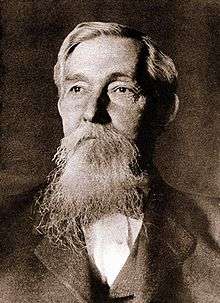

James Lide Coker

Major James Lide Coker (January 3, 1837 in Society Hill, South Carolina – June 25, 1918 in Hartsville, South Carolina) was a businessman, merchant, industrialist, philanthropist, and Civil War veteran, and the founder of Sonoco Products Company and Coker College. He was affectionately known by all as "The Major" after his service in the Confederate Army.

Major Coker was the son of Caleb and Hannah Lide Coker and the great-grandson of Revolutionary War Captains Robert Lide, who moved to South Carolina from Roanoke, Virginia in 1740, and Thomas Coker, who moved to South Carolina from Brunswick, Virginia in 1735. Both men fought in Francis Marion's 2nd South Carolina Regiment at Fort Sullivan in 1776 and the Siege of Charleston in 1779, and were awarded tracts of land along the Pee Dee River following the war.

Major Coker and his descendants' contribution to economic, political, and cultural life in South Carolina is the subject of George Lee Simpson's The Cokers of Carolina: A Social Biography of a Family (UNC Press 1956).

Education and War Service

Educated at St. David's Academy and The Citadel in Charleston, prior to starting his career in agriculture, Major Coker attended Harvard University to study heredity, genetics, and the scientific principles of farming. He married Sue Armstrong Stout in 1860, and they were the parents of nine children, six of whom survived childhood: Margaret, James Lide Jr., David, William, Jennie, Charles Westfield, and Susan.

Major Coker answered the call to defend his state when the Civil War began, and fought for the 6th and 9th South Carolina Regiments at First Manassas, the Battle of Malvern Hill, Second Manassas, the Battle of Harpers Ferry, and Antietam. In October 1863, Major Coker was wounded at the Battle of Chickamauga, and after a time as a prisoner of war, returned home to spend the rest of his life nursing a shattered hip.[1]

In March 1865, Coker set out with a large box of food supplies for the Confederate forces in Richmond. On his return to Hartsville, he learned that General Sherman's army was in the Pee Dee, but Sherman's troops had already destroyed his plantation, the livestock driven away or requisitioned, and everything of value in their home had been taken away. Operation Anaconda devastated the local economy.[2]

Business Acumen

Major Coker's war wounds did not dampen his ambition. He entered into the plantation economy of the day with the stubborn conviction that the South's future hinged on the introduction of scientific principles to farming, coupled with the development of industry.

At the cessation of armed hostilities in April 1865, the Coker family began rebuilding. Although Sherman's army had left no work stock, Major Coker had cotton seed and seed corn, which he planted with the use of an old mule and a pair of oxen borrowed from an uncle. He planted 60 acres (240,000 m2) of cotton and 40 acres (160,000 m2) of corn, which yielded 25 bales of cotton and 300 bushels of corn. At the prevailing prices, 25 bales of cotton brought $1,700, a small fortune in that time.

Using those funds and others derived from mortgaging some of his land, he founded other businesses which were highly successful,[3] including a cotton and naval trade post in Charleston, the Darlington Manufacturing Company, the Hartsville Cotton Mill, the Hartsville Oil Mill, and the Pedigreed Seed Company. Hartsville, South Carolina has enjoyed lasting benefits from his decision to build his own railroad spur (at his own expense) when other town merchants wouldn't agree to help fund construction. In 1881, he organized and was elected president of Darlington National Bank, the only bank in the county.

In 1890, Major Coker and his eldest son, James, began a search for a way to turn Southern pine trees into pulp for papermaking, and three years later, they had perfected a process. Shipping costs for the pulp made this business unprofitable, so Coker purchased his own papermaking equipment. That resulted in the formation of Carolina Fiber Company. With precious few nearby customers for paper, in 1899, the Major organized the Southern Novelty Company, later renamed Sonoco Products Company, to use some of the paper to produce cone-shaped yarn carriers.[4]

Philanthropy and Altruism

Major Coker was the driving force in the establishment of Welsh Neck High School, which later became Coker College for Women in 1908; he gave the college a $50,000 endowment and an additional $600,000 during his years as president, which have played a large part in ensuring its continued existence. In 1909-1910, he funded construction of Davidson Hall; it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1983.[5][6] Memorial Hall was built in 1913 and 1916, and added in 1989.[5]

Coker served his community as mayor of Hartsville, president of the Pee Dee Historical Society, and a member of the South Carolina House of Representatives, where he introduced the first bill for universal public education in South Carolina.

Of all that has been said and written about Major Coker, the words that best describe his philosophy came from his grandson, Charles W. Coker. "Major James L. Coker had some pretty definite ideas about a variety of things. His strongest principle, however, was an absolute inflexibility between what was right and what was wrong. He believed very strongly in the dignity of human beings, and this has been one of the basic philosophies of Sonoco's employee relations policy, customer relations policy, and our stockholder relations policy throughout the years."

Major Coker was inducted into the South Carolina Business Hall of Fame in 1986.

References

- ↑ The Past, Present, and Future of the Library

- ↑ James Lide Coker Papers, 1800-1947 - Manuscripts Division - South Caroliniana Library - University Libraries - USC

- ↑

- Mims, Edwin (September 1911). "The South Realizing Itself, First Article: Hartsville And Its Lesson". The World's Work: A History of Our Time XXII: 14972–14987. Retrieved 2009-07-10.

- ↑ James Lide Coker

- 1 2 Staff (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "Davidson Hall, Coker College, Darlington County (College Ave., Hartsville)". South Carolina Department of Archives and History. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

External links

|