-Honshu and Hokkaido respectively.[19] He activated Shō-Gō 2 after the Americans attacked the Philippines, Formosa and the Ryukyu Islands beginning on 10 October.[20] This required the transfer of most of Air Group 652 to Formosa and Luzon to attack the American forces, with only a few aircraft retained for carrier operations.[18] Most of these aircraft were lost for little gain as the Americans suppressed Japanese defenses in the Philippines, preparatory to the actual invasion.[21]

On 17 October, Admiral Toyoda alerted the fleet that Shō-Gō 1 was imminent and activated the plan the following day after receiving reports of the landings on Leyte. Zuihō's role in Shō-Gō 1, together with Chiyoda, Chitose and Zuikaku and the rest of the Main Body of the 1st Mobile Fleet, approaching Leyte Gulf from the north, was to serve as decoys to attract attention away from the two other forces approaching from the south and west. All forces were to converge on Leyte Gulf on 25 October and the Main Body left Japan on 20 October. As decoys, the carriers were only provided with a total of 116 aircraft: 52 Zero fighters, 28 Zero fighter-bombers, 7 Yokosuka D4Y "Judy" dive bombers, 26 B6N and 4 B5N torpedo bombers. By the morning of 24 October, the Main Body was within range of the northernmost American carriers of Task Force 38 and Admiral Ozawa ordered an air strike launched to attract the attention of the Americans. This accomplished little else as the Japanese aircraft failed to penetrate past the defending fighters; the survivors landed at airfields on Luzon. The Americans were preoccupied dealing with the other Japanese naval forces and defending themselves from air attacks launched from Luzon and Leyte and could not spare any aircraft to search for the Japanese carriers until the afternoon. They finally found them at 16:05, but Admiral William Halsey, Jr., commander of Task Force 38, decided that it was too late in the day to mount an effective strike. He did, however, turn all of his ships north to position himself for a dawn attack on the Japanese carriers the next day in what came to be called the Battle of Cape Engaño.[22]

Aircraft from the light carrier Independence were able to track the Japanese ships for most of the night and Halsey ordered an air strike of 60 Hellcat fighters, 65 Helldiver dive bombers and 55 Avenger torpedo bombers launched shortly after dawn in anticipation of locating the Japanese fleet. They spotted them at 07:35 and brushed aside the 13 Zeros that the Japanese had retained for self-defense. Zuihō attempted to launch her few remaining aircraft, but was hit by a single bomb on her aft flight deck after a number of torpedo-carrying Avengers missed.[23] The 500-pound (230 kg) bomb started several small fires, lifted the rear elevator, bulged the flight deck, knocked out steering and gave the ship a small list to port. Twenty minutes later, the fires were put out, steering repaired and the list corrected. A second attack an hour later focused on Chiyoda and ignored Zuihō. The third wave arrived around 1300 and badly damaged the ship. She was hit once by a torpedo and twice by small bombs, although fragments from as many as 67 near misses cut steam pipes and caused flooding of both engine rooms and one boiler room. Zuihō was forced to reduce speed to 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) and flooding increased so that all available hands were ordered to man the pumps at 14:10. The ship took on a 13° list to starboard and went dead in the water at 14:45 when the port engine room fully flooded. A fourth wave of American aircraft attacked ten minutes later, but only damaged her with splinters from another ten near misses. This was enough to increase her list to 23° and she was ordered abandoned at 15:10. Zuihō sank at 15:26 at position 19°20′N 125°15′E / 19.333°N 125.250°ECoordinates: 19°20′N 125°15′E / 19.333°N 125.250°E with the loss of 7 officers and 208 men. The destroyer Kuwa and the battleship Ise rescued 58 officers and 701 men between them.[5]

References

- 1 2 3 Peattie, p. 242

- ↑ Jentschura, Jung and Mickel, p. 48

- ↑ Brown, p. 22

- ↑ Jentschura, Jung and Mickel, p. 49

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Tully

- ↑ Parshall & Tully, p. 543

- ↑ Polmar & Genda, pp. 292–96

- ↑ Hata & Izawa, p. 55

- 1 2 3 Hata & Izawa, p. 56

- ↑ Polmar & Genda, p. 377

- ↑ Polmar & Genda, p. 370

- ↑ Polmar & Genda, p. 389

- ↑ Hata & Izawa, p. 83

- ↑ Polmar & Genda, pp. 380–81

- ↑ Brown, pp. 258–60

- ↑ Brown, pp. 263–65

- ↑ Hata & Izawa, pp. 84–85

- 1 2 Hata & Izawa, p. 85

- ↑ Polmar & Genda, p. 415

- ↑ Brown 2009, p. 270

- ↑ Polmar & Genda, p. 412

- ↑ Polmar & Genda, pp. 420, 422, 428

- ↑ Polmar & Genda, pp. 429–30

Bibliography

- Brown, David (1977). WWII Fact Files: Aircraft Carriers. New York: Arco Publishing. ISBN 0-668-04164-1.

- Brown, J. D. (2009). Carrier Operations in World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-108-2.

- Hata, Ikuhiko; Yasuho, Izawa (1989) [1975]. Japanese Naval Aces and Fighter Units in World War II. Gorham, Don Cyril (translator) (translated ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-315-6.

- Jentschura, Hansgeorg; Jung, Dieter; Mickel, Peter (1977). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 0-87021-893-X.

- Parshall, Jonathan; Tully, Anthony (2005). Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway. Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books. ISBN 1-57488-923-0.

- Peattie, Mark (2001). Sunburst: The Rise of Japanese Naval Air Power 1909–1941. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-432-6.

- Polmar, Norman; Genda, Minoru (2006). Aircraft Carriers: A History of Carrier Aviation and Its Influence on World Events. Volume 1, 1909-1945. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books. ISBN 1-57488-663-0.

- Tully, Anthony P. (2007). "IJN Zuiho: Tabular Record of Movement". Kido Butai. Combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

Further reading

- Stille, Mark (2005). Imperial Japanese Navy Aircraft Carriers 1921–1945. New Vanguard 109. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-853-7.

- Stille, Mark (2007). USN Carriers vs IJN Carriers: The Pacific 1942. Duel 6. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-248-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zuihō. |