Collective farming

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of agricultural production in which several farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise.[1] This type of collective is essentially an agricultural production cooperative in which member-owners engage jointly in farming activities.

Notable examples of collective farming include the kolkhozy that dominated Soviet agriculture between 1930 and 1991 and the Israeli kibbutzim.[2] Both are collective farms based on common ownership of resources and on pooling of labour and income in accordance with the theoretical principles of cooperative organizations. They differ radically, however, in the application of the cooperative principles relative to freedom of choice and democratic rule. The establishment of kolkhozy in the Soviet Union during the country-wide collectivization campaign of 1928-1933 exemplifies forced collectivization, whereas the kibbutzim in Israel traditionally form through voluntary collectivization and govern themselves as democratic entities. The element of forced or state-sponsored collectivization that operated in many countries during the 20th century led to the impression that collective farms operate under the supervision of the state,[3] but this is not universally true, as shown by the counter-example of the Israeli kibbutzim.

Pre-20th century history

A small group of farming or herding families living together on a jointly-managed piece of land is surely one of the most common living arrangements in all of human history. This has co-existed with, and competed with, more individualistic forms of ownership (as well as state ownership), since the beginnings of agriculture. Private ownership came to predominate in much of the Western world, and is therefore better studied. The process by Western Europe's communal land (and other property) became private is a fundamental question behind views of property: is it the legacy of historical injustices and crimes? Karl Marx believed that what he called primitive communism (joint ownership) was ended by exploitative means he called primitive accumulation. By contrast Libertarian thinkers say that by the homestead principle, whoever is first to work on the land is the rightful owner.

Case studies

Mexico

During the Aztec rule of central Mexico, the country was divided into small territories called calpulli, which were units of local administration concerned with farming as well as education and religion. A calpulli consisted of a number of large extended families with a presumed common ancestor, themselves each composed of a number of nuclear families. Each calpulli owned the land and granted the individual families the right to farm parts of it. When the Spanish conquered Mexico they replaced this with a system of haciendas or estates granted by the Spanish crown to Spanish colonists, as well as the encomienda, a feudal-like right of overlordship colonists were given in particular villages, and the repartimiento or system of indigenous forced labor.

Following the Mexican Revolution, a new constitution in 1917 abolished any remnant of feudal-like rights hacienda owners had over common lands and offered the development of ejidos: communal farms formed on land purchased from the large estates by the Mexican government.

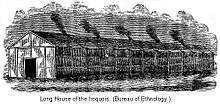

Iroquois and Huron of the North American Great Lakes region

The Huron had an essentially communal system of land ownership. The French Catholic missionary Gabriel Sagard described the fundamentals. The Huron had "as much land as they need[ed]."[4] As a result, the Huron could give families their own land and still have a large amount of excess land owned communally. Any Huron was free to clear the land and farm on the basis of usufruct. He maintained possession of the land as long as he continued to actively cultivate and tend the fields. Once he abandoned the land, it reverted to communal ownership, and anyone could take it up for themselves.[5] While the Huron did seem to have lands designated for the individual, the significance of this possession may be of little relevance; the placement of corn storage vessels in the longhouses, which contained multiple families in one kinship group, suggests the occupants of a given longhouse held all production in common.[6]

The Iroquois had a similar communal system of land distribution. The tribe owned all lands but gave out tracts to the different clans for further distribution among households for cultivation. The land would be redistributed among the households every few years, and a clan could request a redistribution of tracts when the Clan Mothers' Council gathered.[7] Those clans that abused their allocated land or otherwise did not take care of it would be warned and eventually punished by the Clan Mothers' Council by having the land redistributed to another clan.[8] Land property was really only the concern of the women, since it was the women's job to cultivate food and not the men's.[7]

The Clan Mothers' Council also reserved certain areas of land to be worked by the women of all the different clans. Food from such lands, called kěndiǔ"gwǎ'ge' hodi'yěn'tho, would be used at festivals and large council gatherings.[8]

Russian Empire

The obshchina (Russian: общи́на; IPA: [ɐpˈɕːinə], literally: "commune") or mir (Russian: мир, literally: "society" (one of the meanings)) or Selskoye obshestvo (Russian: сельское общество ("Rural community", official term in the 19th and 20th century) were peasant communities, as opposed to individual farmsteads, or khutors, in Imperial Russia. The term derives from the word о́бщий, obshchiy (common).

The vast majority of Russian peasants held their land in communal ownership within a mir community, which acted as a village government and a cooperative. Arable land was divided in sections based on soil quality and distance from the village. Each household had the right to claim one or more strips from each section depending on the number of adults in the household. The purpose of this allocation was not so much social (to each according to his needs) as it was practical (that each person pay his taxes). Strips were periodically re-allocated on the basis of a census, to ensure equitable share of the land. This was enforced by the state, which had an interest in the ability of households to pay their taxes.

Communist collectivization

The Soviet Union introduced collective farming in its constituent republics between 1927 and 1933. The Baltic states and most of the Central and East European countries (except Poland) adopted collective farming after World War II, with the accession of communist regimes to power. In Asia (People's Republic of China, North Korea, Vietnam) the adoption of collective farming was also driven by communist government policies. In most communist countries, the transition to collective farming involved an element of compulsion, while the collective farms within these countries, lacked the principle of voluntary membership, is often regarded at best as being pseudo-cooperatives.

Soviet Union

As part of the First Five-Year Plan, collectivization was introduced in the Soviet Union by General Secretary Joseph Stalin in the late 1920s as a way, according to the policies of socialist leaders, to boost agricultural production through the organization of land and labor into large-scale collective farms (kolkhozy). At the same time, Joseph Stalin argued that collectivization would free poor peasants from economic servitude under the kulaks (wealthy, prosperous farmland owners).

Stalin resorted to mass murder and wholesale deportation of farmers to Siberia in order to implement the plan. Millions who remained did not die of starvation, but the centuries-old system of farming was destroyed in a region so fertile it was once called "the breadbasket of Europe". The immediate effects of forced collectivization were reduced grain output and almost halved livestock numbers, thus creating major famines throughout the USSR during 1932 and 1933. In 1932–1933, an estimated 11 million people, 3–7 million in Ukraine alone,[9] died from famine after Stalin forced the peasants into collectives (Ukrainians call this famine Holodomor). Source:[10] and thousands eyewitness accounts made by the survivors.[11] It was not until 1940 that agricultural production finally surpassed its pre-collectivization levels.[12][13]

Collectivization throughout Moldova was not aggressively pursued until the early 1960s because of the Soviet leadership's focus on a policy of Russification of Moldavians into the Russian way of life. Much of the collectivization in Moldova had undergone in Transnistria, in Chişinău, the present-day capital city of Moldova. Most of the directors who regulated and conducted the process of collectivization were placed by officials from Moscow.

Romania

In Romania, land collectivization began in 1948 and continued for over more than a decade until its virtual eradication in 1962.[14]

Bulgaria

Трудово кооперативно земеделско стопанство was the name of colllective farms in Bulgaria.

Hungary

In Hungary, agricultural collectivization was attempted a number of times between 1948 and 1956 (with disastrous results), until it was finally successful in the early 1960s under János Kádár. The first serious attempt at collectivization based on Stalinist agricultural policy was undertaken in July 1948. Both economic and direct police pressure were used to coerce peasants to join cooperatives, but large numbers opted instead to leave their villages. By the early 1950s, only one-quarter of peasants had agreed to join cooperatives.[15]

In the spring of 1955 the drive for collectivization was renewed, again using physical force to encourage membership, but this second wave also ended in dismal failure. After the events of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, the Hungarian regime opted for a more gradual collectivization drive. The main wave of collectivization occurred between 1959 and 1961, and at the end of this period more than 95% of agricultural land in Hungary had become the property of collective farms. In February 1961, the Central Committee declared that collectivization had been completed.[16]

This quick success should not be confused with enthusiastic adoption of collective idealism on the part of the peasants. Still, demoralized after two successive (and harsh) collectivization campaigns and the events of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, the peasants were less keen to resist. As membership levels increased, those who remained outside likely grew worried about being permanently left out.

Czechoslovakia (1948-90)

In Czechoslovakia, centralized land reforms after World War I allowed for the distribution of most of the land to peasants and the poor, and created large groups of relatively well-to-do farmers (though village poor still existed). These groups showed no support for communist ideals. In 1945, immediately after World War II, new land reform started. The first phase involved a confiscation of properties of Germans, Hungarians, and collaborators of the Nazi regime in accordance with the so-called Beneš decrees. The second phase, promulgated by so-called Ďuriš's laws (after the Communist Minister of Agriculture), in fact meant a complete revision of the pre-war land reform and tried to reduce maximal private property to 150 hectares (ha) of agricultural land and 250 ha of any land (forests, etc...).

The third and final phase forbade possession of land above 50 ha for one family. This phase was carried out in April 1948, two months after Communists took power by force. Farms started to be collectivized, mostly under the threat of sanctions. The most obstinate farmers were persecuted and imprisoned. The most common form of collectivization was agricultural cooperative (in Czech Jednotné zemědělské družstvo, JZD; in Slovak Jednotné roľnícke družstvo, JRD). The collectivization was implemented in three stages (1949–1952, 1953–1956, 1956–1969) and officially ended with implementation of the constitution establishing the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, which made private ownership illegal.

Many early cooperatives collapsed and were recreated again. Their productivity was low since they provided tiny salaries and no pensions, and they failed to create a sense of collective ownership; small-scale pilfering was common, and food became scarce. Seeing the massive outflow of people from agriculture into cities, the government started to massively subsidize the cooperatives in order to make the standard of living of farmers equal to that of city inhabitants; this was the long-term official policy of the government. Funds, machinery, and fertilizers were provided; young people from villages were forced to study agriculture; and students were regularly sent (involuntarily) to help in cooperatives.

Subsidies and constant pressure destroyed the remaining private farmers; only a handful of them remained after the 1960s. The lifestyle of villagers had eventually reached the level of cities, and village poverty was eliminated. Czechoslovakia was again able to produce enough food for its citizens. The price of this success was a huge waste of resources because the cooperatives had no incentive to improve efficiency. Every piece of land was cultivated regardless of the expense involved, and the soil became heavily polluted with chemicals. Also, the intensive use of heavy machinery damaged topsoil. Furthermore, the cooperatives were infamous for over-employment.

In the late 1980s, the economy of Czechoslovakia stagnated, and the state-owned companies were unable to deal with advent of modern technologies. A few agricultural companies (where the rules were less strict than in state companies) used this situation to start providing high-tech products. For example, the only way to buy a PC-compatible computer in the late 1980s was to get it (for an extremely high price) from one agricultural company acting as a reseller.

After the fall of Communism in Czechoslovakia (1989) subsidies to agriculture were halted with devastating effect. Most of the cooperatives had problems competing with technologically advanced foreign competition and were unable to obtain investment to improve their situation. Quite a large percentage of them collapsed. The others that remained were typically insufficiently funded, lacking competent management, without new machinery and living from day to day. Employment in the agricultural sector dropped significantly (from approximately 25% of the population to approximately 1%).

GDR

Collective farms obtained the name Landwirtschaftliche Produktionsgenossenschaft (LPG).

Polish People's Republic

The Polish name of a collective farm was Rolnicza spółdzielnia produkcyjna. Collectivisation in Poland was stopped in 1956, later nationalisation was supported.

SFR Yugoslavia

Collective farming was introduced as government policy throughout Yugoslavia after World War II, by taking away land from wealthy pre-war owners and limiting possessions in private ownership first to 25, and later to 10 hectares. The large, state-owned farms were known as "Agricultural cooperatives" ("Zemljoradničke zadruge" in Serbo-Croatian) and farmers working on them had to meet production quotas in order to satisfy the needs of the populace. The system was largely abolished in the 1950s. See: Law of 23 August 1945 with amendments until 1 December 1948.[17]

People's Republic of China

Mongolia

North Korea

In the late 1990s, the collective farming system collapsed under a strain of droughts. Estimates of deaths due to starvation ranged into the millions, although the government did not allow outside observers to survey the extent of the famine. Aggravating the severity of the famine, the government was accused of diverting international relief supplies to its armed forces. Agriculture in North Korea has suffered tremendously from natural disasters, a lack of fertile land, and government mismanagement, causing the nation to rely on foreign aid as its primary source of food.

Vietnam

The Democratic Republic of Vietnam implemented collective farming although de jure private ownership existed. Starting in 1958 collective farming was pushed such that by 1960, 85% of farmers and 70% of farmlands were collectivized including those seized by force.[18] Collectivization however was seen by the communist leadership as a half-measure when compared to full state ownership.[19]

Following the Fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975, the South Vietnam briefly came under the authority of a Provisional Revolutionary Government, a puppet state under military occupation by North Vietnam, before being officially reunified with the North under Communist rule as the Socialist Republic of Vietnam on July 2, 1976. Upon taking control, the Vietnamese communists banned other political parties, arrested suspects believed to have collaborated with the United States and embarked on a mass campaign of collectivization of farms and factories. Private land ownership was "transformed" to subsume under State and collective ownership.[20] Reconstruction of the war-ravaged country was slow and serious humanitarian and economic problems confronted the communist regime.

In a historic shift in 1986, the Communist Party of Vietnam implemented free-market reforms known as Đổi Mới (Renovation). With the authority of the state remaining unchallenged, private enterprise, deregulation and foreign investment were encouraged. Land ownership nonetheless is the sole prerogative of the state. The economy of Vietnam has achieved rapid growth in agricultural and industrial production, construction and housing, exports and foreign investment. However, the power of the Communist Party of Vietnam over all organs of government remains firm.

Cuba

In the initial years that followed the Cuban Revolution, government authorities experimented with agricultural and farming production cooperatives. Between 1977 and 1983, farmers began to collectivize into CPAs — Cooperativa de Producción Agropecuaria (Agricultural Production Cooperatives). Farmers were encouraged to sell their land to the state for the establishment of a cooperative farm, receiving payments for a period of 20 years while also sharing in the fruits of the CPA. Joining a CPA allowed individuals who were previously dispersed throughout the countryside to move to a centralized location with increased access to electricity, medical care, housing, and schools. Democratic practice tends to be limited to business decisions and is constrained by the centralized economic planning of the Cuban system.

Another type of agricultural production cooperative in Cuba is UBPC — Unidad Básica de Producción Cooperativa (Basic Unit of Cooperative Production). The law authorizing the creation of UBPCs was passed on September 20, 1993. It has been used to transform many state farms into UBPCs, similar to the transformation of Russian sovkhozes (state farms) into kolkhozes (collective farms) since 1992. The law granted indefinite usufruct to the workers of the UBPC in line with its goal of linking the workers to the land. It established material incentives for increased production by tying workers' earnings to the overall production of the UBPC, and increased managerial autonomy and workers' participation in the management of the workplace.

Tanzania

The move to a collective farming method in Tanzania was based on the Soviet model for rural development. In 1967, President Julius Nyerere issued "Socialism and Rural Development" which proposed the creation of Ujamaa Villages. Since the majority of the rural population was spread out, and agriculture was traditionally undertaken individually, the rural population had to be forced to move together, and convinced to farm communally. Following forced migration, incentive to participate in communal farming activities was encouraged by government recognition.

These incentives, in addition to encouraging a degree of participation, also lured those whose primary interests were not the common good to the Ujamaa villages. This, in addition to the Order of 1973 dictating that all people had to live in villages (Operation Vijiji)[21] eroded the sustainability of communal projects. In order for the communal farms to be successful, each member of the village would have to contribute to the best of their ability. Due to lack of sufficient foreign exchange, mechanization of the labour was impossible, therefore it was essential that every villager contributed to manual labour.

Voluntary collective farming

Europe

In modern Europe collective farms are very uncommon. There are intentional communities which practice collective agriculture.[22][23] There is also a growing number of community supported agriculture initiatives, some of which operate under consumer/worker governance, that could be considered collective farms.

India

In Indian villages a single field (normally a plot of three to five acres) may be farmed collectively by the villagers, who each offer labour as a devotional offering, possibly for one or two days per cropping season. The resulting crop belongs to no one individual, and is used as an offering. The labour input is the offering of the peasant in their role as priests. The wealth generated by the sale of the produce belongs to the Gods and hence is Apaurusheya or impersonal. Shrambhakti (labour contributed as devotional offering) is the key instrument for generation of internal resources. The benefits of the harvest are most often redistributed in the village for common good as well as individual need - not as loan or charity, but as divine grace (prasad). The recipient is under no obligation to repay it and no interest need be paid on such gifts. Giving and receiving of these sums is done so discreetly and with such subtle grace that any sense of inferiority on the part of the recipients is obviated.

Israel

Collective farming was also implemented in kibbutzim in Israel, which began in 1909 as a unique combination of Zionism and socialism—known as Labor Zionism. The concept has faced occasional criticism as economically inefficient and over-reliant on subsidized credit.[24]

A lesser-known type of collective farm in Israel is moshav shitufi (lit. collective settlement), where production and services are managed collectively, as in a kibbutz, but consumption decisions are left to individual households. In terms of cooperative organization, moshav shitufi is distinct from the much more common moshav (or moshav ovdim), essentially a village-level service cooperative, not a collective farm.

In 2006 there were 40 moshavim shitufi'im in Israel, compared with 267 kibbutzim.[25]

Collective farming in Israel differs from collectivism in communist states in that it is voluntary. However, including moshavim, various forms of collective farming have traditionally been and remain the primary agricultural model, as there are only a small number of completely private farms in Israel outside of the moshavim.

Mexico

In Mexico the Ejido system provided poor farmers with collective use rights to agricultural land. The erosion of these rights under the 1994 NAFTA agreement directly led to the Chiapas conflict.

Canada and United States

The Anabaptist Hutterites have farmed communally since the 16th century. Most of them now live on the prairies of Canada and the northern Great Plains of the United States.[26]

See also

- Agriculture of Cuba

- Camphill Movement

- Collectivization in the USSR

- Cooperative farming

- CPA (Agriculture) (Cuban Cooperative Farm)

- UBPC (Cuban Cooperative Farm)

- Dekulakization

- Family farm

- Nationalization

- Socialism

- Zadruga

Non-rural collectivization:

References and sources

- References

- ↑ Definition of collective farm in The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1993.

- ↑ Article on large-farm management in Encyclopædia Britannica 2004 CD.

- ↑ Definition of collective farm in The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Third Edition, Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 1992.

- ↑ Axtell 1981, pp. 110–111.

- ↑ Axtell 1981, p. 111.

- ↑ Trigger 1969, p. 28.

- 1 2 Stites 1905, pp. 71–72.

- 1 2 Johansen 1999, p. 123.

- ↑ http://www.faminegenocide.com/resources/hdocuments.htm

- ↑ http://www.holodomorct.org/history.html

- ↑ http://www.holodomorct.org/accounts.html

- ↑ Richard Overy: Russia's War, 1997

- ↑ Eric Hobsbawm: Age of Extremes, 1994

- ↑ A. Sarris and D. Gavrilescu, "Restructuring of farms and agricultural systems in Romania", in: J. Swinnen, A. Buckwell, and E. Mathijs, eds., Agricultural Privatisation, Land Reform and Farm Restructuring in Central and Eastern Europe, Ashgate, Aldershot, UK, 1997.

- ↑ Ivan T. Berend, The Hungarian Economic Reforms 1953-1988, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- ↑ Nigel Swain, Collective Farms Which Work?, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

- ↑ German translation of the Law of 23rd of August 1945 with amendments until 1st of December 1948.

- ↑ XÂY DỰNG CHỦ NGHĨA XÃ HỘI Ở MIỀN BẮC (Building socialism in the North)

- ↑ Vấn đề văn hóa trong tư tưởng Hồ Chí Minh về phát triển đất nước (Culture in Ho Chi Minh's thoughts on national development)

- ↑ Ngành quản lý đất đai Việt Nam: 66 năm phát triển và trưởng thành (Land management in Vietnam, 66 years of development)

- ↑ Lange, Siri. (2008) Land Tenure and Mining In Tanzania. Bergen: Chr. Michelson Institute, p. 2.

- ↑ Longo Mai

- ↑ Camphill movement

- ↑ Y. Kislev, Z. Lerman, P. Zusman, "Recent experience with cooperative farm credit in Israel", Economic Development and Cultural Change, 39(4):773-789 (July 1991).

- ↑ Statistical Abstract of Israel, Central Bureau of Statistics, Jerusalem, 2007.

- ↑ "The Hutterian Bretheren". University of Alberta. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- Sources

- FAO production, 1986, FAO Trade vol. 40, 1986.

- Conquest, Robert, The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine (1986)

- "Peasant Participation in Communal Farming: The Tanzanian Experience" by Dean E. McHenry, Jr. in African Studies Review, Vol. 20, No. 3, Peasants in Africa (Dec., 1977), pp. 43–63.

- "Demography and Development Policy in Tanzania" by Rodger Yeager in The Journal of Developing Areas, Vol. 16, No. 4 (Jul., 1982), pp. 489–510.

External links

- Stalin and Collectivization, by Scott J. Reid

- "The Collectivization 'Genocide'", in Another View of Stalin, by Ludo Martens

- Tony Cliff "Marxism and the collectivisation of agriculture"

- Kiernan, Ben (2007). Blood and soil: a world history of genocide and extermination from Sparta to Darfur. Yale University Press. p. 724. ISBN 978-0-300-10098-3.

|