Ivar the Boneless

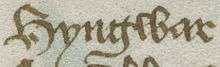

Ivar the Boneless (Old Norse: Ívarr hinn Beinlausi; Old English: Hyngwar) was a Viking leader and a commander of the Great Heathen Army which invaded the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England, starting in 865. According to the tradition recorded in the Norse sagas, he was one of the sons of Ragnar Lothbrok, and his brothers included Björn Ironside, Halfdan Ragnarsson, Sigurd Snake-in-the-Eye and Ubba. He is often considered identical to Ímar, the founder of the Uí Ímair dynasty, which dominated the Irish Sea region throughout the Viking Age.

Biography

Ivar was one of the leaders from the Great Heathen Army which invaded the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of East Anglia in 865.[2][3] According to the Norse sagas this invasion was organised by the sons of Ragnar Lodbrok, of whom Ivar was one, to wreak revenge against Ælla of Northumbria. Ælla had supposedly executed Ragnar in 865 by throwing him in a snake pit, but the historicity of this explanation is unknown.[4][5] The invaders are usually identified as Danes, although the tenth-century churchman Asser stated in Latin that the invaders came "de Danubia", which translates into English as "from the Danube", the fact that a part of the Danube is located in what was known in Latin as Dacia suggests that Asser may have actually intended Dania, a Latin term for Denmark.[6]

The Great Heathen Army landed in East Anglia in the autumn of 865, where they remained over the winter and secured horses for their later efforts.[7] The following year the army headed north and invaded Northumbria, which was in the midst of a civil war between Ælla and Osberht, warring claimants for the Northumbrian throne.[8] Late in 866 the army conquered the rich Northumbrian settlement of York.[9] The following year Ælla and Osberht put their differences aside, and teamed up to retake the town. The attempt was a disaster and both of them lost their lives.[8] According to legend, Ælla was captured alive, but was executed by Ivar and his brothers using the blood eagle, a method of execution whereby the ribcage is opened from behind and the lungs are pulled out, forming a wing-like shape.[3] With no obvious leader, Northumbrian resistance was crushed and the Danes installed a puppet-king, Ecgberht, to rule in their name and collect taxes for their army.[10]

Later in the year the Army moved south and invaded the kingdom of Mercia, capturing the town of Nottingham, where they spent the winter.[9] The Mercian king, Burghred, responded by allying with the West Saxon king Æthelred, and with a combined force they laid siege to the town. The Anglo-Saxons were unable to recapture the city, but a truce was agreed whereby the Danes would withdraw to York.[11] The Great Heathen Army remained in York for over a year, gathering its strength for further assaults.[8]

The Danes returned to East Anglia in 869, this time intent on conquest. They seized Thetford, with the intention of remaining there over winter, but they were confronted by an East Anglian army.[12] The East Anglian army was defeated and their king, Edmund, was slain.[13] Medieval tradition identifies Edmund as a martyr who refused the Danes' demand to renounce Christ, and was killed for his steadfast Christianity.[14] Ivar and Ubba are identified as the commanders of the Danes, and the killers of Edmund.[15] How true the later accounts of Edmund's death are is unknown, but it has been suggested that his capture and execution is not an unlikely thing to have happened.[14]

Following the conquest of East Anglia, Ivar apparently left the Great Heathen Army - his name disappears from English records after 870.[11]

Identification with Ímar

Ivar is usually identified with Ímar, apparent ancestor and founder of the Uí Ímair, or House of Ivar, a dynasty which at various times from the mid-9th through the 10th century ruled Northumbria from the capital of York, and dominated the Irish Sea region from the Kingdom of Dublin.[16]

Death

Ivar disappears from the historic record sometime after 870. His ultimate fate is uncertain. The Anglo-Saxon chronicler Æthelweard records his death as 870.[17] The Annals of Ulster describe the death of Ímar in 873:

Ímar, king of the Norsemen of all Ireland and Britain, ended his life.[18]

The death of Ímar is also recorded in the Fragmentary Annals of Ireland under the year 873:

The king of Lochlainn, i.e. Gothfraid, died of a sudden hideous disease. Thus it pleased God.[19]

The identification of the king of Lochlainn as Gothfraid (i.e. Ímar's father) was added by a copyist in the 17th century. In the original 11th-century manuscript the subject of the entry was simply called righ Lochlann ("the king of Lochlainn"), which more than likely referred to Ímar, whose death is not otherwise noted in the Fragmentary Annals.[20] The cause of death – a sudden and horrible disease – is not mentioned in any other source, but it raises the interesting possibility that the true provenance of Ivar's Old Norse sobriquet lay in the crippling effects of an unidentified disease that struck him down at the end of his life; though "sudden and horrible" death by any number of diseases was a common cause of mortality in the 9th century.

In 1686, a farm labourer called Thomas Walker discovered a Scandinavian burial mound at Repton in Derbyshire close to a battle site where the Great Heathen Army dispossessed the Mercian king Burgred of his kingdom. The number of partial skeletons surrounding the body, two hundred warriors and fifty women, would signify that the man buried there was of very high status, and it has been suggested that such a burial mound would be expected to be the last resting-place for a Viking of Ivar's reputation.[21]

The Saga of Ragnar Hairy Breeches says that Ivar ordered that he be buried in a place which was exposed to attack, and prophesied that, if that was done, foes coming to the land would meet with ill-success.[22] This backs up the argument that the bones found in Repton are in fact Ivar's.

Scandinavian sources

According to the saga of Ragnar Lodbrok, Ivar Boneless was the oldest son of Ragnar and Aslaug. It is said he was fair, big, strong, and one of the wisest men who had ever lived. He was consequently the advisor of his brothers Björn Ironside, Sigurd Snake-in-the-Eye, and Hvitserk.

The story has it that when king Ælla of Northumbria had murdered their father, by throwing Ragnar into a snake-pit, Ivar's brothers tried to avenge their father but were beaten. Ivar then went to king Ælla and sought reconciliation. He only asked for as much land as he could cover with an ox's hide and swore never to wage war against Ælla. Then Ivar cut the ox's hide into so fine strands that he could envelop a large fortress (in an older saga it was York and according to a younger saga it was London) which he could take as his own. (Compare the similar legendary ploy of Dido.)

Right after the messenger of king Ælla delivered the message that Ragnar had died to Ivar the Boneless, Bjorn Ironside, Sigurd Snake-eye, and Hvitserk, Ivar said: "I will not take part in or gather men for that, because Ragnar met with the fate I anticipated. His cause was bad; he had no reason to fight against King Ella, and it has often happened that when a man wanted to be overbearing and wrong others it has been the worst for him; I will take wergild from King Ella if he will give it".[23]

As Ivar was the most generous of men, he attracted a great many warriors, whom he subsequently kept from Ælla when Ælla was attacked again by Ivar's brothers. Ælla was captured, and when the brothers were to decide how to give Ælla his just punishment, Ivar suggested that they carve the "blood eagle" on his back. According to popular belief, this meant that Ælla's back was cut open, the ribs pulled from his spine, and his lungs pulled out to form "wings."

In Ragnar Lodbrok's saga, there is an interesting prequel to the Battle of Hastings: it is told that before Ivar died in England, he ordered that his body was to be buried in a mound on the English Shore, saying that so long as his bones guarded that section of the coast, no enemy could invade there successfully. This prophecy held true, says the saga, until "when Vilhjalm bastard (William the Conqueror) came ashore[,] he went [to the burial site] and broke Ivar's mound and saw that [Ivar's] body had not decayed. Then [Vilhjalm] had a large pyre made [upon which Ivar's body was] burned... Thereupon, [Vilhjalm proceeded with the landing invasion and achieved] the victory."[24]

Nickname

There is some disagreement as to the meaning of Ivar's epithet "the Boneless" (inn Beinlausi) in the sagas. Some have suggested it was a euphemism for impotence or even a snake metaphor (he had a brother named Snake-in-the-Eye). It may have referred to an incredible physical flexibility; Ivar was a renowned warrior, and perhaps this limberness gave rise to the popular notion that he was "boneless". The poem "Háttalykill inn forni" describes Ivar as being "without any bones at all".

Alternatively, the English word "bone" is cognate with the Scandinavian word "ben" and the German word "Bein", meaning "leg". Scandinavian sources mention Ivar the Boneless as being borne on a shield by his warriors. Some have speculated that this was because he could not walk and perhaps his epithet simply meant "legless"—perhaps literally or perhaps simply because he was lame. Other sources from this period, however, mention chieftains being carried on the shields of enemies after victory, not because of any infirmity.

John Haywood put forth another hypothesis from the origin of Ivar's nickname:[25] the nickname, in use by the 1140s, may be derived from a 9th-century story about a sacrilegious Viking whose bones shrivelled and caused his death after he plundered the monastery of Saint-Germain near Paris.

Genetic disease

Still another interpretation of the nickname involves Scandinavian sources as describing a condition that is sometimes understood as similar to a form of osteogenesis imperfecta. The disease is more commonly known as "brittle bone disease." In 1949, Danish researcher Knud Seedorf wrote:

Of historical personages the author knows of only one of whom we have a vague suspicion that he suffered from osteogenesis imperfecta, namely Ivar Benløs, eldest son of the Danish legendary king Regnar Lodbrog. He is reported to have had legs as soft as cartilage ('he lacked bones'), so that he was unable to walk and had to be carried about on a shield.[26]

There are less extreme forms of this disease where the person afflicted lacks the use of his or her legs but is otherwise unaffected, as may have been the case for Ivar the Boneless. In 2003 Nabil Shaban, a disability rights advocate with osteogenesis imperfecta, made the documentary The Strangest Viking for Channel 4's Secret History, in which he explored the possibility that Ivar the Boneless may have had the same condition as himself. It also demonstrated that someone with the condition was quite capable of using a longbow, such that Ivar could have taken part in battle, as Viking society would have expected a leader to do.

In popular culture

- Ivar The Boneless appears in Harry Harrison's Hammer and Cross series, which begins with the death of Ragnar and the invasion of the Heathen Army but then departs from historical events through the actions of the imaginary character Shef Sigvarthsson, who eventually defeats Ivar in single combat. Additionally, a major element of the divergence derives from a more evangelistic form of the Norse religion referred to as "The Way". Different characters offer different explanations for the appellation "the boneless"; some claim it refers to impotence, while others assert that it is because godar in shamanic trances see Ivar in the otherworld as a giant serpent.

- In the 1958 film The Vikings, Ivar has his name changed to Einar and is played by Kirk Douglas.

- In the 1989 film Erik the Viking, a character named Ivar the Boneless is portrayed by John Gordon Sinclair as a rather weedy, cowardly Viking with a high pitched voice and a tendency to get seasick.

- In The Sea of Trolls by Nancy Farmer, Ivar is a king who was formerly a famous berserker, called Ivar the Boneless only behind his back. He was called Ivar the Intrepid until he married the cruel, powerful, and beautiful shapeshifter, Frith HalfTroll.

- Ivar is a minor character in Bernard Cornwell's historical fiction novel, The Last Kingdom. The earl Ragnar the Elder explains that Ivar's sobriquet originated because he was so thin that it appeared that one could use him to string a bow. This joke might also be a play on his name, as the name Ivar is derived from yrr ar, meaning "yew warrior". (Yew was a wood commonly used for making bows.)

- In the 2013 film Hammer of the Gods Ivar the Boneless, played by Ivan Kaye, is depicted as an exiled and overweight sexual predator with an appetite for pederasty. Kaye ironically went on to play king Ælla in History Channel's Vikings.

- Ivar and his brothers are playable characters in Paradox Interactive's Crusader Kings II.

- Ivar is portrayed as the son of Ragnar and Aslaug and a younger half brother to Björn Ironside, in the History Channel television series Vikings.

- Ivar is referenced in season 3 episode 13 of Rizzoli & Isles.

- Ivar and the Great Heathen Army are referred to in The Darkness's 2015 single "Barbarian".

See also

References

- Citations

- ↑ Hervey 1907 p. 458; Harley MS 2278.

- ↑ Venning p. 132

- 1 2 Holman 2012 p. 102

- ↑ Munch pp. 245–251

- ↑ Jones pp. 218–219

- ↑ Downham 2013 p. 13

- ↑ Kirby p. 173

- 1 2 3 Forte pp. 69-70

- 1 2 Downham 2007 p. 65

- ↑ Keynes p. 526

- 1 2 Forte p. 72

- ↑ Downham 2007 p. 64

- ↑ Gransden p. 64

- 1 2 Mostert pp. 165-166

- ↑ Swanton pp. 70-71 n. 2

- ↑ Holman 2012 p. 106

- ↑ Æthelweard (1858). Giles Tr., J.A, ed. Six Old English Chronicles: Æthelweard's Chronicle. London: Henry G. Bohn. Bk. 4. Ch 2

- ↑ Annals of Ulster, s.a. 873

- ↑ "Fragmentary Annals of Ireland 409". CELT. Retrieved 2 February 2009.

- ↑ John O'Donovan, who edited and translated the Fragmentary Annals in 1860, understood the entry to refer to Ímar. Earlier in the same annals, Ímar and his brother Amlaíb are call na righ Lochlann, or "the kings of Lochlainn" (FA 388). See also Donnchadh Ó Corráin, The Vikings in Scotland and Ireland in the Ninth Century §40 for further discussion.

- ↑ "The Vikings: A Short History", Martin Arnold, author; The History Press: Stroud, 2008, Introduction , "The Death of Ivar the Boneless & Viking Age History", pp. 9–21.

- ↑ The Vikings: Culture and Conquest

- ↑ The Viking Age

- ↑ Donovan pp. 44–45; 145, 148.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of the Vikings

- ↑ Seedorf, Knud. Osteogenesis imperfecta: A study of clinical features and heredity based on 55 Danish families, 1949.

- Bibliography

- Haywood, John (1 January 2015). Encyclopedia of the Vikings. Thames & Hudson Inc.

- "The Annals of Ulster". Corpus of Electronic Texts (15 August 2012 ed.). University College Cork. 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- Ashley, Mike (7 June 2012). The Mammoth Book of British Kings and Queens. Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 978-1-4721-0113-6.

- Donovan, Frank R. (1965). The Vikings: In Consultation with Thomas D.Kendrick. Cassell (pr.Verona).

- Downham, Clare (2007). Viking Kings of Britain and Ireland: The Dynasty of Ívarr to A.D. 1014. Dunedin Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-9037-6589-0.

- Downham, Clare (2013). "Annals, Armies, and Artistry: 'The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle', 865–96". No Horns on their Helmets? Essays on the Insular Viking-age. Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, and Scandinavian Studies (series vol. 1). The Centre for Anglo-Saxon Studies and The Centre for Celtic Studies, University of Aberdeen. pp. 9–37. ISBN 978-0-9557720-1-6. ISSN 2051-6509.

- Forte, A; Oram, RD; Pedersen, F (2005). Viking Empires. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82992-2.

- Gransden, A (2000) [1996]. Historical Writing in England. Vol. 1, c. 500 to c. 1307. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-15124-4.

- "Harley MS 2278". British Library. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- Hervey, F, ed. (1907). Corolla Sancti Eadmundi: The Garland of Saint Edmund King and Martyr. London: John Murray. Accessed via Internet Archive.

- Holman, Katherine (July 2003). Historical dictionary of the Vikings. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-4859-7.

- Holman, Katherine (26 April 2012). The Northern Conquest: Vikings in Britain and Ireland. Andrews UK Limited. ISBN 978-1-908493-53-8.

- Jones, Gwyn (1984). A History of the Vikings. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-215882-1.

- Keynes, S (2014). "Appendix I: Rulers of the English, c.450–1066". In Lapidge, M; Blair, J; Keynes, S; Scragg, D. The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England (2nd ed.). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 521–538. ISBN 978-0-470-65632-7.

- Kirby, D. P. (2000). The Earliest English Kings. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-24211-0.

- Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (2 October 2013). The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-31609-2.

- "Laud MS Misc. 636". Bodleian Library. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- Malam, John (6 February 2012). Yorkshire, A Very Peculiar History. Andrews UK Limited. ISBN 978-1-908759-50-4.

- Mostert, M (1987). The Political Theology of Abbo of Fleury: A Study of the Ideas about Society and Law of the Tenth-century Monastic Reform Movement. Middeleeuwse studies en bronnen (series vol. 2). Hilversum: Uitgeverij Verloren. ISBN 90-6550-209-2.

- Munch, Peter Andreas (1926). Norse Mythology: Legends of Gods and Heroes. The American-Scandinavian Foundation.

- Swanton, M, ed. (1998) [1996]. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-92129-5.

- Venning, Timothy (30 January 2014). The Kings & Queens of Anglo-Saxon England. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4456-2459-4.

External links

- CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts at University College Cork. The Corpus of Electronic Texts includes the Annals of Ulster and the Four Masters, the Chronicon Scotorum and the Book of Leinster as well as Genealogies, and various Saints' Lives. Most are translated into English, or translations are in progress.

External links

- Ivar 1 at Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England

- The History Files: In the Footsteps of Ivarr the Boneless

- A site on the disease Osteogenesis Imperfecta

- Northvegr – The Tale of Ragnar's Sons

- Nabil Shaban's page about Ivar the Boneless

- An article discussing the OI theory

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||