Joseph Conrad

| Joseph Conrad | |

|---|---|

|

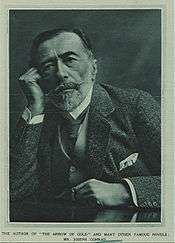

Conrad in 1904 | |

| Born |

Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski 3 December 1857 Terekhove near Berdychiv, Kiev Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died |

3 August 1924 (aged 66) Bishopsbourne, England |

| Resting place | Canterbury Cemetery, Canterbury |

| Occupation | Novelist, short-story writer |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Citizenship | British |

| Period | 1895–1923: Modernism |

| Genre | Fiction |

| Notable works |

The Nigger of the 'Narcissus' (1897) Heart of Darkness (1899) Lord Jim (1900) Typhoon (1902) Nostromo (1904) The Secret Agent (1907) Under Western Eyes (1911) |

| Spouse | Jessie George |

| Children | Borys, John |

|

| |

| Signature |

|

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Polish-British writer regarded as one of the greatest novelists to write in the English language.[1] He was granted British nationality in 1886 but always considered himself a Pole.[2][note 1] Though he did not speak English fluently until he was in his twenties (and always with a marked accent), he was a master prose stylist who brought a distinctly non-English sensibility into English literature.[note 2][3] He wrote stories and novels, many with a nautical setting, that depict trials of the human spirit in the midst of an impassive, inscrutable universe.[note 3]

Joseph Conrad is considered an early modernist, though his works still contain elements of nineteenth-century realism.[4] His narrative style and anti-heroic characters[5] have influenced many authors, including T. S. Eliot, William Faulkner,[6] Graham Greene,[6] and more recently Salman Rushdie.[note 4] Many films have been adapted from, or inspired by, Conrad's works.

Writing in the heyday of the British Empire, Conrad drew on his native Poland's national experiences[note 5] and on his personal experiences in the French and British merchant navies to create short stories and novels that reflect aspects of a European-dominated world, while profoundly exploring human psychology. Appreciated early on by literary critics, his fiction and nonfiction have since been seen as almost prophetic, in the light of subsequent national and international disasters of the 20th and 21st centuries.[7]

Life

Early years

Joseph Conrad was born on 3 December 1857 in Berdychiv, in a part of Ukraine that had belonged to the Kingdom of Poland before 1793 and was at the time of his birth under Russian rule.[8] He was the only child of Apollo Korzeniowski and his wife Ewa Bobrowska. His father was a writer, translator, political activist, and would-be revolutionary. Conrad was christened Józef Teodor Konrad after his maternal grandfather Józef, his paternal grandfather Teodor, and the heroes (both named "Konrad") of two poems by Adam Mickiewicz, Dziady and Konrad Wallenrod. He was subsequently known to his family as "Konrad", rather than "Józef".[note 6]

Though the vast majority of the surrounding area's inhabitants were Ukrainians, and the great majority of Berdychiv's residents were Jewish, almost all the countryside was owned by the Polish szlachta (nobility), to which Conrad's family belonged as bearers of the Nałęcz coat-of-arms.[9] Polish literature, particularly patriotic literature, was held in high esteem by the area's Polish population.[10]:1

The Korzeniowski family played a significant role in Polish attempts to regain independence. Conrad's paternal grandfather served under Prince Józef Poniatowski during Napoleon's Russian campaign and formed his own cavalry squadron during the November 1830 Uprising.[11] Conrad's fiercely patriotic father belonged to the "Red" political faction, whose goal was to re-establish the pre-partition boundaries of Poland, but which also advocated land reform and the abolition of serfdom. Conrad's subsequent refusal to follow in Apollo's footsteps, and his choice of exile over resistance, were a source of lifelong guilt for Conrad.[12][note 7]

Because of the father's attempts at farming and his political activism, the family moved repeatedly. In May 1861 they moved to Warsaw, where Apollo joined the resistance against the Russian Empire. This led to his imprisonment in Pavilion X[note 8] of the Warsaw Citadel.[note 9] Conrad would write: "[I]n the courtyard of this Citadel – characteristically for our nation – my childhood memories begin."[2]:17–19 On 9 May 1862 Apollo and his family were exiled to Vologda, 500 kilometres (310 mi) north of Moscow and known for its bad climate.[2]:19–20 In January 1863 Apollo's sentence was commuted, and the family was sent to Chernihiv in northeast Ukraine, where conditions were much better. However, on 18 April 1865 Ewa died of tuberculosis.[2]:19–25

Apollo did his best to home-school Conrad. The boy's early reading introduced him to the two elements that later dominated his life: in Victor Hugo's Toilers of the Sea he encountered the sphere of activity to which he would devote his youth; Shakespeare brought him into the orbit of English literature. Most of all, though, he read Polish Romantic poetry. Half a century later he explained that "The Polishness in my works comes from Mickiewicz and Słowacki. My father read [Mickiewicz's] Pan Tadeusz aloud to me and made me read it aloud.... I used to prefer [Mickiewicz's] Konrad Wallenrod [and] Grażyna. Later I preferred Słowacki. You know why Słowacki?... [He is the soul of all Poland]".[2]:27

In December 1867, Apollo took his son to the Austrian-held part of Poland, which for two years had been enjoying considerable internal freedom and a degree of self-government. After sojourns in Lwów and several smaller localities, on 20 February 1869 they moved to Kraków (till 1596 the capital of Poland), likewise in Austrian Poland. A few months later, on 23 May 1869, Apollo Korzeniowski died, leaving Conrad orphaned at the age of eleven.[2]:31–34 Like Conrad's mother, Apollo had been gravely ill with tuberculosis.

The young Conrad was placed in the care of Ewa's brother, Tadeusz Bobrowski. Conrad's poor health and his unsatisfactory schoolwork caused his uncle constant problems and no end of financial outlays. Conrad was not a good student; despite tutoring, he excelled only in geography.[2]:43 Since the boy's illness was clearly of nervous origin, the physicians supposed that fresh air and physical work would harden him; his uncle hoped that well-defined duties and the rigors of work would teach him discipline. Since he showed little inclination to study, it was essential that he learn a trade; his uncle saw him as a sailor-cum-businessman who would combine maritime skills with commercial activities.[2]:44–46 In fact, in the autumn of 1871, thirteen-year-old Conrad announced his intention to become a sailor. He later recalled that as a child he had read (apparently in French translation) Leopold McClintock's book about his 1857–59 expeditions in the Fox, in search of Sir John Franklin's lost ships Erebus and Terror.[note 10] He also recalled having read books by the American James Fenimore Cooper and the English Captain Frederick Marryat.[2]:41–42 A playmate of his adolescence recalled that Conrad spun fantastic yarns, always set at sea, presented so realistically that listeners thought the action was happening before their eyes.

In August 1873 Bobrowski sent fifteen-year-old Conrad to Lwów to a cousin who ran a small boarding house for boys orphaned by the 1863 Uprising; group conversation there was in French. The owner's daughter recalled:

He stayed with us ten months... Intellectually he was extremely advanced but [he] disliked school routine, which he found tiring and dull; he used to say... he... planned to become a great writer.... He disliked all restrictions. At home, at school, or in the living room he would sprawl unceremoniously. He... suffer[ed] from severe headaches and nervous attacks...[2]:43–44

Conrad had been at the establishment for just over a year when in September 1874, for uncertain reasons, his uncle removed him from school in Lwów and took him back to Kraków.

On 13 October 1874 Bobrowski sent the sixteen-year-old to Marseilles, France, for a planned career at sea.[2]:44–46 Though Conrad had not completed secondary school, his accomplishments included fluency in French (with a correct accent), some knowledge of Latin, German and Greek, probably a good knowledge of history, some geography, and probably already an interest in physics. He was well read, particularly in Polish Romantic literature. He belonged to only the second generation in his family that had had to earn a living outside the family estates: he was a member of the second generation of the intelligentsia, a social class that was starting to play an important role in Central and Eastern Europe.[2]:46–47 He had absorbed enough of the history, culture and literature of his native land to be able eventually to develop a distinctive world view and make unique contributions to the literature of his adoptive Britain.[10]:1–5 It was tensions that originated in his childhood in Poland and grew in his adulthood abroad that would give rise to Conrad's greatest literary achievements.[10]:246–47 Najder, himself an emigrant from Poland, observes:

Living away from one's natural environment – family, friends, social group, language – even if it results from a conscious decision, usually gives rise to... internal tensions, because it tends to make people less sure of themselves, more vulnerable, less certain of their... position and... value... The Polish szlachta and... intelligentsia were social strata in which reputation... was felt... very important... for a feeling of self-worth. Men strove... to find confirmation of their... self-regard... in the eyes of others... Such a psychological heritage forms both a spur to ambition and a source of constant stress, especially if [one has been inculcated with] the idea of [one]'s public duty...[2]:47

Citizenship

Conrad was a Russian subject, having been born in the Russian part of what had once been the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. In December 1867, with the Russian government's permission, his father Apollo had taken him to the Austrian part of the former Commonwealth, which enjoyed considerable internal freedom and a degree of self-government. After the father's death, Conrad's uncle Bobrowski had attempted to secure Austrian citizenship for him – to no avail, probably because Conrad had not received permission from Russian authorities to remain abroad permanently and had not been released from being a Russian subject. Conrad could not return to Ukraine, in the Russian Empire – he would have been liable to many years' military service and, as the son of political exiles, to harassment.[2]:41

In a letter of 9 August 1877, Conrad's uncle Bobrowski broached two important subjects:[note 11] the desirability of Conrad's naturalisation abroad (tantamount to release from being a Russian subject) and Conrad's plans to join the British merchant marine. "[D]o you speak English?... I never wished you to become naturalized in France, mainly because of the compulsory military service... I thought, however, of your getting naturalized in Switzerland..." In his next letter, Bobrowski supported Conrad's idea of seeking citizenship of the United States or of "one of the more important Southern Republics".[2]:57–58

Eventually Conrad would make his home in England. On 2 July 1886 he applied for British nationality, which was granted on 19 August 1886. Yet, in spite of having become a subject of Queen Victoria, Conrad had not ceased to be a subject of Tsar Alexander III. To achieve the latter, he had to make many visits to the Russian Embassy in London and politely reiterate his request. He would later recall the Embassy's home at Belgrave Square in his novel The Secret Agent.[2]:112 Finally, on 2 April 1889, the Russian Ministry of Home Affairs released "the son of a Polish man of letters, captain of the British merchant marine" from the status of Russian subject.[2]:132

Merchant marine

In 1874 Conrad left Poland to start a merchant-marine career. After nearly four years in France and on French ships, he joined the British merchant marine and for the next fifteen years served under the Red Ensign. He worked on a variety of ships as crew member (steward, apprentice, able-bodied seaman) and then as third, second and first mate, until eventually achieving captain's rank. Of his 19-year merchant-marine career, only about half was spent actually at sea.

Most of Conrad's stories and novels, and many of their characters, were drawn from his seafaring career and persons whom he had met or heard about. For his fictional characters he often borrowed the authentic names of actual persons. The historic trader William Charles Olmeijer, whom Conrad encountered on four short visits to Berau in Borneo, appears as "Almayer" (possibly a simple misspelling) in Conrad's first novel, Almayer's Folly. Other authentic names include those of Captain McWhirr (in Typhoon), Captain Beard and Mr. Mahon (Youth), Captain Lingard (Almayer's Folly and elsewhere), and Captain Ellis (The Shadow Line). Conrad also preserves, in The Nigger of the 'Narcissus', the authentic name of the Narcissus, a ship in which he sailed in 1884.

Conrad's three-year appointment with a Belgian trading company included service as captain of a steamer on the Congo River, an episode that would inspire his novella, Heart of Darkness.

During a brief call in India in 1885–86, 28-year-old Conrad sent five letters to Joseph Spiridion,[note 12] a Pole eight years his senior whom he had befriended at Cardiff in June 1885 just before sailing for Singapore in the clipper ship Tilkhurst. These letters are Conrad's first preserved texts in English. His English is generally correct but stiff to the point of artificiality; many fragments suggest that his thoughts ran along the lines of Polish syntax and phraseology. More importantly, the letters show a marked change in views from those implied in his earlier correspondence of 1881–83. He had departed from "hope for the future" and from the conceit of "sailing [ever] toward Poland", and from his Panslavic ideas. He was left with a painful sense of the hopelessness of the Polish question and an acceptance of England as a possible refuge. While he often adjusted his statements to accord to some extent with the views of his addressees, the theme of hopelessness concerning the prospects for Polish independence often occurs authentically in his correspondence and works before 1914.[2]:104–5

When Conrad left London on 25 October 1892 aboard the clipper ship Torrens, one of the passengers was William Henry Jacques, a consumptive Cambridge graduate who died less than a year later (19 September 1893) and was, according to Conrad's A Personal Record, the first reader of the still-unfinished manuscript of his Almayer's Folly. Jacques encouraged Conrad to continue writing the novel.[2]:181

Conrad completed his last long-distance voyage as a seaman on 26 July 1893 when the Torrens docked at London and "J. Conrad Korzemowin" (per the certificate of discharge) debarked. When the Torrens had left Adelaide on 13 March 1893, the passengers had included two young Englishmen returning from Australia and New Zealand: 25-year-old lawyer and future novelist John Galsworthy; and Edward Lancelot Sanderson, who was going to help his father run a boys' preparatory school at Elstree. They were probably the first Englishmen and non-sailors with whom Conrad struck up a friendship; he would remain in touch with both. The protagonist of one of Galsworthy's first literary attempts, "The Doldrums" (1895–96), the first mate Armand, is obviously modeled on Conrad. At Cape Town, where the Torrens remained from 17 to 19 May, Galsworthy left the ship to look at the local mines. Sanderson continued his voyage and seems to have been the first to develop closer ties with Conrad.[2]:182–3

Writer

In 1894, aged 36, Conrad reluctantly gave up the sea, partly because of poor health, partly due to unavailability of ships, and partly because he had become so fascinated with writing that he had decided on a literary career. His first novel, Almayer's Folly, set on the east coast of Borneo, was published in 1895. Its appearance marked his first use of the pen name "Joseph Conrad"; "Konrad" was, of course, the third of his Polish given names, but his use of it – in the anglicised version, "Conrad" – may also have been an homage to the Polish Romantic poet Adam Mickiewicz's patriotic narrative poem, Konrad Wallenrod.[13]

Edward Garnett, a young publisher's reader and literary critic who would play one of the chief supporting roles in Conrad's literary career, had – like Unwin's first reader of Almayer's Folly, Wilfrid Hugh Chesson – been impressed by the manuscript, but Garnett had been "uncertain whether the English was good enough for publication." Garnett had shown the novel to his wife, Constance Garnett, later a well-known translator of Russian literature. She had thought Conrad's foreignness a positive merit.[2]:197

While Conrad had only limited personal acquaintance with the peoples of Maritime Southeast Asia, the region looms large in his early work. According to Najder, Conrad, the exile and wanderer, was aware of a difficulty that he confessed more than once: the lack of a common cultural background with his Anglophone readers meant he could not compete with English-language authors writing about the Anglosphere. At the same time, the choice of a non-English colonial setting freed him from an embarrassing division of loyalty: Almayer's Folly, and later "An Outpost of Progress" (1897, set in a Congo exploited by King Leopold II of Belgium) and Heart of Darkness (1899, likewise set in the Congo), contain bitter reflections on colonialism. The Malay states came theoretically under the suzerainty of the Dutch government; Conrad did not write about the area's British dependencies, which he never visited. He "was apparently intrigued by... struggles aimed at preserving national independence. The prolific and destructive richness of tropical nature and the dreariness of human life within it accorded well with the pessimistic mood of his early works."[2]:118–20 [note 13]

Almayer's Folly, together with its successor, An Outcast of the Islands (1896), laid the foundation for Conrad's reputation as a romantic teller of exotic tales – a misunderstanding of his purpose that was to frustrate him for the rest of his career.[note 14]

Almost all of Conrad's writings were first published in newspapers and magazines: influential reviews like The Fortnightly Review and the North American Review; avant-garde publications like the Savoy, New Review, and The English Review; popular short-fiction magazines like The Saturday Evening Post and Harper's Magazine; women's journals like the Pictorial Review and Romance; mass-circulation dailies like the Daily Mail and the New York Herald; and illustrated newspapers like The Illustrated London News and the Illustrated Buffalo Express. He also wrote for The Outlook, an imperialist weekly magazine, between 1898 and 1906.[14][note 15]

Financial success long eluded Conrad, who often asked magazine and book publishers for advances, and acquaintances (notably John Galsworthy) for loans.[2][note 16] Eventually a government grant ("Civil List pension") of £100 per annum, awarded on 9 August 1910, somewhat relieved his financial worries,[2]:420 [note 17] and in time collectors began purchasing his manuscripts. Though his talent was early on recognised by the English intellectual elite, popular success eluded him until the 1913 publication of Chance – paradoxically, one of his weaker novels.

Edward Said describes three phases to Conrad's literary career.[15] In the first and longest, from the 1890s to World War I, Conrad writes most of his great novels, including The Nigger of the 'Narcissus' (1897), Heart of Darkness (1899), Lord Jim (1900), Nostromo (1904), The Secret Agent (1907) and Under Western Eyes (1911). The second phase, spanning the war and following the popular success of Chance (1913), is marked by the advent of Conrad's public persona as "great writer". In the third and final phase, from the end of World War I to Conrad's death (1924), he at last finds an uneasy peace; it is, as C. McCarthy writes, as though "the War has allowed Conrad's psyche to purge itself of terror and anxiety."[16]

Personal life

Temperament and health

Conrad was a reserved man, wary of showing emotion. He scorned sentimentality; his manner of portraying emotion in his books was full of restraint, scepticism and irony.[2]:575 In the words of his uncle Bobrowski, as a young man Conrad was "extremely sensitive, conceited, reserved, and in addition excitable. In short [...] all the defects of the Nałęcz family."[2]:65

Conrad suffered throughout life from ill health, physical and mental. A newspaper review of a Conrad biography suggested that the book could have been subtitled Thirty Years of Debt, Gout, Depression and Angst.[17] In 1891 he was hospitalised for several months, suffering from gout, neuralgic pains in his right arm and recurrent attacks of malaria. He also complained of swollen hands "which made writing difficult". Taking his uncle Tadeusz Bobrowski's advice, he convalesced at a spa in Switzerland.[2]:169–70 Conrad had a phobia of dentistry, neglecting his teeth till they had to be extracted. In one letter he remarked that every novel he had written had cost him a tooth.[7]:258 Conrad's physical afflictions were, if anything, less vexatious than his mental ones. In his letters he often described symptoms of depression; "the evidence," writes Najder, "is so strong that it is nearly impossible to doubt it."[2]:167

Attempted suicide

In March 1878, at the end of his Marseilles period, 20-year-old Conrad attempted suicide, by shooting himself in the chest with a revolver.[18] According to his uncle, who was summoned by a friend, Conrad had fallen into debt. Bobrowski described his subsequent "study" of his nephew in an extensive letter to Stefan Buszczyński, his own ideological opponent and a friend of Conrad's late father Apollo.[note 18] To what extent the suicide attempt had been made in earnest, likely will never be known, but it is suggestive of a situational depression.[2]:65–7

Romance and marriage

Little is known about any intimate relationships that Conrad might have had prior to his marriage, confirming a popular image of the author as an isolated bachelor who preferred the company of close male friends.[19] However, in 1888 during a stop-over on Mauritius, Conrad developed a couple of romantic interests. One of these would be described in his 1910 story "A Smile of Fortune", which contains autobiographical elements (e.g., one of the characters is the same Chief Mate Burns who appears in The Shadow Line). The narrator, a young captain, flirts ambiguously and surreptitiously with Alice Jacobus, daughter of a local merchant living in a house surrounded by a magnificent rose garden. Research has confirmed that in Port Louis at the time there was a 17-year-old Alice Shaw, whose father, a shipping agent, owned the only rose garden in town.[2]:126–27

More is known about Conrad's other, more open flirtation. An old friend, Captain Gabriel Renouf of the French merchant marine, introduced him to the family of his brother-in-law. Renouf's eldest sister was the wife of Louis Edward Schmidt, a senior official in the colony; with them lived two other sisters and two brothers. Though the island had been taken over in 1810 by Britain, many of the inhabitants were descendants of the original French colonists, and Conrad's excellent French and perfect manners opened all local salons to him. He became a frequent guest at the Schmidts', where he often met the Misses Renouf. A couple of days before leaving Port Louis, Conrad asked one of the Renouf brothers for the hand of his 26-year-old sister Eugenie. She was already, however, engaged to marry her pharmacist cousin. After the rebuff, Conrad did not pay a farewell visit but sent a polite letter to Gabriel Renouf, saying he would never return to Mauritius and adding that on the day of the wedding his thoughts would be with them.

In March 1896 Conrad married an Englishwoman, Jessie George.[20] The couple had two sons, Borys and John. The elder, Borys, proved a disappointment in scholarship and integrity.[2] Jessie was an unsophisticated, working-class girl, sixteen years younger than Conrad. To his friends, she was an inexplicable choice of wife, and the subject of some rather disparaging and unkind remarks.[21][22] (See Lady Ottoline Morrell's opinion of Jessie in Impressions.) However, according to other biographers such as Frederick Karl, Jessie provided what Conrad needed, namely a "straightforward, devoted, quite competent" companion.[23] Similarly, Jones remarks that, despite whatever difficulties the marriage endured, "there can be no doubt that the relationship sustained Conrad's career as a writer", which might have been a lot less successful without her.[24]

The couple rented a long series of successive homes, occasionally in France, sometimes briefly in London, but mostly in the English countryside, sometimes from friends – to be close to friends, to enjoy the peace of the countryside, but above all because it was more affordable.[2][note 19] Except for several vacations in France and Italy, a 1914 vacation in his native Poland, and a 1923 visit to the United States, Conrad lived the rest of his life in England.

.jpg)

The 1914 vacation with his wife and sons in Poland, at the urging of Józef Retinger, coincided with the outbreak of World War I. On 28 July 1914, the day war broke out between Austro-Hungary and Serbia, Conrad and the Retingers arrived in Kraków (then in the Austro-Hungarian Empire), where Conrad visited childhood haunts. As the city lay only a few miles from the Russian border, there was a risk of getting stranded in a battle zone. With wife Jessie and younger son John ill, Conrad decided to take refuge in the mountain resort town of Zakopane. They left Kraków on 2 August. A few days after arrival in Zakopane, they moved to the Konstantynówka pension operated by Conrad's cousin Aniela Zagórska; it had been frequented by celebrities including the statesman Józef Piłsudski and Conrad's acquaintance, the young concert pianist Artur Rubinstein.[2]:458–63

Zagórska introduced Conrad to Polish writers, intellectuals and artists who had also taken refuge in Zakopane, including novelist Stefan Żeromski and Tadeusz Nalepiński, a writer friend of anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski. Conrad roused interest among the Poles as a famous writer and an exotic compatriot from abroad. He charmed new acquaintances, especially women. However, the double Nobel laureate Maria Skłodowska-Curie's physician sister, Bronisława Dłuska, scolded him for having used his great talent for purposes other than bettering the future of his native land[2]:463–64[note 20]

But thirty-two-year-old Aniela Zagórska (daughter of the pension keeper), Conrad's niece who would translate his works into Polish in 1923–39, idolised him, kept him company, and provided him with books. He particularly delighted in the stories and novels of the ten-years-older, recently deceased Bolesław Prus,[2]:463[25] read everything by his fellow victim of Poland's 1863 Uprising – "my beloved Prus" – that he could get his hands on, and pronounced him "better than Dickens" – a favourite English novelist of Conrad's.[26][note 21]

Conrad, who was noted by his Polish acquaintances to be fluent in his native tongue, participated in their impassioned political discussions. He declared presciently, as Piłsudski had earlier in 1914 in Paris, that in the war, for Poland to regain independence, Russia must be beaten by the Central Powers (the Austro-Hungarian and German Empires), and the latter must in turn be beaten by France and Britain.[2]:464

After many travails and vicissitudes, at the beginning of November 1914 Conrad managed to bring his family back to England. On his return, he was determined to work on swaying British opinion in favour of restoring Poland's sovereignty.[2]:464–68

Jessie Conrad would later write in her memoirs: "I understood my husband so much better after those months in Poland. So many characteristics that had been strange and unfathomable to me before, took, as it were, their right proportions. I understood that his temperament was that of his countrymen."[2]:466

Politics

Conrad [writes Najder] was passionately concerned with politics. [This] is confirmed by several of his works, starting with Almayer's Folly. [...] Nostromo revealed his concern with these matters more fully; it was, of course, a concern quite natural for someone from a country [Poland] where politics was a matter not only of everyday existence but also of life and death. Moreover, Conrad himself came from a social class that claimed exclusive responsibility for state affairs, and from a very politically active family. Norman Douglas sums it up: "Conrad was first and foremost a Pole and like many Poles a politician and moralist malgré lui [French: "in spite of himself"]. These are his fundamentals." [What made] Conrad see political problems in terms of a continuous struggle between law and violence, anarchy and order, freedom and autocracy, material interests and the noble idealism of individuals [...] was Conrad's historical awareness. His Polish experience endowed him with the perception, exceptional in the Western European literature of his time, of how winding and constantly changing were the front lines in these struggles.[27]

The most extensive and ambitious political statement that Conrad ever made was his 1905 essay, "Autocracy and War", whose starting point was the Russo-Japanese War (he finished the article a month before the Battle of Tsushima Strait). The essay begins with a statement about Russia's incurable weakness and ends with warnings against Prussia, the dangerous aggressor in a future European war. For Russia he predicted a violent outburst in the near future, but Russia's lack of democratic traditions and the backwardness of her masses made it impossible for the revolution to have a salutary effect. Conrad regarded the formation of a representative government in Russia as unfeasible and foresaw a transition from autocracy to dictatorship. He saw western Europe as torn by antagonisms engendered by economic rivalry and commercial selfishness. In vain might a Russian revolution seek advice or help from a materialistic and egoistic western Europe that armed itself in preparation for wars far more brutal than those of the past.[2]:351–54

Conrad's "Autocracy and War", Najder points out, showed a historical awareness "exceptional in the Western European literature of his time" – an awareness that Conrad had drawn from his membership in a very politically active family of a country that had for over a century been daily reminded of the consequences of neglecting the broad enlightened interests of the national polity.[2]:352

Conrad's distrust of democracy sprang from his doubts whether the propagation of democracy as an aim in itself could solve any problems. He thought that, in view of the weakness of human nature and of the "criminal" character of society, democracy offered boundless opportunities for demagogues and charlatans.[2]:290

He accused social democrats of his time of acting to weaken "the national sentiment, the preservation of which [was his] concern" – of attempting to dissolve national identities in an impersonal melting-pot. "I look at the future from the depth of a very black past and I find that nothing is left for me except fidelity to a cause lost, to an idea without future." It was Conrad's hopeless fidelity to the memory of Poland that prevented him from believing in the idea of "international fraternity," which he considered, under the circumstances, just a verbal exercise. He resented some socialists' talk of freedom and world brotherhood while keeping silent about his own partitioned and oppressed Poland.[2]:290

Before that, in the early 1880s, letters to Conrad from his uncle Tadeusz[note 22] show Conrad apparently having hoped for an improvement in Poland's situation not through a liberation movement but by establishing an alliance with neighbouring Slavic nations. This had been accompanied by a faith in the Panslavic ideology – "surprising," Najder writes, "in a man who was later to emphasize his hostility towards Russia, a conviction that... Poland's [superior] civilization and... historic... traditions would [let] her play a leading role... in the Panslavic community, [and his] doubts about Poland's chances of becoming a fully sovereign nation-state."[2]:88–89

Conrad's alienation from partisan politics went together with an abiding sense of the thinking man's burden imposed by his personality, as described in an 1894 letter of Conrad's to a relative-by-marriage and fellow author, Marguerite Poradowska (née Gachet, and cousin of Vincent van Gogh's physician, Paul Gachet) of Brussels:

We must drag the chain and ball of our personality to the end. This is the price one pays for the infernal and divine privilege of thought; so in this life it is only the chosen who are convicts – a glorious band which understands and groans but which treads the earth amidst a multitude of phantoms with maniacal gestures and idiotic grimaces. Which would you rather be: idiot or convict?[2]:195

In a 23 October 1922 letter to mathematician-philosopher Bertrand Russell, in response to the latter's book, The Problem of China, which advocated socialist reforms and an oligarchy of sages who would reshape Chinese society, Conrad explained his own distrust of political panaceas:

I have never [found] in any man's book or... talk anything... to stand up... against my deep-seated sense of fatality governing this man-inhabited world.... The only remedy for Chinamen and for the rest of us is [a] change of hearts, but looking at the history of the last 2000 years there is not much reason to expect [it], even if man has taken to flying – a great "uplift" no doubt but no great change....[2]:548–9

Death

On 3 August 1924, Conrad died at his house, Oswalds, in Bishopsbourne, Kent, England, probably of a heart attack. He was interred at Canterbury Cemetery, Canterbury, under a misspelled version of his original Polish name, as "Joseph Teador Conrad Korzeniowski".[2]:573 Inscribed on his gravestone are the lines from Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene which he had chosen as the epigraph to his last complete novel, The Rover:

Sleep after toyle, port after stormie seas,

Ease after warre, death after life, doth greatly please[2]:574

Conrad's modest funeral took place amid great crowds. His old friend Edward Garnett recalled bitterly:

To those who attended Conrad's funeral in Canterbury during the Cricket Festival of 1924, and drove through the crowded streets festooned with flags, there was something symbolical in England's hospitality and in the crowd's ignorance of even the existence of this great writer. A few old friends, acquaintances and pressmen stood by his grave.[2]:573

Another old friend of Conrad's, Cunninghame Graham, wrote Garnett: "Aubry was saying to me... that had Anatole France died, all Paris would have been at his funeral."[2]:573

Twelve years later, Conrad's wife Jessie died on 6 December 1936 and was interred with him.

In 1996 his grave became a Grade II listed building.[28]

Critical reception

Style

Despite the opinions even of some who knew Conrad personally, such as fellow-novelist Henry James,[2]:446–47 Conrad —even when only writing elegantly crafted letters to his uncle and acquaintances —was always at heart a writer who sailed, rather than a sailor who wrote. He used his sailing experiences as a backdrop for many of his works, but he also produced works of similar world view, without the nautical motifs. The failure of many critics to appreciate this caused him much frustration.[2]:377, 562

He wrote oftener about life at sea and in exotic parts than about life on British land because—unlike, for example, his friend John Galsworthy, author of The Forsyte Saga—he knew little about everyday domestic relations in Britain. When Conrad's The Mirror of the Sea was published in 1906 to critical acclaim, he wrote his French translator: "The critics have been vigorously swinging the censer to me.... Behind the concert of flattery, I can hear something like a whisper: 'Keep to the open sea! Don't land!' They want to banish me to the middle of the ocean."[2]:371

An October 1923 visitor to Oswalds, Conrad's home at the time —Cyril Clemens, a cousin of Mark Twain —quoted Conrad as saying: "In everything I have written there is always one invariable intention, and that is to capture the reader's attention."[2]:564

Conrad the artist famously aspired, in the words of his preface to The Nigger of the 'Narcissus' (1897), "by the power of the written word to make you hear, to make you feel... before all, to make you see. That – and no more, and it is everything. If I succeed, you shall find there according to your deserts: encouragement, consolation, fear, charm – all you demand – and, perhaps, also that glimpse of truth for which you have forgotten to ask."[29]

Writing in what to the visual arts was the age of Impressionism, and what to music was the age of impressionist music, Conrad showed himself in many of his works a prose poet of the highest order: for instance, in the evocative Patna and courtroom scenes of Lord Jim; in the scenes of the "melancholy-mad elephant" and the "French gunboat firing into a continent", in Heart of Darkness; in the doubled protagonists of The Secret Sharer; and in the verbal and conceptual resonances of Nostromo and The Nigger of the 'Narcissus'.

Conrad used his own memories as literary material so often that readers are tempted to treat his life and work as a single whole. His "view of the world", or elements of it, are often described by citing at once both his private and public statements, passages from his letters, and citations from his books. Najder warns that this approach produces an incoherent and misleading picture. "An... uncritical linking of the two spheres, literature and private life, distorts each. Conrad used his own experiences as raw material, but the finished product should not be confused with the experiences themselves."[2]:576–77

Many of Conrad's characters were inspired by actual persons he met, including, in his first novel, Almayer's Folly (completed 1894), William Charles Olmeijer, the spelling of whose name Conrad probably altered to "Almayer" inadvertently.[10]:11, 40 The historic trader Olmeijer, whom Conrad encountered on his four short visits to Berau in Borneo, subsequently haunted Conrad's imagination.[10]:40–1 Conrad often borrowed the authentic names of actual individuals, e.g., Captain McWhirr[note 23] (Typhoon), Captain Beard and Mr. Mahon ("Youth"), Captain Lingard (Almayer's Folly and elsewhere), Captain Ellis (The Shadow Line). "Conrad," writes J. I. M. Stewart, "appears to have attached some mysterious significance to such links with actuality."[10]:11–12 Equally curious is "a great deal of namelessness in Conrad, requiring some minor virtuosity to maintain."[10]:244 Thus we never learn the surname of the protagonist of Lord Jim.[10]:95 Conrad also preserves, in The Nigger of the 'Narcissus', the authentic name of the ship, the Narcissus, in which he sailed in 1884.[2]:98–100

Apart from Conrad's own experiences, a number of episodes in his fiction were suggested by past or contemporary publicly known events or literary works. The first half of the 1900 novel Lord Jim (the Patna episode) was inspired by the real-life 1880 story of the SS Jeddah;[10]:96–7 the second part, to some extent by the life of James Brooke, the first White Rajah of Sarawak.[30] The 1901 short story "Amy Foster" was inspired partly by an anecdote in Ford Madox Ford's The Cinque Ports (1900), wherein a shipwrecked sailor from a German merchant ship, unable to communicate in English, and driven away by the local country people, finally found shelter in a pigsty.[2]:312–13 [note 24] In Nostromo (completed 1904), the theft of a massive consignment of silver was suggested to Conrad by a story he had heard in the Gulf of Mexico and later read about in a "volume picked up outside a second-hand bookshop."[10]:128–29 [note 25] The Secret Agent (completed 1906) was inspired by the French anarchist Martial Bourdin's 1894 death while apparently attempting to blow up the Greenwich Observatory.[31] Conrad's story "The Secret Sharer" (completed 1909) was inspired by an 1880 incident when Sydney Smith, first mate of the Cutty Sark, had killed a seaman and fled from justice, aided by the ship's captain.[10]:235–6 The plot of Under Western Eyes (completed 1910) is kicked off by the assassination of a brutal Russian government minister, modelled after the real-life 1904 assassination of Russian Minister of the Interior Vyacheslav von Plehve.[10]:199 The near-novella "Freya of the Seven Isles" (completed in March 1911) was inspired by a story told to Conrad by a Malaya old hand and fan of Conrad's, Captain Carlos M. Marris.[2]:405, 422–23

For the natural surroundings of the high seas, the Malay Archipelago and South America, which Conrad described so vividly, he could rely on his own observations. What his brief landfalls could not provide was a thorough understanding of exotic cultures. For this he resorted, like other writers, to literary sources. When writing his Malayan stories, he consulted Alfred Russel Wallace's The Malay Archipelago (1869), James Brooke's journals, and books with titles like Perak and the Malays, My Journal in Malayan Waters, and Life in the Forests of the Far East. When he set about writing his novel Nostromo, set in the fictitious South American country of Costaguana, he turned to The War between Peru and Chile; Edward Eastwick, Venezuela: or, Sketches of Life in a South American Republic (1868); and George Frederick Masterman, Seven Eventful Years in Paraguay (1869).[10]:130 [note 26] As a result of relying on literary sources, in Lord Jim, as J. I. M. Stewart writes, Conrad's "need to work to some extent from second-hand" led to "a certain thinness in Jim's relations with the... peoples... of Patusan..."[10]:118 This prompted Conrad at some points to alter the nature of Charles Marlow's narrative to "distanc[e] an uncertain command of the detail of Tuan Jim's empire."[10]:119

In keeping with his scepticism[7]:166[10]:163 and melancholy,[10]:16, 18 Conrad almost invariably gives lethal fates to the characters in his principal novels and stories. Almayer (Almayer's Folly, 1894), abandoned by his beloved daughter, takes to opium, and dies;[10]:42 Peter Willems (An Outcast of the Islands, 1895) is killed by his jealous lover Aïssa;[10]:48 the ineffectual "Nigger," James Wait (The Nigger of the 'Narcissus', 1897), dies aboard ship and is buried at sea;[10]:68–9 Mr. Kurtz (Heart of Darkness, 1899) expires, uttering the enigmatic words, "The horror!";[10]:68–9 Tuan Jim (Lord Jim, 1900), having inadvertently precipitated a massacre of his adoptive community, deliberately walks to his death at the hands of the community's leader;[10]:97 in Conrad's 1901 short story, "Amy Foster", a Pole transplanted to England, Yanko Goorall (an English transliteration of the Polish Janko Góral, "Johnny Highlander"), falls ill and, suffering from a fever, raves in his native language, frightening his wife Amy, who flees; next morning Yanko dies of heart failure, and it transpires that he had simply been asking in Polish for water;[note 27] Captain Whalley (The End of the Tether, 1902), betrayed by failing eyesight and an unscrupulous partner, drowns himself;[10]:91 Gian' Battista Fidanza,[note 28] the eponymous respected Italian-immigrant Nostromo (Italian: "Our Man") of the novel Nostromo (1904), illicitly obtains a treasure of silver mined in the South American country of "Costaguana" and is shot dead due to mistaken identity;[10]:124–26 Mr. Verloc, The Secret Agent (1906) of divided loyalties, attempts a bombing, to be blamed on terrorists, that accidentally kills his mentally defective brother-in-law Stevie, and Verloc himself is killed by his distraught wife, who drowns herself by jumping overboard from a channel steamer;[10]:166–68 in Chance (1913), Roderick Anthony, a sailing-ship captain, and benefactor and husband of Flora de Barral, becomes the target of a poisoning attempt by her jealous disgraced financier father who, when detected, swallows the poison himself and dies (some years later, Captain Anthony drowns at sea);[10]:209–11 in Victory (1915), Lena is shot dead by Jones, who had meant to kill his accomplice Ricardo and later succeeds in doing so, then himself perishes along with another accomplice, after which Lena's protector Axel Heyst sets fire to his bungalow and dies beside Lena's body.[10]:220

When a principal character of Conrad's does escape with his life, he sometimes does not fare much better. In Under Western Eyes (1911), Razumov betrays a fellow University of St. Petersburg student, the revolutionist Victor Haldin, who has assassinated a savagely repressive Russian government minister. Haldin is tortured and hanged by the authorities. Later Razumov, sent as a government spy to Geneva, a center of anti-tsarist intrigue, meets the mother and sister of Haldin, who share Haldin's liberal convictions. Razumov falls in love with the sister and confesses his betrayal of her brother; later he makes the same avowal to assembled revolutionists, and their professional executioner bursts his eardrums, making him deaf for life. Razumov staggers away, is knocked down by a streetcar, and finally returns as a cripple to Russia.[10]:185–87

Conrad was keenly conscious of tragedy in the world and in his works. In 1898, at the start of his writing career, he had written to his Scottish writer-politician friend Cunninghame Graham: "What makes mankind tragic is not that they are the victims of nature, it is that they are conscious of it. [A]s soon as you know of your slavery the pain, the anger, the strife – the tragedy begins." But in 1922, near the end of his life and career, when another Scottish friend, Richard Curle, sent Conrad proofs of two articles he had written about Conrad, the latter objected to being characterised as a gloomy and tragic writer. "That reputation... has deprived me of innumerable readers... I absolutely object to being called a tragedian."[2]:544–5

Conrad claimed that he "never kept a diary and never owned a notebook." John Galsworthy, who knew him well, described this as "a statement which surprised no one who knew the resources of his memory and the brooding nature of his creative spirit."[32] Nevertheless, after Conrad's death, Richard Curle published a heavily modified version of Conrad's diaries describing his experiences in the Congo;[33] in 1978 a more complete version was published as The Congo Diary and Other Uncollected Pieces.[34]

Unlike many authors who make it a point not to discuss work in progress, Conrad often did discuss his current work and even showed it to select friends and fellow authors, such as Edward Garnett, and sometimes modified it in the light of their critiques and suggestions.[2]

He also borrowed from other, Polish- and French-language authors, to an extent sometimes skirting plagiarism. When the Polish translation of his 1915 novel Victory appeared in 1931, readers noted striking similarities to Stefan Żeromski's kitschy novel, The History of a Sin (Dzieje grzechu, 1908), including their endings. Comparative-literature scholar Yves Hervouet has demonstrated in the text of Victory a whole mosaic of influences, borrowings, similarities and allusions. He further lists hundreds of concrete borrowings from other, mostly French authors in nearly all of Conrad's works, from Almayer's Folly (1895) to his unfinished Suspense. Conrad seems to have used eminent writers' texts as raw material of the same kind as the content of his own memory. Materials borrowed from other authors often functioned as allusions. Moreover, he had a phenomenal memory for texts and remembered details, "but [writes Najder] it was not a memory strictly categorized according to sources, marshalled into homogeneous entities; it was, rather, an enormous receptacle of images and pieces from which he would draw."[2]:454–7

But [writes Najder] he can never be accused of outright plagiarism. Even when lifting sentences and scenes, Conrad changed their character, inserted them within novel structures. He did not imitate, but (as Hervouet says) "continued" his masters. He was right in saying: "I don't resemble anybody." Ian Watt put it succinctly: "In a sense, Conrad is the least derivative of writers; he wrote very little that could possibly be mistaken for the work of anyone else."[2]:457[note 29]

Conrad, like other artists, faced constraints arising from the need to propitiate his audience and confirm its own favourable self-regard. This may account for his describing the admirable crew of the Judea in his 1898 story "Youth" as "Liverpool hard cases", whereas the crew of the Judea's actual 1882 prototype, the Palestine, had included not a single Liverpudlian, and half the crew had been non-Britons;[2]:94 and for Conrad's turning the real-life 1880 criminally negligent British Captain J. L. Clark, of the SS Jeddah, in his 1900 novel Lord Jim, into the captain of the fictitious Patna – "a sort of renegade New South Wales German" so monstrous in physical appearance as to suggest "a trained baby elephant."[10]:98–103 Similarly, in his letters Conrad – during most of his literary career, struggling for sheer financial survival – often adjusted his views to the predilections of his correspondents.[2]:105 And when he wished to criticise the conduct of European imperialism in what would later be termed the "Third World", he turned his gaze upon the Dutch and Belgian colonies, not upon the British Empire.[2]:119

The singularity of the universe depicted in Conrad's novels, especially compared to those of near-contemporaries like his friend and frequent benefactor John Galsworthy, is such as to open him to criticism similar to that later applied to Graham Greene.[35] But where "Greeneland" has been characterised as a recurring and recognisable atmosphere independent of setting, Conrad is at pains to create a sense of place, be it aboard ship or in a remote village; often he chose to have his characters play out their destinies in isolated or confined circumstances. In the view of Evelyn Waugh and Kingsley Amis, it was not until the first volumes of Anthony Powell's sequence, A Dance to the Music of Time, were published in the 1950s, that an English novelist achieved the same command of atmosphere and precision of language with consistency, a view supported by later critics like A. N. Wilson; Powell acknowledged his debt to Conrad. Leo Gurko, too, remarks, as "one of Conrad's special qualities, his abnormal awareness of place, an awareness magnified to almost a new dimension in art, an ecological dimension defining the relationship between earth and man."[36]

T. E. Lawrence, one of many writers whom Conrad befriended, offered some perceptive observations about Conrad's writing:

He's absolutely the most haunting thing in prose that ever was: I wish I knew how every paragraph he writes (...they are all paragraphs: he seldom writes a single sentence...) goes on sounding in waves, like the note of a tenor bell, after it stops. It's not built in the rhythm of ordinary prose, but on something existing only in his head, and as he can never say what it is he wants to say, all his things end in a kind of hunger, a suggestion of something he can't say or do or think. So his books always look bigger than they are. He's as much a giant of the subjective as Kipling is of the objective. Do they hate one another?[7]:343

In Conrad's time, literary critics, while usually commenting favourably on his works, often remarked that many readers were put off by his exotic style, complex narration, profound themes, and pessimistic ideas. Yet, as his ideas were borne out by ensuing 20th-century events, in due course he came to be admired for beliefs that seemed to accord more closely with subsequent times than with his own.

Conrad's was a starkly lucid view of the human condition – a vision similar to that which had been offered in two micro-stories by his ten-years-older Polish compatriot, Bolesław Prus (whose work Conrad greatly admired):[note 30] "Mold of the Earth" (1884) and "Shades" (1885). Conrad wrote:

Faith is a myth and beliefs shift like mists on the shore; thoughts vanish; words, once pronounced, die; and the memory of yesterday is as shadowy as the hope of to-morrow....In this world – as I have known it – we are made to suffer without the shadow of a reason, of a cause or of guilt....

There is no morality, no knowledge and no hope; there is only the consciousness of ourselves which drives us about a world that... is always but a vain and fleeting appearance....

A moment, a twinkling of an eye and nothing remains – but a clod of mud, of cold mud, of dead mud cast into black space, rolling around an extinguished sun. Nothing. Neither thought, nor sound, nor soul. Nothing.[7]:166

In a letter of late December 1897 to Cunninghame Graham, Conrad metaphorically described the universe as a huge machine:

It evolved itself (I am severely scientific) out of a chaos of scraps of iron and behold! – it knits. I am horrified at the horrible work and stand appalled. I feel it ought to embroider – but it goes on knitting. You come and say: "this is all right; it's only a question of the right kind of oil. Let us use this – for instance – celestial oil and the machine shall embroider a most beautiful design in purple and gold." Will it? Alas no. You cannot by any special lubrication make embroidery with a knitting machine. And the most withering thought is that the infamous thing has made itself; made itself without thought, without conscience, without foresight, without eyes, without heart. It is a tragic accident –and it has happened. You can't interfere with it. The last drop of bitterness is in the suspicion that you can't even smash it. In virtue of that truth one and immortal which lurks in the force that made it spring into existence it is what it is – and it is indestructible!

It knits us in and it knits us out. It has knitted time space, pain, death, corruption, despair and all the illusions – and nothing matters.[2]:253

Conrad is the novelist of man in extreme situations. "Those who read me," he wrote in the preface to A Personal Record, "know my conviction that the world, the temporal world, rests on a few very simple ideas; so simple that they must be as old as the hills. It rests, notably, among others, on the idea of Fidelity."

For Conrad fidelity is the barrier man erects against nothingness, against corruption, against the evil that is all about him, insidious, waiting to engulf him, and that in some sense is within him unacknowledged. But what happens when fidelity is submerged, the barrier broken down, and the evil without is acknowledged by the evil within? At his greatest, that is Conrad's theme.[1]

What is the essence of Conrad's art? It surely is not the plot, which he – like Shakespeare – often borrows from public sources and which could be duplicated by lesser authors; the plot serves merely as the vehicle for what the author has to say. A focus on plot leads to the absurdity of Charles and Mary Lamb's 1807 Tales from Shakespeare. Rather, Conrad's essence is to be sought in his depiction of the world open to our senses, and in the world view that he has evolved in the course of experiencing that outer, and his own inner, world. An evocative part of that view is expressed in an August 1901 letter that Conrad wrote to the editor of The New York Times Saturday Book Review:

Egoism, which is the moving force of the world, and altruism, which is its morality, these two contradictory instincts, of which one is so plain and the other so mysterious, cannot serve us unless in the incomprehensible alliance of their irreconcilable antagonism.[2]:315 [note 31]

Language

Conrad spoke both his native Polish language and the French language fluently from childhood and only acquired English in his twenties. Why then did he choose to write his books in, effectively, his third language? He states in his preface to A Personal Record that writing in English was for him "natural", and that the idea of his having made a deliberate choice between English and French, as some had suggested, was in error. He explained that, though he was familiar with French from childhood, "I would have been afraid to attempt expression in a language so perfectly 'crystallized'."[37]:iv-x In a 1915 conversation with American sculptor Jo Davidson, as he posed for his bust, in response to Davidson's question Conrad said: "Ah… to write French you have to know it. English is so plastic—if you haven't got a word you need you can make it, but to write French you have to be an artist like Anatole France."[38] These statements, as so often happens in Conrad's "autobiographical" writings, are subtly disingenuous.[2] In 1897 Conrad was paid a visit by a fellow Pole, Wincenty Lutosławski, who was intent on imploring Conrad to write in Polish and "to win Conrad for Polish literature". Lutosławski recalls that during their conversation Conrad explained why he did not write in Polish: "I value too much our beautiful Polish literature to introduce into it my worthless twaddle. But for Englishmen my capacities are just sufficient: they enable me to earn my living". Perhaps revealingly, Conrad later wrote to Lutosławski to keep his visit a secret.[39]

More to the point is Conrad's remark in A Personal Record that English was "the speech of my secret choice, of my future, of long friendships, of the deepest affections, of hours of toil and hours of ease, and of solitary hours, too, of books read, of thoughts pursued, of remembered emotions—of my very dreams!"[37]:252 In 1878 Conrad's four-year experience in the French merchant marine had been cut short when the French discovered that he did not have a permit from the Imperial Russian consul to sail with the French.[note 32] This, and some typically disastrous Conradian investments, had left him destitute and had precipitated a suicide attempt. With the concurrence of his uncle Bobrowski, who had been summoned to Marseilles, Conrad decided to seek employment with the British merchant marine, which did not require Russia's permission.[2]:64–66 Thus began Conrad's sixteen years' seafarer's acquaintance with the British and with the English language.

Had Conrad remained in the Francophone sphere or had he returned to Poland, the son of the Polish poet, playwright and translator Apollo Korzeniowski – from childhood exposed to Polish and foreign literature, and ambitious to himself become a writer[2]:43–44 –might have ended writing in French or Polish instead of English. Certainly his mentor-uncle Tadeusz Bobrowski thought Conrad might write in Polish; in an 1881 letter he advised his 23-year-old nephew:

As, thank God, you do not forget your Polish... and your writing is not bad, I repeat what I have... written and said before – you would do well to write... for Wędrowiec [The Wanderer] in Warsaw. We have few travelers, and even fewer genuine correspondents: the words of an eyewitness would be of great interest and in time would bring you... money. It would be an exercise in your native tongue—that thread which binds you to your country and countrymen—and finally a tribute to the memory of your father who always wanted to and did serve his country by his pen.[2]:86

Inescapably, Conrad's third language, English, remained under the influence of his first two languages – Polish and French. This makes his English seem unusual. Najder observes:

[H]e was a man of three cultures: Polish, French, and English. Brought up in a Polish family and cultural environment... he learned French as a child, and at the age of less than seventeen went to France, to serve... four years in the French merchant marine. At school he must have learned German, but French remained the language he spoke with greatest fluency (and no foreign accent) until the end of his life. He was well versed in French history and literature, and French novelists were his artistic models. But he wrote all his books in English—the tongue he started to learn at the age of twenty. He was thus an English writer who grew up in other linguistic and cultural environments. His work can be seen as located in the borderland of auto-translation [emphasis added by Wikipedia].[2]:IX

Inevitably for a trilingual Polish–French–English-speaker, Conrad's writings occasionally show examples of "Franglais" and "Poglish" – of the inadvertent use of French or Polish vocabulary, grammar or syntax in his English compositions. In one instance, Najder uses "several slips in vocabulary, typical for Conrad (Gallicisms) and grammar (usually Polonisms)" as part of internal evidence against Conrad's sometime literary collaborator Ford Madox Ford's claim to have written a certain instalment of Conrad's novel Nostromo, for serialised publication in T. P.'s Weekly, on behalf of an ill Conrad.[2]:341–42

The impracticality of working with a language which has long ceased to be one's principal language of daily use is illustrated by Conrad's 1921 attempt at translating into English the Polish columnist and comedy-writer Bruno Winawer's short play, The Book of Job. Najder writes:

[T]he [play's] language is easy, colloquial, slightly individualized. Particularly Herup and a snobbish Jew, "Bolo" Bendziner, have their characteristic ways of speaking. Conrad, who had had little contact with everyday spoken Polish, simplified the dialogue, left out Herup's scientific expressions, and missed many amusing nuances. The action in the original is quite clearly set in contemporary Warsaw, somewhere between elegant society and the demimonde; this specific cultural setting is lost in the translation. Conrad left out many accents of topical satire in the presentation of the dramatis personae and ignored not only the ungrammatical speech (which might have escaped him) of some characters but even the Jewishness of two of them, Bolo and Mosan.[2]:538–39

As a practical matter, by the time Conrad set about writing fiction, he had little choice but to write in English.[note 33] Poles who accused Conrad of cultural apostasy because he wrote in English instead of Polish,[2]:292–95, 463–64 missed the point – as do Anglophones who see, in Conrad's default choice of English as his artistic medium, a testimonial to some sort of innate superiority of the English language.[note 34] According to Conrad's close friend and literary assistant Richard Curle, the fact of Conrad writing in English was "obviously misleading" because Conrad "is no more completely English in his art than he is in his nationality".[40]:223 Moreover, Conrad "could never have written in any other language save the English language....for he would have been dumb in any other language but the English."[40]:227–28

Conrad always retained a strong emotional attachment to his native language. He asked his visiting Polish niece Karola Zagórska, "Will you forgive me that my sons don't speak Polish?"[2]:481 In June 1924, shortly before his death, he apparently expressed a desire that his son John marry a Polish girl and learn Polish, and toyed with the idea of returning for good to now independent Poland.[2]:571

Controversy

In 1975 the Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe published an essay, "An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad's 'Heart of Darkness'", which provoked controversy by calling Conrad a "thoroughgoing racist". Achebe's view was that Heart of Darkness cannot be considered a great work of art because it is "a novel which celebrates... dehumanisation, which depersonalises a portion of the human race." Referring to Conrad as a "talented, tormented man", Achebe notes that Conrad (via the protagonist, Charles Marlow) reduces and degrades Africans to "limbs", "angles", "glistening white eyeballs", etc. while simultaneously (and fearfully) suspecting a common kinship between himself and these natives—leading Marlow to sneer the word "ugly."[41] Achebe also cited Conrad's description of an encounter with an African: "A certain enormous buck nigger encountered in Haiti fixed my conception of blind, furious, unreasoning rage, as manifested in the human animal to the end of my days."[42] Achebe's essay, a landmark in postcolonial discourse, provoked debate, and the questions it raised have been addressed in most subsequent literary criticism of Conrad.[43][44]

Achebe's critics argue that he fails to distinguish Marlow's view from Conrad's, which results in very clumsy interpretations of the novella.[45] In their view, Conrad portrays Africans sympathetically and their plight tragically, and refers sarcastically to, and condemns outright, the supposedly noble aims of European colonists, thereby demonstrating his skepticism about the moral superiority of white men.[46] This, indeed, is a central theme of the novel; Marlow's experiences in Africa expose the brutality of colonialism and its rationales. Ending a passage that describes the condition of chained, emaciated slaves, the novelist remarks: "After all, I also was a part of the great cause of these high and just proceedings." Some observers assert that Conrad, whose native country had been conquered by imperial powers, empathised by default with other subjugated peoples.[47] Jeffrey Meyers notes that Conrad, like his acquaintance Roger Casement, "was one of the first men to question the Western notion of progress, a dominant idea in Europe from the Renaissance to the Great War, to attack the hypocritical justification of colonialism and to reveal... the savage degradation of the white man in Africa."[7]:100–1 Likewise, E.D. Morel, who led international opposition to King Leopold II's rule in the Congo, saw Conrad's Heart of Darkness as a condemnation of colonial brutality and referred to the novella as "the most powerful thing written on the subject."[48]

Conrad scholar Peter Firchow writes that "nowhere in the novel does Conrad or any of his narrators, personified or otherwise, claim superiority on the part of Europeans on the grounds of alleged genetic or biological difference". If Conrad or his novel is racist, it is only in a weak sense, since Heart of Darkness acknowledges racial distinctions "but does not suggest an essential superiority" of any group.[49][50] Achebe's reading of Heart of Darkness can be (and has been) challenged by a reading of Conrad's other African story, "An Outpost of Progress", which has an omniscient narrator, rather than the embodied narrator, Marlow. Some younger scholars, such as Masood Ashraf Raja, have also suggested that if we read Conrad beyond Heart of Darkness, especially his Malay novels, racism can be further complicated by foregrounding Conrad's positive representation of Muslims.[51]

In 1998 H.S. Zins wrote in Pula: Botswana Journal of African Studies:

Conrad made English literature more mature and reflective because he called attention to the sheer horror of political realities overlooked by English citizens and politicians. The case of Poland, his oppressed homeland, was one such issue. The colonial exploitation of Africans was another. His condemnation of imperialism and colonialism, combined with sympathy for its persecuted and suffering victims, was drawn from his Polish background, his own personal sufferings, and the experience of a persecuted people living under foreign occupation. Personal memories created in him a great sensitivity for human degradation and a sense of moral responsibility."[52]

Conrad's experience in the Belgian-run Congo made him one of the fiercest critics of the "white man's mission." It was also, writes Najder, Conrad's most daring and last "attempt to become... a cog in the mechanism of society. By accepting the job in the trading company, he joined, for once in his life, an organized, large-scale group activity on land. [After that, u]ntil his death he remained a recluse in the social sense and never became involved with any institution or clearly defined group of people."[2]:164–5

Memorials

An anchor-shaped monument to Conrad at Gdynia, on Poland's Baltic Seacoast, features a quotation from him in Polish: "Nic tak nie nęci, nie rozczarowuje i nie zniewala, jak życie na morzu" ("[T]here is nothing more enticing, disenchanting, and enslaving than the life at sea" – Lord Jim, chapter 2, paragraph 1).

In Circular Quay, Sydney, Australia, a plaque in a "writers walk" commemorates Conrad's visits to Australia between 1879 and 1892. The plaque notes that "Many of his works reflect his 'affection for that young continent.'"[53]

In San Francisco in 1979, a small triangular square at Columbus Avenue and Beach Street, near Fisherman's Wharf, was dedicated as "Joseph Conrad Square" after Conrad. The square's dedication was timed to coincide with release of Francis Ford Coppola's Heart of Darkness-inspired film, Apocalypse Now.

In the latter part of World War II, the Royal Navy cruiser HMS Danae was rechristened ORP Conrad and served as part of the Polish Navy.

Notwithstanding the undoubted sufferings that Conrad endured on many of his voyages, sentimentality and canny marketing place him at the best lodgings in several of his destinations. Hotels across the Far East still lay claim to him as an honoured guest, with, however, no evidence to back their claims: Singapore's Raffles Hotel continues to claim he stayed there though he lodged, in fact, at the Sailors' Home nearby. His visit to Bangkok also remains in that city's collective memory, and is recorded in the official history of The Oriental Hotel (where he never, in fact, stayed, lodging aboard his ship, the Otago) along with that of a less well-behaved guest, Somerset Maugham, who pilloried the hotel in a short story in revenge for attempts to eject him.

A plaque commemorating "Joseph Conrad–Korzeniowski" has been installed near Singapore's Fullerton Hotel.

Conrad is also reported to have stayed at Hong Kong's Peninsula Hotel—a port that, in fact, he never visited. Later literary admirers, notably Graham Greene, followed closely in his footsteps, sometimes requesting the same room and perpetuating myths that have no basis in fact. No Caribbean resort is yet known to have claimed Conrad's patronage, although he is believed to have stayed at a Fort-de-France pension upon arrival in Martinique on his first voyage, in 1875, when he travelled as a passenger on the Mont Blanc.

In April 2013, a monument to Conrad was unveiled in the Russian town of Vologda, where he and his parents lived in exile in 1862–63.

Legacy

After the publication of Chance in 1913, Conrad was the subject of more discussion and praise than any other English writer of the time. He had a genius for companionship, and his circle of friends, which he had begun assembling even prior to his first publications, included authors and other leading lights in the arts, such as Henry James, Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham, John Galsworthy, Edward Garnett, Garnett's wife Constance Garnett (translator of Russian literature), Stephen Crane, Hugh Walpole, George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, Arnold Bennett, Norman Douglas, Jacob Epstein, T. E. Lawrence, André Gide, Paul Valéry, Maurice Ravel, Valery Larbaud, Saint-John Perse, Edith Wharton, James Huneker, anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski, Józef Retinger (later a founder of the European Movement, which led to the European Union, and author of Conrad and His Contemporaries). Conrad encouraged and mentored younger writers.[2] In the early 1900s he composed a short series of novels in collaboration with Ford Madox Ford.[54]

In 1919 and 1922 Conrad's growing renown and prestige among writers and critics in continental Europe fostered his hopes for a Nobel Prize in Literature. Interestingly, it was apparently the French and Swedes – not the English – who favoured Conrad's candidacy.[2]:512, 550 [note 35]

In April 1924 Conrad, who possessed a hereditary Polish status of nobility and coat-of-arms (Nałęcz), declined a (non-hereditary) British knighthood offered by Labour Party Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald.[note 36] [note 37] Conrad kept a distance from official structures — he never voted in British national elections — and seems to have been averse to public honours generally; he had already refused honorary degrees from Cambridge, Durham, Edinburgh, Liverpool, and Yale universities.[2]:570

Of Conrad's novels, Lord Jim (1900) and Nostromo (1904) are widely read as set texts and for pleasure. The Nigger of the 'Narcissus' (1897), The Secret Agent (1907) and Under Western Eyes (1911) are also considered among his finest novels. Arguably his most influential work remains Heart of Darkness (1899), to which many have been introduced by Francis Ford Coppola's film, Apocalypse Now (1979), inspired by Conrad's novel and set during the Vietnam War; the novel's depiction of a journey into the darkness of the human psyche resonates with modern readers. Conrad's short stories, other novels, and nonfiction writings also continue to find favour with many readers and filmmakers.

In the People's Republic of Poland, translations of Conrad's works were published – all except Under Western Eyes, banned by the censors due to its advocacy of fairness and neutrality. Under Western Eyes was published in Poland in the 1980s as an underground "bibuła".[55]

Joseph Conrad was an influence on many subsequent writers, including D. H. Lawrence, T. S. Eliot, Maria Dąbrowska,[56] F. Scott Fitzgerald,[6] William Faulkner,[6] Gerald Basil Edwards,[57] Ernest Hemingway,[58] Antoine de Saint-Exupéry,[56] André Malraux,[56] George Orwell,[7]:254 Graham Greene,[6] Malcolm Lowry, William Golding,[6] William S. Burroughs, Joseph Heller, Italo Calvino, Gabriel García Márquez,[6] J. G. Ballard, Chinua Achebe, John le Carré,[6] V. S. Naipaul,[6] Philip Roth,[59] Hunter S. Thompson, J. M. Coetzee,[6] Stephen R. Donaldson, and Salman Rushdie.[note 38]

Impressions

A striking portrait of Conrad, aged about 46, was drawn by the historian and poet Henry Newbolt, who met him about 1903:

One thing struck me at once—the extraordinary difference between his expression in profile and when looked at full face. [W]hile the profile was aquiline and commanding, in the front view the broad brow, wide-apart eyes and full lips produced the effect of an intellectual calm and even at times of a dreaming philosophy. Then [a]s we sat in our little half-circle round the fire, and talked on anything and everything, I saw a third Conrad emerge—an artistic self, sensitive and restless to the last degree. The more he talked the more quickly he consumed his cigarettes... And presently, when I asked him why he was leaving London after... only two days, he replied that... the crowd in the streets... terrified him. "Terrified? By that dull stream of obliterated faces?" He leaned forward with both hands raised and clenched. "Yes, terrified: I see their personalities all leaping out at me like tigers!" He acted the tiger well enough almost to terrify his hearers: but the moment after he was talking again wisely and soberly as if he were an average Englishman with not an irritable nerve in his body.[2]:331

On 12 October 1912, American music critic James Huneker visited Conrad and later recalled being received by "a man of the world, neither sailor nor novelist, just a simple-mannered gentleman, whose welcome was sincere, whose glance was veiled, at times far-away, whose ways were French, Polish, anything but 'literary,' bluff or English."[2]:437

After respective separate visits to Conrad in August and September 1913, two British aristocrats, the socialite Lady Ottoline Morrell and the mathematician and philosopher Bertrand Russell – who were lovers at the time – recorded their impressions of the novelist. In her diary, Morrell wrote:

I found Conrad himself standing at the door of the house ready to receive me. How different from the [disparaging] picture Henry James had evoked [in conversation with Morrell], for Conrad's appearance was really that of a Polish nobleman. His manner was perfect, almost too elaborate; so nervous and sympathetic that every fibre of him seemed electric... He talked English with a strong accent, as if he tasted his words in his mouth before pronouncing them; but he talked extremely well, though he had always the talk and manner of a foreigner... He was dressed very carefully in a blue double-breasted jacket. He talked... apparently with great freedom about his life – more ease and freedom indeed than an Englishman would have allowed himself. He spoke of the horrors of the Congo, from the moral and physical shock of which he said he had never recovered... [His wife Jessie] seemed a nice and good-looking fat creature, an excellent cook, as Henry James [had] said, and was indeed a good and reposeful mattress for this hypersensitive, nerve-wracked man, who did not ask from his wife high intelligence, only an assuagement of life's vibrations.... He made me feel so natural and very much myself, that I was almost afraid of losing the thrill and wonder of being there, although I was vibrating with intense excitement inside; and even now, as I write this, I feel almost the same excitement, the same thrill of having been in the presence of one of the most remarkable men I have known. His eyes under their pent-house lids revealed the suffering and the intensity of his experiences; when he spoke of his work, there came over them a sort of misty, sensuous, dreamy look, but they seemed to hold deep down the ghosts of old adventures and experiences – once or twice there was something in them one almost suspected of being wicked.... But then I believe whatever strange wickedness would tempt this super-subtle Pole, he would be held in restraint by an equally delicate sense of honour.... In his talk he led me along many paths of his life, but I felt that he did not wish to explore the jungle of emotions that lay dense on either side, and that his apparent frankness had a great reserve. This may perhaps be characteristic of Poles as it is of the Irish.[2]:447

A month later, Bertrand Russell visited Conrad at Capel House, and the same day on the train wrote down his impressions: