Italian war crimes

Italian war crimes have been associated mainly with Fascist Italy in the Second Italo-Ethiopian War and World War II.

Pacification of Libya

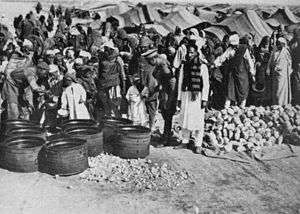

In 1923, Mussolini embarked upon a campaign to consolidate control over the Italian territory of Libya and Italian forces began occupying large areas of Libya to allow for rapid settlement by Italian colonists. They were met with resistance from the Senussi led by Omar Mukhtar. Civilians suspected of collaboration with the Senussi were executed in large numbers. Refugees from the fighting were subject to bombing and strafing by Italian aircraft. In 1930, in northern Cyrenaica 100,000 Bedouins were expelled and their land given to Italian settlers, which has been called an act of ethnic cleansing. The Bedouins were forced to march across the desert into concentration camps. Starvation and other poor conditions in the camps were rampant and the internees were used for forced labour, ultimately leading to the deaths of nearly 40,000 internees by the time they were closed in September 1933.[1]

Second Italo-Ethiopian War

During the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, Italian violations of the laws of war were reported and documented.[2] These included use of chemical weapons such as mustard gas and attacks on Red Cross facilities.

During the 1936–1941 Italian occupation, atrocities also occurred; in the February 1937 Yekatit 12 massacres as many as 30,000 Ethiopians may have been killed and many more imprisoned as a reprisal for the attempted assassination of Viceroy Rodolfo Graziani. Thousands of Ethiopians also died in concentration camps such as Danane and Nocra.

World War II

The British and American governments, fearful of post-war Italian Communist Party, effectively undermined the quest for justice by tolerating Italy's efforts made by its top authorities to avoid any of the alleged war criminals to be extradited and taken to court.[3][4] Fillipo Focardi, a historian at Rome's German Historical Institute, has discovered archived documents showing how Italian civil servants were told to avoid extraditions. A typical instruction was issued by the Italian prime minister, Alcide De Gasperi, reading: "Try to gain time, avoid answering requests."[3] The denial of Italian war crimes was backed up by the Italian state, academe, and media, re-inventing Italy as only a victim of the German Nazism and the post-war Foibe massacres.[3]

A number of suspects, known to be on the list of Italian war criminals that Yugoslavia, Greece and Ethiopia requested an extradition of, at the end of the World War II never saw anything like Nuremberg trial, because the British government with the beginning of the Cold War saw in Pietro Badoglio, who was also on the list, a guarantee of an anti-communist post-war Italy.[3][4][5][6]

Documents found in British archives by the British historian Effie Pedaliu[4] and in Italian archives by the Italian historian Davide Conti,[7] pointed out that the memory of the existence of the Italian concentration camps and Spanish war crimes had been repressed due to the Cold War. The Province of Ljubljana saw the deportation of 250,000 people, which equaled 7.5% of the total population. The operation, one of the most drastic in Europe, filled up many Italian concentration camps, such as Rab, Gonars, Monigo, Renicci di Anghiari and elsewhere. The survivors received no compensation from the Italian state after the war. In early July 1942, Italian troops operating opposite Fiume, were reported to have shot and killed 800 Croat and Slovene civilians and burned down 20 houses near Split on the Dalmatian coast.[8] Later that month, the Italian Air Force was reported to have practically destroyed four Yugoslav villages and killed hundreds of civilians in revenge for a local guerrilla attack that resulted in the death of two high-ranking officers.[9] In the second week of August 1942, Italians troops were reported to have burned down six Croatian villages and shot dead more than 200 civilians in retaliation for guerrilla attacks.[10] During September 1942, the Italian Army was reported to have destroyed 100 villages in Slovenia and killed 7,000 villagers in reprisal against local guerrilla attacks.[11]

A similar phenomenon took place in Greece in the immediate postwar years. The Italian occupation of Greece was often brutal, resulting in reprisals such as the Domenikon Massacre.[12] After two Italian filmmakers were jailed in the 1950s for depicting the Italian invasion of Greece and the subsequent occupation as a "soft war", the Italian public and media were forced into the repression of collective memory, which led to historical amnesia and eventually to historical revisionism,[13]

The repression of memory led to historical revisionism[13] in Italy and in 2003 the Italian media published Silvio Berlusconi's statement that Benito Mussolini only "used to send people on vacation".[14][15]

List of Italian war criminals

This is a working list of Italian high-ranking military personnel or other officials involved in acts of war. It includes also such personnel of lower rank that were accused of grave breaches of the laws of war. Inclusion of a person does not imply that the person was qualified as a war criminal by a court of justice. As noted in the relevant section, very few cases have been brought to court due to diplomatic activities of, notably, the government of the United Kingdom and subsequent general abolition.

The criterion for inclusion in the list is existence of reliable documented sources.

- Benito Mussolini: In 1936, during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, Mussolini ordered the manufacturing/purchase of hundreds of tons of yperite, phosgene and fire munitions in the form of aerial bombs and artillery and mortar shells.

- Pietro Badoglio: In 1936, during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, Badoglio approved, as commander in chief of the Italian army, the use of poisonous gas against enemy troops.

- Rodolfo Graziani: In 1950, a military tribunal sentenced Graziani to prison for a term of 19 years (but released after a few months) as punishment for his collaboration with the Nazis, when he was Minister of Defense of the Italian Social Republic.

- Mario Roatta: In 1941–1943, during the 22-month existence of the Province of Ljubljana, Roatta ordered the deportation of 25,000 people, which equaled 7.5% of the total population. The operation, one of the most drastic in Europe, filled up Italian concentration camps on the island of Rab, in Gonars, Monigo (Treviso), Renicci d'Anghiari, Chiesanuova and elsewhere. The survivors received no compensation from the Italian state after the war. He had, as the commander of the 2nd Italian Army in Province of Ljubljana, ordered besides internments also summary executions, hostage-taking, and burning of houses and villages,[16][17] for which after the war the Yugoslav government sought unsuccessfully to have him extradited for war crimes. He was quoted as saying "Non dente per dente, ma testa per dente" ("Not a tooth for tooth but a head for a tooth"), while Robotti was quoted as saying "Non si ammazza abbastanza!" ("There are not enough killings") in 1942.[18] "On 1 March 1942, he (Roatta) circulated a pamphlet entitled '3C' among his commanders that spelled out military reform and draconian measures to intimidate the Slav populations into silence by means of summary executions, hostage-taking, reprisals, internments and the burning of houses and villages. By his reckoning, military necessity knew no choice, and law required only lip service. Roatta's merciless suppression of partisan insurgency was not mitigated by his having saved the lives of both Serbs and Jews from the persecution of Italy's allies Germany and Croatia. Under his watch, the 2nd Army's record of violence against the Yugoslav population easily matched the German. Tantamount to a declaration of war on civilians, Roatta's '3C' pamphlet involved him in war crimes."[17] One of Roatta's soldiers wrote home on July 1, 1942: "We have destroyed everything from top to bottom without sparing the innocent. We kill entire families every night, beating them to death or shooting them."[19] As noted by Minister of Foreign Affairs in Mussolini government, Galeazzo Ciano, when describing a meeting with secretary general of the Fascist party who wanted Italian army to kill all the Slovenes:

(...) I took the liberty of saying they (the Slovenes) totaled one million. It doesn't matter – he replied firmly – we should model ourselves upon ascari (auxiliary Eritrean troops infamous for their cruelty) and wipe them out".[20]

- Mario Robotti, Commander of the Italian 11th Division in Slovenia and Croatia, issued an order in line with a directive received from Mussolini in June 1942: "I would not be opposed to all (sic) Slovenes being imprisoned and replaced by Italians. In other words, we should take steps to ensure that political and ethnic frontiers coincide.",[21] which qualifies as ethnic cleansing policy.

- Nicola Bellomo was an Italian general who was tried and found guilty for killing a British prisoner of war and wounding another in 1941. He was one of the few Italians to be executed for war crimes by the Allies, and the only one executed by a British-controlled court.

- Pietro Caruso was chief of the Fascist police in Rome while it was occupied by the Germans. He helped organize the Ardeatine massacre in March 1944. After Rome was liberated by the Allies he was tried that September and subsequently executed by the co-belligerent Italian government.

- Guido Buffarini Guidi was the Minister of the Interior for the Italian Social Republic; shortly after the end of the war in Europe he was found guilty of war crimes and executed by the co-belligerent government.

- Pietro Koch was head of the Banda Koch, a special task force of the Corpo di Polizia Repubblicana dedicated to hunting down partisans and rounding up deportees. His ruthless extremism was cause for concern even to his fellow fascists, who had him arrested in October 1944. When he came into Allied captivity he was convicted of war crimes and executed.

See also

- Italian Fascism

- Italian Fascism and racism

- Anti-Italianism

- Internment of Italian Americans

- Italian Civil War

References

- ↑ Duggan, Christopher (2007). The Force of Destiny: A History of Italy Since 1796. New York: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 496–497.

- ↑ Effie G. H. Pedaliu (2004) Britain and the 'Hand-over' of Italian War Criminals to Yugoslavia, 1945–48. Journal of Contemporary History. Vol. 39, No. 4, Special Issue: Collective Memory, pp. 503–529 (JStor.org preview)

- 1 2 3 4 Italy's bloody secret (Archived by WebCite®), written by Rory Carroll, Education, The Guardian, June 2001

- 1 2 3 Effie Pedaliu (2004) Britain and the 'Hand-over' of Italian War Criminals to Yugoslavia, 1945–48. Journal of Contemporary History. Vol. 39, No. 4, Special Issue: Collective Memory, pp. 503–529 (JStor.org preview)

- ↑ Oliva, Gianni (2006) «Si ammazza troppo poco». I crimini di guerra italiani. 1940–43, Mondadori, ISBN 88-04-55129-1

- ↑ Baldissara, Luca & Pezzino, Paolo (2004). Crimini e memorie di guerra: violenze contro le popolazioni e politiche del ricordo, L'Ancora del Mediterraneo. ISBN 978-88-8325-135-1

- ↑ Conti, Davide (2011). "Criminali di guerra Italiani". Odradek Edizioni. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ↑ Report Italians Execute 800 in Yugoslavia

- ↑ Italians Level Slav Villages In Reprisal

- ↑ ITALIANS BURN 6 CROAT TOWNS

- ↑ Italians Raze 100 Sloven Villages

- ↑ P. Fonzi, “Liquidare e dimenticare il passato”: i rapporti italo – greci tra il 1943 e il 1948, in “Italia Contemporanea”, 266 (2012), pp. 7–42

- 1 2 Alessandra Kersevan 2008: (Editor) Foibe – Revisionismo di stato e amnesie della repubblica. Kappa Vu. Udine.

- ↑ Survivors of war camp lament Italy's amnesia, 2003, International Herald Tribune

- ↑ Di Sante, Costantino (2005) Italiani senza onore: I crimini in Jugoslavia e i processi negati (1941–1951), Ombre Corte, Milano. (Archived by WebCite®)

- ↑ Giuseppe Piemontese (1946).Twenty-nine months of Italian occupation of the Province of Ljubljana, page 10.

- 1 2 James H. Burgwyn (2004). General Roatta's war against the partisans in Yugoslavia: 1942, Journal of Modern Italian Studies, Volume 9, Number 3, pp. 314–329(16)

- ↑ Gianni, Oliva (2007) "Si ammazza troppo poco". I crimini di guerra italiani 1940–1943, Mondadori.

- ↑ James Walston, a historian at The American University of Rome. Quoted in Rory, Carroll. Italy's bloody secret. The Guardian. (Archived by WebCite®), The Guardian, London, UK, June 25, 2003

- ↑ The Ciano Diaries 1939–1943: The Complete, Unabridged Diaries of Count Galeazzo Ciano, Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs, 1936–1943 (2000) ISBN 1-931313-74-1

- ↑ Tommaso Di Francesco, Giacomo Scotti (1999) Sixty years of ethnic cleansing, Le Monde Diplomatique, May Issue.

Sources

- Giuseppe Piemontese (1946): Twenty-nine months of Italian occupation of the Province of Ljubljana

- Lidia Santarelli: "Muted violence: Italian war crimes in occupied Greece", Journal of Modern Italian Studies, September 2004, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 280–299(20); Routledge, part of the Taylor & Francis Group

- Effie Pedaliu (2004): Britain and the ‘Hand-Over’ of Italian War Criminals to Yugoslavia, 1945–48, Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 39, No. 4, 503–529 (JStor.org preview)

- Pietro Brignoli (1973): Santa messa per i miei fucilati, Longanesi & C., Milano,

- H. James Burgwyn (2004): "General Roatta's war against the partisans in Yugoslavia: 1942", Journal of Modern Italian Studies, September vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 314–329(16)

- Gianni Oliva (2006): 'Si ammazza troppo poco'. I crimini di guerra italiani 1940–43. ('There are too few killings'. Italian war crimes 1940–43), Mondadori, ISBN 88-04-55129-1

- Alessandra Kersevan (2003): "Un campo di concentramento fascista. Gonars 1942–1943", Comune di Gonars e Ed. Kappa Vu,

- Alessandra Kersevan (2008): Lager italiani. Pulizia etnica e campi di concentramento fascisti per civili jugoslavi 1941–1943. Editore Nutrimenti,

- Alessandra Kersevan 2008: (Editor) Foibe – Revisionismo di stato e amnesie della repubblica. Kappa Vu. Udine.

- Luca Baldissara, Paolo Pezzino (2004). Crimini e memorie di guerra: violenze contro le popolazioni e politiche del ricordo. ISBN 978-88-8325-135-1

- Italian Crimes In Yugoslavia (Yugoslav Information Office – London 1945)

- Mass internment of civil population under inhuman conditions – Italian concentration camps